Samskrutandhramulu—the word is a Dwandwasamasam, a compound word formed by joining “Samskrutam” and “Andhram.”

Andhram here represents the ‘Telugu’ language. The term Andhra Bhasha was and is often used in Sanskrit to mean Telugu language in the sense that it is the language of Andhra region that includes today’s Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. Many scholars from this region introduced themselves as someone who has made some effort in ‘Samskritandhramulu’. This is to show how the two words beautifully weave together into a Samastapadam and also to make my intention clear in using the word ‘Andhra’.

Telugu is a Dravidian language belonging to the South-central Dravidian group in eminent linguist Sri Bhadriraju Krishnamurthy’s classification. And Sanskrit, is widely acknowledged to belong to the Proto-Indo-Aryan and Proto-Indo-European group. There exists a great ‘commensalism’ between them where Telugu takes a lot from Sanskrit and also lets Sanskrit thrive where it’s the lingua-franca. It is common knowledge that many Indian languages show this phenomenon to varying degrees.

This article tries to make an amateur attempt in showcasing that relationship.

Prakrit Connection

Even after Telugu came out as an independent language, many inscriptions in the region were in Sanskrit and Prakrit. Telugu heavily borrowed from various Prakrits in the initial stages. The semblance between Sanskrit and Telugu came from Prakrits. But later on, it was directly influenced by Sanskrit.

Vedic Traditions

This influence can be attributed to some extent to the strong Vedic traditions in many parts of the united Andhra region which meant that Sanskrit learning was a must.

One of the prominent lawgivers of Grihyasutras that are still followed is Apasthamba who belonged to the Godavari region. Another lawgiver believed to be from this region and more famous for his ‘Sulbasutras’(includes the Pythagorean theorem) was Baudhayana.

Even the legendary exponent of Purva Mimamsa School, Kumarila Bhatta is also believed to be from Andhra by some. Though debatable, there are evidences that he was patronized by the local kings.

Telugu Script and Tatsama

The Telugu script styled itself to suit the pronunciation of Sanskrit ‘mahapranams’(bha, pha, thaetc).

The grammar or meta-language of Telugu is written in Sanskrit. While Adikavi Nannayya started the Mahabharata in Telugu as an attempt to write something in his lingua-franca, it was so Sanskritized that it felt like a Sanskrit work. It had long compounds like Avivekakaranadarunaiswaryavaliptudu’.

Tikkana

Later poets like Tikkana brought more ‘accha (pure/native) Telugu’ vocabulary but Sanskrit remained entrenched. As the use of the vibhaktipratyaya ‘mu’ as in mahabharatamu diminished, Telugu started sounding much more like Sanskrit in pronouncing words from the neuter gender. Soundaryam, Lalityam and many such words of Sanskrit sound as is in Telugu.

Another feature is the use of borrowed words from Sanskrit as it is (tatsama). There are vikritis like ‘Siri’ for ‘Sri,’ ‘Punnami’ for ‘Pournami’ and many words borrowed from Prakrits that sound like Sanskrit words. Words like aggi (agni) and ituka (istika in Sanskrit) are some examples.

But the free flow of Sanskrit tatsamas as is without any change in pronunciation doubled the vocabulary. While Sanskrit-speaking populace diminished in India, it flourished through Telugu and reached a bigger audience.

Scholars in Medieval Times

Medieval periods also witnessed some great Sanskrit scholars from the region like Kolachela Mallinatha Suri who wrote extensive commentaries on Kalidasa’s works. He hailed from the Hyderabad region.

Vidyaranya Swami, author of the popular ‘Madhaviya Sankara Digvijaya’ was from Warangal. Vallabhacharya (of Pushtimarga and author of many works like Madhurashtakam) and Nimbarka had roots in this region.

Bhaskararaya who wrote the commentary on ‘Lalitha Sahasranamam’ was born near present-day Hyderabad. All this shows the continuous flourishing of Sanskrit in the region.

Telugu Literature

The golden age of Telugu literature under the Vijayanagara Empire that saw the Prabandha (loosely: “essay”) style touch its peak was due to the Ashta Diggajas (literally: “Eight Elephants”) of Sri Krishnadevaraya and many of them were from the Rayalaseema region.

It was the scholars of this time who blended Telugu and Sanskrit vocabulary seamlessly in their works. Palkuriki Somanatha who wrote Basava Puranam and many other works in Telugu and Kannada authored several works in Sanskrit.

The heavyweight Srinatha was well known for his chatupadyams (a genre well established in Sanskrit) apart from his kavyas. Another well-known poet whose mention is a must is the beloved Pothanaamatya who wrote the ‘Andhra Maha Bhagavatam’. It contains sweet and simple poems predominantly in Telugu juxtaposed with ones like:

ala vaikuNThapurambulo nagarilo nAmoolasaudhambu dA

pala mandAravAnAntarAmRRitasara:prAntendukAntopalotpala

parya~Nkaramavinodiyagu ApannaprasannunDu

vihwalanAgendramu pAhipAhi yana guyyAlinchi saMrambhi yai.

अल वैकुण्ठपुरम्बुलो नगरिलो नामूलसौधम्बु दा

पल मन्दारवानान्तरामृतसर:प्रान्तेन्दुकान्तोपलोत्पल

पर्यङ्करमविनोदियगु आपन्नप्रसन्नुन्डु

विह्वलनागेन्द्रमु पाहिपाहि यन गुय्यालिन्चि संरम्भि यै।

Note the long samasa to describe Vishnu in the second line in bold.

Sanskritized Telugu was—in today’s parlance—elitist to a great extent. But there were many successful attempts to take it to the masses. These were necessitated by the historical turn of events like the Bhakti movement.

Shatakams

After the fall of the mighty Vijayanagara Empire, the vacuum created by the lack of royal patronage for classical poetry now fell on small feudal lords.

Equally, the Bhakti movement and many other factors now contributed to literature, which diluted the classical so that they could be understood by commoners. This is where the Shataka Sahityam (a collection of hundred verses) comes in. Modeled on the Samskrita Sataka genre, this grew to become immensely popular. It is said that there are hundreds of Shatakams (if not thousands) in Telugu. There were no strict rules except adherence to metre in this genre. Palkuriki Somanatha’s ‘Vrishadhipa Shatakam’ and Baddena’s ‘Sumati Shatakam’ are considered the earliest. Poems from Sumati Shatakam are widely used even today.

Sculpture of Vemana

The great Vemana too wrote his Vemana Satakam in simple Telugu mixed with Sanskrit vocabulary. Dhurjati in his Kalahasteeswara Shatakam brought more sophistication. In Narasimha Shatakam, the flag or refrain is ‘Dushta Samhara Narasimha Duritadoora!’

An example from Krishna Satakam-

nArAyaNa parameshwara

dhArAdhara nIladeha dAnavavairii!

kSheerabdhishayana yadukula

veera, nanugAvu karunavelayaga kRRiShNa!!

नारायण परमेश्वर

धाराधर नीलदेह दानववैरी!

क्षीरब्धिशयन यदुकुल

वीर, ननुगावु करुनवेलयग कृष्ण!!

Indeed, many Telugu people who know this popular shloka wouldn’t know that the poem makes extensive use of Sanskrit words. That was the level of assimilation of Sanskrit in Telugu.

Kuchipudi

The other art form that took Sanskritized Telugu to the masses was the Kuchipudi dance. It was a very popular dance form and permeated the entire Andhra society. The Bhagavatulu (dance teachers and performers) went to the nook and corner of the Andhra country and performed for the masses. Also known as the Bhagavatamelam and having roots in Bhakti movement, it has many Yakshaganas like Prahlada Charitra, Usha Parinayam rich in Sanskrit vocabulary. To perform the Golla Kalapam where an ordinary Gollabhama (cowgirl) teaches the secrets of Vedanta to a learned Brahmin, one would have to learn the five kavyas, Vedanta Granthas and many more in Sanskrit. The most loved and performed piece of Kuchipudi is the Bhamakalapam. Authored by Siddhendrayogi as a showcase of Madhura Bhakti (tender devotion), this work has a unique passage where the lovelorn Satyabhama writes a letter to SriKrishna.

shrImadRatnAkaraputrikAmukhAravindamarandapAnavilolamilindAyamAna!

nandanandana, muchukundavarada, mandaroddhara, parihasitaraakaasudhAkara

sundaravadanAravinduDagu shrIrAjagopalaswAmivAricharanAravindamulaku

satyabhAma nitalataTaghatikarakamalayai sAyangala vinnapamulu!!

श्रीमद्ऱत्नाकरपुत्रिकामुखारविन्दमरन्दपानविलोलमिलिन्दायमान!

नन्दनन्दन, मुचुकुन्दवरद, मन्दरोद्धर, परिहसितराकासुधाकर

सुन्दरवदनारविन्दुडगु श्रीराजगोपलस्वामिवारिचरनारविन्दमुलकु

सत्यभाम नितलतटघतिकरकमलयै सायन्गल विन्नपमुलु!!

A Kuchipudi performance

Video link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3BitJ_LBRU8 (The abhinaya or performance for this poem starts at 3:00). Note the first line. It is one long compound word describing Krishna. Smt. Shobha Naidu says in that video that this padyam is in ‘chakkati (nice) Telugu’!! While the only Telugu we see is in the last two words and the prepositions.

Sri Narayana Teertha’s tarangams from his musical opera,‘SriKrishna Leela Tarangini’ in Sanskrit formed an integral part of the Kuchipudi repertoire.

An offshoot of this dance form is the Melattur Bhagavata Mela tradition that still exists in the Tanjavur district of Tamil Nadu and consists of Sanskrit and Telugu.

Sankeerthanams

Another famed aspect of Telugu literature that brought Sanskrit to the masses is the SankeertanaSahityam (devotional literature).

Sri Tallapaka Annamacharya heralded this tradition by composing in chaste Telugu and pure Sanskrit (for example, Bhavayamigopalabalam etc) and a mix of both. Bhadrachala Ramadasu did the same. When he says ‘Sharanagatatranabirudankitudavu’ in the krithi ‘palukebangaaramaayena’ it’s often considered as Telugu. Many Telugu scholars who were equally proficient in Sanskrit moved to the Tanjavur region where they found patrons in the Nayaka rulers. Sadasivabrahmendra was born into a Telugu family and composed krithis in Sanskrit. Tyagaraja Swami wrote many krithis in simple Telugu laden with Sanskrit. His ‘Jagadananda karaka’ has 108 adjectives of Lord Rama all in Sanskrit.

Another example is ‘Varaleelaganalola’ modeled on a tune of British bands of that time. This is completely in Sanskrit but can easily passed off as Telugu. Even in his Telugu krithis, we can see simple but long Sanskrit compounds like ‘amitaparakramadyumanikularnavavimalachandruni’.

That brings us to the 19th century where the first Telugu novel came into being in the form of Rajasekhara Charitra (inspired by The Vicar of Wakefield), written by Sri Kandukuri Veereshalingam Pantulu. This age also witnessed the revival of Avadhanams, Harikathas and Natakams (drama). It was truly a renaissance era period in Telugu literature.

Harikatha (Literally: Story of Lord Hari or Vishnu)

Sri Ajjada Adibhatla Narayana Dasu was a genius who can be considered as the renaissance man of Telugu. He wrote and performed many Harikathas in Sanskrit and Telugu, authored many books in Sanskrit, was proficient in music(he could play five instruments at a time) and performed many Avadhanams.

Telugu Harikathas had great following in rural areas. More on him here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ajjada_Adibhatla_Narayana_Dasu

Avadhanam

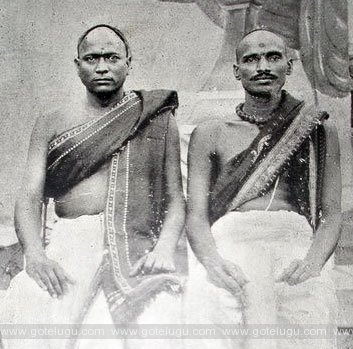

The art of Avadhanam (Avadhana Kala) in both Sanskrit and Telugu was revived by the immortal poet-duo Tirupathi-Venkatakavulu (Diwakarla Tirupathi Sastri and Chellapilla Venkata Sastri) in the early 20th century.

Tirupathi-Venkatakavulu

They went from one samsthanam (provinciality) to the other performing Avadhanams and earned great accolades. Their Avadhanams are full of great spontaneous padyams, loaded with Sanskrit.

Later on, many scholars performed great feats in Telugu Avadhanams.

The region has many Avadhanis in Sanskrit too, like the eminent scholars Sri Dorbala Prabhakara Sarma and Sri Chirravuri Srirama Sarma.

Drama

No other art form can compare with the Natakams when it comes to taking credit for the propagation of Sanskrit and creating a love for language and vocabulary in the Telugu consciousness.

Dramas like Harischandra, SriKrishna Rayabharam (by Tirupathi-Venkata duo), Chintamani and several others were great crowd pullers. Their appeal cuts across caste and social barriers. The padyams (poems) in these Natakams are noted for extensive usage of simple Sanskrit and were immensely popular.

Let’s see a sample from SriKrishna Rayabharam:

JenDApai kapirAju mundu sitavAjishreNi yun gUrchi ne

danDambun goni tolu syandanamu meedan naari sArinchuchun

GAnDIvambu dharinchi phalguNuDu mUkan chenDuchunnapuDu

okkaDun nI mora naalakimpaDu kurukShmAnAtha sandhimpagan

ज़ेन्डापै कपिराजु मुन्दु सितवाजिश्रेणि युन् गूर्चि ने

दन्डम्बुन् गोनि तोलु स्यन्दनमु मीदन् नारि सारिन्चुचुन् |

ग़ान्डीवम्बु धरिन्चि फल्गुणुडु मूकन् चेन्डुचुन्नपुडु

ओक्कडुन् नी मोर नालकिम्पडु कुरुक्ष्मानाथ सन्धिम्पगन् ||

It was a common sight to see the dramas extending up to the wee hours of the morning because of people demanding encores of these padyams.

Films

This love of mythological drama spilled into films as many of the artists hailed from the theater background. And producers too,knew that this genre would sell.

The result is that there are innumerable, topnotch mythological movies in Telugu that are full of padyams. Sanskrit finds a big place in film songs as well.

When Sri Veturi Sundararama Murthy wrote “Sankaragalanigalamu Sriharipadakamalamu Ragaratnamalikataralamu Sankarabharanamu”, people would mostly reach out to the dictionary only for the word ‘taralam’ which means ‘central gem in a necklace.’

Another lyric, almost completely in Sanskrit from a hugely successful commercial movie.

Induvadana Kundaradana Mandagamana Madhuravachana Gaganajaghanasogasulalanave.

Usage of Sanskrit cuts across religion. Many songs in Christianity in (united) Andhra use a lot of Sanskrit vocabulary. The great poet Gurram Jashua wrote the Kristu Charitra in Telugu.

Indeed, even left-wing literary movements in the state had no qualms using Sanskrit when naming their organizations Arasam and Virasam (Acronyms for Abhyudaya/Viplava Rachayitala Sangham). The most notable poet of that genre Sri Sri, composed ‘Mahaprasthanam’.

Sanskrit also finds a big place in proverbs (samethalu), nudikaramulu (nyaya/lokokti) and day-to-day usage. For example,

Sandarbhochitamugamaatladu (speak in a way that’s apt to the context)

Antyanishturamkannaadinishturammelu (animosity in the beginning is better than at then end)

Shatakotidaridralakuanantakotiupayalu (infinite crore solutions for hundred crore problems)

Aagarbhasrimantudu (rich by birth, born with a silver spoon)

Nayanaanandakaram (delight to the eyes)

Gomukhavyaghram(cow-faced tiger) is equally popular though the equivalent ‘mekavannepuli’ exists.

Aamulagram, nakhashikhaparyantam (end to end)

Sakalammukulam (fold everything and sit) – used in Telangana region for saying ‘sit cross-legged and with folded hands’

Vinayavidheyatalu (humility and sincerity)

Alasyatamrutamvisham (laziness converts even ambrosia to poison)

Niraksharakukshi (illiterate)

Students who study in Telugu as a medium of instruction and are still very high in number are familiar with many technical terms coined through Sanskrit like ‘Seetoshnasthiti’ and ‘ushnograta’.

Although English is increasingly used while speaking Telugu these days, Sanskrit still holds its place. The linguist Prof. Velcheru Narayana Rao rightly said, ‘Every Sanskrit word is potentially a Telugu word’.

May this symphony continue and prosper.