It was gratifying to see the heartwarming story of Sridhara Ayyaval in modern media.

The article in question was written by Indic scholar Shri Aravindan Neelakandan and focused on a famous incident in the seer’s life, the appearance of the Ganga in the well in his backyard at Tiruvisainallur. The article placed the incident as an act of defiance against orthodoxy and the appearance of the Ganga as divine approval of humanitarian impulses over orthodoxy.

This characterization is troublesome, since it depicts a seeming conflict between adherence to shastras and human empathy. This devalues the critical position of orthodoxy/orthopraxy in Hinduism, both the ‘Brahminical’ shastric variety and the native traditions of cultivators, herders, forest dwellers, fisher-folk and assorted tradespeople, all of whom have rigorous ritualistic cultures.

However, if we frame this incident in terms of a dharmic dialogue between Sridhara Ayyaval and the other residents of his agraharam, on a subtle point of shastric interpretation, the issue raised resolves itself.

Sridhara Ayyaval and His life

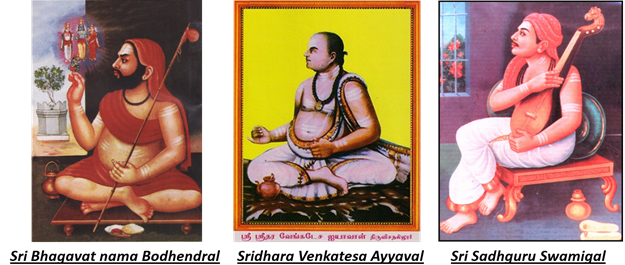

For people outside the sphere of influence of the bhajana and nama sankirtana sampradaya of Tamil Nadu, Sridhara Ayyaval is an unknown name. Along with Bhagavat Nama Bodhendral (Bodhendra Sarasvathi of the Kanchi Mutt) of Govindapuram and Marudanallur Sadhguru Swamigal, he forms the Trinity of founders of the nama sankirtana sampradaya specific to Tamil Nadu and especially the central Thanjavur Region.

Sridhara Ayyaval’s influence reaches up to modern times, through nama sankirtana exponents such as Gopalakrishna Bhagavatar. The enduring popularity and vitality of the nama sankirtana movement is evidenced to this day by bhajana superstars such as Jayakrishna Dikshitar (Vittaldas Maharaj) and Vishakha Hari. Sridhara Ayyaval was known to have been among the group of scholars settled in the hamlet of Tiruvisanallur by Raja Shahaji Bhosale of Thanjavur.

The hamlet of Tiruvisainallur – A rural academe

During the reign of Shahuji Bhosale I of Thanjavur, he established the Brahmadeya agraharam of Shahajirajapuram, with a group of 40-50 scholars. Among these were the grammarian and dramatist, Ramabhadra Dikshita, various accomplished ritualists and logicians.

Sridhara Ayyaval was the son of Sridhara Lingarayar, one of the original groups settled in Tiruvisainallur.

This was a period of heightened creative and spiritual activity in the Thanjavur region. Sadasiva Brahmendra Sarasvati, Bodhendra Sarasvati and Sridhara Ayyaval were roughly contemporaneous.

Thus, it is without doubt that the residents of Tiruvisainallur at the time of Ayyaval were hardly hide-bound frogs in the well. One can imagine regular scholarly discussions on finer points of vyakarana, nyaya, itihasa, vedas, mimamsa and assorted shastras. This incident in Ayyaval’s life would have been a high point among such discussions and debates.

Humanitarian impulse – Where do the shastras stand?

Coming to the incident in question, the facts commonly known are that Ayyaval was getting food prepared for a shraddha ceremony at his home. For the uninformed, this involves inviting a minimum of two Brahmanas, one as an embodiment of one’s ancestors and the other as an embodiment of the Gods. These two Brahmanas are served food, after the annual shraddha sacrifice is performed.

The rules for this ritual include among other things that no one is to taste or even smell the food before the Brahmanas are fed. The householder and his immediate family eat the food only after the Brahmanas finish the meal.

The meal is not be shared with anyone outside the householder’s immediate family. In fact, in many households, it is common to separately cook a meal for the officiating purohit or other visitors who may be present.

The basic premise here is that one must not eat food that has been desired by another being, as one would be guilty of committing an offense. The householder must also not eat food when a person has been sent away from the house empty-handed and in hunger.

A householder that eats while his wife, children or dependents are not fed is also guilty.

Since it was a shraddha day, it is not quite plausible that Ayyaval would have left the house before the ceremony was over. Since even visits to the temple are avoided on the shraddha day, it is possible that some hungry person happened to pass by and asked for food.

Since, the hungry person had desired the food, it would be sinful for the Brahmanas and Ayyaval’s family to eat the food without giving it to him. So, the story goes that Ayyaval shared the food with the hungry person and had a fresh meal prepared for the shraddha.

The question is now of which is preferable – To carry the burden of serving leftovers to the ancestors and gods embodied in the Brahmanas? Or to feed the Brahmanas, who had come for the shraddha and other members of the family, the food which had been desired by a hungry person?

Ayyaval’s act was one of spontaneous compassion, so from a 20th/21st CE viewpoint, one would automatically place less importance to having less than perfect arrangements for a shraddha ceremony. However, placing the story in the context of an 18th CE agraharam, the question did not have an easy answer. This point must have been debated by the scholars of the hamlet. The resolution reached was that the food, even though freshly prepared, was still leftover, and Ayyaval had to take a bath in the Ganga to absolve himself of having tried to serve leftovers at a shraddha ceremony.

Now, with the Ganga appearing in Ayyaval’s backyard well, the issue was resolved firmly in favour of Ayyaval’s compassion.

An interpretation

In the respondent’s own humble view, this story does not indicate that rigour in ritualism is to be dispensed with. The reasons are manifold – Firstly, Sridhara Ayyaval himself did not seek to ignore the importance of the ceremony, as seen from his preparation of a fresh meal for the ceremony. This shows that his sincerity towards ritual was undisputed.

Secondly, Ayyaval was not only a bhagavata (devotee), but also a learned scholar and committed dhaarmika. His compassion, bhakti and shraddha were such that his deviation from practice was sanctioned because of the sincerity and compassion behind it.

This neither indicates that the rituals are to be dispensed with nor do feeding poor as an act of charity can supplant the shraddha ritual. Instead, both have their own place and importance in Dharmic worldview.