Traditionally, neither the Indian nor the Chinese civilisations were particularly well-known for practicing slavery. During the ancient and classical periods, neither India nor China ever practiced chattel slavery, wherein slaves were traded like commodities in a market. Chattel slavery was common in many other contemporary societies. One possible reason could have been that the relatively large populations in India and China provided enough non-slave human labour. Thus, the impetus to enslave people on a massive scale was perhaps not there. In contrast, the economies of many other societies in Europe, Africa, the Americas and West Asia, some even until modern times, prominently depended upon slavery.

During the Islamic rule in India, real slavery took hold in a different way as the Islamic rulers began enslaving the Indian population to sell them abroad for profit or to utilise their slave labour within the country.

Dasas in ancient and classical India

Although chattel slavery was not seen, some forms of bondage did exist in ancient and classical India. At the outset, it is important to highlight the fact that the word dasa used in many Indian texts does not necessarily refer to slave. It usually refers to a servant. It appears that the circumstances of the dasa was far better in ancient Indian society in contrast to the excessive brutality experienced by the slaves of contemporary societies such as Egypt, Greece or Rome. While examining the ancient past of India, one comes across the comparatively constrained existence of any form of bondage.

The Buddha (c. 560 – c. 480 B.C.E.) cautioned his ordinary adherents to not overwork their servants and to be compassionate should any illness befall them.

In his Arthashastra, Kautilya (c. 2nd – 3rd century B.C.E.) dedicated a chapter prescribing rules about how dasas should be treated. The master was not to punish a dasa without reason and those who mistreated their dasas were liable for prosecution. Also, the selling of kinsmen as dasas was forbidden for Aryas but was permitted for Mlecchas. This indicates the divergence between the Arya culture of India and the foreign Mleccha culture as was evident even 2200 years ago during the time of Kautilya.

Kautilya further indicates that the selling of another person against his will is punishable up to being subject to capital punishment. Contrast this with the selling of millions of innocent Africans which facilitated the 17th and 18th century Atlantic slave trade between the Americas, Europe and Africa. The Arthashastra however does permit a person to voluntarily submit himself to bondage to pay off any debts. Also, the acts of deceiving a dasa of his money or depriving him of his privileges as an Arya made one liable for punishment. Any mistreatment of dasas also was heavily punishable. This indicates that dasas were treated humanely.

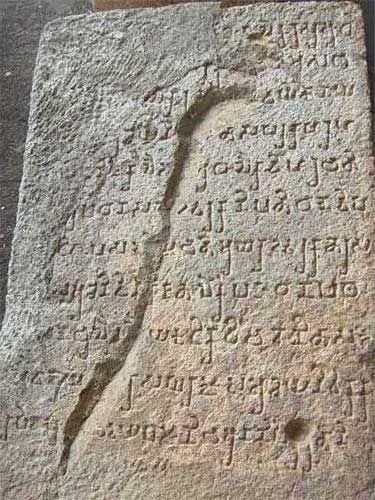

In his 250 B.C.E. Rock Edict 9, King Ashoka required his subjects to treat dasas and servants with proper courtesy. In classical Sanskrit drama such as the Mrichhakatika of Shudraka (c. 5th century C.E.), one finds characters like Madanika, who in spite of being a agharbha dasi (servant from birth), still plays a significant role as the friend and companion of the female protagonist, Vasantasena, herself a well-respected ganika (courtesan).

Overall, it appears that dasas were so gently treated that travelers like Megasthenes (c. 350 – c. 290 B.C.E.), who were familiar with the harshness of slavery in other countries, did not even recognise any slavery in India.

“This also is remarkable in India, that all Indians are free, and no Indian at all is a slave. In this the Indians agree with the Lacedaemonians. Yet the Lacedaemonians have Helots for slaves, who perform the duties of slaves; but the Indians have no slaves at all, much less is any Indian a slave.”

– Megasthenes, Indica

Although dasas are mentioned in various Hindu texts beginning with the Rigveda, it appears from multiple sources that any large-scale bondage of people was not widely practiced and, apart from a few aberrations, the treatment of dasas was gentler and more humane in ancient and classical India when compared to the situation of slaves in other contemporary societies. The classical Indian economy did not depend on slavery and there were no slave markets. One can contrast this with the subsequent legitimisation of slavery in Christianity, Islam and Communism. Both Christianity and Islam approved of enslaving those who did not subscribe to their respective faiths, also known as infidels. Christian nations were the leading allies of the Islamic slavers during the 17th to 18th century zenith of the slave trade. Most Christians and Christian Churches continued to justify slavery until the American Civil War of the 1860s. In the modern era, Communism and Fascism carried on the practice of enslaving millions of people in places like Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union etc. during the 20th century.

Slavery during Islamic rule

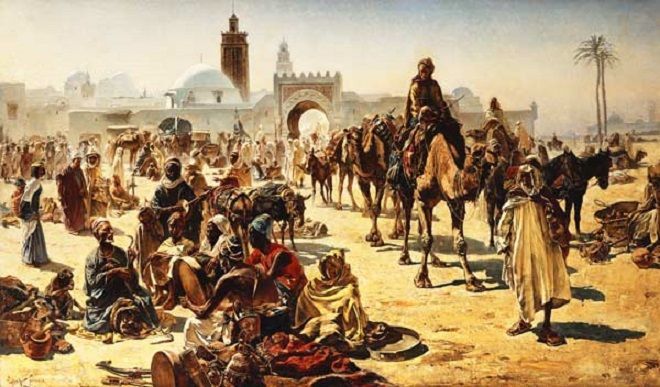

In medieval India, real slavery took root with the onset of Islamic rule over parts of the Indian subcontinent. Beginning with the Arab invasion of Sindh, continuing with Mahmud Ghaznavi’s marauding assaults and the subsequent rule of the Mughals etc., slavery was a major feature of the Islamic period and contributed largely to the growth of the Muslim population of India. During battles, captives were terrorised as towers of skulls of the killed were raised by the invading armies. After being restrained by binding their hands and feet and being kept under the control of armed guards, most of the traumatised prisoners eventually submitted and were made into slaves, converted, sold or made into menial servants.

During Muhammed bin Kasim’s 710 C.E. Arab invasion of Sindh, several thousand women were enslaved. He sold some of these female slaves of royal birth, and some he presented to others. Selling of slaves was a common practice. In Brahmanabad – later renamed as Mansura, the capital of Sindh under Arab rule – between 6,000 to 16,000 fighting men were killed, and their families enslaved. The garrison in Multan was massacred and families of around 6,000 commanders and soldiers were enslaved. In Sindh, female slaves captured after every campaign of the marching army, were forcefully converted to Islam and married off to Arab soldiers who settled down in colonies founded in places like Mansura, Kuzdar, Mahfuza and Multan.

During Mahmud Ghaznavi’s invasion of 1000 C.E., hundreds of thousands were captured as slaves. After the battles at Waihind, Peshawar, Kannauj and other places, around 750,000 slaves in total were carried back to his capital of Ghazna where there were so many Hindu slaves that the capital became like a city of India. Merchants, known as dalal-i-bazar, came from various places to purchase the Hindu slaves. Ultimately, the surrounding lands of Mawarau-un-Nahr (Transoxiana), Iraq and Khorasan were flooded with thousands of Indian Hindu slaves.

In later times, the Mughals had warm affinities with the Ottoman empire in Turkey and the Safavid empire in Persia. They regularly exchanged slaves and reinforced each other’s positive perception of slavery. Over time, those Hindus who were captured during battle and those Hindu women who were captured as part of the practice of bride-snatching etc. were all converted to Islam.

Many peasants, Rajas and Zamindars fled into the forests to escape enslavement and conversion. These Hindus continued their armed resistance to Islamic rule from the forests. After many generations of dwelling in the jungles, these former peasant and zamindar communities were reduced to the position of scheduled castes, scheduled tribes and backward classes. For example, many Parihars and Parmars, formerly belonging to the Rajput class, became part of the backward classes and were later even persecuted as “Thuggees” during the British colonial period.

Sex slavery was also widely practiced in the Muslim-ruled territories. To avoid enslavement, countless Hindu women committed Jauhar or mass ritual suicide. Inside the harems of Islamic noblemen, wives, mistresses and slaves all lived together. Eunuchs were appointed as guards of these harems. Wives and mistresses had the right to quarrel with or upbraid the husband but did not have the right to free slave girls under Islamic law. During the 18th century, with the rise of the Maratha Empire and the decline of the Mughals, in their effort to earn a livelihood, many former slave girls adopted the profession of dancing girls or prostitutes. Also, many of the former eunuch guards of the harems became hijras. The eunuch and transgender community of hijras continue to be part of today’s society in the Indian subcontinent.

How Hindu conquerors behaved in foreign lands

After having seen the barbaric behavior of some Islamic conquerors, one can compare it with the advice given by Kautilya in the Arthashastra to a king who has conquered a new territory. Having conquered another kingdom, the conquering king is advised to undertake certain obligations to bring back peace in the newly conquered territory:

- to adopt the same mode of life, the same dress, language, and customs as those of the local populace

- to follow the local people in their faith with which they celebrate their national, religious and congregational festivals or amusements

- to favour learned men, orators, charitable and brave persons with gifts of land and money and with remission of taxes

- to release all the prisoners

- to help all the miserable, helpless, and diseased persons

Historically, these principles were followed whenever Hindu kings conquered each other. Even in South East Asia, after having conquered several countries, including Srivijaya, Sumatra, Java and Southern Thailand and spreading the Hindu dharma, the Tamil Chola emperors like Raja Raja Chola and Rajendra Chola never interfered with the local customs or traditions of those places. Also, during the spread of Hindu and Bauddha dharma across several nations like China, Japan, Korea etc., none of the local traditions were uprooted. For instance, in Japan, the practice of Buddhist dharma today exists in harmony with the indigenous Shinto tradition. The dharmic traditions have always shown immense reverence to the local customs, beliefs and practices of any foreign land and tried to blend in seamlessly with them. In the Hindu or Buddhist religions, there has never been any question of enslaving or terrorising the conquered populations or destroying their culture.

Today’s situation

Bonded labour continues to be seen today in some pockets of Indian society. This is an evil practice that needs to be uprooted. The very notion of bonded labour goes against the spirit of the Sanatana Dharma which has governed Hindu civilisation for thousands of years. When a person is forced against his or her will to be a bonded labourer, it takes away the ability of such a person to fulfill their purushartha (goals of life) which is a right and duty of every human being with a conscience. Any sort of forced labour and bondage that exists thus needs to be eradicated urgently from the face of the earth.

References

- Shamasastry, R. (1915). Kautilya’s Arthashastra Translated into English

- E. Hultzsch (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka

- Megasthenes. Indica

- Hinks, Peter (2007). Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition, Volume 1

- Lal, K. S. (1994). Muslim Slave System in Medieval India

- Raza, S. Jabir (2010-2011). Hindus Under the Ghaznavids. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress Vol. 71

Featured Image: The Muslim Times