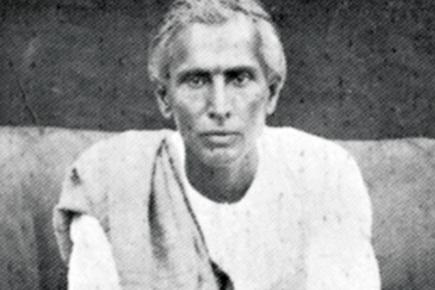

We are often disheartened to hear news of abject poverty, mistreatment of women, as well as social injustice flashed around in newspapers. These kinds of news give rise to the question: which way this nation is going? That question over the decades has prompted great minds to produce thought provoking literature, which either gives a frank display of these impediments or serves as astute commentary on such situations. Yesterday marked the birth anniversary of one such thought provoking and immortal litterateur named Sharat Chandra Chatterjee.

Fortunately a huge section of Indians know of him, but unfortunately for the wrong reasons. To these Indians he is the one who has penned novels like Devdas and Parineeta, both of which have been turned into cinematic blockbusters.

It is ironic that while the cinematic adaptations of his novels have generated huge profit, the long deceased Sharatbabu (as he was affectionately called) spent his entire life in dismal poverty. Today we pay our tributes to this great craftsman of words.

Early Life

Sharat Chandra Chatterji was born on 15 September1876 in the village of Devanandpur in Hooghly district, West Bengal. The Chatterji family was monetarily insolvent, and it was for this reason the family members depended on other relatives for financial support. Since his father was employed in Bihar, Sharat along with the rest of the family resided with his paternal uncle in Bhagalpur. However, the recurrent variation of the family’s fiscal circumstances led to a number of school changes for young Sharat who received his formal education in Bhagalpur before clearing the entrance exam and attaining admission in Tejnarayan Jubilee College in 1894.

While in college, Sharat got enchanted with great works of English literature such as Charles Dickens’ “Tale of Two Cities” and “David Copperfield”, Shakespeare’s ‘Macbeth’ and ‘Hamlet’ among others. But Sharatbabu’s greatest inspiration for writing was his father’s incomplete and unpublished literary work (some scholars maintain it was supposed to be an autobiography).

While the budding writer was looking motivation, tragedy struck his life as his mother passed away in 1895. And if that was not enough, Sharat had to drop out of college the following year due to financial troubles, which forced his father to sell the family home in Devanandpur at a very minimal price. The entire family then settled down in Bhagalpur, where Sharat met a number of people who played an important role in his writing career.

Due to disagreements with his father, Sharatbabu decided to leave Bhagalpur to pursue his own dreams. After wandering with a party of Naga sadhus, he went to Muzaffarpur in 1902. But tragedy again pulled him back to Bhagalpur as his father passed away during that time.

Career as a novelist

Following his father’s death, Sharatbabu traveled to Myanmar in 1903. There he found employment as a clerk, but the living conditions were not favorable causing him to return to India. Before his departure he submitted a short story for a prize competition under his uncle’s name, Surendranath Ganguli, which won the first prize in 1904.

In 1906, Sharat Chandra married Shanti Devi and the couple had a son in 1907. But it seemed as if his only true companion was tragedy–both his wife and son succumbed to plague and died in 1908. To fill this miserable void, Sharatbabu immersed himself in studying politics, philosophy, psychology, and history. But on being coaxed by his well-wishers, Sharatbabu married his second wife Mokshada in 1910.

After struggling with some odd jobs, Sharatbabu found a stable occupation in the accounts department of Public Works, where he served until 1916. Post 1916, he started to write on a regular basis and his works were published in all well-known Bengali magazines. This period saw the transformation of Sharat Chandra from a relative unknown to a remarkable novelist.

Most of his novels were known for their female protagonists, who hailed from all walks of life, whether it was the Empress Bijoya, the fearless leader Bharati, the licentious yet virtuous Chandramukhi, and of course the innocent and self-reliant Lalita. Sharatbabu eschewed the stereotypical image of women as constructed by the then society, giving them a fresh breath of life. Sharatbabu’s ladies dared to question social norms and even went ahead and blew them up, making way for a whole new social order. According to many literary critics, Sharatbabu dreamt of a civilization to be wholly composed of feminine understanding.

Participation in Sociopolitical issues

During the merger of the Khilafat Struggle with the Swadeshi movement in the 1920’s, many Bengali Congressmen asked for the advice of Sharat Chandra on the Hindu-Muslim communal issue. Being well read in the history of India, Sharat Chandra gave a lecture titled ‘Bortoman Hindu-Musalman Somosya’. Citing relevant and reliable sources, he explained to the Congress leaders that the unity of Hindus and Muslims was impractical in the ways they were trying, and the Khilafat agitation and Indian independence struggle should not be merged. Although Sharatbabu respected Mahatma Gandhi as a person, he was against Gandhi’s view of Hindu-Muslim union ‘at any cost’. In his own words:

Mahatma thought that we would not be able to win Independence unless Hindus and Muslims were united. He and his followers have cried themselves hoarse to rub it in. It is nothing but madness. Mahatma’s Khilafat movement does not make any sense. India has no affinity with Turkey; not more than one in a thousand or a million Hindus may be said to have some knowledge of that country. So Hindus have no reason to join the Khilafat movement. Its sole purpose is to bribe the Muslims into the Indian Independence movement.

He argued that the Congressmen should instead tirelessly work for unity within the Hindu community by putting an end to the evils of caste discrimination. To do his bid in strengthening the Hindu community, Sharatbabu often joined hands with the members of the Brahmo Samaj and Ramakrishna Mission in their campaign for widow remarriage, intercaste marriage and other social reform activities.

Many modern day scholars have at times accused Sharatbabu of being communal for his ‘Bortoman Hindu-Musalman Somosya’ lecture. But these critics forget one of his seminal works titled ‘Mahesh’ where the protagonist is a poor, honest Muslim farmer named Gafur who faces discrimination from elite Hindu landlords. When it came to poverty, Sharatbabu had no preference for any community. In the words of renowned historian RC Majumdar:

I don’t know of any other Bengali novelist who has evoked, before Sharatchandra, our sympathy for those who have lost everything of value in life. Besides, his realistic portrayal of the village society has not been surpassed.

Death

Plagued by the maladies of the liver, Sharat Chandra began to slowly withdraw himself from public activities. He would make infrequent appearances in literary functions organized by his well-wishers. Finally on 16 January 1938, one of Bengal’s greatest novelists breathed his last.

As mentioned earlier, most of India knows Sharat Chandra as the author of Devdas and Parineeta. However, on the occasion of his birthday I hope all of us make the attempt to read his other equally important works which are thought-provoking, humane, and even revolutionary.

Perhaps the best way to conclude this is to listen to a tribute given to Sharatbabu by the late Bhupen Hazarika in the form of a melodious Bengali song:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EhsjS-GTA0w