।। प्रस्थापित स्वराज्ये शिवाजीना

बाजिरावेण साम्राज्ये परिवर्तितम ।।

The swarajya established by Chhatrapati Shivaji was converted into an empire by Peshwa Bajirao

In the first part of this series, we had seen how the Marathas had first come into contact with Maharaja Chhatrasal Bundela. That was in 1660s. Many years would pass before the Marathas found themselves once again in the thick of politics in the arid Tarai and Bundelkhand region.

This happened with Peshwa Bajirao’s entry into those parts in the closing years of 1720s.This episode is today very famous, I would say almost exclusively famous for a certain Mastani and her affair with the Peshwa, but there is a lot more to the Bundelkhand campaign!

While a few popular books and now one popular movie has been produced on Peshwa’s love affair, the actual conquest of Bundelkhand by Peshwa Bajirao and its importance has somehow been lost. Here is my small attempt to rectify the same.

The strategic importance of Bundelkhand

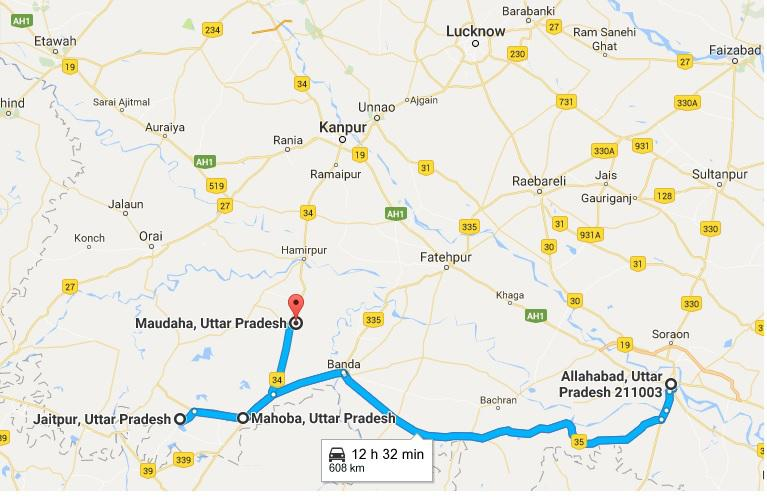

The region of Bundelkhand is located on the border of today’s Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. As the below map will show, it borders the Malwa and Terai on the west and south , the very important Ganga – Jamuna doab on the east and of course the capital Delhi to the north. Control over Bundelkhand meant exercising influence over these regions. Naturally, it was a coveted area.

Chhatrasal Bundela’s swarajya

Maharaja Chhatrasal Bundela was present as a sixteen year old in the Mughal camp during Mirza Raje Jai Singh’s famous invasion of the Deccan. His father had been killed fighting the Mughals. During this campaign (1665), he realised that the person he was fighting – Chhatrapati Shivaji, was opposing the Mughals for a very noble cause! He met Shivaji, who inspired him to rise against the Mughals and free Bundelkhand from the Mughal yoke.

Likewise, he raised a small army around 1671. Taking full advantage of Aurangzeb’s absence from Delhi (1681 to 1707), he freed Bundelkhand. Jhansi, Orchha, Sagar, Panna, and Banda were some of the places which came under his rule. (More details were provided in Part 1)

Mohammed Khan Bangash – Bundelkhand campaign

In 1721, the Mughal emperor had named Mohammed Khan Bangash as the Subhedar of Allahabad. From his capital, he carried out raids at Agra and various places. He was also an important part of politics at Delhi.

Around 1727, wary of Maharaja Chhatrasal’s growing influence, the Mughal ordered Mohammed Khan Bangash to cut him to size. The latter sent his son, Pir Khan – who was killed in a battle with the Bundelas. Then, he sent an able general – Dalel Khan, who was also killed battling the Bundelas. Highly incensed, at the head of a large army, Mohammed Khan Bangash set out in person to defeat Maharaja Chhatrasal Bundela. Starting from Allahabad, he proceeded to various places such as Mahoba, Bhind, Maudaha, Simoni etc., before reaching Jaitpur. Several forts in Bundelkhand region– such as Barigad, Lauri, Jhunar, Kulpahar etc. were captured by him. Finally, he laid siege to the fort at Jaitapur, where Chhatrasal had retreated. Heavy fighting ensued, with Bangash receiving plenty of help from Delhi, courtesy the emperor and Khan Dauran. Also, his son Kaim Khan was at the Red Fort.

By December 1728, Jaitapur passed into the hands of Bangash. Maharaja Chhatrasal surrendered to Mohammed Khan Bangash. The Mughal Subhedar occupied the fort and it seemed a matter of time before his rule was consolidated in the all-important region.

Maharaja Chhatrasal Bundela decided to appeal to the Peshwa for help.

Chhatrasal Bundela’s appeal to the Peshwa

He decided to take help of the Peshwa, who at the time was involved in the Malwa region, winding up operations against Giridhar Bahadur. In fact Chimaji Appa had laid siege to Ujjain at that point of time.

Chhatrasal Bundela invoked the tale of Gajendra and Shri Vishnu when asking Bajirao for help. Just like Shri Vishnu had saved Gajendra from the grasp of a crocodile, so must Bajirao save him from the grasp of Bangash.

The letter goes thus —

” जो गती ग्राह गजेंद्र कि, सो गति भई हैं आज

बाजी जात बुंदेलकि, राखो बाजी लाज”

The interesting part of this stanza is the word ‘Baji’ which has two meanings. In the first instance, it means a pawn in a game of chess; while in the second it directly alludes to Bajirao!! The letter was sent in the hands of one Durgadas.

Now comes the most interesting and inspiring part of this whole incident.

Bajirao began proceeding to Bundelkhand without bothering about the “advantages” of doing so. There was no talk of sharing tributes, granting jagirs etc. There was no mention in that letter of even sharing the cost of transporting a large army from Satara to Bundelkhand. What prompted Peshwa Bajirao to immediately say yes? A knowledge of history? Affinity for a fellow Hindu? Perhaps both. But this selfless act of Bajirao is perhaps the high water mark of this campaign.

The Peshwa, having met the Chhatrapati, started out by way of Bir, Pathri and Deogarh. He then proceeded to Mahoba and Mahur. With him were Pilaji Jadhav, Naro Shankar, Tukoji Pawar and others. His army was around 25,000 strong.

On the 4th of March 1729, was the festival of Holi. Maharaja Chhatrasal Bundela managed to convince Mohammed Khan Bangash to allow the Bundela chieftains to gather for the festival some distance away from Jaitpur. One of his sons also joined them.

The Peshwa’s army swiftly neared Jaitpur. He took the Bundela forts and met Chhatrasal Bundela’s son on the 10th of March.

Defeat of Mohammed Khan Bangash

The Bundelas, seeing the arrival of Bajirao, quickly rallied around his flag and the Maratha army swelled to over 70,000!

Mohammed Khan Bangash was first attacked at Mahoba. The Peshwa’s cavalry ran roughshod over the hapless Mughal Subhedar’s troops.

From the north, Kaim Khan approached with an aim to relieve his father. The Peshwa let him reach Supe, around twelve miles from Jaitpur, where his army was completely surrounded and annihilated. The Mughal emperor, wary of the Peshwa, took the wise decision of staying away.

Mohammed Khan Bangash now retreated to the fort of Jaitpur. Bajirao promptly laid siege to the fort. Typical siege tactics were followed here — that of cutting off all supply routes and starving the garrison inside. Pilaji Jadhav carried out the siege with great vigour.

A letter by him, sent around a month or so into the siege, states that in a week’s time Bangash was either bound to be completely defeated or come to terms.

Finally, in May 1729 Mohammed Khan Bangash retreated from Jaitpur. He agreed never to enter Bundelkhand again.

With monsoons nearing, Peshwa Bajirao also hastened to the south, bringing to an end a short, but glorious campaign.

So what did he gain? Quite a lot more than just Mastani!

Effects of the campaign

- The twin victories over Giridhar Bahadur and Bangash stamped Bajirao’s authority over north India.

- Chhatrasal Bundela gave one third of his kingdom to Bajirao. Thus, Maratha rule started in Jhansi, Sagar, Banda, etc.

- Marathas got a launch pad to push further north and consolidate the Malwa region.

- Marathas became major players in the all-important Ganga Yamuna doab region.

- Chhatrasal Bundela gave Bajirao his daughter – Mastani.

The butterfly effect

” The flutter of a butterfly can create a storm half way around the world.”

Maratha rule over Bundelkhand gave us important personalities such as Govindpant Bundela, Naro Shankar Motiwale and in 1857 – the Nawab of Banda, Ali Bahadur and Jhansi ki Rani – Manikarnika Tambe!

References:

- Marathi Riyasat – G.S Sardesai

- Bajirao and Expansion of Maratha empire – Dr Dighe

- Jaswant Lal Mehta

The article has been consolidated by the author from his previous writings at his blog.

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Aneesh Gokhale is the published author of two books. His second book “Brahmaputra” is about Lachit Barphukan , the Assamese contemporary of Chhatrapati Shivaji. His articles on Maratha and Assamese history have appeared in various online and print media. He has also given public talks on a dozen occassions.