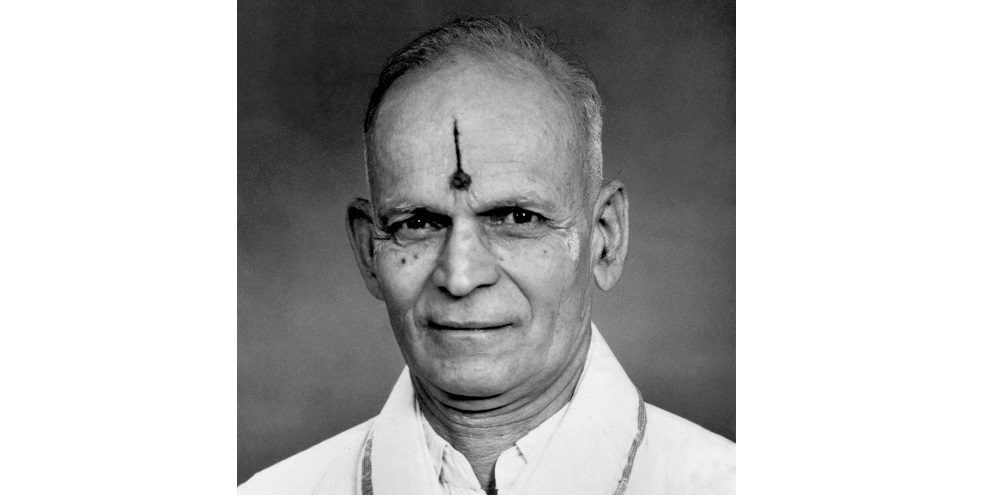

When my grandfather Shri G.K. Timmanacharya retired in Bengaluru in the year 1949 after amassing much respect and love for his work as an educator, little did he know that the most exciting phase of his life was about to begin. But, I am getting ahead of the story.

Born on December 4, 1894, my grandfather (popularly called GKT) went on to specialise in Sanskrit grammar just like his father, his grandfather and generations before him. They were all called Vaiyakarnis or Sanskrit grammar specialists and belonged to the lineage called Arvattu Vokkalu with roots in Ahichhatra (near modern Bareilly in the state of Uttar Pradesh) from where their ancestors migrated to Karnataka on the invitation of Kadamba king Mayurasharma (also called Mayuravarma). These scholars were invited to settle in Karnataka in the 4th century CE in order to teach and spread Dharmic learning. My great-grandfather Shri G.V. Krishnacharya was a highly respected literary figure – author of many books in Kannada and Sanskrit as well as a mentor to Kannada scholars who went on to achieve national fame such as the iconic D.V. Gundappa.

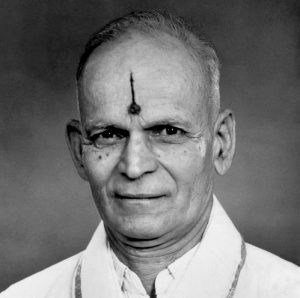

Very early in life, GKT memorised Amarakosha, the famous Sanskrit thesaurus as well as Siddhanta Kaumudi. Despite living in the shadow of his illustrious father and the obvious comparisons, he went on to make a mark of his own. When he joined Central College, Bangalore, his father was a professor in the same college. GKT loved dramatics and is said to have taken to it like a fish to water. He learned English under the guidance of Professor J.G. Tate from Scotland who had taught other stalwarts of Mysore state such as Shri Navaratna Rama Rao. For obtaining his M.A. and B.T. degrees he chose Mysore University. GKT was deeply influenced by his professors such as Dr S. Radhakrishnan (who later became President of India), Prof A.R. Wadia, Prof N. Hiriyanna and Prof Radha Kumud Mookerjee.

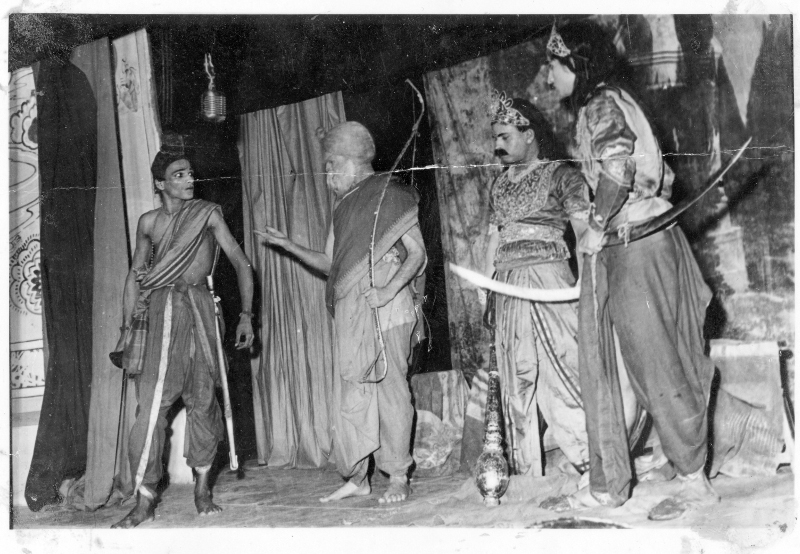

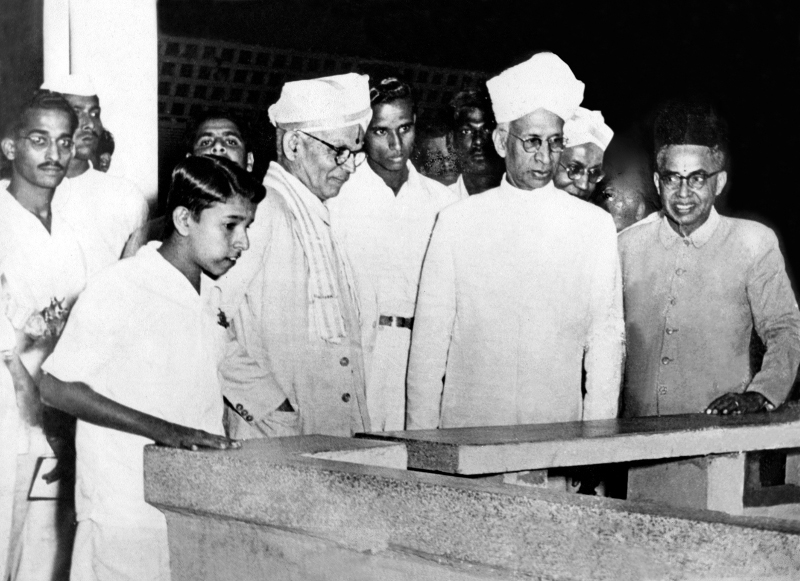

Dr S. Radhakrishna, the President of India (2nd from right) flanked by Shri G.K. Timmanacharya (3rd from right) and Shri K. Seetharama Rao (extreme right)

When he was the Principal of Chamrajendra Sanskrit College, Bengaluru, GKT worked hard to make Sanskrit popular by pushing for incentives in the form of scholarships and prizes. Many students joined the college because of his efforts. As Inspector of schools, he tried to improve the condition of Sanskrit Pathshalas throughout the state of Mysore and motivated Sanskrit Pandits. Such was his renown that sometimes letters marked with just his name followed by “Bangalore” would reach him without fail.

Regular Sandhyavandana and Yoga Asanas kept my grandfather in fine physical health. He exuded positivity wherever he went. Students simply adored him as much for his teaching as for his well-groomed, attractive appearance. The good looks were hereditary. Author D.V. Gundappa has mentioned students who were magnetically pulled in to attend Garani Krishnacharya’s (my great-grandfather’s) classes because of his milk-white complexioned handsome looks.

GKT was the main provider for his family consisting of a dear wife (my grandmother) and seven children, all of whom he doted on and wrote loving letters to whenever they were out of town. Every evening, he tutored students at home after returning from work. He wrote a number of books to help learners of Sanskrit such as a grammar book and Kannada translations of Amarakosha, Pratima Natakam, Abhijnana Sakuntala and Gajendra Moksha.

When it was time to retire, GKT still had many responsibilities to fulfil. Not all his children had completed their education, nor settled into married lives. So he joined Acharya Paathshaala as Principal. Later, he also took up a professorship at the iconic National College in Bangalore.

It was at this time after working for 30 years that my grandfather got the most interesting job offer of his life. A well-known hotelier Shri K. Seetharama Rao who owned the Dasaprakash chain of hotels wanted an in-house tutor to teach his children in Madras (today’s Chennai). Shri Rao, who was also a philanthropist and publisher wanted a teacher who would oversee the upbringing of his children. He wished that his children grew up to be Dharmic adults rooted in samskaras but at the same time well-equipped with the English language and the tools imparted by modern education, which would help them to successfully run and maintain their father’s businesses.

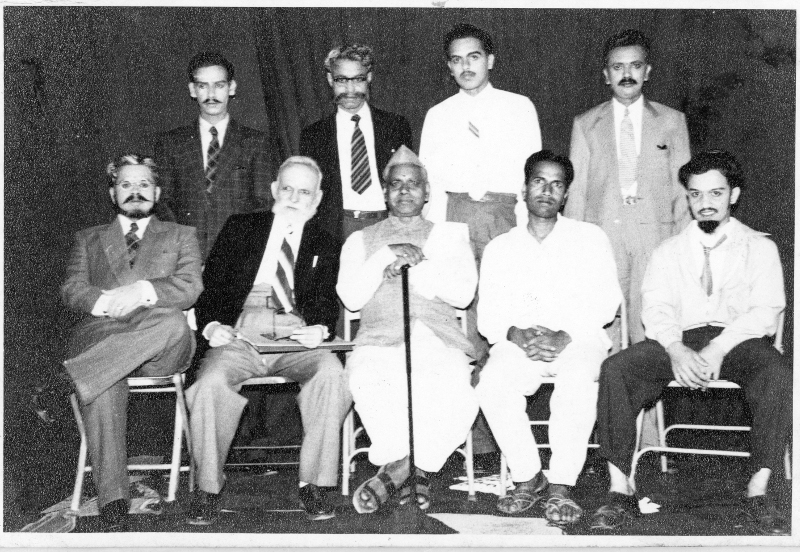

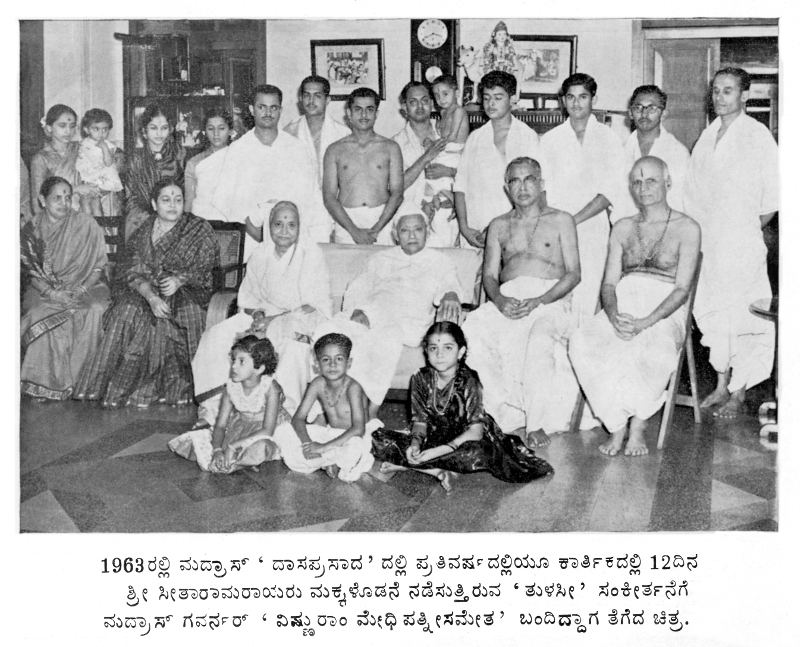

Shri G.K. Timmanacharya seated on a chair at the extreme right with Shri Seetharama Rao (2nd from right) and his family during the occasion of Tulasi Sankeertana when the Governor of Madras and his wife visited the Rao residence in 1963

It was to be a departure from the Gurukula system that Ancient India was known for. Gurukulas, as we know, were the bedrock of India’s knowledge society in ancient times. Children said goodbye to their parents and relatives after coming of age to spend years in the Ashrama of a guru (often located in forests) to imbibe a variety of subjects while also building their character. In my book, The Educational Heritage of Ancient India – How an Ecosystem of Learning Was Laid to Waste , I have described how learning and teaching was regarded as the most sacred activity in ancient India. GKT was being asked to move to his students’ home instead of the other way round.

The offer to tutor the children of Shri Seetharam Rao in their palatial Madras residence was accepted by my grandfather. My aunts and uncles were hesitant to let their father move away to a new city and start life all over again; he was the life and soul of the house. But, as my grandfather wrote poignantly years later, it was a call to his Dharma as well as kulavrutti or the family commitment to teaching, which had been followed by generations of ancestors. Genuine seekers of learning could not be turned away. Besides, GKT was excited about an additional project he had been put in charge of by Shri Rao – to manage the Dharmaprakash Press and library. Nothing could be more pleasing to my grandfather than to be in charge of producing Dharmic literature and to have a well-endowed fund to order books of his choice for stocking a library. Accordingly, arrangements were made for my grandfather to travel to Madras.

There were strong pecuniary reasons too for GKT to take up such a challenging job. Loans had to be paid off. Throughout his life, my grandfather hardly saved any money because the expenses always galloped ahead of earnings. His residence in Gavipuram, Bengaluru was filled with not just his own children but relatives who stayed for indefinite periods. His generosity was legendary; even the domestic helpers loved him.

When my grandfather arrived in Madras to join duties, he was given a room in the annexe to the residence of Shri Rao. Years later, when my grandmother joined him, a furnished house was provided within the precincts of Dasaprakash Hotel where they lived in close proximity to the residence of Shri Rao and family.

What followed next was straight out of “The Sound of Music” or “Parichay”, except that there was no romantic love angle or sundry singing on streets. Imagine a scenario where a coach is entrusted with the task of teaching a bunch of children who are most unhappy to be saddled with yet another controlling authority. Growing up under the watchful eye of an strict disciplinarian father, some of the older children had become belligerent and defiant. All that was to change.

GKT was a child at heart. When he played with children, he would forget he was an adult. Whether he was with toddlers or teenagers, he could match his wavelength with them in a heartbeat. Ever-eager for adventure or a new game, he would even get admonished by my grandmother when he went overboard.

In his new job, very quickly, my grandfather became a trusted friend and confidante for the children of Shri Rao’s family. He realised that any complaints about their behaviour made to Shri Rao resulted in strict punishments, which he could not bear to watch. He decided to use his own methods to get the best outcomes. First, he drew up a timetable for them right from 5:30 AM to 10 PM whereby academic studies were balanced with physical exercise, playtime and imbibing of Dharma. The household already had strict discipline – in the evenings, a grand aarti was performed every single day in the special temple within the premises of the Rao residence, which no one was allowed to miss. The patriarch of the family liked to see his flock together.

Sometimes the children chafed under the discipline and revolted. One afternoon, GKT discovered to his panic that the children had vanished to see a movie without anyone’s permission. He rushed to the theatre where the movie was running and got an announcement made to ask the children to step out immediately. When they exited unwillingly, he promised to take them to see the same movie if they cooperated and went home on time for the evening aarti in which their absence would surely invite punishment. True to his word, my grandfather took the children to see the same movie later after getting permission from their elders.

The children were adept swimmers and often went to swim at a public swimming pool. One day when they were behaving rather boisterously at the pool, after all requests fell on deaf ears, my grandfather jumped right into the pool, swam up to them and firmly dragged out each one of them. They were shocked out of their wits because they had no idea that GKT was an excellent swimmer too. It gave rise to a new respect for him.

Slowly and surely, by becoming a part of their fun and play, my grandfather drew the children into a higher world of learning and thinking. He strongly believed that teaching through play was the best way so he frequently joined them in games. This was unusual at a time when it was the norm for parents and teachers to be extremely strict and formal with children. In the mornings, the children were taught to chant Suprabhatam and Gajendra Moksha. Everyday, GKT taught the children some new shlokas or Dharma Sutras. When his students engaged in debates, he would not rest until relevant reference books had been searched and produced to make a point. The famous English poems and plays were also not left behind. When GKT taught Kalidasa or Shakespeare, he modulated his voice to suit the characters and even acted out some parts, which the children loved. He kept a watch on their progress in school and college and made sure they passed in flying colours. Most importantly, he helped them to shun laziness, value excellence and develop a healthy respect for ancient Indian traditions such as Sandhyavandana by explaining their meanings and contexts.

As the children grew up, took leadership roles in myriad businesses, and got married one by one, GKT continued to shuttle between Bengaluru and Madras while working in the publishing division. He edited journals such as Dharmaprakash and wrote articles on a variety of topics.

“He left an indelible impression on our minds both as teacher and as a friend,” said Late Shri K. Balakrishna Rao, eldest scion of Shri Rao’s family in an obituary to my grandfather written in Dharmaprakash journal in 1977. “Whatever I am today, I am because of Shri GKT,” said Shri Ramvittal Das, another son of Shri Rao, who is proprietor of many hotels including Paradise Hotel in Mysore, when I interviewed him recently. “He had the biggest impact on my life; he was a complete man and even today when I offer tarpana in the morning, I include him and your grandmother,” he revealed. “Sometimes, when I am complimented for a good presentation or speech delivered to bank managers and government officials, I realise…everything I say comes from him,” he added.

Smt K.V. Geetha Rao, his sibling – also a business leader in the hospitality industry – echoes his thoughts. “He was simply remarkable – a guru par excellence, and he taught us to constantly take inspiration from ancient wisdom while moving forward on new avenues,” she said.

“GKT believed in our Dharma and our culture, but he would happily adopt aspects from western culture if he felt that it suited the current time,” said Shri Raghupati Rao, another student from Shri Rao’s family during the centenary celebration of my grandfather held in National College in 1994.

Many students of GKT said that he helped them to develop self-control, spiritual strength and confidence. “You and only you can control your mind,” he would tell them. “Don’t blame others – take charge of your life.” He encouraged everyone to jot down their ideas as they came to mind and instructed that notepads should be kept in every room of their houses.

In 1971 my grandfather suffered a paralysing stroke. He lost his ability to speak and could only walk very slowly. For years, the children of Shri Rao waited in vain for their beloved “meshtroo” (master) to recover and come back to work. They gave a pension to my grandmother and kept checking on his health.

My only recollection of my grandfather is his sad smile when I asked him why he could not speak. I sat on his lap and innocently urged him to repeat A, B, C, D after me. The man who wrote a thesaurus had been rendered wordless but how could I know?

Helpless though he was, my grandfather strove to be cheerful. He would stand with a ready smile if anyone suggested an outing. He let his grandchildren jump all over him right till the end came in 1977. Streams of students visited him in hospital, and his eyes lighted up at the sight of them.

Today, when modern Indians struggle to understand their Itihaasa and Shaastras without an adequate knowledge of Sanskrit, Kannada or any other mother tongue; when they have not taken control of their minds or lifestyles, the void left by gurus such as G.K. Timmanacharya becomes painfully significant.

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness,suitability,or validity of any information in this article.

Sahana Singh writes on environmental (water) issues, current affairs and Indian history. She is a member of Indian History Awareness and Research (IHAR), and has recently authored “The Educational Heritage of Ancient India – How An Ecosystem of Learning Was Laid to Waste”.