As a new Gregorian year begins, it is appropriate to revisit the concept of a welfare state in the Sanskrit canon. The state had its obligations to the broader population. The public welfare was the measure by which a state was assessed. Kautilya authored the Arthashastra – a Sanskrit literary classic on statecraft – in the 3rd century BCE. I relied on L.N. Rangarajan, “Kautilya: The Arthashastra: Edited, Rearranged, Translated and Introduced,” Delhi, Penguin Publication, 1992 for this piece.

The Arthashastra emphasized (i) public administration; (ii) economic prosperity; (iii) social welfare; (iv) effective diplomacy; and (v) military preparedness as essential ingredients of a successful state. A capable ruler had to focus on these five elements. I will limit myself to the subject of public welfare.

This 2,200 year old Sanskrit document defined welfare as

the increase in economic activity, the protection of livelihood, safeguarding vulnerable segments of society, consumer protection, the prevention of the harassment of citizens, and the welfare of labour and of prisoners.

Kautilya begins his text by mentioning that

In the happiness of his population, rests the ruler’s own happiness, in their welfare lies his welfare, he shall not necessarily consider as good whatever pleases him but he shall consider as good whatever pleases his population.

Kautilya proceeds to define the ideal ruler as one “who is ever active in promoting the welfare of the people, and who endears himself by enriching the public and doing good to them.”

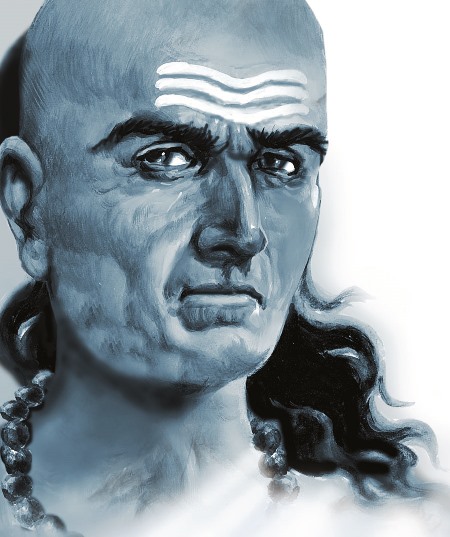

The vast empire founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 321 BCE was administered by an efficient bureaucracy. It had an excellent communications network and came under the control of a strong ruler. Kautilya was the King’s chief advisor and strategist. The Arthashastra provided a political philosophy to unify previously small political units, weld divergent groups into a broader cohesive identity and integrate diverse linguistic groups. The emphasis on the common weal was intended to cement a diverse and heterogeneous population. The end goal was social cohesion.

This explains the continued relevance of several of the administrative principles enunciated in this classical text. This Sanskrit document influenced political theory and traditional statecraft in India, Nepal and in the Hinduized states of classical-era South East Asia down the centuries.

References to the welfare state in the Arthashastra are vast. I will confine this discussion to the prevention of public extortion, the welfare of public officials and the welfare of prisoners.

Kautilya begins by defining public harassment to include (a) village officials who extort; (b) heads of departments who are corrupt; (c) judges who solicit bribes; (d) counterfeiters; (e) traders who cheat the public; and (f) military personnel who go on rampage. The Arthashastra suggests mechanisms to enable the public to routinely register their complaints; to facilitate the investigation of such complaints; and to provide compensation where called for. Punishments for corrupt officials and traders are prescribed.

The Arthashastra defines the vulnerable segments of the population to include “minors, the aged, the sick, the disabled, the insane, Brahmins and ascetics.” The vulnerable “are to enjoy priority of audience before the king, maintenance at state expense, free travel on ferries and given special consideration by judges.”

Village elders were to hold the property of orphans in trust and look after them. The state had to maintain destitute children, the aged, childless women and the helpless. The Arthashastra emphasizes that “when an enemy fort was attacked, non-combatants, those who surrender and the frightened were not to be harmed.”

More importantly, Kautilya provides for the protection of female labor from exploitation. It stipulates harsh punishment for rape. It emphasizes the protection of commercial sex workers from physical injury and exploitation.

In the section on the rights of prisoners, the Arthashastra emphasizes the need for “(i) separate prisons for men and women; (ii) the provision of adequate halls, water wells, bathrooms and latrines; (iii) protection of prisoners from fire hazards and poisonous insects; and (iv) safeguarding the rights of prisoners in their daily activities such as eating, sleeping and exercise.” Kautilya restricts warders from torturing prisoners and prescribes severe punishments for the rape of female prisoners. He advocates the periodic release of prisoners on general amnesty.

The Arthashastra recommends that “Those officials who do not eat up the state’s wealth but increase it in a just manner and are loyally devoted to the state shall be made permanent in service.” He adds that “an official who accomplishes a task as ordered or better shall be honored with a promotion and rewards…The state is to provide for the family of a government servant who died on duty.”

Meanwhile, women had the right to inherit and transfer property. The Arthashastra also states that the ‘third gender’/homosexuals should be maintained by their families as they lack children and therefore do not inherit property. It forbids the vilification of the ‘third gender’.

Many of these precepts are modern in outlook and resonate with a contemporary audience. It is important to note however that it often only represented theory and the ideal. The actual practice of statecraft through the centuries did not necessarily meet these high standards. Further, Kautilya urged rulers to ruthlessly crush dissent and political opposition. His was not always a humane text in its anticipation of the Machiavellian ethos. Moreover, several other principles of the Arthashastra are irrelevant today.

Nevertheless, the text continues to provide an archetype of political thought that defines Hindu political theory, much like Plato’s Republic did in Europe. It’s time to revisit it as we judge the effectiveness of our contemporary political systems. There are other chapters on trade, public finance and economic enterprise. But that discussion later.

‘Dr. Naresha Duraiswamy is a Sri Lankan national. He received his doctorate in International Relations at Columbia University. His writes on Hindu civilization and public life with a focus on law, economics, statecraft and sociology.