Among the various Mahavidyas arguably the most awe inspiring iconography is that of Goddess Chinnamastā. She appears either 5th or 6th in the list of Mahavidyas depending on the progression followed. Not only in Hindu Tantra but Chinnamastā finds herself ensconced in the pantheon of Tibetan Tantric deities as Vajravairochani. Her stunningly ferocious imagery naturally invokes fear and trepidation, matched only by the effects that her sadhana can cause to a seeker.

In Tibetan Buddhism theogony, she is also referred to as Chinnamunda, who, some scholars believe is a form of Vajravarahi. The term vajra denotes an indestructible purity and is often added as a prefix to the names of different spiritual beings. One of the earliest texts which mention Chinnamastā is the Hindu Chinnamastākalpa and the Tantrasara. The latter is the most authentic sadhana compendium for almost all KaliKula practices and it is among this particular stream of Shaktas where upasana of Chinnamastā has been popular historically. The Buddhist equivalent text is the sadhanamala of 12th century where details of Vajravairochani mantra, tantra and sadhana has been mentioned. Whatever be her exact origins, by the 9th century she was already an established Mahavidya among the Tantrics.

ICONOGRAPHY

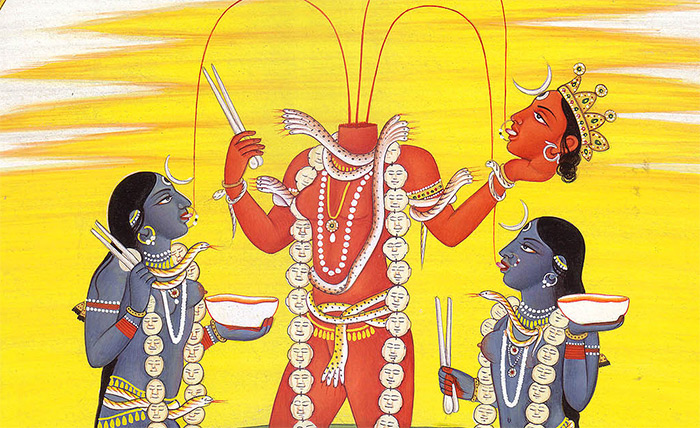

The typical iconography of the Goddess depicts her in deep red color of a hibiscus flower radiating the effulgence of a million suns. Digambari, with a munda-mala (skull garland) and a snake for her yagyapovita, standing in the pratyAlIDha posture, she has cut off her own head and holds it in one of her hands. From her neck erupts three streams of blood which is eagerly consumed by her attendants on two sides, ḍākinī and varini. The third stream goes into her own severed head which she holds in her left hand. Her other hand holds a khadga, and oftentimes she has a blue-lotus in her heart.

We can find the specific dhyana mantra from the Tantrasara.

madhye tu tAm mahAdevIm sUrakoTisamaprabhAm |

Chinnamastām kare vAme dhArayantIm samastakam ||

pibantIm raudhirIm dharma nijakaNThavinirgatAm |

dakShiNe cha kare kartrIm muNDamAlAvibhUShitAm ||

digambarAm mahAbhImAm pratyAlIDhapadasthitAm |

asthimAlAdharAm devIm nAgayaj~nopavItinIm ||

ratikAmopaviShTAm tAm kechiddhyAyanti mantriNaH |

ḍākinīvarNinIyuktAm vAmadakshiNayogataH ||

dakShiNe varNinIm dhyAyet ḍākinīm vAmake tathA |

varNinIm lohitAm saumyAm muktakeshIm digambarAm ||

kapAlakartrikAhastAm vAmadakShiNayogataH |

devIgalocChaladraktadhArApAnAm prakurvatIm ||

ḍākinīm vAmapArshve tu koTisUryAnalopamAm |

daMShTrAkarAlavadanAm pInonnatapayodharAm ||

mahAdevIm mahAghorAm muktakeshIm digambarAm |

lelihAnamahAjihvAm muNDamAlAvibhUShitAm ||

kapAlakartrikAhastAm vAmadakShiNayogataH |

devIgalocchaladraktadhArApAnam prakurvatIm ||

Various scholars have tried to decode and read different meanings into this awe-inspiring imagery including some like the very learned Shankaranarayan, who finds Vedic imports in the origin and symbolism of Chinnamastā. He writes:

“[she] is the thunder clap and the lightning flash. ‘Shinning like a streak of lightning’ (vidyullekheva bhAsvarA). That is why Chinnamastā is known as vajravairocaniya. She is the force of Virochana, the specially luminous (visesena rocate’iti virochanah). Who is this Virochana? The Supreme itself, the primodial prakasha. Vajra is her power which he wields. We know Vajra is the weapon of Indra… in the Veda, the paramount deity.”

However, the imagery lends itself to a less strenuous and more comprehensive explanation using standard Tantric concepts. The three bloodstreams symbolized the three fundamental ethereal nerves inside the subtle body – ida, pingla and susumna. Blood is generally considered to be the best representative of prana inside a human being, hence the vamachari preference for blood-drinking goddesses – symbolizing raktashuddi – and the more practical manifestation of blood sacrifices. Without going all superficial and Maneka Gandhi on things, we should at least try and understand why KaliKula tantra sadhakas use sacrifices and how they can form, in some cases, an indispensable part of the ritual. Not only that, blood or rakta is also an indispensable part of certain rituals. The heart of Tantric sadhana and prayogaas lies in use of exact ingredients at the right time for the perfect ritual. Nothing is arbitrary or whimsically done. Prana, which keeps us alive and ties the mind to the body, while we live, can be used along with the apana-vayu to awaken inside the human mind-body complex that overused, misrepresented and yet inexplicably powerful of occult forces inside the human adhara, Kundalini. While ida and pingla are important for balancing and controlling our daily psychology, Kundalini passing through the susumna comes into play when a first contact with an other worldly spiritual atmosphere is made such that our sense of reality starts changing, hopefully for the better. But what about the severed head? The journey of the Kundalini is meant to continue until it reaches the top of the head and merges into the sahasrara. Which is another way of saying that the Kundalini can go up to the final destination only when the constant churning of the normal mind is forced to stop. No body whose mind runs around like a monkey on a roller coaster can ever seriously hope of experiencing the full awakening of the Kundalini Shakti. Thus, Chinnamastā is the form of Adya Kali who cuts off the rationalizing mind in one shot and pushes the tremendous force of Kundalini right onto the top of the skull like a reverse bolt of lightning! Given the abruptness and exceptional danger involved in this process, very, very few people really have the nerves needed to experience or perform a successful sadhana of this form. No wonder the Tantrasara calls her Prachanda Chandika (Chandi herself being fierce, Prachanda Chandika is super fierce) as well as Sarvasiddhi – who grants all siddhis. The Sadhanamala describes her as sarvabuddhi – complete intelligence, or enlightened intelligence. This author has seen even tantric adepts with decades of experience overcome by fear when attempting to perform Chinnamastā upasana. Naturally, such sadhana requires an appropriate setting which adheres to the recommendations of Tantra sadhana and a competent guru who can judge if a sadhaka is capable of this practice. Another vital element in the iconography is the fact that Chinnamastā stands on two copulating body. Celibacy is of great importance, at least during the initial phases, for the practice to succeed and cause no harm to the practitioner.

ANTIQUITY

Chinnamastā is also known as Vajra Vairochani. Vairochana is related to sun or fire, of a solar disposition. Vajra is not just a thunderbolt but also something adamantine or impenetrable. Vajravairochani is the force of an adamantine, inexhaustible fire. This etymology has led many sadhaka-scholars to speculate that this Mahavidya is best experienced when the Kundalini – which is often equated with subtle fire – awakens with a deadly force from the manipura chakra at the solar plexus of the body. The most commonly used mantra of Chinnamastā refers to the goddess as vajravairochani.

However another simpler explanation for the suffix vajra is the link that the deity bears to the Vajrayana tradition of Tibet. It has left scholars speculating whether Chinnamastā was originally a Hindu deity or a Buddhist goddess, imported into Hinduism. The texts which contain the dhyana references to the goddess are later compositions and as such not of much help with dating. In the Buddhist compendium sadhanamala, we find Vajrayoginī, an anuttarayoga iṣṭadevatā, bears a surprising iconographic similarity with Chinnamastā. Vajrayogini is considered to be a deity with supreme control over the intermediate states between death and rebirth and have over centuries gathered a standalone cult of practitioners who approach her both for mundane and the supernal realizations. The most common epithet used to describe Vajrayogini and one that is used in the mantras given in sadhanamala is sarvabuddhaḍākinī – a ḍākinī who is the essence of all Buddhas, while her companions as per this compendium are vajravarnini and vajravairochani. Scholars are of the opinion that the sadhanamala, which contains about 300 different practices, was composed somewhere around the 5th century AD, and therefore it would not be unreasonable to assume that Chinnamastā or Vajrayogini had already developed into a mature practice by the time this text was written down.

APPLICATION

A crucial part of any Tantric sadhana is application or prayogaa, which is different from mukti. Philosophically there is no conflict in keeping a greater focus on application, or using the power of a deity only for the limited purpose of a specific prayogaa, instead of performing the sadhana for a great spiritual benefit. Chinnamastā sadhanas, given the extremely ferocious nature of the deity, are most often used to bring about destruction of ones enemies. Sadhaks have recorded the effects that this deity has on the mind, creating, in some cases, a great sense of fear, and then teaching the practitioner to overcome that fear. The sadhana also involves sexual continence, for she stands on Kamdeva and Rati, and the power generated through the control of sexual energy is then used to push the Kundalini Shakti into the central channel of the subtle body known as the susumna. However, in the Buddhist tradition worship of Yabyum deities, of which vajrayogini can be an element, does require a suitable partner if the 5th makara is to be performed. Unknown to casual readers, the original mantra sadhana of Chinnamastā involved an invocation not only to Chinnamastā but also to her companions ḍākinī and varini. Here too we find the sadhanamala using triple beejas, probably to represent each of the three deities in the full pantheon. This format of course underwent many changes with the Tantrasara, among other texts, prescribing many variation of the beejas used in the Chinnamastā mula mantra. Apart from texts of course there is also a vast living tradition and wealth of information on the goddess, and the effects of the sadhana as passed down in various Kaula paramparas. For example when Chinnamatsa homas are performed using Combretum indicum, one may attain the vaksiddhi; while using Plumeria flowers may grant a suitable sadhaka great sukha. Similarly white Thevetia peruviana used in Chinnamastā fire ritual frees one from all kinds of diseases, the red version of the same flower generates ākarṣaṇa shakti in the sadhaka. Some even use dhatura – species of poisonous vespertine flowering plants- for some of the more dangerous prayogas using Chinnamastā mantras.

A less ambitious application of Chinnamastā sadhana is for nullifying the effects of Rahu as a graha. Probably the most important center of Chinnamastā worship in India exists in Rajarappa in the state of Jharkhand. Located at the confluence of the Bhairavi nadi and the Damodar nad (male river), it has been a place of great reverence for people of the state as well as devotees from Bihar, and West Bengal. After a theft and desecration in the temple in 2010, artisans from Rajasthan were called to remake the idol carved out of dark Hessonite – gomedh – which is the recommended stone for Rahu, and thereafter a 9 day pranapratistha ritual and Chinnamastā homa was conducted.

But Kamya prayogas are not the only way to approach this deity. They may be popular no doubt, but history is not without great sadhaks who have approached her for communion and spiritual uplift. An oft repeated caveat must be in place. All such practices need the guidance of a Guru who knows the path. These are too dangerous for casual experimentation and may complicate matters in the hands of novices. Raja Krshnachandra of Bengal, a contemporary of shakta-poet Ramprasad Sen, was reputed to be a sadhaka of Chinnamastā. The Tantric author Taranath mentions that Kanipa or Krshacharya, one of the 84 Mahasiddhas of Tibetan Buddhism, had two female disciples from the area of Maharashtra, Mekhala and Kanakhala, who were experts in Chinnamastā sadhana having attained communion with the goddess. These two female adepts were also considered as Mahasiddhas in the tradition. In the Hindu Mahavidya tradition, Chinnamastā is accompanied by Krodha Bhairava, and among the twenty-four avatars of Vishnu mentioned in the Bhagwatam, Chinnamastā is equivalent to the Narasimha avatāra.

Finally, however the most beautiful aspect – for awe and beauty can go hand in hand – of her unique imagery is the fact that it is her own decapitated head that drinks the blood gushing out of her neck. No better symbolism could have captured the Vedantic truth of the all-pervading Brahman who is both everything and nothing – Herself the sacrifice, Herself the sacrificer, Herself the sacrificed.

Feature Image: http://www.indiadivine.org

Svechchachari is the pen name of a tantrik sadhaka, who wishes to remain anonymous so that he is able to express his opinions and share his experiences more freely through his writings.