Bhagavad Gita – The Name of the Scripture

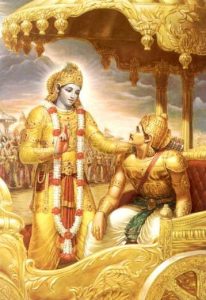

The title of this beloved Hindu scripture literally means “The Divine Song” or the “The Song of the Lord”. This holy book of Hindus presents an eternally relevant dialogue between a human representative (Arjuna) and the Supreme Being (as Krishna). The Bhagavad Gita is often referred to simply as the ‘Gita’ in short. Many other Gitas exist in the Hindu scriptural tradition, but when the word ‘Gita’ is used, it denotes our Bhagavad Gita, because of its pre-eminence over all the other Hindu Gita scriptures.

The title of this beloved Hindu scripture literally means “The Divine Song” or the “The Song of the Lord”. This holy book of Hindus presents an eternally relevant dialogue between a human representative (Arjuna) and the Supreme Being (as Krishna). The Bhagavad Gita is often referred to simply as the ‘Gita’ in short. Many other Gitas exist in the Hindu scriptural tradition, but when the word ‘Gita’ is used, it denotes our Bhagavad Gita, because of its pre-eminence over all the other Hindu Gita scriptures.

Importance of the Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita has been considered one of the most important scriptures of Hindus for over 2000 years. The name of this Hindu scripture means the Divine Song, or Song of the Lord, or Sung by God because it is a dialog between God (in the form of Lord Krishna) and human beings (represented by Arjuna). The scripture is referred to as ‘Gita’ in short. The scripture is almost universally regarded by Hindus as the epitome of all the spiritual teachings of the Vedas and the Upanishads and is read by millions of Hindus for inspiration and solace to this day. Many Hindus memorize all of its 700 verses, or at least selected chapters and verses to draw upon their teachings and to teach others. Hindu tradition says that the verses of Krishna are recorded exactly as they were uttered by Him. Arjuna’s speech was in prose, and it was versified later by Rishi Veda Vyāsa.

How ancient is the Bhagavad Gita?

The Gita is said to have been revealed to humanity around 3100 BCE. Some historians date it to 1400 BCE, whereas others think of 500 BCE. Many other scholars give it a date of around 100BCE to 100 AD in its present form. The tree under which Krishna revealed the Gita to Arjuna still exists in Kurukshetra in Northern India, and is an object of worship.

Gita and Other Scriptures

The Bhagavad Gita is a part of the much larger scripture – the Mahabharata. It forms chapters 23-40 in the Bhishma Parvan – the 6th of the 18 books of the Mahabharata. The Gita has 700 verses in the standard version (taken to be the version on which Adi Shankaracharya wrote his commentary) but there are traditions to the effect that the scripture had 745 verses. Some manuscripts from Kashmir and NW India have 14 or so additional verses, and some commentators have also noted some extra verses. But none of these additional verses add anything significant to the teaching of the Gita. In the standard version of 700 verses, 574 are spoken by Lord Krishna, 84 by Arjuna, 41 by Sanjaya and 1 by King Dhritrashtra. The Gita has 18 chapters which have different titles. However, different commentators and different manuscripts either sometimes omit these titles or give different titles for the same chapter. This is taken to mean that the addition of titles to these chapters took place at a later time, and that the chapters did not have names originally. Moreover, these titles often do not necessarily reflect the actual contents of these chapters faithfully.

The Gita has been so highly esteemed since ancient times that dozens of slightly different adaptations were composed in imitation of the original and incorporated into different scriptures. For example, the Ganesha Gita occurs in the Ganesha Purana, the Ishwara Gita in the Kurma Purana, the Devi Gita in the Markandeya Purana and the Brahma Gita in the Suta Samhita of the Skanda Purana. Within the Mahabharata itself is included the AnuGita, in which Shri Krishna summarizes and restates some portions of the Bhagavad Gita to Arjuna upon the latter’s request. In addition, the Bhāgavata Purana (11th book) has a Gita called the ‘Uddhava Gita’, which was narrated by Lord Krishna as his last sermon to His son Uddhava. A fourth Gita of Shri Krishna titled the Uttaragita also exists and it has a commentary attributed to Gaudapacharya, the teacher’s teacher of Adi Shankaracharya. But it is the Bhagavad Gita that is the most popular Gita, and it is even claimed that studying it makes the study of other scriptures unnecessary.

Translations and Commentaries

The Gita is the second most translated scripture in the world, after the Bible. The oldest surviving translation of the Gita is in Javanese, an Indonesian language. This translation covers less than 100 verses and is more than 1000 years old. Literally dozens of Hindu scholars and saints wrote their own commentaries and explanations on the Bhagavad Gita in the last 1500 years or more. The oldest commentary that survives is that of Adi Shankaracharya (~700 AD) and tries to show that the scripture teaches Advaita Vedanta. However, it is clear from this commentary that there existed several ancient commentaries on the Gita but none of these has survived today. He is closely followed in time by Bhatta Bhaskara who interprets the Gita according to the school of Bhedabheda Vedanta. Other prominent Sanskrit commentaries on the Gita are by Ramanujacharya (following Vishishtadvaita Vedanta), Madhvacharya (following Dvaita Vedanta), Vedanta Deshika (super-commentary on Ramanujacharya’s commentary), Shridhara Swami (following Advaita Vedanta with a strong flavor of Bhakti) and Madhusudana Saraswati (Advaita Vedanta with a strong flavor of Bhakti). Around the beginning of the 13th cent. AD, Sant Jnaneshvara of Maharashtra wrote a beautiful verse commentary on the Gita in an olden form of the Marathi language. In our own times, Mahatma Gandhi wrote an explanation on the Gita. Literally hundreds of translations and beautiful commentaries on the Gita in English, Hindi and many other languages have appeared since 1750 AD. Because of its importance in Hinduism, every important Hindu thinker and philosopher feels the need to write a commentary on this scripture from his or her own perspective.

The Teachings of Bhagavad Gita

Hindu Dharma prescribes four legitimate goals of our human existence Artha (material wealth, security); Kāma (fulfilling desires that make our senses and mind happy, sensual and aesthetic pleasures; success); Dharma (virtue, doing one’s duty, piety) and Moksha (liberation from the continuous cycle of births and deaths through spiritual enlightenment). In this tetrad, Dharma plays a pivotal role because it is one must pursue Artha and Kāma if they violate the requirements of Dharma, and also because Dharma provides the edifice on which the edifice of spiritual enlightenment leading to Moksha is constructed.

There are two ways in which Dharma can be practiced. The first is that in which leading virtuous lives prevents us from Adharma (or evil), helps us accumulate good Karma and ensures that we are born into higher and more privileged life-forms during our successive rebirths. This way is called Pravritti Dharma’ – or Dharma that leads us back to the cycle of births and deaths (even though we may advance successively in the hierarchy of living creatures).The second way of practicing Dharma is one in which the person’s focus is to escape the cycle of births and deaths altogether, and not merely advancing in the hierarchy of living creatures in successive births. This is called ‘Nivritti Dharma’, or Dharma that takes us out of this cycle of births and deaths completely. In other words, Nivritti Dharma is practicing Dharma in a manner that assists us in attaining Moksha.

The Gita is primarily a Moksha-Shastra, or a scripture which teaches us how we can practice Dharma so as to overcome the continuous cycle of births and deaths and become one with Brahman, the Supreme Being. The Gita teaches us how to live our lives ethically and spiritually. It describes the different paths to spiritual enlightenment, the correct attitude and world-view that we should have at all times while engrossed in our day to day tasks, and the nature of the final goal – the state of Moksha.

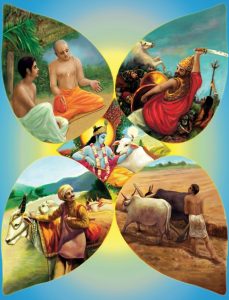

The four main paths to Moksha taught by the Gita are Jnana Yoga, Karma Yoga, Bhakti Yoga and Dhyana Yoga. These paths are not mutually exclusive and we should combine elements from all, even while focusing on 1 or 2 of them. The Gita recognizes the fact that different people have different abilities and temperaments and therefore they may prefer focusing on 1 of the 4 approaches.

The four main paths to Moksha taught by the Gita are Jnana Yoga, Karma Yoga, Bhakti Yoga and Dhyana Yoga. These paths are not mutually exclusive and we should combine elements from all, even while focusing on 1 or 2 of them. The Gita recognizes the fact that different people have different abilities and temperaments and therefore they may prefer focusing on 1 of the 4 approaches.

The path of Jnana Yoga teaches that our soul is the real ‘us’ and it is different from the body. Therefore, we should not get things that pertain to the body, which dies and perishes when we die. The soul survives our death and moves from 1 body to another till we achieve Moksha. When we understand our nature as the spiritual soul and not as the body, we will start focusing more on the really important and spiritual things, and will desist from focusing our efforts and attention towards the things of this physical world. This knowledge and understanding leads us to Moksha.

The path of Karma Yoga states that all the sensations of our sense organs – such as pain, happiness, sorrow, heat, cold etc., are temporary. Nothing lasts forever. Therefore, we should bear them with patience, and not get infatuated with negative emotions, nor should we get attracted by worldly temptations. Instead, we should continue to do our duty at all times just because it ought to be done, and without any desire of fruits resulting from doing them.

The path of Bhakti Yoga is said to be the easiest path, accessible to all irrespective of our educational background, social status or gender. It implies loving devotion to God through worship, and doing all our duties with faith in Him and with a sense of surrender to His will.

The path of Dhyana Yoga teaches that we should not focus all our attention on the external world, because the Supreme Truth and Reality, which is our soul and God, are right within us. Therefore, we should meditate on God, and should not waste our time in pursuing things that hamper meditation, such as strong emotions, strong likes and dislikes etc.

It can be seen very easily that people with different temperaments will focus on 1 or the other paths above. For example, emotional people would prefer the path of Bhakti, introverts and self-reflective people will prefer Dhyana Yoga, intellectuals will prefer Jnana Yoga and action oriented people will prefer Karma Yoga. However, there is no one who does not have some portion of intellectualism, emotion, self-reflection and action aspects in his behavior.

The Bhagavad Gita therefore describes these four paths but also teaches them in a way that spiritual aspirants will follow elements of all these paths even when focusing on one of them. For example, a Karma Yogin will benefit from practicing Dhyana Yoga because it will help him bring his senses under the discipline of his pure mind. He will understand the temporary nature of the physical sensations better if he understands the path of Jnana Yoga to learn about the true nature of our body, our soul, God and this universe. And devoting the fruits of his Karma to God will help him give up the desire for these fruits. Similarly, the follower of Jnana Yoga will give a practical bent to his understanding of the nature of the soul and the body if he actually experiences through Dhyana Yoga. He will not lapse into evil ways if he continues to do his duty towards others (Karma Yoga). And finally, he will not get enamored of dry intellectualism alone if he combines his philosophical and theological insights with devotion and faith in God.

The Gita strongly emphasizes the need to follow the path of Dharma as taught in our scriptures, and continue doing all our required duties throughout our lives. Towards the end of the Gita, Lord Krishna assures us that as long as we continue to do our duties without desire for fruits, as an offering for Him and remembering Him, He will save us from all evil and also grant us Moksha.

Here and there, the Gita has beautiful gems that have become a part of general Hindu repertoire and are recalled by us with great faith, piety and devotion. For example, in Chapter 4, Lord Krishna states how God incarnates on earth to protect Dharma whenever it is in danger of being overwhelmed by Adharma. In Chapter II, he says that just as the body passes through the phases of childhood, youth and old age followed by death, the soul passes from one body to another in its different lives. The soul is never born, it never dies, it is unchangeable and eternal. It cannot be cleaved by weapons, wetted by water and so on. Lord Krishna also teaches us to practice moderation, or seek a balance in our lives while performing our Karma or duties. We should all aspire to become knowledgeable and wise because true knowledge and understanding alone cuts ignorance like a sword. While describing the beautiful doctrine of Bhakti in chapter 8, He says that he accepts the offerings of whosoever offers even water or a leaf to God as long as it is done with faith and devotion. In chapter 16, the Gita condemns superficiality of behavior and asks us to be pure within ourselves, and to combine simple living with high thinking, with faith in God and with a virtuous character. In chapter 18, Lord Krishna recognizes the fact that every action, even if good and done with pure intentions, can lead to a negative result just as fire and light are surrounded by smoke. But this must not deter us from performing our duties required of us. We must, at all times, perform our duties because all activities have a role to play in maintaining stability of our society and the universe.

Contemporary Relevance of the Gita

Question: The Bhagavad Gita is merely a historical document recording the supposed dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna. Then why should we study it today? What is the proof that the dialogue was intended as an eternal and a universal scripture that should be studied in our times by us?

Answer: The Bhagavad Gita is not merely a ‘historical’ document that should be read only to study history, or to appreciate only its literary worth without paying attention to its actual ethical and spiritual teachings. There are several reasons to regard the Gita as an eternally relevant scripture that provides us with guidance on Moksha and Dharma.

Even a cursory perusal of the contents of Gita reveals that it seeks to answer the eternal questions of life, even though it is placed within a specific situational context of the Mahabharata. This simple consideration should be sufficient to show that the characterization of the Gita merely as a historical or a literary document reflect a pedantic and an intellectually dishonest and shallow viewpoint.[1]

Second, the Bhagavad Gita itself points to its eternal relevance. The scripture is indeed intended to provide guidance on questions of life for all times to come. For example, when Sanjaya completes his narration of the Gita with the following words: “Wherever there…..” Even the opening words – ‘dharmakshetre kurukshetre…’ hint that the dialogue that follows them deals with perennial issues of conflict between evil and virtue, between darkness and spiritual enlightenment.

The Mahabharata, of which the Gita is an integral part, is not merely a war epic. Embedded within it are dozens of sections of a didactic nature. A careful consideration of the structure of the epic will reveal that it intentionally embeds these didactic sections within other mundane interesting narratives so that the reader does not get bored with just long sermons one after the other. Embedding parables, sermons, proverbs and spiritual treatises within the overall context of the story of the Mahabharata also enables the reader to see the practical implications and applications of these edifying teachings. The same can be said of the Gita as well. The Gita is placed within a particularly challenging situation within the Mahabharata where Arjuna, one of its main characters, is faced with numerous moral dilemmas that cripple and drain him physically and mentally. Very often, we find ourselves in similar situations, and incorrect decisions taken at these junctures can lead us to complete ruin. In response, Lord Krishna then provides Arjuna with spiritual solutions that can fit almost any context in our own lives.

Later Hindu scriptures also state the importance of the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita. For example, the Padma Mahāpurāṇa …Numerous adaptations and imitations of the Gita are found in several other Hindu scriptures. E.g., the Ishvara Gita in the Kūrma Purāņa, the Ganesh Gita in the Ganesh Purāņa and so on. This too suggests the immense and continued popularity of the Gita as a scripture that teaches eternally relevant doctrines and principles.

If the Gita were merely a historical record with no eternal relevance, dozens of great Hindu philosophers and scholars would not have labored in writing commentaries on it over the last several centuries. Obviously, they saw the importance of its teachings and their relevance and therefore tried to explain it to lay Hindus by writing their massive scholarly commentaries and glosses on this scripture.

Many noteworthy Hindus as well as non-Hindus have found solutions to their problems through the Gita. For example, Mahatma Gandhi once wrote – “I have had no less share of great tragedies in my life. But whenever I am in trouble, I rush to Mother Gita as a child, and find a verse or a phrase here or there, that provides an answer to my problem, and gives me great comfort (paraphrased).”

There are very few verses in the Gita that are specific to the exact historical context of the Mahabharata war, which seems to be a literary muse to expound eternal Hindu teachings. The scripture predominantly deals with eternal questions that plague our minds and conscience, and provides numerous complementary and supplementary solutions in keeping with the complexity and diversity of our individual lives.

In conclusion, restricting our appreciation of the Gita to its historical and literary aspects alone can be misleading and deprives us of its true worth. The Gita provides answers to our moral dilemmas and gives hope to the hopeless, to the helpless and the needy by exhorting us to be strong, have faith in God, and have a deep commitment to performance of our duties. We must never give up and continue to take small steps towards our goals, while never forgetting God.

The Bhagavad Gita – A Summary

Arjuna said to Lord Krishna:

Overcome by faint-heartedness (a sinking feeling), confused about my duty (Dharma), I ask you: Please tell me that which is truly better for me. I am your student. Please teach me, who has taken refuge in you. Gita 2.7

The Blessed Lord Krishna replied:

[GOD IS THE SUPREME BEING]

I am the final Destination (Goal), the Provider, the Master of all, the Witness of everything, the Abode (in which the whole universe resides), worth seeking shelter of, and the Friend of all. And I am the origin and the Dissolution, the Foundation of everything, the Resting Place and the immortal cause of everything. Gita 9.18

An eternal portion of My own Self becomes the soul of creatures in the world of living things. It attracts the five senses and the mind as the sixth (which lords over these senses) – all these six are comprised of non-living matter. Gita 15.7

[SEE THE DIVINE IN ALL CREATURES]

The wise see the same (Brahman) with an equal eye, in a learned and humble brāhmaṇa, in a cow, in an elephant, in a dog, and even in a dog eater (outcast). Gita 5.18

[WE ARE THE ETERNAL SOUL, NOT THIS PERISHABLE BODY]

The soul is never born and it does not ever die. The soul is not something that exists at one time and then vanishes the next. The soul is not something that did not exist at one time and then took birth and came into being subsequently. It is unchanging, eternal and primeval and it is not destroyed when the body is destroyed. Gita 2.20

Weapons cannot cleave the soul, fire cannot burn it. Water does not wet (or drown) it not does wind dry it. Gita 2.23

[DOCTRINE OF REBIRTH – WE NEVER DIE]

Just as a human casts off worn out clothing and puts on new, the soul too casts off old bodies and enters into new ones. Gita 2.22

Just as the soul dwelling in the body passes through childhood, youth and old age; in a similar manner, it travels from one body to another. Therefore, the wise do not get deluded over these changes. Gita 2.13

When the soul enters a body, it becomes the master of that body. And when it leaves the body (at death), it takes the mind and senses along with it, just as the wind takes fragrances from their sources (the flowers). Gita 15.8

[GOD IS IMPARTIAL]

All beings are equal in my eyes. There is none especially hateful to me, nor one who is especially dear to me. But all those who worship me with devotion are in Me, and so am I in them. Gita 9.29

[THERE IS HOPE FOR EVERYONE]

Even if a person of the vilest conduct starts worshipping me with single-minded devotion, he too must be counted amongst the good, because he has resolved well. Gita 9.30

[GOD SAVES ANYONE WHO APPROACHES HIM]

Whosoever takes refuge in me, even if they are lowly born (due to the sins of their previous lives), and be they women, or Vaishyas or Shudras – they will all attain the Highest Goal. Gita 9.32

[TRUE DEVOTION IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN EXTERNALS]

Whosoever offers to Me with devotion a leaf, a flower, a fruit or even water – that offering of love, of the pure of heart I accept eagerly. Gita 9.26

[MANY WAYS TO REACH GOD – FREEDOM OF WORSHIP]

In whatsoever way men approach Me, even so do I bless them. For whichever path that men make take in worship, they will all come to Me. Gita 4.11

He who has no hatred for any living being, who is friendly and also compassionate instead, who is free of the feeling of ‘I’ and ‘mine’, even minded in pleasure and pain and ever forgiving and forbearing. Gita 12.13

He who is alike to enemy and friend, also to good or bad reputation; He who is the same in pleasure or pain, in heat or cold and who is free from all attachments. Gita 12.18

He who considers insult and praise alike, who is silent (restrained in speech), content with whatever comes his way (through his own effort), has no abode (i.e., is not tied to home or family) and is firm in mind and full of devotion – that man is extremely dear to me. Gita 12.19

[LIVING ETHICALLY AND SPIRITUALLY]

Absence of fear, purity of mind, steadfastness in the path of meditation, Charity, control over one’s sense organs, performance of Vedic sacrifices, study of Holy Scriptures, austerity and straightforwardness… Gita 16.1

Ahimsa, truthfulness, absence of anger, renunciation, peacefulness, absence of backbiting or crookedness, compassion towards all creatures, absence of covetousness, gentleness, modesty (decency), absence of fickleness (or immaturity)…. Gita 16.2

Vigor and energy, forgiveness, fortitude, cleanliness, absence of hatred and no exaggerated self-opinion – These belong to the One who is born to achieve Divine Wealth, O Bhārata. Gita 16.3

Ostentation, arrogance, excessive pride and a tendency to demand respect, anger, harshness and indeed ignorance – these are the endowments of him who is born with the demoniac wealth. Gita 16.4

[LAW OF KARMA, FREEDOM IS OUR TRUE DESTINY]

[LAW OF KARMA, FREEDOM IS OUR TRUE DESTINY]

Divine wealth leads to Freedom, whereas the demoniac wealth results in bondage. Do not grieve, because you are born naturally with the divine wealth (and therefore destined for freedom). Gita 16.5

[CONTROL YOUR WANTS TO ATTAIN PEACE AND HAPPINESS]

He attains peace into whom all desires enter as waters enters the ocean, which filled from all sides, remains unmoved; but not to him who wants to have (more and more) desires. Gita 2.70

[PRACTICE MODERATION IN ALL THINGS]

Meditation (Yoga) becomes the destroyer of sorrow for him whose food (eating habits) and recreation are temperate, whose efforts and activities are controlled, and whose sleep and waking are regulated. Gita 6.17

[ENGAGE WITH GOOD, DISENGAGE FROM EVIL]

Arjuna, without doubt, the mind is difficult to discipline because it is restless. But it can be restrained through constant engagement in good things (abhyāsa) and constant detachment from bad things (vairāgya). Gita 6.35

[SCRIPTURAL TEACHINGS SHOULD BE OUR GUIDE IN OUR ACTIONS]

Let scripture be the means by which you determine what should be done and what should not be done. After knowing the commands of the scripture, it is your obligation to perform your duties while you live in this world. Gita 16.24

[GOD SETS AN EXAMPLE THROUGH DIVINE INCARNATIONS]

Whenever there is a decline of Dharma and ascendancy of Adharma, I bring Myself into being, i.e., I assume a physical body. Gita 4.7

To protect the virtuous, destroy the evil doers and to re-establish the rule of Dharma, I come into being in every age. Gita 4.8

[WE TOO SHOULD SET AN EXAMPLE FOR OTHERS]

Whatsoever a great man does, the same is done by others. Whatever standard he sets, the world follows. Gita 3.21

[DO YOUR DUTY WITH A HIGHER PURPOSE]

The unlearned performs their duties from attachment to their work. Therefore, the wise and learned too should perform their duties, but without any attachment and only with the desire to promote harmony and welfare in the world. Gita 3.25

[BE STRONG, BELIEVE IN SELF-HELP]

Let a man lift himself by himself; because we alone are our own friend and we are also our own enemy. Gita 6.5

[DO YOUR DUTY SELFLESSLY, WITHOUT EXPECTING REWARDS]

[DO YOUR DUTY SELFLESSLY, WITHOUT EXPECTING REWARDS]

You have control over doing your duty alone, and never on the fruit of your actions. Therefore, do not live or do your duty that is merely motivated by fruits of your actions. And do not let yourself get drawn into the path of non-action. Gita 2.47

[TAKE PRIDE IN WHATEVER YOU DO]

One should not give up the work suited to one’s nature, though it may be defective, for all enterprises are clouded by defects, just as fire is covered with smoke. Gita 18.48

[ALL WORK IS IMPORTANT]

One’s duty, even if devoid of merit, is better than the duty of another, well done. Doing action ordained by one’s own nature, one does not incur any sin. Gita 18.47

[CORRECT MENTAL ATTITUDE IN DOING OUR DUTY]

Steadfast in Yoga, and abandoning attachments, perform your actions and duties. Face all accomplishments and failures with an even mind, because yoga means evenness of mind. Gita 2.48

[WHEN WORK BECOMES WORSHIP]

(For a person who is immersed in spirituality) The act of offering is Brahman. The offering itself is Brahman. By Brahman is it offered into the fire, which is Brahman too. He who realizes Brahman while performing all actions, indeed reaches Brahman. Gita 4.24

[WE ARE INSTRUMENTS OF GOD]

The Lord resides in the hearts of all beings, causing them to revolve (i.e., go about their tasks) through his Māyā as if they were mounted on a machine. Gita 18.61

[GOD’S PROMISE TO US]

Abandoning completely all duties (i.e., dedicating them to Me), seek refuge in Me alone. I will liberate you from all evil, therefore do not grieve. Gita 18.66

[SPREAD THE GOOD WORD]

He who teaches this most exalted and supreme secret – this scripture (Gita) to My devotees, while having the highest devotion to Me, will come to Me alone – let there be no doubt about this. Gita 18.68

Arjuna said:

O Lord! You are Imperishable, the Supreme Being that we should seek to know. You are the ultimate shelter of the entire universe. You are the relentless protector of eternal Dharma. I believe that You are that Being Who has existed since eternity. Gita 11.18

By Your grace, my delusion is gone; and I have gained recognition of who I am and what is my duty. I now stand firm with my doubts dispelled and will do as You say. Gita 18.73

[1] In our times, this viewpoint is seen in the writings of India’s Marxist historians such as D D Kosambi, D N Jha, R S Sharma, Romila Thapar etc.

Featured Image: Fine Art America

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Vishal Agarwal is an independent scholar residing in Minneapolis (USA) with his wife, two children and a dog. He has authored one book and over fifteen book chapters and papers, some in peer reviewed journals, about ancient India and Hinduism. He and his wife founded the largest weekend school teaching Hinduism to students, and also a teenager organization to keep them engaged in Dharma. Vishal has participated in numerous interfaith forums, and has represented Hindus and Indians in school classrooms and in seminars. Vishal is the recipient of the Hindu American Foundation’s Dharma Seva Award (2010), the Global Hindu Academy’s Scholar award (2014) and service awards from the Hindu Society of Minnesota (2014 and 2015). He is very strongly engaged in the social and Dharmic activities of the Indian and Hindu communities of Minnesota, and has authored a series of ten textbooks for use in weekend Hindu schools by children from the ages 4-14. Professionally, Vishal is a biomedical Engineer with graduate degrees in Materials Engineering and Business Administration (MBA). His scientific and statistical training enables him to bring precision and a high level of rigor in his research – qualities that are very often missing in contemporary publications on Indology and in South Asian Studies.