Devdutt Pattkanaik is one of India’s bestselling authors on Hinduism today. He has a breezy, eay-to-read style, packaged for consumption by today’s urban Hindu who may have little time to delve deeper into his or her faith. The vast corpus of primary texts on Hinduism does not make the job any easier.

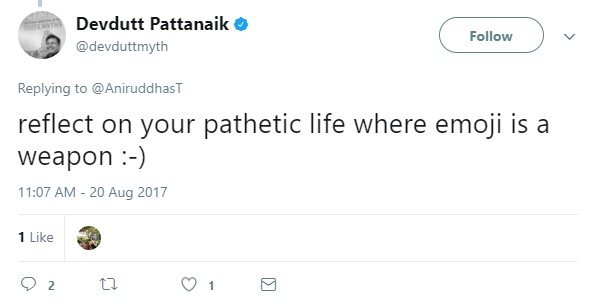

His writings, however, have shown a persistent tendency to distort, misrepresent, and fabricate. His outbursts on social media paint a picture of a man driven by psychological problems, prone to hurling abuses when questioned and a remarkable inability to respond to valid criticisms. I have covered this in the last section of this article.

In 2017 I had the opportunity to purchase and read a book – “The Illustrated Mahabharata”, published by DK Books. The book is a lavishly produced coffee-table book that not only presents the story of the epic in summarized form – sourced from Devdutt’s book, “Jaya”, but also has selected verses from Bibek Debroy’s translation of the Critical Edition of the Mahabharata. In addition, there are photographs galore in the book. Going through this excellently produced book, my attention was drawn to one, then two, and then innumerable errors, distortions, misrepresentations of the Mahabharata itself. The passages bore a strong resemblance to Devdutt’s “Jaya”, which in itself was not surprising, since the editors make it clear they used his book.

I wrote a blog post on some of the errors I found. This post is an expanded version of that blog post. I have first reproduced the relevant excerpt from the book, and then compared it with what is in the Critical Edition (Bibek Debroy’s unabridged English translation of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute’s Critical Edition of the Mahabharata, published by Penguin from 2010-2014), and then with the Gita Press’s Hindi translation of the complete Mahabharata.

1. GANDHARI’S PREGNANCY

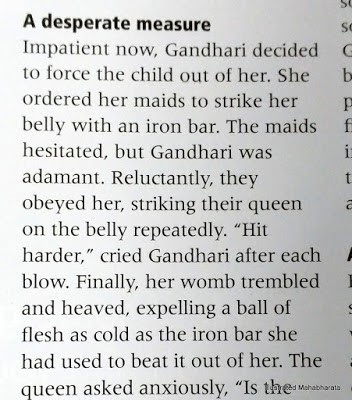

What Devdutt writes – “Impatient now, Gandhari decided to force the child out of her. She ordered her maids to strike her belly with an iron bar….”

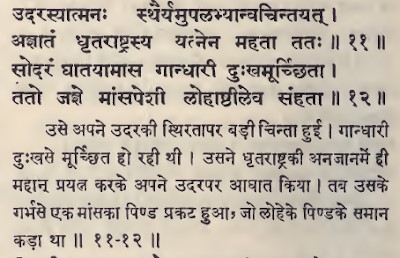

What the Critical Edition says – “Unknown to Dhritarashtra, Gandhari violently struck her belly and aborted herself, fainting with the pain. A hard mass of flesh, like an iron ball, came out.” [Unabridged Mahabharata, Adi Parva, Ch. 107]

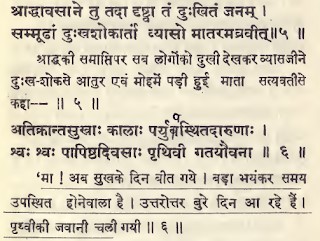

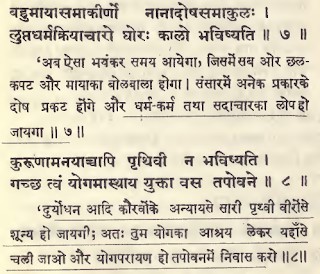

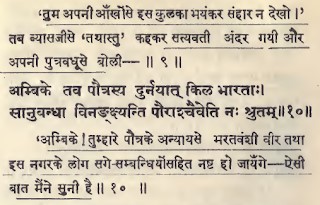

What the Gita Press says – it is more or less consistent with the Critical Edition (see the screenshot below).

Devdutt is wrong in writing that Gandhari ordered the maids to strike her belly. Neither the Critical Edition nor the Gita Press make any mention of such an act. He is then also obviously wrong when he writes that Gandhari ordered the maids to do so “repeatedly.”

What was a tragic act of self-abortion by Gandhari, taken in the heat of the moment, Devdutt turns into a wanton, deliberate act of murder in which her maids participate.

2. SATYAVATI’S DEPARTURE

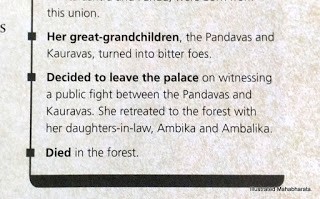

What Devdutt writes – Satyavati “decided to leave the palace on witnessing a public fight between the Pandavas and Kauravas.“

What the Critical Edition says – After Pandu’s death and last rites, it was Vyasa who told Satyavati that hard times were ahead, and advised her to “give everything up and live in a hermitage. You will not be able to witness the destruction of your sons and lineage.” [Adi Parva, Ch 119]

What the Gita Press says -is in line with what the Critical Edition says. See the three screenshots below from Ch 127 of the Adi Parva.

Firstly, there is no mention of a “public fight” between the Kauravas and Pandavas that precipitated Satyavati’s departure. Where Devdutt thought of this fight is not clear. Perhaps Vedvyasa whispered these secrets to him. Perhaps.

In any case, second, it was Vyasa who advised Satyavati to retire to the forest.

A question that perhaps might be asked is, assuming that some version of the Mahabharata does indeed have a description of such a fight, why should an obscure version be given primacy, and that too without informing the reader that it is not from any of the generally accepted canonical versions.

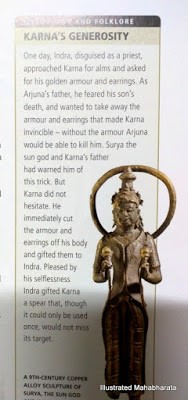

3. KARNA DONATES HIS EARRINGS AND ARMOUR

What the book says: when Indra, Arjuna’s celestial father, approached Karna and asked him for his earrings and armour, “Karna instantly gave them away.“

What the Mahabharata says: this episode is described in the Kundala-harana upaParva of the Aranyaka Parva. When Indra, disguised as a brahmana, asked Karna for his “natural armour and earrings,” Karna refused. Yes, he refused, saying, “I will not part with them.“

Devdutt gets it wrong, yet again, when writing that Karna “instantly gave them away.” To be clear, Karna did NOT instantly give away his earrings and armour. In fact, there is a considerable amount of back-and-forth between Karna and the brahmin (Indra in disguise).

Karna told Indra that he could take his earrings and armour only as an “exchange” or not at all – “Otherwise, I will not give them.” The exchange was Indra’s celestial weapon, the Shakti. The rest, as they say, is history; or shall we say “itihaas”?

The coarse black-and-white depiction of such a pivotal episode in the Mahabharata is antithetical to the exquisite subtlety in the epic. Devdutt’s distortion is melodramatic, but not faithful.

4. DEVAYANI and YAYATI

What Devdutt writes– “While helping her out, he had held her hand. Having done so, tradition demanded that he marry her. So Devayani married Yayati and went with him to his kingdom as his wife.“

What the Critical Edition says – “After pulling the one with beautiful hips out of the well, Yayati gently bid farewell and returned to his capital...

Devayani said, “O son of Nahusha! Earlier, no man except you has ever touched my hand. Therefore, in accordance with the dharma of accepting the hand, I accept you as my husband. My hand has been touched by you, who are a rishi and the son of a rishi. How can a proud one like me allow any other man to touch my hand?”…

Devayani said, “O father! This is the king who is Nahusha’s son. He grasped my hand when I was in trouble. Bestow me to him. I will accept no one else in the world as my husband.”“

[Adi Parva, Ch 73]

Once again, yet again, Devdutt’s interpretation is incomplete and incorrect. Devdutt’s interpretation would have one believe that Devayani had no choice but to let herself get married to Yayati because of the “demands” of “tradition”.

A lack of choice on the part of Devayani is implied here.

The Mahabharata suggests the opposite.

It was in fact Devayani who asked Yayati to marry her. Yayati was reluctant to do so – this also the Mahabharata tells us.

Devayani more or less forced the matter. Devdutt’s interpretation suggests the opposite.

Devayani went to her father and told him that Yayati was the one she had chosen as her husband.

Again, Devdutt has trouble accepting the fact that Devayani was a strong-willed woman with her own mind. He seems intent on portraying women in the Mahabharata as helpless and without the freedom of choice. Subjugation of the feminine is a trope, a western stereotype, that Devdutt perpetuates.

5. JAYADRATH’S DEATH

What Devdutt writes: “Drona was livid that despite his desperate measures, Jaydratha had been killed. He ordered his troops to continue fighting against the Pandavas after the sun had set...”

What the Mahabharata says: Drona was the commander of the Kaurava army at the time. The decision to order the army to continue fighting after sunset was indeed his. However, chapter 125 of Drona Parva tells us that after Saindhava (Jayadratha) was killed, Duryodhana sought out Drona and poured out his litany of woes in front of his guru, ending his tirade with an accusation that Drona had “always been partial towards your excellent disciple, Dhananjaya.” Drona felt hurt at these biting words and unfair accusations. After all, hadn’t Drona, just a day ago, told the Kauravas how to disarm and kill Abhimanyu? Drona now reminded Duryodhana of the fateful game of dice where he had refused to listen to Vidura’s advice. In Drona’s words, Duryodhana was “reaping the fruits of that adharma now.“

To say Drona was “livid” is a fanciful flight of imagination not supported by the Mahabharata.

“Desperate measures” is poetic license at best, or worse, a shoddy misrepresentation. Drona was clear that the blame for Jayadratha’s death could not be all lain at his door. He pointedly asked Duryodhana, “All of you surrounded Arjuna and sought to protect the king of Sindhu. How was he killed in your midst? O Kouravya! How was Saindhava killed when you, Karna, Kripa, Shalya and Ashvatthama were alive?” He finally ends chapter 126 with this pronouncement to Duryodhana, “The angry Kurus and Srinjayas will fight, even during the night.“

Therefore, Drona ordered the army to fight through the night only in response to Duryodhana’s accusatory tirade, and not out of any “lividness”.

6. UTTARAYANA

What Devdutt writes: “Bhishma chose to die on the auspicious day of Uttarayan, after the winter solstice, when the sun moves close to the Pole Star – the bright half of the lunar month, when the moon is waxing.“

What the Mahabharata says: the first chapter in the short Bhishma-Svargarohana Parva has this to say about Bhishma – “He saw that the sun had retreated and was proceeding towards uttarayana.“

Uttarayan is not a single day. Rather, Uttarayan refers to the six-month period between Makara Sankranti and Karka Sankranti. In some ways, one could refer to Uttarayan as the day when the sun starts to move towards the Northern Hemisphere (in a manner of speaking).

And whichever way one looks at it, Uttarayan has nothing to do with the lunar month. The “bright half of the lunar month,” as Devdutt refers to, is the Shukla-paksha, when “the moon is waxing.” Uttarayana has nothing, I repeat, nothing, to do with the waxing or waning of the moon. Devdutt is, again, hopelessly confused.

7. SHIKHANDI

Devdutt writes that Shikhandi’s “contribution

has been given little importance.“

This is an absurd remark.

Why? An entire Parva, the Ambopakhyana Parva, deals with Amba and Shikhandi’s backstory. This history is recounted by Bhishma on the eve of the war, which surely is a sign of the importance that the commander of the Kaurava army lent to Shikhandi. There are several passages during the course of the war that describe Shikhandi’s exploits in the war. Furthermore, the term Shikhandi itself has lived on and is remembered and used in several contexts even today, most often to refer to the use of a proxy in a fight against an enemy.

Again, Devdutt takes creative liberties with the facts.

8. Elders are subjugated. They are not. Perhaps they are.

In one place, the book talks about the “plight of old men and women and the way they are treated by their sons and daughters.”

Elsewhere, the book, and Devdutt talks about the “stranglehold of tradition over modernity“, where “a father demands and extracts a sacrifice from the son” and how the “older generation dominates society.“

So, by Devdutt’s logic, and certainly his words, the older generation on the one hand dominates society and where a father extracts a sacrifice from the son, and yet on the other hand the same older generation suffers a pitiable plight at the hands of its sons and daughters.

9. YAYATI COMPLEX

The story of Yayati is fascinating in its own right. Not only can one trace the history and divergence of the fates of the Kurus and Yadus dynasties from Yayati, but also the desires that burn in humans, the burning desire need to quench these infinite desires. It is parents who turn to their children to help fulfill these unsatisfied desires. But to phrase this so-called Yayati Complex as explaining “the stranglehold of tradition over modernity in Indian society” is a very, very western view of Indian society. Such a sweeping, simplistic stereotyping would fit more naturally inside the warped world of a Wendy Doniger. Given Devdutt’s cloying adulation of Wendy Doniger (notwithstanding his recent attempts to distance himself from her), perhaps it is no surprise.

10. PARASHURAMA FIGHTS BHISHMA

What Devdutt writes: “Parashurama gave up. ‘Since Bhishma is impossible to kill, this fight has to stop. If it continues, both of us will release weapons that will destroy the world,’ he said.”

What the Mahabharata says: After fighting for several days, Bhishma is told by brahmans in a dream to use the prasvapan weapon. It would put Parashurama to sleep, and since a foe asleep or dead on the battlefield was one and the same, Bhishma would have not only vanquished his opponent but also not incurred the sin of killing his guru. Eventually, Bhishma aimed the weapon at Parashurama. Narada appeared and advised him against releasing the weapon – “Do not use prasvapan. Rama is an ascetic with brahmana qualities. He is a brahmana and your preceptor. O Kouravya! You should never show him disrespect in any way.” Bhishma, recounting the battle to the Kouravas (Ch. 186 of Bhishma Parva), said, “I then withdrew the weapon prasvapan.”

“On seeing that the weapon had been withdrawn, Rama was enraged. He suddenly raised his voice and spoke these words. ‘I have been defeated by the extremely evil-minded Bhishma.’”

First, Parashurama did not “give up”.

Second, Parashurama himself accepted defeat.

Why Devdutt sees a need to distort even this is

not clear.

Why? Why? Why?

Devdutt is an unabashed and self-proclaimed fan of Wendy Doniger.

Wendy’s work on Hinduism has been shown to be marked by needless lies,

omissions, and distortions that have been called out innumerable times by

scholars, and yet which she has been unable to respond to. Her reputation as a

scholar in the West continues to thrive, despite an unending stream of

Hinduphobia that runs through her work on Hinduism and scholarly incompetence

that would have ended most academic careers.

It is entirely possible that Devdutt is subconsciously paying homage to his

idol by littering his work with the same kinds of errors and distortions that dog

Doniger’s work. It is perhaps, in his mind, the ultimate act of submission, an

intellectual prostration, of submission and self-degradation in an attempt to

get the validation from a Hinduphobe.

Part 2

Devdutt’s Rejoinder

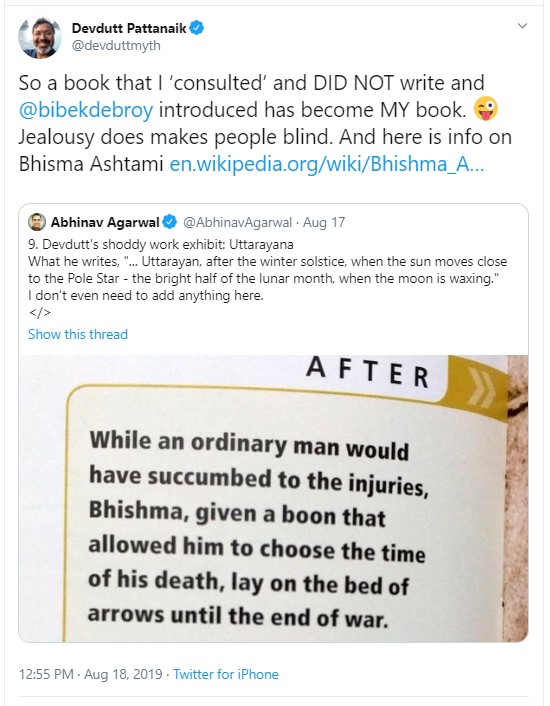

In response to the considerable traction my tweets attracted, Devdutt did respond with one tweet (https://twitter.com/devduttmyth/status/1162988792627601408).

That prompted me to dig deeper into his other work, Jaya.

To his point that he “DID NOT write” the book, I turned to the book that he has written – “Jaya”, and compared the two.

Gandhari episode

What the Illustrated Mahabharata has: “Gandhari decided to force the child out of her. She ordered her maids to strike her belly with an iron bar.“

What Devdutt writes in Jaya: Ch 15 – Birth of Gandhari’s Children: “Gandhari ordered her maids to get an iron bar. ‘Now strike me on my belly with it,’ she ordered. The maids hesitated. ‘Do it,’ shouted Gandhari. With great reluctance, the maids did as they were told, and struck the queen on her belly. ‘Again. Strike me again. Again and again,’ said Gandhari. The maids kept striking her until Gandhari’s womb quivered and pushed out a ball of flesh, cold as iron.”

Is there any material difference between the two?

Satyavati’s Departure

From The Illustrated Mahabharata: Satyavati “decided to leave the palace on witnessing a public fight between the Pandavas and Kauravas.”

What Devdutt wrote in Jaya: Ch 21 – The graduation ceremony – “Watching her great grandsons snarl at each other like street dogs, Satyavati took a decision. ‘I see this family I worked so hard to create will soon destroy itself. I cannot bear to see it. I will therefore go to the forest.’”

Again, no material difference between the two. Yet Devdutt insists that he “DID NOT write” those words.

Karna

But things now got interesting, since I was leafing through “Jaya” and spotting casual lies and misrepresentations on almost every page. To wit, here are some examples:

What Devdutt wrote in In Jaya: Ch 82 – Death of Abhimanyu – “When it was time for him to finally enter, after Bhishma’s death, an old man came to him, at dawn, begging for alms.”

What the Mahabharata tell us: Indra took away Karna’s kavacha and kundela much before the war. This episode is described in an upa-parva of its own, “Kundala-aharana Parva”, the 43rd upaParva. After this episode the Pandavas spend a year in agyata-vaasa, go-grahana happens, Uttaraa is married to Abhimanyu, the entire Udyoga parva takes place where back-and-forth negotiations take place between the Pandavas and Kouravas to avert the war, the war starts, Bhishma is killed (or rather, defeated), Abhimanyu is killed, Jayadratha is killed, then Drona, and only then does Karna become the commander of the Kaurava army.

Sanjay

What Devdutt wrote in Jaya: Ch 103 – The elders renounce the kingdom – “Sanjay followed his master to the forest and died with them in the forest fire, such was his loyalty to the old, blind king.”

What the Mahabharata says: In the Naradagamana upa-parva of the Ashramavasika Parva (Ch. 45), Narada tells us, “But Sanjaya, the great adviser, escaped from the conflagration. I saw him on the banks of the Ganga, …The suta, Sanjaya, next left for the Himalaya mountains.”

The Mahabharata tell us that Sanjay survived the terrible fire in the forest. Devdutt kills off poor Sanjay. Why? One wonders.

Part 3

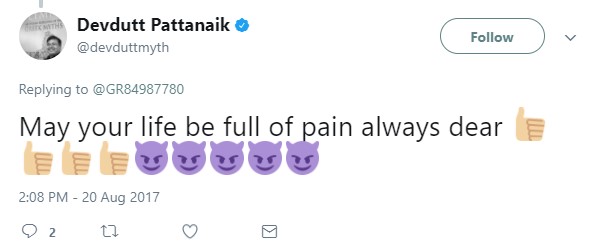

A sample of Devdutt’s tweets, offered without comment.

Featured Image: Amazon, Devdutt

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Abhinav Agarwal is a son, husband, father, technologist and an IIM-B Gold Medalist.