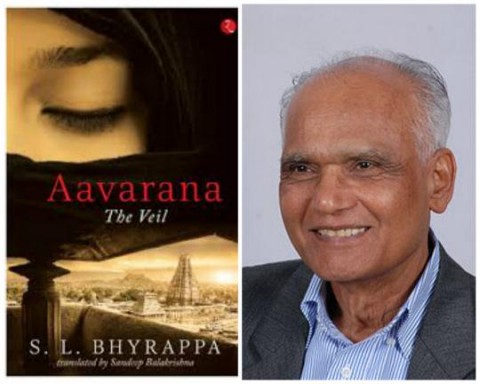

(An analysis of Aavarana: The Veil by S.L. Bhyrappa. Translated into English by Sandeep Balakrishna. Paperback: 400 pages. Publisher: Rupa Books Co., 2014. ISBN-13: 978-8129124883)

Introduction

Ostensibly a work of historical fiction, the Kannada writer S.L. Bhyrappa’s book is apt to touch raw nerves for readers of every persuasion, especially if they endure till the bitter end. Without saying so, it reminds us that the Indian national motto “Satyameva jayate naanrtam” (‘Truth alone triumphs, not falsehood’, Mundakopanishad 3.1.6) takes some character and conviction to live by, or risks being reduced to sloganeering and eventually, to irony and parody in equal parts.

Mr. Sandeep Balakrishna, who has translated the book from the Kannada original into English, richly deserves the collective gratitude of Hindu society for having brought this book to a larger reading public, potentially including foreign scholars.

Among historical novels and even history books, Aavarana is likely to stand tall for its candor and accuracy tempered by human sympathy. Few Indian historians and fewer Indian novelists have dared to approach the subject of this work, either due to a lack of the requisite erudition or for fear of political incorrectness.

The main theme of the book is the prevalent, official negationism of the less savory events and effects of the Islamic conquest of India on the Hindu psyche and society. This negationism is what the term “aavarana” literally denotes – the covering up of inconvenient facts in the service of ideology at best and expediency at worst. However, many other sub-themes are woven together in a literary style that India has known since the days of the Ramayana and Mahabharata – that of the ‘story within a story’. Dialogues between different characters and even mental soliloquies can pique the inquisitive and attentive reader into commencing new directions of investigation, just as the thought-provoking dialogues of classical works do.

The framing narrative in Aavarana is that of a modern Hindu Kannadiga woman in independent India, Lakshmi Gowda, who discards her ancestral religion in favour of what is called ‘Progressive thought’, followed by conversion to Islam for the sake of marrying a Muslim filmmaker and integrating into his orthodox family.

In this and other efforts to break free of what she considers the archaic, patriarchal and parochial mores of Hindu society, she is encouraged by an ‘eminent intellectual’, Prof. L.N. Sastri. He is of her own ethnicity, a Brahmin who leads by example, most prominently by marrying a British Catholic woman and flaunting his beef-eating in a defiant newspaper article.

Many years after her marriage, while filming at Hampi, where the ruins of the Vijayanagar empire lie strewn around, ‘mute witnesses’ (Sita Ram Goel1) to wanton destruction motivated by Islamic iconoclasm, Razia Begum Qureshi née Lakshmi Gowda starts the examination of the facts on the ground, literally and metaphorically. Here, news of the death of her Gandhian father who disowned her on her marriage and conversion decades ago reaches her. Razia, emotionally affected by the sudden turn of events, visits her natal house. An intellectually transformative event occurs when she chances upon her father’s study wherein he had accumulated a large number of books (including several by Muslim historians) describing various facets and periods of India under Islamic rule. He was apparently planning to write a book using this material, and had made copious notes, but was unable to complete the work before his death. Wanting to complete her father’s work, but not being an academic scholar herself but an artist, she decides not to write a book on history, but a historical novel based on the material available, and with scrupulous adherence to the truth. This novel is the second narrative within the book.

An eye for detail

This is a novel with a mission – to encourage Indians to think objectively about their history on the basis of primary evidence, rather than take refuge in pleasing platitudes that have metastasized into unsupportable speculations and mindless sloganeering in the service of political and ideological fashions. In this account of not one, but several intellectual journeys, Razia is the freethinker who has done a Malhotran U-turn2 in reverse, and Prof. Sastri is the distilled essence of our ‘eminent historians’ who write ‘official history’.

Bhyrappa deals very knowledgably and with great sympathy and accuracy about doctrinal matters and worldviews essential to the Hindu-Islamic encounters, not incidental to them. In the latter category of incidental matters we may include linguistic borrowings and the adaptation of Hindu art forms to Islamic tastes, the basis of the much-beloved and laboriously contrived, but nevertheless unreal, contemporary ideal of a ‘composite culture’.

The overall effect of this approach is to maintain a rare clarity of thought and a high level of detail, framing each issue in sharp relief, until the reader can disagree with the inevitable conclusions only by closing (or banning) the book. This is what the Indian secular establishment has been doing – ‘strangling by silence’3 – simply refusing to acknowledge, leave alone trying to systematically examine the literary and material evidence.

Perceptive and conscious Hindus will additionally find in this book a welcome literary revival of their hoary philosophical tradition of ‘poorva paksha’. This involves rendering the opinion of others with utmost honesty and fidelity. Each of the arguments and thoughts of the characters involved is imbued with these admirable qualities precisely because this is truly a book of essentials. As Bhyrappa writes in the acknowledgements, he spent time traveling, researching texts and interacting with people to the extent of having practicing Muslims advise him on the finer points of Islamic customs and manners. This level of research constitutes a clean and hopefully irreversible break with the harmful legacy of mindless sloganeering by Hindu religious and political leaders culminating in Gandhi’s ‘sarva dharma sama bhaava’ (equanimity towards all religions) – an opiate designed for Hindu consumption that no Muslim or Christian can subscribe to without committing a combination of social hypocrisy and doctrinal heresy.

Hindu leaders (except perhaps the late Swami Dayananda Saraswati of the Arya Samaj) have historically contented themselves with blaming fanatics among Muslims, but obstinately refrained from even the simplest study of core Islamic doctrines, leave alone analysis of the consequences of those doctrines for the Hindu society. Thus, Hindu leaders lead their followers astray by pretending to know all about Islam (and other competing ideologies) without having read any foundational texts worth the name.

Dr. Shreerang Godbole, a member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS – ‘National Volunteer Association’), exposed a major instance of self-deception among contemporary Hindu nationalists in a series of articles and some revealing correspondence4. Instances of Hindu-led, self-delusional ‘inter-faith’ exercises can be multiplied, going back to the nirguna (‘attribute-free’) strains of the medieval Bhakti movement itself and, nearer our own times, Gandhi’s obstinate attempts to remain doctrinally illiterate. Bhyrappa administers the much-needed corrective to such persistently ad hominem and ad hoc reactions from Hindus by going back to the fount, as we shall see.

Reopening suppressed facts

Aavarana also treads on territory that has been scrupulously kept out of sight in Indian textbooks, and even in much of Hindutva literature – the enslavement of Hindus by Islamic conquerors that, in the case of young male captives, was often accompanied by forced emasculation. Even a cursory review of Islamic history (e.g. the Ottoman caliphate) will indicate that the slave-taking and eunuch-making described in the book was but a local instance of a more widespread behavioral pattern. When such uncomfortable facts cannot be avoided, the standard secularist tactic is to either allege ulterior motives on the part of the informant (shoot-the-messenger or spit-and-run policy) or to creatively recast the account as an ancient instance of some contemporary social ideal.

An example of the last tactic was recently in evidence in the self-described ‘India’s national newspaper’, The Hindu. In his review of a work on the history of the Delhi Sultanate, Mr. Ziya-us-salam bemoaned contemporary homophobia and prejudice against the transgendered and neutered, saying that the Delhi sultanate was much ‘wiser’ in such matters by highlighting that Alauddin Khilji’s famous general, Malik Kafur, was both a eunuch and a converted Hindu, not a Turk. Yet, Kafur’s gender was never a point of concern for his contemporaries. All the way into Mughal times, eunuchs continued to hold important positions and to actively participate in the politics of the time5. The review concluded with a clarion call for an equitable attitude towards LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender) rights:

“In the liberal ways of the Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughals lie a few lessons for us today.”

Now, a liberal attitude towards contemporaneous LGBT individuals is unexceptionable for anyone who cares for human rights. But, the inconvenient historical fact glossed over is that Malik Kafur was surnamed ‘Hazardinari’ i.e., ‘costing a thousand dinars’. He was a Hindu boy captured as booty during Alauddin’s Gujarat campaign, castrated and eventually sold for the aforementioned dinars. Understandably, you would be hard-put to discover prejudice against eunuchs in a society that created them and valued them for their services. These facts again highlight the contemporary relevance of Bhyrappa’s investigation into the liberties one can take with historical facts, even to support valid social causes. Razia’s novel within Aavarana is in the form of the autobiography of a eunuch who was a newly-married seventeen year-old Hindu prince prior to his capture and enslavement in war, followed by forced castration.

We will let the late historian K.S. Lal have the last word on the status and role of eunuchs under the Islamic dispensation:

“The need for turning so many boys and men into eunuchs and also obtaining them from outside is obvious. The safety, security and surveillance of a large number of beautiful women in the seraglio could not be left only to female matrons. And normal healthy men could not be trusted to serve in the harem in which resided so many sex-starved young women. So the safest thing was to make men who were on duty in the harem harmless. The king also lived in the harem, and nobles and servants personally attending on him also had to be eunuchs. The cruelty entailed in this system was nobody’s concern in a despotic regime. On the other hand, it was very advantageous to the master. Once a man was made eunuch, his sensibility for manhood was dwarfed, his spirit of assertiveness destroyed, and he was perforce turned into a loyal and devoted slave; it did not matter to the master if his loyalty and devotion were fruits of compulsion. So the practice of making eunuchs went on and on under Muslim rule. If eunuchs were denied “the greatest pleasures attainable in this world”, they were compensated by sometimes performing great feats of bravery, by showing great loyalty to the master or by just piling up great wealth.

It is not the task of the historian to pity the eunuchs or condemn those who emasculated them. But pernicious was the system in which man could exploit man to this extent. It is another matter that most eunuchs perforce reconciled themselves to their lot, though cruelty and crime could go no farther than deforming and desexing of man by man. Many people suffered because of the medieval Muslim slave system, but undoubtedly the eunuchs suffered the most.”6

Thus, the signal merit of Aavarana lies in the scrupulously faithful characterization of not only historical events and persons, but also the contemporary secularist Indian-Islamic axis and praxis. The secularist technique of maintaining hegemony by limiting access to relevant information or depending on the ignorance of their audience is a technique that is long past its expiry date.

Most damagingly, in Bhyrappa’s hands, the prompt juxtaposition of the lofty, yet shifty, Indian secularist ex-cathedra proclamations and ‘analyses’ with the inconvenient historical data leaves the reasonable reader in no doubt as to how silly Indian secularism can be when it is not actively poisoning Indian society. Thereafter, only the wilfully duplicitous or compulsively self-deluded can keep up the charade of Indian secularism. That this simple juxtaposition could have been successfully deferred for nearly half a century after India’s independence in 1947 speaks volumes of the intellectual climate of the Nehruvian-Stalinist state that India had been reduced to, until the advent of more modern and less controllable forms of information transfer, particularly the internet.

Aavarana vividly demonstrates the truth of Arun Shourie’s assertion – ‘cut out and store their (i.e. secularists’) vituperation — in less than no time it mutates into the ridiculous.’7 These facts sufficiently account for the extreme distaste with which Bhyrappa is being viewed by sections of the Kannada (secular) literary establishment.

Even more problematically from the Indian secularist viewpoint, Bhyrappa has not fallen into the vulgar error of blaming Muslims as a community. Going deeper than the compilation of various historical accounts, he highlights the doctrinal foundations of Islam – the Koran, the Hadiths and the Sunnah. These foundational texts of Islam, we find, in and of themselves, sufficiently account for the attitudes and behavior of conscious Muslims towards Kafirs and their practice of Kufr. In less politically correct times, this was an obvious fact admitted as much with pride by Muslim historians themselves, and is still being repeatedly highlighted by the so-called ‘radical’ Islamic groups and regimes, but it bears restating in the current climate of gratuitous, and often, professional obfuscation.

Academic corruption and the Indian progressive/secular/Marxist intellectuals

Aavarana will (or should) make every academic (and not only in the social sciences) sit up and think, if not cringe: Absolute truth may well be distant, abstract, even unattainable, but are they doing violence to more mundane, observable facts in blind devotion to cherished theories? And, what about the hefty governmental grants and patronage that are employed to these ends? Do academics that make honest errors bother to correct themselves?

However, Aavarana’s most ominous and troubling question about the academic establishment (especially its Indian avatar) is left unstated, so let us make it explicit.

Now, right or wrong, at least the temple-breakers and Kafir-enslavers had the honesty to admit the reality of their intentions and actions, and acknowledge their rootedness in doctrinal convictions. Do our academics have any such principles, or do they hunt with the hounds and run with the hare as it suits them? Are they rank opportunists who fall into one of the four categories of ‘eel-wrigglers’ enumerated by the Buddha8?

One can only shake one’s head with cynicism when we find Prof. Sastri eating beef as a gesture of defiance one day, but happily agreeing to give a discourse on the wisdom of cow protection for a Gandhian organization on the next. This writer witnessed in person an ‘eminent historian of India’ waving off Timur’s admission of Islamic motives in his autobiography by censuring the British historians who documented this (Eliot and Dowson) for their ‘imperial-colonial motives’ (see: shoot-the-messenger and spit-and-run above). So, I can tell from experience that Prof. Sastri is pretty much true to type, as are the outnumbered and organizationally outmaneuvered Hindu activists who try to call the secularist bluff at ‘progressive’ seminars.

But then, Prof. Sastri is also the true hero of this novel. Without his undeniable erudition and command over the English language that are ‘gainfully employed’ to justify anything ‘progressive’ with aplomb, to suppress key facts and wilfully indulge in outright fabrication when mere misinterpretation won’t suffice, all in the name of secularism and communal harmony (see: eel-wriggling, above), the central problem of the novel – the veiling (Aavarana) of the truth in history-writing – would not even exist. Verily a case of philosophia ancilla theologiae (pace St. Thomas Aquinas)! In passing, we also note that Yoginder Sikand’s confession about the lucrative and prestigious progressive academic-activist circuit9 eerily corroborates Bhyrappa’s characterization of Prof. Sastri, so that this book is well-nigh ‘certified’ too by high authority, if such were required. This only enhances Bhyrappa’s standing as a careful and conscientious gatherer of facts and as a consummate storyteller who weaves them into a coherent narrative.

Non-Indian academics and assorted “India/Hinduism experts” should also take Bhyrappa’s unstated warning seriously. From their positions of prestige, they should not mindlessly first swallow, or worse, unthinkingly propagate, notions fed to them by their native informants (or ‘academic collaborators’) in the Indian secularist establishment. They need to engage directly with primary data to make sure that they are not being fed cock-and-bull stories sugar-coated with fashionable ideologies by the allegedly progressive secularists of India. More importantly, for their own sakes, they also need to get their act in order and function with at least some appearance of disinterested objectivity, if they are to salvage what is left of their integrity

On the Hindu side, Ram Swarup’s words bear reiteration if Hindus are not to discredit themselves in turn by going to the opposite extreme and disregarding all academic researchers (even those hostile to Hinduism) as a matter of policy:

“…But there were also others (British historians) who had genuine curiosity and in spite of their pre-conceived notions, they tried to do their job faithfully in the spirit of objectivity. In the pursuit of their researches, they applied methods followed in Europe. They collected, collated and compared old manuscripts. They deciphered old, forgotten scripts and in the process discovered an important segment of our past. They developed linguistics, archaeology, carbon dating, numismatics; they found for us ample evidence of India in Asia. They discovered for us much new data, local and international. True, many times they tried to twist this data and put fanciful constructions on it, but this new respect for facts imposed its own discipline and tended to evolve objective criteria. Because of the objective nature of the criteria, their findings did not always support their prejudices and preconceived notions. For example, their data proved that India represented an ancient culture with remarkable continuity and widespread influence and that it had a long and well-established tradition of self-rule and self-governing republics, and free institutions and free discussion.” 10

An example of negationism by a non-Indian academic is that of Richard Eaton who documented cases of temple destruction by Sufis in the book, Sufis of Bijapur11. However, flying in the face of facts, Eaton has also written apologetics for Islam. One would think that, being a free American citizen and an academic with tenure at the University of Tucson, Arizona, he would have robustly stood by his scholar’s prerogative to unearth inconvenient facts with complete honesty, and left it to the distant Indian society to deal with these facts as best as it might. In fact, this is routinely done in every case of ‘drain inspection’ carried out on the ills of Hindu society.12

Rather, Eaton laboriously tried to establish a false parity between Hindu and Islamic kings by highlighting an imagined ‘continuity’ in temple destruction, citing pre-Islamic instances of rival Hindu kings taking away images of deities during conquest for re-installation in their own temples13.

This ‘continuity’ is, of course, entirely in the eye of the scholar. A little thought and common sense will indicate that the Hindu kings’ appropriation of images worshipped by their rivals is in no way equivalent to the Islamic act of carrying away Pagan idols where their eventual fate is not respectful re-installation and worship in the Islamic Sultan’s personal shrine, but melting down for precious metals, or breakage and embedding into doorsteps so that they could be subjected to desecration by the faithful for the foreseeable future. These indignities are in addition to disrupting Pagan idol-worship at the original site, which is not the case with pre-Islamic India, where the defeated Hindu king was free to re-commence worship of a different image. Eaton’s (and others’) historical skullduggery rooted in a studied refusal to examine Islamic doctrine for reasons underlying Islamic behavior have been documented and critiqued at length by Koenraad Elst in his book Negationism in India14.

On the Pagan response to prophetic revelatory religions

Bhyrappa ends his work on a very tantalizing note that has not been much remarked upon even in favorable reviews as far as I could see – Vivekananda’s attempted yogic analysis of wahi – the process of divine revelation in Islam. He also offers instances wherein Hindu thought categories are used to analyze events, something that is hardly met with even in Hindu-friendly literature.

So far, the Hindu revivalist author Ram Swarup has been the only Hindu to interpret the process of prophetic-monotheistic revelation from a yogic viewpoint15. On the secular front, the Dutch scholar Herman Somers, a former Jesuit priest and a qualified psychologist had unearthed psychopathological syndromes associated with many instances of prophetic revelation in the Bible, including that of Jesus. His findings, inaccessible to those who don’t know French or Dutch (including this author), have been ably summarized by the Belgian Indologist Koenraad Elst in his book Psychology of Prophetism16.

Hindus, especially their assorted, well-funded gurus, would do well to read these books and develop their own informed critique of other religions at deeper, doctrinal levels and desist from misleading their families and flocks with misinformation in the guise of ‘promoting religious harmony’. This intellectual shoddiness and poverty of thought has been termed ‘radical universalism’ by Frank Morales, a Hispanic-American convert to Srivaishnava Hinduism17.

Bhyrappa has therefore performed a signal service to Hindu society by taking his readers on a whirlwind tour of both the historical and doctrinal aspects of the Hindu-Islamic encounter, while scrupulously avoiding the pasting of collective or inherited guilt on contemporary communities. It is obvious that durable peace between these two communities will require a lot more than mere political correctness and formal niceties involving soppy, Bollywood-style inter-religious love stories, lavish Mughlai food or florid Urdu poetry, not to mention candlelight fairs at the Indo-Pak border post at Wagah.

Conclusions

Aavarana is a literary efflorescence (detractors would like to say recrudescence) of what the likes of Sita Ram Goel1, Arun Shourie18 and Koenraad Elst14 have painstakingly achieved for serious history writing over the last few decades – an exposé of the official Indian negationism of the career of Islam in India, as well as the legal censorship of all doctrinal critiques of Islam that has prevailed for most of independent India’s recent history. The denial of asylum to the Bangladeshi atheist-feminist writer Taslima Nasreen and the denial of an Indian visa to Salman Rushdie by the Indian government are merely two notable manifestations of this self-imposed censorship.

Of course, two can play this game of officious legality and offended religious sensibilities. Thus, the Hindus, in their turn, filed cases in the courts against the Muslim painter M.F. Hussain and the Jewish-American academic Wendy Doniger, on the grounds of offending their religious sentiments. As a result of legal harassment, M.F. Hussain chose to end his days in exile in Qatar and Penguin India, the publishers of Doniger’s book The Hindus: An Alternative History, opted for an out-of-court settlement, pulping all the unsold copies of Doniger’s book and refraining from releasing any new copies in India.

Interestingly, Doniger could not resist doing her own bit of veiling – Aavarana – in the wake of this controversy. Referring to Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code, under which Penguin India were hauled to court in the first place, she wrote as follows in a statement in Outlook magazine:

“They (Penguin India) were finally defeated by the true villain of this piece – the Indian law that makes it a criminal rather than civil offense to publish a book that offends any Hindu, a law that jeopardizes the physical safety of any publisher, no matter how ludicrous the accusation brought against a book19.”

The innocent reader may justifiably conclude that this villainous law is preoccupied solely with offended Hindu sentiments, something that would befit the secularist scarecrow of a rabid Hindu theocracy. However, on closer inspection, the British-era law, though intended primarily to pre-empt Islamic riots that erupt with monotonous predictability on grounds of outraged religious sensibilities, takes adequate care to use neutral language befitting an even-handed concern for all groups:

“Whoever, with deliberate and malicious intention of outraging the religious feelings of any classof citizens of India (originally ‘British India’)…20

Yes, any class of Indian citizens, not just Hindus – potentially every religious, linguistic, regional, vocational, sectarian, or caste grouping. Suppressio veri, suggestio falsi, and that too by an American academic, the “Mircea Eliade Distinguished Service Professor of the History of Religions; also in the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations, the Committee on Social Thought, and the College…21” no less.

Given such instances, Bhyrappa’s concerns about the truth being hidden or conveniently diminished by our ‘eminences’ holding forth from their lofty pulpits are fully warranted. Time and again, the Indian secularist establishment and their foreign fellow travelers have painted themselves into inconvenient corners, often with their own weapons used against those very cherished humanistic values and ideals whose custodianship they have arrogated to themselves.

Secularists, especially Bhyrappa’s fellow Kannadigas like Girish Karnad, Aravind Adiga and U.R. Ananthamurthy, have concentrated their ire on Bhyrappa, either disowning him or condemning him. Aravind Adiga characterizes Bhyrappa as a novelist ‘in search of an ending’ and one who is ‘in danger of having a fanbase composed entirely of bigots’ 22. Indeed, the ‘danger’ exists precisely because of the falsification and fabrication that has become de rigueur in the teaching (or preaching?) of Indian history1, 14, 18,. Six years ago, when asked about his (Adiga’s) own choice to portray the crushing poverty of India in his novel, Adiga proclaimed that ‘provocation is one of the legitimate goals of literature’23. Clearly, he is not interested in extending that legitimacy to Bhyrappa now. Another instance of the famed ‘Aavarana’?

The only way to ‘save’ Bhyrappa, if the likes of Adiga sincerely want it, is to have the snooty ‘eminences’ dismount their high horses, and make amends for their chronic negationism, and allow for glasnost in the critiques of ‘minority religions’. And, a truly secular way to combat the feared ‘Hindu bigots’ would be to address their legitimate contemporary concerns regarding Islamic violence as well as treat the historical record of Islam in India in a more professional manner than has been in evidence so far.

Of course, none of this is possible without at least a tangential critique of Islamic doctrine, a move fraught with a real, as opposed to an imaginary shot (pun intended) at martyrdom that every secularist knows only too well.

There are more vital and interesting facts in this novel, especially about traditional Hinduism, the views on conquest and polity in the Dharmashaastras, historical material on Aurangzeb’s times and policies and so on, that have not been purposely touched upon by this reviewer to avoid ‘spoilers’.

Bhyrappa deftly has Razia write a bibliography within Aavarana, which indicates the extent of research and reading he has undertaken. Therefore, aside from the dominant theme of the Hindu-Islamic struggle, Hindus can learn much about their own heritage, legacy and history from Aavarana, and the bibliography can serve as a starting point for further inquiry. In addition to fulfilling its literary function as a novel on a historical theme using classical Hindu literary devices, Aavarana can reasonably double as a popular introduction, a Berlitz if you will, for lay Hindus to the landscape of what may well develop into an academic specialization in its own right – ‘Indian secularism studies’.

The elephant herd in the already crowded room – recurring street riots, petty violence and arson, not to mention chronic acts of terrorism against the Hindu populace of India, often aided and abetted by the Indian Muslim enclave of Pakistan – cannot be wished away by platitudes alone. This book should initiate introspection among serious and observant Hindus and Muslims about the doctrinal foundations of their respective religions.

Under the circumstances, resolving to consciously eschew the less humane aspects of religious doctrines and practices might seem a reasonable course of action to adopt. However, upon such objective scrutiny and reform, person- and history-centric religions like the Abrahamic ones24 will probably end up all the worse for the wear, as compared to Pagan ones. And therein lies the rub: Why should anyone willingly choose inconvenient truths over beautiful secular constructs? A Pagan myself, I may tentatively suggest an answer culled from an Abrahamic text – ‘And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free’25.

All right-thinking (in the sense of ‘decent’ not ‘politically conservative’) Hindus and Muslims should be thankful to Bhyrappa for holding up a mirror to their attitudes and mores, unflattering though the reflections may be on occasion. After all, to err is human, but not to realize one’s error when so clearly highlighted would only qualify as incorrigible obstinacy or sheer perversion. Though hardly remarked upon by inimical secularists, a relentless focus on fact and truth constitutes the truly ‘fanatic’ aspect of this singular novel. Posterity will recall it as a pioneering literary contribution to the Hindu-Islamic narrative from the Hindu side or, to put a truly secular slant on it, a sorely needed infusion of reality into the fashionable, not to say lucrative, business of inter-faith dialogue in India.

Notes and References:

1. Hindu temples: What happened to them (vol.1). A preliminary survey. (1990). SR Goel (ed). pp. 41-154. Voice of India, New Delhi, India. http://voiceofdharma.org/books/htemples1/ch10.htm

2. Dey A. (2006). Rajiv Malhotra’s “U-turn theory.” http://www.deeshaa.org/2006/02/16/rajiv-malhotras-u-turn-theory/

3. Elst K (2001). India’s only communalist: A short biography of Sita Ram Goel. http://koenraadelst.bharatvani.org/articles/hinduism/sitaramgoel.html

4. Time for stock-taking: Whither Sangh Parivar? (1997). Goel SR. (ed.) Voice of India, New Delhi, India.

5. Ziya-us-salam. In wiser days. In The Hindu, April 25, 2014. http://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/in-wiser-days/article5947289.ece

6. Lal, KS (1994). Muslim slave system in medieval India, ch. 9. Aditya Prakashan, New Delhi, India. http://voiceofdharma.com/books/mssmi/ch9.htm

7. Shourie A. Cut, paste and preserve their calumny. In The Observer,January 22, 1999. http://arunshourie.voiceofdharma.com/print/19990122.htm

8. In the Brahmajala Sutta the Buddha refers to ‘ascetics and Brahmins’ who equivocate as those who ‘wriggle like eels.’ http://buddhasutra.com/files/brahmajala_sutta.htm

9. Sikand Y. Why I gave up on ‘social activism.’ In Countercurrents, April 19, 2012.http://www.countercurrents.org/sikand190412.htm

10. Swarup R. Historians versus history. In The Indian Express, January 15, 1989.http://www.voiceofdharma.com/books/htemples1/ch6.htm

11. Eaton RM. (1978). Sufis of Bijapur, 1300-1700: Social Roles of Sufis in Medieval India. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.A.

12. This refers to Gandhi’s characterization of the racialist and anti-Catholic historian Katherine Mayo’s (in)famous book Mother India as being a ‘the report of a drain inspector.’

13. Eaton RM. Temple desecration in pre-modern India and Temple desecration and Indo-Muslim states. In Frontline, December 22, 2000 and January 5, 2001. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00islamlinks/txt_eaton_temples1.pdf

http://ftp.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00islamlinks/txt_eaton_temples2.pdf

14. Elst K. (2002). Negationism in India: Concealing the record of Islam. Voice of India, New Delhi, India. http://koenraadelst.bharatvani.org/books/negaind/

15. Swarup R (1982). Hindu view of Christianity and Islam. Voice of India, New Delhi, India.

16. Elst K (1993). Psychology of prophetism: A secular look at the Bible. Voice of India, New Delhi, India. http://koenraadelst.bharatvani.org/books/pp/

17. Morales, FG. All religions are not the same. The problem with Hindu universalism, a critique of radical universalism. In Hinduism Today, July/August/September 2005 issue. http://www.hinduismtoday.com/modules/smartsection/item.php?itemid=1424

18. Shourie A (1998). Eminent historians: Their technology, their line, their fraud.ASA Publications, New Delhi, India.

19. Doniger W. I do not blame Penguin Books, India. Statement in Outlook, February 11, 2014. http://www.outlookindia.com/article/I-Do-Not-Blame-Penguin-Books-India/289473

20. The Indian Penal Code. Of offences relating to religion (Chapter XV). Note that the chapter itself refers to ‘religion’ not specifically ‘Hinduism.’ http://districtcourtallahabad.up.nic.in/articles/IPC.pdf ,

21. Quoted verbatim from the official website of Prof. Wendy Doniger at the University of Chicago. http://divinity.uchicago.edu/wendy-doniger

22. Adiga A. A storyteller in search of an ending. In Outlook, March 11, 2013.http://www.outlookindia.com/article/A-Storyteller-In-Search-Of-An-Ending/284084

23. Adiga, A. Provocation is one of the legitimate goals of literature. Interview with Vijay Rana, In The Indian Express, 18 October 18, 2008http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/-provocation-is-one-of-the-legitimate-goals-of-literature-/374718/0

24. Malhotra R. Dharma Bypasses ‘History-Centrism.’ Published June 13, 2013.http://www.speakingtree.in/spiritual-blogs/masters/philosophy/dharma-bypasses-and historycentrism

25. The Bible. John 8:32 (King James Version). Lest I should be accused of indulging in radical universalism and aavarana myself, I hasten to add that the original context of the statement has nothing to do with knowing objective or cosmic truths. The ‘truth’ referred to is simply Jesus’ reiteration to his Jewish followers that he was indeed their promised messiah. But the rhetorical impact is significant nevertheless. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage