In India we increasingly celebrate the New Year according to the Gregorian calendar, named after Pope Gregory, who instituted it. A Calendar has scientific, social and cultural significance. Other than synchronizing activity it is also used in every day life as a marker of seasons. A scientific calendar would both be an accurate predictor of seasons as well as be aligned with the cultural and social aspect of people. Is the Gregorian calendar scientific and appropriate for India, or are we celebrating the wrong New Year’s Day?

All major civilizations follow their own calendar and celebrate their own New Year’s day. The Chinese New Year is a huge social and national celebration of great traditional significance. Similarly Islamic countries mark their calendar from Hijrih New Year per the Muslim Calendar. Israel celebrates Rosh Hashanah marking the beginning of the New year. Western Countries follow the Gregorian calendar. The New Year in this calendar is first traced to the Roman New Year and then to Pope Gregory’s linking it to the Feast of Circumcision, the eighth day after “Jesus’s Birth.”

Similarly, the years of the Gregorian Calendar are aligned with the belief that the world changed with the advent of Jesus Christ (hence “BC” and “AD” secularized into BCE and ACE now). “Secular” India, as in many other things, follows the Christian calendar as the official one.

Religious beliefs may be what they are, but could we have a scientific basis for a calendar instead? Is this Gregorian/Christian calendar better and more scientific than the Indian ones? Calendars matter as they affect daily life. One noticeable aspect of the Gregorian calendar is that it is a solar calendar that ignores the phases of the moon, unlike the Hindu calendars. The latter are also sidereal, taking into account he position of the sun relative to the stars. How does this matter?

Many years ago I was visiting a friend Pawan Gupta, in Musoorie. He had moved to the area after his graduation from IIT Kanpur to serve and educate rural people. He recounted many incidents where he ended up learning instead, and one stood in my mind.

He noticed that the villagers would align their sowing and harvesting with the festivals according to the Hindu calendar. He dismissed this is superstition, till he made a remarkable discovery. The insect lifecycle was also aligned to the “Hindu calendar” since the latter followed lunar months. Insect fertility patterns were perhaps affected by the availability of light or by possible hormonal changes. The lunar calendar aligned harvesting so that it would take place right before the big crop of insects would appear. This allowed cultivation with less pesticide use. Many scientific studies have now begun to trace tracing the effects of the lunar cycle on plants, animals and possibly even humans.

The Calendar also is a predictor of seasons. In India, which remains primarily agricultural, the correct prediction of the monsoon rains is of utmost importance. As the brilliant mathematician C K Raju points out, the Gregorian Calendar may also be failing us in this regard. Often times we say the monsoon is “early” or “late” according to the Gregorian calendar, but the Indian calendar systems may be predicting the seasons more accurately. The Indian calendar uses the sidereal system, which also tracks the position of the sun relative to the stars, not just the position of the earth with respect to the sun. He notes, in “Could India’s “Failed” Monsoon Have Been Predicted by the Right Calendar?” using a particular example:

“At any rate, the monsoons have arrived on time according to the Indian calendar, since Rakhi too was “very late” this time, and the current month is still Srâvana. (The calendar we are talking about was calibrated for Ujjain, about 150 km from Bhopal.) The monsoons, however, are delayed by a month according to the Gregorian calendar: or, to put it differently, the Gregorian calendar has given the time of the monsoons in a grossly incorrect way. If the monsoons depend only on the tropical year, then, because of the difference between the tropical and the sidereal year, it is the Indian calendar that ought to have been out of phase by three weeks (around 21 days).”

He hypothesizes that this may indeed by relating to the accuracy of India’s sidereal Calendar, advocating further scientific study of this phenomenon:

“The monsoons, thus, depend also upon the Coriolis force. The Coriolis force is an inertial force. The only possible inertial frame being a frame fixed relative to the distant stars, the Coriolis force hence relates to the sidereal motion of the earth. Thus it might be that the monsoons relate also to the sidereal year.’

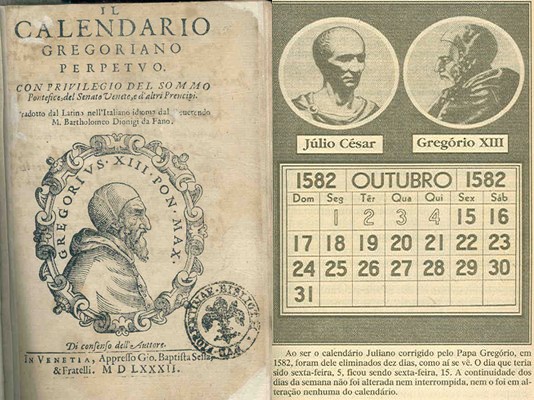

It is worth noting that the Gregorian calendar itself is an attempt to fix up the earlier Christian calendar, which was the Julian calendar. As a result of these errors, the Europeans were having severe problems in navigation and the Pope dispatched a team of Jesuits to India to learn the Calendar Systems. (This also related to the transmission of the differential Calculus from India to Europe that Raju has documented elsewhere). But, as is often the case in copying, the Gregorian calendar does not appear to have reached the accuracy of the original Indian calendar in its scientific predictive abilities.

Yes, we persist with the Christian Gregorian Calendar as “modern” and scientific without much analysis or debate. This calendar is neither scientific nor culturally attuned to our festivals and celebrations. Excluding the moon, it also excludes our relationship to the feminine aspect of nature, much as Christianity denied the feminine. Female menstrual cycles also have been found to have a relation with the moon in recent scientific studies.

Our dissociation with the lunar cycles is also a dissociation from nature in secular modernity, itself an outgrowth of Christian theology. It is time to move from a religiously-based patriarchal Gregorian calendar to a truly modern and scientific one, not one based on “Jesus” but on cosmic events of scientific significance. For India the Gregorian calendar is neither culturally nor scientifically relevant, and neither is its associated “New Year’s Day”.

Sankrant Sanu is an entrepreneur, author and researcher based in Seattle and Gurgaon. His essays in the book “Invading the Sacred” contested Western academic writing on Hinduism. He is a graduate of IIT Kanpur and the University of Texas and holds six technology patents. His latest book is “The English Medium Myth.” He blogs at sankrant.org .