“India is an old country, but a young nation; and like the young everywhere, we are impatient. I am young and I too have a dream. I dream of an India, strong, independent, self-reliant and in the forefront of the front ranks of the nations of the world in the service of mankind.” (Full Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VOJO3s3n51M )

With these words delivered before US Congress in Washington during the summer of 1985, Rajiv Gandhi, not only spelt out his vision for India but also signalled the arrival of a Confident India.

The warmth and confidence Rajiv Gandhi was oozing much through 1985, had its genesis in the winter chill of December 1984. On 29 Dec precisely, the day when the Election Commission started announcing the historic results of the 1984 General Elections. Riding a sympathy wave following his mother’s assassination, Rajiv Gandhi demolished the opposition by winning 404 seats out of 514. The tally was increased by another 10 seats following delayed elections in Punjab and Assam.

Such was the ferocity of this mandate that the closest opposition of Congress was the Telugu Desam Party, a regional party with 30 seats. The current ruling party, the BJP could win only two seats. Little did it know then that it will have much to thank Rajiv for, for its dramatic rise through the late 80’s and 90’s— a rise that would establish the BJP as an important pole of Indian polity— to eventually giving it a pole position in May 2014, riding positive on the Narendra Modi wave.

Such was the ferocity of this mandate that the closest opposition of Congress was the Telugu Desam Party, a regional party with 30 seats. The current ruling party, the BJP could win only two seats. Little did it know then that it will have much to thank Rajiv for, for its dramatic rise through the late 80’s and 90’s— a rise that would establish the BJP as an important pole of Indian polity— to eventually giving it a pole position in May 2014, riding positive on the Narendra Modi wave.

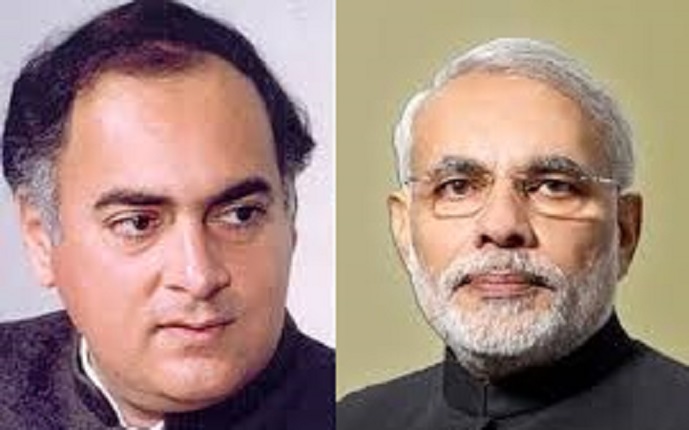

The Modi government is the first majority government to assume power in Delhi after Rajiv’s brute majority of 1984. Analysing Rajiv’s tenure is thus essential to develop a template of “things to avoid” to stop history from repeating itself in 2019.

Right slogans, Youthful Cabinet and Promise of Change

Although, the Congress had not fought the 1984 elections on any reform agenda, Rajiv Gandhi began his rule on an extremely positive, reformist note, promising a strict monitoring of ministerial performance and vowing to fire those who don’t deliver. More than two thirds of his 39-member cabinet had ministerial experience of less than five years, thus earning it the title of the most youthful cabinet.

With the right slogans and comments such as “of every 1 rupee spent on the poor, only 15 paisa reaches them”, he went on building his image as the “Mr Clean” of Indian politics. A large number of Indians began to see in him a man who would deliver “change.” Many saw him as an idealist, an anti-politician unwilling to sacrifice for earning short term political capital.

Instead, he was seen as a modernist leader with long-term vision, also fuelled by a cliché of “preparing India for the challenges of 21st century,” almost 16 years in advance. A good-looking face did not hurt either. Mr Khushwant Singh called him “the handsomest Prime Minister in the world.” Rajiv Gandhi was a man in hurry. Buoyed by a historical mandate, he went about taking on everyone — from the babudom to the old guard of his own political party.

He talked of a lean government and decentralisation and instructed his Secretaries and Ministerial colleagues to ensure that files terminate at their level as against the then norm of moving in a circuitous fashion. He believed in quick solutions and thus carved out separate departments— human resources, urban planning, water management and internal security— for increased focus and attention. Rajiv’s missionary zeal, personal charisma and warmth began to attract talented non-political people, mostly “Doscos”, (Doon School alumni) who became his most trusted allies.

Troika and reform push

With the help of troika of VP Singh, Arun Singh and Arun Nehru, Rajiv Gandhi began working on the modernisation and liberalisation of India. In order to dismantle the status-quoist “chalta hai” government apparatus, he superseded various secretaries and built a team of loyal babus cum man-Fridays. Rajiv’s Finance Minister—VP Singh, with an image of honesty and personal integrity—began working on the opening up of the economy, groundwork for which was readily available in the reports of various committees.

One such report was the Dagli Committee Report on the Controls and Subsidies of 1979 (constituted by the much-maligned Janata Government and regarded by many as the finest report, contents whereof, later became the template of the reform agenda of succeeding governments in India). Mr. Singh also implemented some of the recommendations of PC Alexander Committee Report on Import-Export policy and Abid Hussain Committee report on Trade policies— to promote trade and provide the East Asia type export incentives, imports under OGL route and also the time-bound three years’ EXIM (export-import) policy.

These reforms in the external sector of the economy, added by steps to reform the domestic economy, began to show positive results quite rapidly. Mr Singh also slashed tax rates and improved tax administration, both leading to significant rise in tax revenue collection.

Reform measures initiated by Rajiv’s Finance Minister, although implemented in steps, began to drive the wheel of economy forward at much faster pace than the previously slow “Nehruvian Rate of Socialist Growth”. Some of Rajiv’s reformist moves later found place in the core prescription of John Williamson— “Washington Consensus”, a term which advocated the need for a shift in Economy Policymaking.

However, it was Mr. Singh’s offensive against corrupt businessmen and tax evaders — the first-ever concerted effort in post-independence history—that made for staple news in 1985-86. Many leading business houses of the country were targets of raids. Giant businessmen such as L M Thapar and even an elderly and ailing S L Kirloskar were put behind bars for their alleged tax crimes.

However, it was Mr. Singh’s offensive against corrupt businessmen and tax evaders — the first-ever concerted effort in post-independence history—that made for staple news in 1985-86. Many leading business houses of the country were targets of raids. Giant businessmen such as L M Thapar and even an elderly and ailing S L Kirloskar were put behind bars for their alleged tax crimes.

Singh’s backing of his honest officers became the talk of the town and he vowed to bring back the illegal wealth stashed abroad. His efforts on the tax front provided the government with enough money to support its planned investments. The foreign exchange situation also became manageable and India was put on a higher growth trajectory of five per cent (vs the perennial two-three per cent growth rate of the past).

During the V.P. Singh days in North Block, the only indicator that bucked the positive growth trend was inflation that remained subdued and rightly so. Amidst higher economic growth rates, Singh’s own popularity—and ambition—began to soar as well. Meanwhile, pressure had started to show up elsewhere.

Foreign Policy Push and Blunders

As the economy began to stabilise, Rajiv Gandhi turned his focus on the external image of India and began a series of engagements with foreign governments. His whirlwind tours took him to several countries including the US, China, USSR, etc. He used to visit more than one capital during his foreign tours. His 1985 visit to America is regarded as one of the most important ones during his tenure.

He reached out to neighbours and also pressed upon the need for Universal Nuclear disarmament. His foreign visits—an object of fun and ridicule back home—were projected as tools to hardsell India as a preferred destination for much-needed foreign capital and technology.

All along, his administration continued working on maintaining and improving our conventional war superiority over Pakistan. It was during his tenure that General Sunderji famously talked about preparing Indian Army for facing two simultaneous wars on either fronts. One of the biggest war games ever, Operation Brasstacks, was conducted during the Rajiv Gandhi era.

He also approved the “Operation Flowers are Blooming” to help avert a coup in Seychelles and also sent combat troops to Maldives in support of President Gayoom and to Sri Lanka to take on the LTTE. The operation to place our forces at the highest peaks in Siachen was also sanctioned during his tenure.

Reform measures in Other Areas

To curb political corruption, Rajiv government passed an Anti-Defection Law. Several other landmark legislations were also passed by his government, the three-tier Panchayati Raj system, being one of the most important measures.

In order to bolster internal security, his government signed pacts in Punjab, Assam and Mizoram and elections were held in Punjab.The Rajiv government announced the Second National Policy on Education in 1986, both to remove educational disparities and ensure opportunities for all.

Betting on technology as a tool to bring about change, his government launched Sam Pitroda’s C-DoT telecommunication revolution. Under Pitroda’s leadership, five more technology missions in the area of water, literacy, immunisation, oilseeds and dairy were launched. Another key initiative of the Rajiv Gandhi government was the Ganga Action Plan to clean Ganga and its tributaries.

Electronic media saw an unprecedented expansion in coverage and the arrival of private content producers. Apna Utsav and Festival of India, the platforms to showcase India’s cultural heritage to the domestic and international audiences respectively were launched with much fanfare.

The Journey Downhill

Rajiv Gandhi did everything that he considered right and yet his popularity began to decline as his government approached the second year finish line.

His over-dependence on the troika meant that they were getting all the credit for success and good work but blame for failures of others fell only on Rajiv Gandhi. The total concentration of power in the PMO cut him off from both ministerial colleagues and party, as also sentiments of the general public.

The sense of urgency and purpose that he showed in his governance began to disappear and frustration set in. His failure to come to terms with complex issues that a large and diverse nation like India regularly throws up, affected both, his image and popularity.

The babudom that he took on via several supersessions began to strike back and so did the Congress old guard. His self-evaluation led him to accept his failures, albeit in private. The disappointment arising out of failure to bring about the promised changes led him to make peace with the Congress party’s conventional political setup and time-tested vote-bank politics.

VP Singh, Arun Nehru and Arun Singh, Rajiv Gandhi’s biggest change agents and his most competent ministers were projected as his adversaries. The shenanigans of the conventional neta-babu complex, amply helped by an inexperienced and increasingly paranoid leader, then led to their removal from Rajiv’s inner circle and eventually from the government and party itself. Rajiv’s troika, with the exception of Arun Singh went on to become the pivot and the opposition began to rally around them.

What Went Wrong?

The electoral reverses, the Shah Bano issue, Sri Lanka mess etc, added more fuel to the already burning fire that V P Singh had lit with the Bofors Scandal forced Rajiv Gandhi to become one of the very tribe of politicians he had previously bashed.

The system that he wanted to change ended up changing Rajiv Gandhi himself and eventually Rajiv himself became the system. All efforts to set the new course of country’s political agenda came to naught. After that, it was as if misfortune had permanently set in: Rajiv Gandhi kept faltering almost at every step and about every issue and problem. He found new faith in Nehruvian Socialism that he had spoken so much against.

The reform process was stalled. Populist policies – acceptance of pay commission recommendations, rising subsidies – led to higher expenditure; larger government deficits and rising foreign debt began to strain the economy. In the political domain, ministers were changed at the drop of the hat—23 reshuffles in 38 months—making Prabhu Chawla call Rajiv’s cabinet “wheel of confusion”.

Congress CMs were changed across the states and Opposition governments were summarily dismissed. He went back to the politics of the past and wasted the historical opportunity offered by the Shah Bano verdict to implement reforms like the Uniform Civil Code. The dangerous cocktail of the tyranny of legislative prowess and traditional vote-bank politics of Congress were proving to be his nemesis- a fact that he was not ready to accept.

Meanwhile, Rajiv’s external image also suffered as neighbouring nations became increasingly wary of India’s big brotherly attitude. Punjab was already on the boil with no sign of abatement in violence and Kashmir too began to drift away, thanks to extensively rigged J&K elections of 1987.

As Rajiv faltered at every step, his opposition kept growing from strength to strength and became more vocal and fierce. Indecision became the order of the day, key appointments were not made as power was concentrated in an oversized PMO consisting of officials and politicos working at cross purposes with each other. Most of the information that Rajiv was getting was heavily filtered, and the PMO coterie worked to restrict, if not prevent, any exposure to alternate views.

Another failure was his excessive dependence on the supposed magic of technology as an agent of change and a firm belief that various technology missions launched by him would change the lives of the common man. People were seen as objects of change and not the driving force behind the change. His election mandate was interpreted as a plea for populism by the people when all they were looking for were channels to manage their rising aspirations and ways and means to meet the same.

Rajiv Gandhi’s fault was that by spoken words and promises, he let the genie of aspirations out of the bottle but did not know that genie’s journey was now irreversible. He had only two options: keep the genie happy or the push the genie back in the bottle which would end his regime: as it did in 1989. The Congress crashed to 197 seats.

Why Analyse Rajiv Gandhi Now?

History has repeated itself, albeit in a different measure, when Narendra Modi registered electoral success that gave him a full majority, the first in 30 years after that famous Rajiv victory of 1984. The genie that came out reposed its faith yet again, this time in Narendra Modi.

The way Narendra Modi began and the hope that he generated amongst Indians reminds one of the days of Rajiv Gandhi. He is being seen as a change agent, the final outcome of which will be known only by 2019.

The way Narendra Modi began and the hope that he generated amongst Indians reminds one of the days of Rajiv Gandhi. He is being seen as a change agent, the final outcome of which will be known only by 2019.

For now, the bad news is that the comparison between the political trajectory of Rajiv Gandhi Raj and Narendra Modi Raj is eerily similar. But the good news is that Modi still has three plus years on his side and his popularity are largely intact. He also has an administrative experience of 15 years, which can be both a positive and negative.

Although the performance outcome of Modi’s government will only be known by 2019, I am willing to place my bets on him being successful in making the genie dance. For me, it’s not only a hope but a wish as well.

(With inputs from AS Raghunath)

The author is a Chartered Accountant by qualification. He is the founder of the adventure tourism venture, Nature Connect Outdoors. Alok has a keen interest in politics and economic development.