The Śaka era was popularly used for dating in the ancient and medieval period inscriptions and literature in India, Nepal, Burma, Cambodia and Java (Indonesia). It is generally believed by the historians that the Śaka era commenced in 78 CE. Prof. F. Kielhorn published an article “On the dates of the Śaka Era in inscriptions” in 1894 and verified more than 370 references to the Śaka era with the presumption of 78 CE as the epoch.1 He found that the calculations of about 140 dates “satisfy the requirements”, whereas that of 70 dates were “unsatisfactory”. He also claimed that the details of more than 30 dates are doubtful and that around 100 dates contain no details for verification. Based on this analysis, JF Fleet and Kielhorn declared some of the inscriptions and texts as “spurious”, because the details therein did not reconcile to the epoch of 78 CE. Surprisingly, Fleet and Kielhorn even alleged that some of these inscriptions are forgeries though at the same time accepting the information selectively from these sources. Unfortunately, Indian epigraphists also accepted these inscriptions as ‘spurious’ or ‘forgeries’ without any further verification.

Let us make one more serious effort to read the so-called ‘spurious’ or ‘forged’ inscriptions of the Śaka era to ascertain whether these are really spurious epigraphs or they run contrary to certain concocted theories.

There are two theories related to the epoch of the Śaka era:

- The Śaka era and the Śakānta or Śakakālātīta era are identical and both commenced in 78 CE.

- The Śaka era and the Śakānta era are not identical and the Śaka era originated much before 78 CE, whereas the Śakānta era commenced in 78 CE.

While reading the inscriptions and texts of the Śaka era, we can easily distinguish two different ways of referring to the reckoning of the Śaka era. Some epigraphs unambiguously refer to the epoch of the Śaka era from the coronation of the Śaka king, whereas some epigraphs refer to the epoch of the Śaka era from the killing of the Śaka king or the end of the Śaka era. The epigraphic and literary references of the Śaka era can be categorised as shown below:

From the coronation of From the killing of the Śaka King

the Śaka King or the end of the Śaka era

Śaka-nrpati-rājyābhisheka-samvatsare Śaka-nrpa-kālātīta-samvatsara-śateshu

Śakavarsheshu-atīteshu Śaka-varshātīta-samvatsare

Śaka-bhūpa-kāla, Śakendra-kāla Jāte Śakābde tataḥ, Śakendre atigate

Śaka-nrpa-kālāt or Śakānām kālāt Yāte kāle Śakānām,

Śaka-nrpa-kālākrānta-samvatsara Śakānte, Śakāntataḥ

Śaka-nrpa-kālātīteshu, Śaka-nrpa-kālātīte Śaka-nrpa-kālātīta-samvat

Śakānāmapi bhūbhujām gateshu abdeshu

Śaka-prthivīpateḥ varshāṇām

Śaka-nrpa-samaye, Śaka-kśitīśābda

Śaka-kālād-ārabhya, Śakābdānām pramāṇe

Śakābde, Śāke

Any scholar with a basic knowledge of Sanskrit can make the distinction in the meaning of the references segregated above. Evidently, one set of references leads to the coronation of the Śaka king, whereas the other set of references leads to the end of Śaka era or the killing of the Śaka king. How can the totally different references “Śaka-nrpati-rājyābhisheka-samvatsara” and “Śaka-nrpa-kālātīta-samvatsara” lead to the same epoch? Prima facie, the epigraphs that refer to “Śaka-nrpa-kāla” denote an older epoch than the epigraphs that refer to “Śaka-nrpa-kālātīta-samvatsara”. Bhaskaracharya, the author of Siddhānta Śiromaṇi, clearly mentions the existence of the Śaka era or Śakābda prior to the killing of the Śaka king.

Yātāḥ shaṇmanavo yugāni bhamitānyanyadyugāṅghritrayam,

Nandādrīnduguṇās (3179) tathā Śakanrpasyānte kalervatsarāḥ ǀ

Godrīndvadrikrtāṅkadasranagagocandrāḥ (1972947179) Śakābdānvitāḥ

Sarve samkalitāḥ pitāmahadine syurvartamāne gatāḥ ǁ 2

In this verse, Bhāskara states that 3179 years elapsed from the beginning of Kaliyuga to the end or the killing of the Śaka king and 1972947179 years elapsed from the starting of Kalpa till the killing of the Śaka king, including the years of Śakābda i.e. Śaka era. The word “Śakābdānvitāḥ” explicitly indicates the existence of the epoch of Śakābda or the Śaka era prior to 78 CE. Lallāchārya, the author of “Śishyadhīvrddhidatantra”, also clearly indicates that the Śakakśitīśābda i.e. Śaka era existed prior to 78 CE.

“Nandādricandrānala (3179)-samyuto bhavet, Śakakśitīśābda-gaṇo gataḥ kaleḥ ǀ

Divākaraghno gatamāsa-samyutaḥ, Khavahninighnasthitibhiḥ samanvitaḥ ǁ 3

Elaborating the above verse, Mallikārjuna Sūri, a commentator on “Śishyadhīvrddhidatantra”, also makes a similar statement as “Śakanrpābdagaṇah sahasratrayeṇaikonāśītyadhika-śatena (3179) sahitaḥ Kaligatābda-gaṇo bhavati”. It is evident that Lalla and Mallikārjuna Sūri explicitly state here that “3179 Kali years are elapsed including the years of the Śaka era”.

Thus, Indian astronomers like Bhaskara and Lalla clearly indicate the existence of an old epoch of the Śaka era prior to 78 CE. They refer to the epoch of 78 CE as the end of the Śaka king. The use of the words “atīta” or “gata” twice in the Surat plates of Rashtrakuta Karkaraja4 and the Kauthem plates of Western Chalukya king Vikramaditya5 (Śaka-nripa-kālātita-samvatsara-śateshu…. atīteshu), “Yashastilaka Campū” of Somadeva Suri (Śaka-nripa-kālātita-samvatsara-śateshu…. gateshu) and “Lakśaṇāvati” of Udayana (Atīteshu Śakāntataḥ varsheshu) unambiguously refers to the epoch of 78 CE as the era commenced from the end of the era of Śaka king. The Rājapura plates of Madhurāntakadeva6 also clearly refer to the epoch as “Śaka-nrpa-kālātīta-Samvat 987”, which means “Śaka-nrpa-kāla-Samvat” was different from “Śaka-nrpa-kālātīta-Samvat”. Al-Beruni also refers to the epoch of the Śaka era as the killing of the Śaka king.7 Thus, the epoch of the coronation of the Śaka king and the epoch of the end or the killing of the Śaka king are not the same, but two different epochs.

It is well known that the epoch of the killing of the Śaka king commenced in 78 CE. Now the question is what is the epoch of the Śaka era that commenced from the coronation of the Śaka King? To answer this question, we have to study the verifiable details of inscriptions of the Śaka era carefully. I have based my verification of the date and time of eclipses on the comprehensive data on eclipses from the website of NASA.8 The inscriptions of the Early Chalukyas of Badami explicitly refer to the epoch of the coronation of the Śaka king. The Kurtakoti copper plates of the Early Chalukyas provide unambiguous leads to the epoch of the coronation of Śaka king as being commenced in 583 BCE.

The selected text from the Kurtakoti copper plates reads9: “Viditamastu sosmābhiḥ ba[va] trimśottara-pañca-śateshu Śakavarsheshu atīteshu, vijayarājya-samvatsare shoḍaśavarshe pravartamāne, Kiśuvojala-mahānagara-vikhyāta-sthitasya Vaiśākha-Jyeshṭha-māsa-madhyamāmāvāsyāyām bhāskaradine Rohiṇyarkśe madhyāhnakāle Vikaramādityasya………… mahādevatayorubhayoḥ Vrshabharāśau tasmin Vrshabharāśau Sūryagrahaṇa sarvamāsī (Sarvagrāsī) bhūte…………”

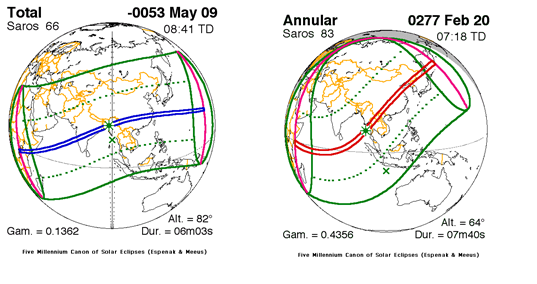

The Kurtakoti plates are dated in the year 530 elapsed from the epoch of the coronation of the Śaka king. It refers to the total solar eclipse that occurred on the new moon day of the Vaiśākha month in Northern Karnataka which ended around noon. The following ten total solar eclipses occurred in Northern Karnataka (considering the latitude 15:55 N and longitude 75:40 E of Badami) during the period 1500 BCE to 1500 CE..

| 1. 13th Aug 1416 BCE 2. 27th Jul 1257 BCE 3. 4th Mar 180 BCE 4. 9th May 53 BCE 5. 27th Jan 111 CE | 6. 25th Jun 754 CE 7. 20th Aug 993 CE 8. 23rd Jul 1134 CE 9. 6th Nov 1268 CE 10. 9th Dec 1322 CE |

The data shows that there was only one total solar eclipse that occurred in Northern Karnataka on the new moon day of the Vaiśākha month, i.e. 9th May 53 BCE that started at 09:04 hrs and ended at 11:45 hrs. The day was the new moon day of the Vaiśākha month (between Vaiśākha and Jyeṣṭha months) and the moon was in Rohiṇī nakśatra. The Sun and Moon were also in Vṛṣabha rāśi i.e. Taurus sign. The day was “Bhāskara dina” meaning Sunday, but it cannot be verified with reference to the modern Indian calendar. It depends on the Siddhānta of Ahargaṇa (for calculating the number of days for a specified date with reference to an original epochal date) considered in the calendar used during those days.

An inscription found in Shimoga district of Karnataka refers to an annular solar eclipse (Valaya grahaṇa) that occurred on Chaitra pratipadā, i.e. the 1st tithi of the bright fortnight of Chaitra month in the year 861 of the Śaka era.10 Considering the epoch of the coronation of the Śaka king in 583 BCE, 277-278 CE was the 861st year of the Śaka era and the annular solar eclipse occurred on 20th Feb 277 CE that ended at 11:39 AM. Interestingly, Phālguna Amāvāsyā ended at 11:00 AM and Chaitra Pratipadā started at the same time.

It may be noted that the total and annular solar eclipses are the strongest evidences to fix the epoch of an era. The epoch of 583 BCE perfectly explains these eclipses, whereas the epoch of 78 CE miserably fails to do so. There are many epigraphic references of irregular eclipses, which cannot be explained with reference to the epoch of 78 CE. It is also observed that most of the inscriptions that refer to irregular eclipses are dated in the epoch of the coronation of the Śaka king and not in the epoch of the killing of the Śaka king. If we consider two different epochs of the Śaka era as proposed above, most of the epigraphic references of irregular eclipses can be satisfactorily explained as attempted below.

It may be noted that the total and annular solar eclipses are the strongest evidences to fix the epoch of an era. The epoch of 583 BCE perfectly explains these eclipses, whereas the epoch of 78 CE miserably fails to do so. There are many epigraphic references of irregular eclipses, which cannot be explained with reference to the epoch of 78 CE. It is also observed that most of the inscriptions that refer to irregular eclipses are dated in the epoch of the coronation of the Śaka king and not in the epoch of the killing of the Śaka king. If we consider two different epochs of the Śaka era as proposed above, most of the epigraphic references of irregular eclipses can be satisfactorily explained as attempted below.

Solar eclipses mentioned in the inscriptions dated in the Śaka era (583 BCE):

- The Hyderabad Plates of Pulakesin II:11 Śaka 534 elapsed (49-48 BCE), the new moon day of Bhādrapada month and solar eclipse. The date corresponds to 21st Aug 49 BCE.

- The Talamanchi Plates of Vikramaditya:12 The 6th regnal year i.e. Śaka 582 elapsed (1-0 BCE), the new moon day of Śrāvaṇa month and solar eclipse. The date corresponds to 31st July 1 BCE.

- The Barsi Plates of Rashtrakuta Krishnaraja I:13 Śaka 687 current (103-104 CE), the new moon day of Jyeṣṭha month and solar eclipse. The date corresponds to 22nd June 103 CE.

- The Talegaon plates of Rashtrakuta Krishnaraja I:14 Śaka 690 current (106-107 CE), the new moon day of Vaiśākha month and solar eclipse. The date corresponds to 21st Apr 106 CE and a solar eclipse was visible between 16:56 hrs to 18:28 hrs.

- The Perjjarangi grant of Ganga Rajamalla I:15 Śaka 741 elapsed (158-159 CE), Solar eclipse. A solar eclipse was visible on 13th July 158 CE between 14.03 hrs to 15.19 hrs.

- The Nimbal inscription of Bhillama’s Feudatory:16 The 3rd Regnal year of Billama i.e. Śaka 1110 (526-527 CE), the new moon day of Bhādrapada, Solar eclipse and Saṁkramaṇa (Tulā Saṁkrānti). The date corresponds to 22nd Sep 526 CE.

- The Devur inscription of Jaitugi’s feudatory:17 Śaka 1118 (534-535 CE), solar eclipse during Uttarāyaṇ The date corresponds to 29th Apr 534 CE.

- The Devangav inscription of Jaitugi’s feudatory:18 Śaka 1121 (537-538 CE), Solar eclipse on the new moon day of Māgha month. The date corresponds to 15th Feb 538 CE.

- The Khedrapur inscription of Singhana:19 Śaka 1136 (554-555 CE), Solar eclipse on the new moon day of Chaitra month. The date corresponds to 19th Mar 554 CE.

- The Jettigi inscription of Krishna:20 Śaka 1178 (594-595 CE), Solar eclipse on the new moon day of Pausha month. The date corresponds to 16th Jan 595 CE.

- The Hulgur inscription of Mahadeva:21 Śaka 1189 (606-607 CE), Solar eclipse on the new moon day of Jyeṣṭha The date corresponds to 11th June 606 CE.

Lunar eclipses mentioned in the inscriptions dated in the Śaka era (583 BCE):

- The Altem Plates of Pulakesin I:22 Śaka 411 elapsed (172-171 BCE), the full moon day of Vaiśākha month, Viśākhā nakśatra and lunar eclipse. The date corresponds to 19th Apr 172 BCE.

- The Kendur plates of Kirtivarman II:23 Śaka 672 current (88-89 BCE), the full moon day of Vaiśākha month and lunar eclipse. The date corresponds to 24th Apr 88 CE.

- The Manne plates of Govinda III:24 Śaka 724 (140-141 CE), lunar eclipse and Puṣya nakśatra. A lunar eclipse was visible on 11th Dec 140 CE from 19:57 hrs to 1:22 hrs.

- The Manne plates of Govinda III:25 Śaka 732 elapsed (149-150 CE), the full moon day of Pauṣa month, Puṣya nakśatra and lunar eclipse. A lunar eclipse was visible on 2nd Dec 149 CE in North Karṇāṭaka around 20:45 hrs to 22:11 hrs.

- The Kottimba grant of Mārasiṁha:26 Śaka 721 (139-140 CE), Śrāvaṇa, śuddha pūrṇimā, Daniṣṭhā nakśatra, lunar eclipse. The date corresponds to 29th July 139 CE, Śrāvaṇa Pūrṇimā and the nakśatra was Dhaniṣṭhā. A lunar eclipse was visible between 4:18 hrs to 5:51 hrs.

- The Gattavadipura grant of Rājamalla III:27 Śaka 826 elapsed (243-244 CE), Mārgaśīrṣa month, the full moon day, Mṛgaśirā nakśatra, lunar eclipse. A penumbral lunar eclipse was visible on 14th Dec 243 CE.

- The Patna inscription of Soideva:28 Śaka 1128 elapsed (545-546 CE), the full moon day of Śrāvaṇa month and lunar eclipse. The date corresponds to 6th September 545 CE.

- The Kolhapur Stone Inscription:29 Śaka 1065 elapsed (482-483 CE), the full moon day of Māgha month and lunar eclipse. The date corresponds to 10th January 483 CE. A penumbral lunar eclipse was visible at Kolhāpur from 4:34 hrs to 5:54 hrs.

- The Bamani Stone Inscription:30 Śaka 1073 elapsed (490-491 CE), the full moon day in Bhādrapada nakśatra or Bhādrapada month and a lunar eclipse. The date corresponds to 14th September 490 CE. A penumbral lunar eclipse was visible from 22:50 hrs to 00:52 hrs.

These are just a few examples of verifying the astronomical details given in the inscriptions with reference to the epoch of 583 BCE.

Other evidences of the epoch of the Śaka era (583 BCE):

- Cunningham and JF Fleet observed that certain ancient Indian almanacs show the period from 5th April 1886 CE to 24th March 1887 CE as corresponding to the Śaka year 1808 elapsed, whereas other almanacs show the period from 6th March 1886 CE to 22nd February 1887 CE as corresponding to Śaka year 1808 elapsed. JF Fleet also confirms that the tables of these almanacs undoubtedly took the Śaka year 1808 as elapsed31. Evidently, there were two traditions in the Śaka calendar. Now the question is: if both Pañcāṅgas have followed the same epoch, how could the beginning of the New Year differs by one month? Interestingly, JF Fleet argues that there was a long interval between the epoch of the coronation of Śaka king and the epoch of the killing of the Śaka king and therefore, these two epochs are not identical. Surprisingly, he quotes the inscription of Chālukya Maṅgaliśa, which refers to “Śaka-nṛpati-rājyābhiṣeka-saṁvatsare” and states that the epoch of the Śaka era initially originated in an extension of regnal years of the Śaka king. When astronomers came to adopt it as an astronomical era, they established an exact epoch of 78 AD by reckoning back from the regnal year then current. He clearly admits that the epochs of both Pañcāṅgas cannot be identical, but he takes only one-year difference between these two epochs without citing any supporting evidence. In reality, the epoch of the coronation of the Śaka king commenced as the reckoning of regnal years from 583 BCE, whereas the epoch of the Śakānta or Śakakālātīta (the killing of the Śaka king) is an astronomical era that commenced in 78 CE.

(Note: The epoch of 78 CE was actually started from 1st April 78 CE when sun, moon and Jupiter were in conjunction in Aries 0′. According to the old Saka calendar (583 BCE) and the old method of intercalation, Chaitra sukla pratipada was on 1st April 78 CE. Though the epoch changed from 583 BCE to 78 CE, but this old tradition continued using the old calendar starting the year 78 CE from 1st April 78 CE. Since the Indian astronomers fixed 3179 (78 CE) years as an astronomical epoch, it was necessary that the years 3179 must have an accurate Ahargana (Counting of days) for 3179 years. Indians took 365.2586 days per year. If we multiply 3179 * 365.2586, it indicates that total 1161157 days elapsed. Starting from Kali epoch, 1161157th day elapsed on 17th Mar 78 CE. It was Purnima on 17th Mar 78 CE. This is exactly why Purnimanta Calendar starts from 18th Mar 78 CE. The followers of Amanta calendar fixed the date of New Year on 3rd March 78 CE. Thus we have three dates for the beginning of New Year 78 CE. New Amanta Calendar started from 3rd March 78 CE; Purnimanta Calendar started from 18th Mar 78 CE; and Old Amanta calendar started from 1st Apr 78 CE. This is the reason why one month differs in two calendars in 1886 CE.)

- The Hisse Borala inscription of Vākātaka Devasena32 mentions that Saptarṣis were in Uttara Phālguni nakśatra in Śaka 380 (204-203 BCE) [Saptarṣayaḥ Uttarāsu Phālgunīṣu adbe Śakānām 380]. Vriddha Garga and Varāhamihira mentioned that Saptarṣis were in Maghā 2526 years before the epoch of the Śaka era33. Considering the epoch of the Śaka era in 583 BCE, Saptarṣis were in Maghā around 3109 BCE (3176-3076 BCE). According to Indian tradition, Saptarṣis stay 100 years in each of 27 nakśatras indicating the cycle of 2700 years. Considering the forward motion, Saptarṣis were again in Magha around 476-376 BCE, in Purva Phālguni around 376-276 BCE and in Uttara Phālguni around 276-176 BCE. Exactly, this inscription states that Saptasrṣis were in Uttara Phālguni in 204-203 BCE. This cannot be explained if we consider the only epoch of 78 CE.

- It appears that the calendar of the epoch of the Śaka era (583 BCE) existed till the 15th century CE. An inscription of Hoysala King Ballāla is dated Śaka 1919 (1336 CE)34. The Nilavara inscription of Mallikārjuna is dated Saka 1975 (1392 CE) and also the inscription35 found at the village of Bittaravalli, Belur taluka, Karṇātaka is dated in Śaka 2027 (1444 CE) [Śakavarṣada 2027 neya Ānanda Saṁvatsara Bhādrapada śuddha padiva śukravāradandu]36. Interestingly, the year 1919, 1975 and 2027 in the Śakānta or Śakakālātīta era (78 CE) will be the year 1997, 2053 and 2105. Evidently, the dates of these three inscriptions cannot be explained in the epoch of the Śakānta or Śakakālātīta era (78 CE).

- The earliest reference to the Śaka era (583 BCE) is found in the last chapter of Yavanajātaka. Gate ṣaḍagre’rdhaśate samānām, Kālakriyāntattvamidam Śakānām ǀ Raviryuge Sūryadine prapede, kramāt tadabdādi yugādi bhānoḥ ǁ 37One of the main features of Yavanajātaka is the use of a solar Yuga or an astronomical cycle of 165 years. Indicating the date of the epoch of a solar Yuga of 165 years with reference to the Śaka era, it is stated that when the 56th year of the Śakas is current (can also be interpreted as elapsed), on a Sunday, the beginning of that year is the beginning of the yuga of the sun. Considering the epoch of the Śaka era in 583 BCE, the 56th year was 528-527 BCE. The date was 12th March 528 BCE, when the conjunction of the Sun and Moon occurred at Meśa (Aries) 0o. Interestingly, David Pingree distorted the phrase “ṣaḍagre’rdhaśate” (56th year) as “ṣaḍ eke’rdhaśate” (66th year) deliberately to match the astronomical facts described in the verse with reference to the epoch of 78 CE.

- The Pimpari plates of Rashtrakuta king Dhruvaraja38 are dated in the year 697 of Śakānta or Śakakālātīta era (775 CE). Historians identified this Dhruvaraja to be Dhruva I. King Dhruvaraja of this grant, explicitly mentions about his ancestor, Rashtrakuta king Dhruvaraja, who was the younger brother of Govindaraja [tasyānujaḥ Śri-Dhruvarājanāmā Mahānubhāvo vihitapratāpaḥ prasādhitāśeṣa-narendrachakraḥ krameṇa bālārka-vapur babhūva]. If the Dhruvaraja of Pimpari plates were the Dhruva I, how can he say “babhūva” for himself? The word “babhūva” means existed or flourished once upon a time. At least, “babhūva” cannot be used for the reigning king. Interestingly, Dhulia grant39 of Karkaraja, dated in Śakakālātīta 701 (779 CE) was issued in the victorious reign of Prabhutavarsha Govindaraja and it used “babhuva” for Dhruvaraja. Therefore, the Dhruvaraja of Pimpari grant was undoubtedly Dhruva II and not Dhruva I.

- The Bagumra grant of Karka Suvarnavarsha40 dated in Vaiśākha month of Śakakālātīta 734 mentions Govindaraja III and his younger brother Indraraja, the first Rashtrakuta king of Lātadeṣa as the kings of the past. It clearly addresses Govindaraja III as “Kīrtipuruṣa” (Babhūva Kīrtipuruṣo Govindarājaḥ sutaḥ) and his younger brother Indraraja as “Adbhuta-Kīrti-Sūtiḥ” (Śrimān bhuvi kśmāpatir Indrarājaḥ, Śāstā babhūva adbhuta-Kīrti-sūtis tadāpta-Lāteśvara-mandalasya). The reference of Kīrtipuruṣa and the use of the verb “Babhūva” in the remote past unambiguously tell us that Govindaraja III died long back. If so, how the Kadamba grant of Prabhutavarsha Govinda41 was issued in the year 735 of Śakakālātīta era, the Lohara grant of Prabhutavarsha42 was issued in the year 734 (the new moon day of Mṛgaśira month), the Dhulia grant of Govindaraja43 in the year 735, the Torkhede grant of the time of Prabhutavarsha Govindaraja44 in the year 735 and the Devli plates of Prabhutavarsha Govindaraja45 were issued in Valabhi era 500 i.e. the year 741. Similarly, Indraraja was mentioned as “Adbhuta-Kīrti-Sūtiḥ” means the king, who had a great and glorious progeny. If Indraraja died around Śakakālātīta 734, then he could be barely 35 or 40 years old because Govindaraja II, the elder brother of his father Dhruvaraja was referred to as “Yuvaraja” in the Alas plates46 dated in the year 692. Moreover, it is also stated in Bagumra grant that even today, the Suras, the Kinnaras, the Siddhas, the Sadhyas etc. sing the fame of Indraraja (Adyāpi yasya Sura-Kinnara-Siddha-Sādhya-Vidyādharādhipatayo guṇa-pakśpātāt, gāyanti kunda-kusuma-sri yaś…). This statement apparently indicates that Indraraja had flourished at least few hundred years back. These serious inconsistencies can be easily explained if we segregate the inscriptions of Rashtrakutas with reference to the epoch of the Śaka era (583 BCE) and the epoch of Śakānta or Śakakālātīta era (78 CE).

- Interestingly, the Pimpalner grant47 dated in Śakānta or Śakakālātīta 310 (388 CE) is the earliest grant that refer to the Śaka-nṛpa-kālātīta era, indicating the beginning of the use of the Śakānta or Śakakālātīta era in the 4th century CE. The Itagi,48 Pali,49 Dharwar50 and Boargaon51 plates of Vinayāditya dated from the year 516 (594 CE) to 520 (598 CE) also refer to the Śaka-nṛpa-kālātīta era. The Pimpalner grant and the grants of Vinayāditya are the strongest evidence to establish that the Śaka era existed prior to 78 CE, but historians rejected them as forgeries, because these inscriptions are written in the Nagari script, whereas the inscriptions of early Chalukyas are written in the Southern script that was in vogue prior to the birth of Nagari script. In fact, the inscriptions of early Chalukyas refer to the epoch of Śaka era (583 BCE) and the Pimpalner grant of Satyashraya and the grants of later Chalukya king Vinayaditya refer to the epoch of Śakakālātīta era (78 CE).

- The Buddhist literature and traditions of Burma and Thailand refer to two different epochs of the Śaka era i.e. Mahasakkaraj era and Chulasakkaraj era. Maha means greater and Chula means lesser. It may be noted that the reference of the Mahasakkaraj era and the Chulasakkaraj era or the greater Śaka era and the lesser Śaka era is itself an evidence to prove that there were two different epochs of the Śaka era. One was the greater (583 BCE) and another was the lesser (78 CE). Since the epoch of 583 BCE was forgotten, historians mistakenly concluded that Mahasakkaraj era commenced in 78 CE whereas Chulasakkaraj era commenced in 638 CE.

Based on the critical study of the epigraphic and literary references of the Śaka era and the verifiable details of the inscriptions as attempted above, it can be unhesitatingly concluded that the epoch of the Śaka era and the epoch of the Śakānta or Śakakālātīta era are not identical. The epoch of the Śaka era commenced from the coronation of the Śaka king in 583 BCE, while the epoch of the Śakānta or Śakakālātīta was introduced by Indian astronomers in 78 CE. The era that commenced from the coronation of the Śaka king was referred to as “Śaka-nṛpa-kāla”, “Śaka-varṣa” etc. and the era that commenced from the killing of the Śaka king was referred to as “Śakānta”, “Śaka-nṛpa-kālātīta” etc. The compound word “Śaka-nṛpa-kālātīta-saṁvatsara….” has been misinterpreted as “the years elapsed from the era of the Śaka king” considering it Pañcami or Saptami tatpuruṣa compound as “Śaka-nṛpa-kālāt or Śaka-nṛpa-kāle atītāḥ saṁvatsarāḥ, teṣu”. In fact, it is Dvitīyā tatpuruṣa compound as “Śaka-nṛpa-kālaṁ atītaḥ = Śaka-nṛpa-kālātītah, tasmāt saṁvatsarāḥ, teṣu” which means “the years from the end of the era of the Śaka king”. In a few instances like the Behatti grant of Kalachuri Singhana52 and Puruśottampuri grant of the Yādava king Rāmachandra,53 the compound “Śaka-nṛpa-kālātīta” was used as Pañcami or Saptami tatpuruṣa. The Surat plates of Rāṣṭrakūṭa karkarāja and the Kauthem plates of Vikramāditya recorded the date as “Śaka-nṛpa-kālātīta-saṁvatsara-śateṣu…. atīteṣu”, which is irrefutable evidence that “Śaka-nṛpa-kālātīta” is the compound word of Dvitīyā tatpuruṣa and not Pañcami or Saptami tatpuruṣa. The poet Somadeva Sūri also refers to the date of his work “Yaśastilakachaṁpū” as “Śaka-nṛpa-kālātīta-saṁvatsara-śateṣvaṣṭasvekāśītyadhikeṣu gateṣu….”. It is totally absurd to use “atīteṣu” or “gateṣu” again in case “Śaka-nṛpa-kālātīta” is Pañcami or Saptami tatpuruṣa compound.

The origin of the Śaka era (583 BCE)

Jain sources inform us that Kālakāchārya invited the Śakas to take revenge against Gardabhilla, the King of Ujjain. The Śakas defeated Gardabhilla and reigned for four years in Ujjain. King Vikramaditya drove the Śakas away and founded the Malava kingdom. After 135 years, the Śakas returned again and conquered Ujjain in the 6th century BCE. In all probability, Caṣṭana, the king of Śakas, introduced an epoch from the date of his coronation i.e. 19th February 583 BCE54. Gradually, this epoch of the Śaka era became popular in North-Western India and also in South India. The kingdom of the Śakas declined in the 3rd century BCE. Though the rule of the Śakas ended, the popular use of the epoch of the Śaka era (583 BCE) continued.

The origin of the Śakānta or Śakakālātīta era (78 CE)

Indian astronomers were in search of a perfect epoch for all round astronomical calculations, because they realized that the traditional epoch of Kaliyuga (3102 BC) did not begin with a perfect conjunction. They were looking for a perfect conjunction of Sun, Moon and one major planet (Jupiter or Saturn). Finally, they found a perfect and rarest conjunction of Sun, Moon and Jupiter in Meṣa Rāśi (Aries) on Śukla Pratipadā and Aśvini nakśatra, i.e. 1st April 78 CE. Thus, Indian astronomers fixed the epoch of 78 CE and referred to it as Śakānta (the end of the Śaka era of 583 BCE). This epoch of 78 CE was generally used by Indian astronomers till the 10th and 11th century CE and was known as Śakānta i.e. the death of the Śaka king. Al Beruni also confirms that the death of the tyrant (Śaka king) was used as the epoch of an era (78 CE), especially by the astronomers55.

Though, the epoch of 78 CE was generally used by Indian astronomers, the earliest use of this epoch is witnessed in the Pimpalner grant of Chalukya Satyashraya dated in the year 310 and four grants of Chalukya Vinayaditya dated in the years 516 to 520. Interestingly, the epoch of 78 CE was referred to as “Śaka-nṛpa-kālātīta” in the inscriptions to distinguish it from the epoch of 583 BCE, which was popularly referred to as “Śaka-varṣa”, “Śaka-nṛpa-kāla”, etc. Since historians were ignorant of the difference between the epochs of the Saka and Śakakālātīta era, they mistakenly declared these grants as forgeries.

The epoch of Śaka-nṛpa-kālātīta era (78 CE) started gaining popularity in South India from the 8th century onwards. Gradually, Indians forgot the epoch of the Śaka era (583 BCE) in due course of time and the use of the similar expressions like “Śaka-varṣada”, “Śakabde”, “Śaka”, etc., for both the Śaka era and the Śaka-nripa-kālātīta era in the inscriptions also complicated the problem of distinguishing between these two eras. When Al Beruni visited India in the 11th century, Indians generally knew only one epoch of the Śaka era, i.e. the killing of the Śaka king that commenced in 78 CE.

The legend of Śālivāhana

A Tamil Manuscript of Chola Purva Patayam (the history of ancient Cholas) collected by Mackenzie56 gives an interesting account of King Śālivāhana. It states that Śālivāhana was born in Ayodhya (probably, a mistake for Ambāvati or Amarāvati near to Pratishthāna as mentioned in Śālivāhana-Charita) in a potter’s house with the blessings of Adi Shesha. He conquered Vikramaditya and subdued Ayodhya (Avanti?) country. He founded an era termed as the era of Śālivāhana. It is also recorded that Śālivāhana was a Samana, a worshipper of Sarveshvarer (a worshipper of Adi Shesha?) of a venomous spirit. In his time, there was a great disorder. Ancient rites and institutions were neglected. He overthrew all privileges, which derived from Vikramaditya. The three kings, Vira Chola of Cholas, Ulara Cheran of Cheras and Vajranga Pandyan of Pandyas came together and vowed to destroy Śālivāhana. Finally, these three kings unitedly fought and killed Śālivāhana in Kali year 2443 (659 BCE) [The scribe of the manuscript might have mistakenly mentioned 1443 instead of 2443]. Ain-i-Akbari of Abul Fazal gives the date of King Śālivāhana around 670 BC. Kalidasa’s Jyotirvidābharanam also mentions a king Śālivāhana who founded an era before the Kali year 3068 (34 BC)57.

Evidently, the story of the meteoric rise of King Śālivāhana in the 7th century BCE became a legend particularly in Vaishnavism. King Śālivāhana might have founded an era before 583 BCE, but the rise of the Śakas made the use of the epoch of 583 BCE more popular. The rule of the Śakas declined in the 3rd century BCE, but the use of the epoch of 583 BCE was continued. It appears that Indians, particularly Vaishnavas started believing that the epoch of 583 BCE was commenced from the birth of King Śālivāhana. “Muhurta-Mārtānda” composed in the year 1493 mentions the epoch of the Śaka era as the birth of King Śālivāhana. Thus, the name of Śālivāhana was linked with the epoch of 583 BCE from the 9th century CE onwards. Since Indians gradually forgot the epoch of the Śaka era (583 BCE), the astronomical epoch of 78 CE has also been referred to as Śālivāhana era considering it as identical with the Śaka era.

Conclusion

The critical and comprehensive study of epigraphic and literary references of the Śaka era leads us to the conclusion that the Śaka era and the Śakānta era are not identical. The epoch of the Śaka era commenced in 583 BCE, whereas the epoch of the Śakānta era commenced in 78 CE. The chronological history of ancient India has been brought forward by 661 years, because these two different epochs have been mistakenly considered as identical. The inscriptions dated in the Śaka era must be segregated into these two epochs carefully for reconstructing the chronology of ancient India. If we consider the epoch of the Śaka era in 583 BCE based on the verifiable details of inscriptions and the revised epochs of various other Indian eras as the sheet anchor for reconstructing the chronology of ancient India, it not only reconciles with the chronology given in Puranas, Buddhist and Jain sources, but also ensures that there is not a single inscription, which can be rejected as “spurious” or “forgery”.

References:

- Indian Antiquary, Volume XXIII, 1894, pp. 113-134; Ibid, Volume XXIV, 1895, pp. 1-17 & 181-211; Ibid, Volume XXV, pp. 266-272 & 289-294, Ibid, Volume XXVI, pp. 146-153.

- Bhaskaracharya, “Siddhanta Siromani”, Ganitadhyaya, Madhyamadhikara, Kalamanadhyaya, Verse 28.

- Chatterjee, Bina, “Sisyadhivriddhidatantra of Lalla” with the commentary of Mallikarjuna Suri, Part I, Indian National Science Academy, 1981, pp. 6.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume XXI, pp. 133-147.

- Indian Antiquary, Volume XVI, pp. 15-24.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume IX, pp. 174-181.

- Sachau, Dr Edward C., “Alberuni’s India”, Rupa Publications India Pvt Ltd, New Delhi, 2002, pp. 409-410.

- http://eclipse.gsfc.Nasa.gov

- Indian Antiquary, Volume VII, pp. 217-220.

- Epigraphia Carnatica, Volume VIII, Sorab Taluq, 71, pp. 22.

- Indian Antiquary, Volume VI, pp. 72-75.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume IX, pp. 98-102.

- Journal of Epigraphical Society of India, Volume 11, 1984, pp. 106-113.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume XIII, pp. 275-282.

- Annual Report of the Mysore Archaeological Department, 1942, pp. 208-231.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume XXVIII, pp. 94-98.

- South Indian Inscriptions, Volume XX, No. 182, pp. 231.

- South Indian Inscriptions, Volume XX, No. 184, pp. 232-233.

- Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume XII, Issue no. 33, pp.1-10.

- South Indian Inscriptions, Volume XV, No. 191, pp. 235.

- Indian Antiquary, Volume XVIII, pp. 128.

- Indian Antiquary, Volume VII, pp. 209-217.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume IX, pp. 200-206.

- Epigraphia Carnatica, Volume IX, Nelamangala Taluq, 61, pp. 51-53.

- The Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society, Volume 14, 1923-24, pp. 82-88.

- Ramesh, KV, “Inscriptions of the Western Gangas”, Agam Prakashan, New Delhi, 1984, pp. 206-216.

- Ibid, pp. 358-368.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume I, pp. 338-346.

- Mirashi, VV, “Inscriptions of the Silaharas”, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Volume VI, 1977, No. 53, pp. 246-249.

- Ibid, No. 54, pp. 250-253.

- Indian Antiquary, July 1888, pp. 205.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume XXXVII, pp. 1-8.

- Varahamihira, “Brihat Samhita”, Chapter 13, Verse 3.

- Epigraphia Carnatica, Vol 3, 1974, Nanjanagudu, No. 342, pp. 400.

- Inscriptions of The Vijayanagara Rulers, Vol I, Part 5, No. 760.

- Annual Report of the Mysore Archaeological Department, 1941, pp. 147-148.

- Yavanajataka of Sphujidhvaja, Chapter 79, Verse 14.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume X, pp. 81-89.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume VIII, pp. 182.

- Indian Antiquary, Volume XII, pp. 156-165.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume IV, pp. 332-348.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume XXIII, pp. 212-222.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume III, pp. 53.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume III, pp. 53-58.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume XXXV, pp. 269.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume VI, pp. 208-213.

- Indian Antiquary, Volume IX, pp. 293-296.

- Annual Report on South Indian Epigraphy, 1939-40 to 1940-42, pp. 20.

- Journal of Bharat Itihas Samshodhan Mandal, Volume III, Part I, pp. 6-16.

- Annual Report on South Indian Epigraphy, 1933-34, pp. 4, No. A2.

- Sources of Medieval History of Deccan (Marathi), Volume II, pp. 23-31.

- Indian Antiquary, Volume IV, pp. 274-278.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume XXV, pp. 199-225.

- Shastri, Ajay Mitra, “Saka era”, Indian Journal of History of Science, 31(1), 1996, pp. 67-88.

- Sachau, Dr. Edward C, “Al Beruni’s India”, Rupa Publications, New Delhi, 2002, pp. 410.

- Madras Journal of Literature and Science, Vol. 7.

- Jyotirvidabharanam,Chapter 10, verse 110-112.

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Vedveer Arya is a civil servant and an officer of 1997 batch of Indian Defence Accounts Service (IDAS). Presently, he is working as Integrated Financial Advisor in Ministry of Defence, Government of India. He earned his master’s degree in Sanskrit from University of Delhi. He is the author of “The chronology of Ancient India: Victim of Concoctions and Distortions”, published in 2015.