How to build up a negative narrative without any basis? Here is a small illustration. Media reports like this one said Diwali 2015 was responsible for the sharp deterioration of air quality in Delhi. What was not highlighted was the fact that Delhi’s air quality had dropped to alarming levels by the week preceding Diwali. This pattern is repeated in 2016. What, then, was to actually blame for this precipitous fall? The annual pre-winter burning of farm stubble in adjacent states. Indeed, air quality improved slightly immediately after Diwali 2016.

For the lazy, perhaps the easiest way to pose as rational is by attacking Hindu traditions. So, ever since a Supreme Court bench ordered an utterly misguided ban on the sale of firecrackers for this Diwali, the blame for pollution has been unequivocally pinned on Diwali, without the slightest evidence, even as everyone agrees the problem is spread over two-three months. The Court itself admitted there was no scientific evidence to suggest firecrackers were augmenting already prevailing levels of pollution (see para 69 of its judgement dated 12.09.2017).

Through nothing but false arguments buttressed by shrill propaganda, Diwali celebrations have been made synonymous with pollution. It is time to bring such pseudoscientific arguments under the scanner, especially as they have been made at the highest quarters of decision-making.

No, Minister

Union Minister for Science and Technology, Environment, and Climate Change, Dr. Harsh Vardhan tweeted (only to delete his tweet later) that he welcomed the cracker ban in Delhi, as he believed it would help reduce pollution. One doesn’t need to be a rocket scientist to mentally picture that the result of one day’s worth of crackers is not in the same ballpark as that of burning agricultural waste from lakhs of acres of farms.

Successive governments have not initiated any steps to curtail the open burning of farm waste (which, by the way, has just started again), and encourage instead the production of biochar from this waste, which is known to be an effective carbon sequestration strategy. It has been known for centuries that adding biochar to the soil may improve fertility dramatically. Yet, the temptation to do the lazy thing of blaming Diwali crackers has proved irresistible, when what is really needed is to provide farmers with pyrolysis furnaces on a war footing. Another acknowledged contributor is dust from construction sites. It is these sources the Supreme Court should be concerned with if it is genuinely bothered about the declining quality of air. Which brings us to a very disturbing conclusion: elected governments have passed the buck to an unaccountable judiciary, which is resorting to knee-jerk reactions. The resulting farce is far-reaching decision-making based on pseudoscience, informed, as it were, by WhatsApp forwards. And the tragic destruction of a great tradition.

Science vs. Pseudoscience: no spike in pollution on Diwali

The rationale behind the SC’s decision to extend the ban on cracker sale is to observe what the impact on pollution would be. Sadly, sufficient thought does not appear to have gone into a decision that causes huge monetary losses to lakhs of people, and severs many more lakhs from their ancient tradition.

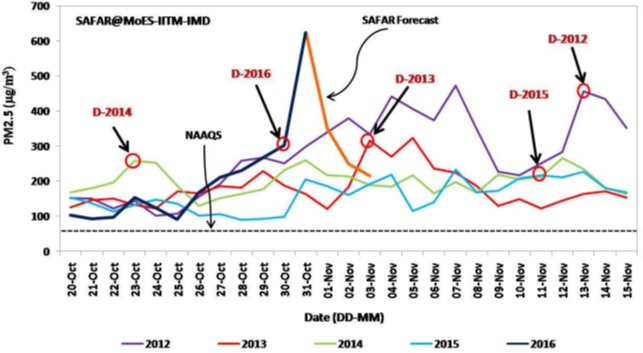

Diwali pollution levels in the three years from 2012 to 2015 have been equaled or slightly exceeded either before or later during the mid-October to mid-November period, as can be seen from Figure 1, which shows the levels of the most dangerous particulates smaller than 2.5 micrometres (PM2.5). (At this point, it is advisable to see what exactly comprises these particulates, and why they are so especially closely followed – see here.) This implies the pollution load from Diwali is negligible – the data for 2015 makes this especially clear – and there are other actual contributing factors at play, which are being ignored by sensational media reports. Whether one likes it or not, that’s what the hard data says.

Figure 1. Atmospheric concentration of particulates smaller than 2.5 micrometres (PM2.5) in Delhi for the period 20th October to 15th November for four years (2012-2016, 2016 incomplete), obtained from SAFAR-India.

The day after Diwali 2016 (31st October) sees a rather high level of particulates, but environmental scientists pointed out this was an anomaly caused by extraneous factors like especially low winds and atmospheric boundary layer conditions, which meant that regular dispersal by winds wasn’t happening. There was an avalanche of articles in the media screaming Diwali 2016 had caused the “worst air conditions in a decade”, which sidestepped this fact. The propaganda was successful: from that time on, Diwali fireworks were instruments of genocide. It didn’t matter that, after a brief recovery on 1-2 November 2016, the smog worsened considerably later, with particulate levels dwarfing that on Diwali, again highlighting the fact that the real contributors to pollution were being ignored in the haste to sensationalise.

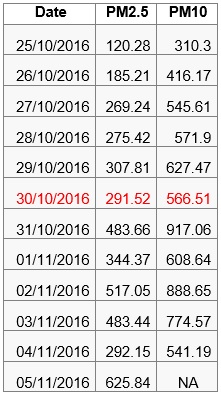

Consider the actual PM2.5 and PM10 data for RK Puram (data for other stations is very similar) for the period 25th October to 5th November, 2016, in the Table. The levels on the 29th, a day before Diwali, are actually higher than that on Diwali. So what was responsible for this? And by 5th November, the PM2.5 has climbed to more than twice that on Diwali. What, then, was the logic in blaming Diwali for the smog?

Table: PM2.5 and PM10 levels (in µg/m3) for RK Puram, Delhi obtained from CPCB. The acceptable standards are 60 and 100 µg/m3, respectively.

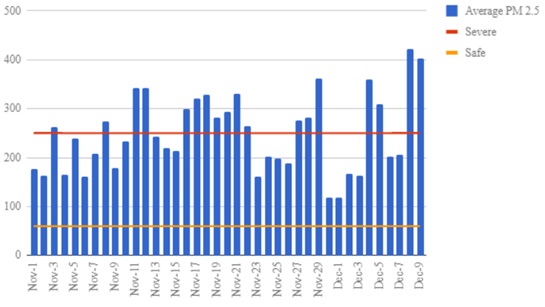

Previously too, data for the period after Diwali 2014 (Figure 2) clearly shows that the level of particulates in Delhi’s air climb increasingly higher than the Diwali level (and well past the Severe mark) as the winter advances. Tellingly, it was further observed that the highest particulate levels of the day are recorded late at night or early in the mornings. What does this mean? The particulates are probably from open wood or other biofuel (dung, sawdust etc.) fires, lit by people for warmth.

Figure 2. PM2.5 levels in Delhi for a period of forty days after Diwali 2014 (obtained from this report in The Hindu

This only reinforces what has been known for long: in India, burning of wood or other biomass (like farm waste, forests etc.) is a major contributor to particulate emissions, responsible for as much as half, whereas the remainder comes from burning fossil fuels (such as petrol and kerosene). This is in contrast to the situation in the west from after the Industrial Revolution, where the contribution of biomass to particulates emissions has been minor.

It should be obvious that, to blame Diwali crackers for increasing particulates in the atmosphere, while ignoring the fires raging over lakhs of hectares of farms, or the widespread use of wood fires for purposes such as cooking and keeping warm, as our lazy rationalists are doing, is incredibly silly. And yet, this is no problem to be trivialized by such pseudoscientific hogwash: the particulates are probably causing faster melting of the Himalayan ice caps. For India’s sake, I earnestly hope decision-makers wake up to reality.

The SC ban on cracker sales is alarming for another reason. Can an activist and over-reaching judiciary that takes arbitrary decisions, which fly in the face of scientific evidence and reasoning, inspire confidence that it can deal with complex scientific and ethical issues that may arise from research and innovation in the future? Would innovation-driven companies be keen on setting up shop in a country with such a judiciary?

When refusing to relax the ban on 10th October, the SC further observed that there was a “direct connection” between Diwali fireworks and deteriorating air quality. This seems to contradict the SC’s own judgment of 12th September mentioned above, while offering no new evidence for this fresh claim. Not only is such inconsistency embarrassing, but it also shows a judiciary that seems to have also fallen for the temptation to find a whipping boy.

Let us now look at some subtler issues that the cracker ban may have overlooked, and how it may be hastily doing away with a tradition that may have a very sound scientific basis.

Diwali: where science meets fun

Those who welcomed the Supreme Court’s misguided ban on the sale of crackers ahead of Diwali, have advanced the sophism that Diwali is all about lighting lamps, and not at all about fireworks and crackers. But lighting lots of lamps is not unique to Diwali day by any stretch of imagination. What about things like Laksha Deeparchana on Mahashivratri? In fact, traditionally, starting with Diwali, lamps are supposed to be lit daily right through the month of Kartika, although we nowadays make do with just a couple of lamps at the threshold of homes for convenience.

The idea of sound as a means of celebration is intuitive, and perhaps no-one knows this better than the Indians; I don’t know how many cultures have an equivalent expression for band-baajaa. So, if neither sound nor light is a unique to any celebration in India, how did the practice of community-wide bursting of fireworks and crackers on Diwali come about? This is even more significant when we consider that India does not have decent resources of sulphur, a vital ingredient of traditional fireworks and explosives, which stymied the development of India’s military technology and left it at an inexorable disadvantage vis-à-vis foreign invaders for centuries.

Sulphur, the key ingredient

Indians, nevertheless, were always aware of the uses of sulphur, which is an ingredient in many Ayurvedic formulations. And fumigation by burning sulphur was widely employed for pest control, giving sulphur its Sanskrit name, gandhaka, owing to the acrid smell of the gaseous sulphur oxides produced by its combustion, even though sulphur itself is odourless. That it was not named after its striking appearance – bright yellow powder – but for its combustion properties attests that it was highly valued as a fumigant. The name “sulphur” itself is derived from the Sanskrit, śulvāri, which means, “to burn”. The use of sulphur and sulphur compounds for fumigation (dhoopana dravya) is clearly documented in Ayurvedic texts. Owing to unavailability in elemental form in India, sulphur had to be indirectly extracted from pyrites, suggesting its use in fireworks was calculated. Those who ask why fireworks are not mentioned in any scriptures, or claim that they are an “unholy add-on” should ponder this point.

Another commonly used ingredient in crackers and fireworks are phosphorus compounds (the safety matches we use contain red phosphorus, which is responsible for the pungent smell when a match is lit), the products of combustion of which have a similar effect. Metal shavings – predominantly the non-toxic iron, aluminium and magnesium – are responsible for colourful sparks.

Many articles raise the spectre of heavy metal pollution (like antimony, strontium, lead etc.) from Diwali fireworks, but this is either silly or irresponsible scare-mongering: unlike the west or China, Indian fireworks makers simply do not use these chemicals as they are just too costly! Indeed, perchlorate usage too is very low, for exactly the same reason. In my childhood, many families would come together to make firecrackers for Diwali. We would make a wide range of fireworks simply by varying the proportions and permutations of the basic traditional ingredients. I therefore find it slightly amusing when commentators try to extrapolate pollution analyses from 4th of July pyrotechnics to Diwali, without checking if they are relevant.

Diwali can be thought of as a timed release of pesticidal fumes after the monsoon, when many insects and germs breed (yes, this is why so many people go down with a variety of fevers and infections, if not worse, around this time) for ensuring public health, and crucially, ahead of the sowing season commencing in November, to ensure crop safety.

Sulphur dioxide disinfection vs. modern alternatives

The SC judgement said, “Sulphur on combustion produces sulphur-dioxide and the same is extremely harmful to health. The CPCB has stated that between 9 p.m. to midnight on Deepavali day, the levels of sulphur-dioxide content in the air is dangerously high.” No figures were quoted. Indeed, the detailed sulphur dioxide data I could download for multiple recording stations in Delhi for Diwali 2016 from the CPCB website itself came with the CPCB’s assessment that the levels did not exceed the prescribed standard! And no-one seems to have told the bench about the medically acknowledged disinfectant value of sulphur dioxide, or that it has been used for this purpose for ages.

Fumigation – even that with synthetic pesticides – relies on achieving a high concentration of the active chemical to neutralize germs and pests. I don’t know if this is still done, but typically, on Diwali, the first few fireworks are lit within homes (with the sparks falling into a vessel of water) for fumigation, before the revelry moves outdoors. And it turns out, sulphur dioxide is a particularly effective disinfectant, as this article by a former Chief Inspector of the New York City Health Department says. Closer to home, doctors have credited Diwali smoke with causing a decline in the incidence of dengue. The sulphurous fumes generated in Diwali are deliberate – they may cause a few tears (such chemicals are called lachrymatory agents, such as that released when onions are cut), but a momentary spike will cause no lasting damage.

Simultaneously, doctors have also raised questions about the efficacy of fogging, which is done around the same time, pointing out that insects have become immune to the chemicals being used, which, ironically, are nevertheless extremely hazardous for humans. There was a recent tragic report that twenty people had died, many were left blinded and hundreds were hospitalized owing to exposure to insecticides being sprayed in fields in Maharashtra. And what about the fact that the insecticides will have similar effects on birds and animals? No-one is concerned that we are releasing tonnes of such insecticides annually into the open environment. Worse still, they are entering our bodies through food – again, no-one is bothered, even after the shocking death of school children from eating a mid-day meal contaminated with insecticide in Bihar in 2013. Toxic pesticide residues have been detected in human breast milk in Bhopal!

It is sheer madness to persist with the widespread use of such chemicals, but we do it nonchalantly. And to do away with practices and traditions which provide natural and safe alternatives is to compound the madness. As toxic chemicals go, sulphur dioxide is relatively harmless to humans, and would require unusually high levels of exposure to cause lasting damage. One unbeatable advantage sulphur dioxide has over insecticides is that it is soluble in water, and is easily scrubbed from the environment within a few hours of release (a fact confirmed by the CPCB data), or our bodies within minutes.

Hasty decisions like the cracker ban also have alarming implications for a country like India that has a great deal of traditional knowledge in everyday use.

It would have been quite another matter if regulatory attempts had focused on specific chemicals in fireworks – especially Chinese ones – but that kind of scientific depth has so far been altogether missing.

‘Noise pollution’

There is a difference between the loudest sound produced by beating dhols or playing shehnais, and that from an exploding cracker: explosions produced by sudden production of large volumes of gaseous products from tiny amounts of solids give rise to shockwaves. Nevertheless, the explosive charges in commonly available crackers are not capable of causing lasting damage to animals and birds. (Very loud crackers should indeed be banned.) But what the shockwaves produced by crackers can do is to break the calcareous shells of insect eggs, and the cuticles of larvae. That takes care of pests that cannot be neutralized by simple fumigation. This explains the design behind bursting crackers for Diwali, when other festive occasions generally get no more than a lot of dhol-beating. Does this sound far-fetched? Not really: a heap of phosphorus can explode by simple impact, so the effect of such an accidental explosion on eggs could easily have been observed!

Pushing for a blanket-ban on crackers on Diwali is misplaced: if one day of crackers constitutes unacceptable levels of noise pollution, then, by the same argument, no construction should be allowed near inhabited areas, and pneumatic drills should be banned outright.

Cigarette smoke: a major pollutant in ways you don’t suspect

Evidence has been around for some time now that cigarettes pose a much bigger danger than acknowledged sources of pollution. Three cigarettes produce around ten times more particulates than a diesel vehicle idling for a half-hour. Worse still, it was reported in 1978 that cigarette smoke makes the impact of other pollutants deadlier – to quote the abstract of the report, “…total pollutant burden is increased, there is cumulative irritation of the airways, pollutants are deposited selectively in the airways [upon recent exposure to cigarette smoke]”.

Over 30% of Delhi’s men smoke. Wouldn’t it be more rational to progressively reduce the supply of cigarettes and beedis, and declare at least a few days a year as no-smoking days? A simple mental calculation suggests a 5% reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked daily would be equivalent to taking thousands of vehicles off the road for an hour every day.

Tobacco plants imbibe unusually large amounts of many heavy metals as micronutrients from the soil. Consequently, cigarette smoke is a major source of toxic heavy metals like chromium, cadmium, lead and nickel for smokers as well as passive smokers, that too in a form that can easily enter the human body.

It is astonishing how a thoroughly negative narrative has been built up around Diwali celebrations. Yet, claims that firecrackers are a source of pollution are pseudoscientific, and simply do not stand up to scrutiny. We are bothered by the relatively miniscule amounts of perchlorate from one day’s worth of Diwali crackers, but ignore the large amounts of it entering the environment or our bodies directly through fertilizers. The small amounts of metal shavings in crackers are a concern, but the enormous amounts of heavy metals given out daily in cigarette smoke and going straight into our lungs merit no action!

Diwali celebrations are a fun way of carrying out communal fumigation, in order to ensure public health after the monsoons, with virtually no negative fallout. Given the hard data at hand, one might venture so far as to suggest that it was truly silly to even drag the question of whether Diwali celebrations can take place as usual, to a court of law. But then, we live in interesting times, and can only hope that, after all the farce, solid good sense prevails in the end. Lazy, cosmetic steps won’t do: if at all, the bull must be taken by the horns.

Featured Image: https://cashkaro.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Anil Suri has a PhD in chemistry from Durham University, UK. He is a materials scientist based in Aalborg, Denmark, whose research interests lie in carbon nanotubes and graphene. He occasionally writes on Indian history and culture, especially aspects that involve science.