I would like to share my individual and personal views on Ambedkar, a path breaker and rebel iconoclast I have tremendous regard for. This said, he perhaps needs to be also viewed through a prism that has been sidestepped in contemporary India.

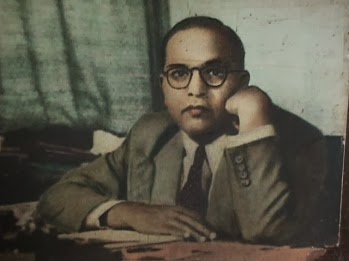

Bhimrao Ambedkar achieved a lot despite the disadvantage of birth. He rose through grit, academic achievement and politics. A complex personality, he remained the perennial outsider. The “untouchable” Mahar caste to which be belonged was a martial community that served under the Maratha empire and the British. Maharashtra demonstrated the spirit of intellectual defiance and social activism from the days of the medieval Hindu saints Namdev, Eknath and Tukaram to the reformer Jyotibha Phule in the 1800s. Ambedkar inherited that Maharastrian mantle to rebel and not conform.

A renaissance man, he had a superb grasp of economics, law and politics. He was perhaps the first “untouchable caste” graduate from the University of Bombay in 1912 where he read Political Science. He obtained a Ph.D. in Economics from Columbia University in New York, a school I had incidentally studied at, and a second Ph.D. in Economics from the University of London. He was briefly enrolled at the London School of Economics and the University of Bonn. He qualified as a Barrister in England. He joined the civil service in Baroda. Ambedkar also headed the Government Law College in Bombay.

As a state legislator, he pushed for the abolition of agricultural serfdom, defended the right of workers to strike and advocated birth control. He founded schools and a newspaper. He agitated for social reform. Ambedkar chaired the panel of eminent jurists that collectively drafted India’s constitution. He attacked Jawaharlal Nehru for purportedly lacking resolve and foresight with regards to Tibet and Kashmir. While I dispute his legacy in certain respects, Ambedkar’s commitment to the welfare of India’s Dalits can never be disputed. He serves as a remarkable role model for millions of Dalits to this day.

In my personal view, Ambedkar had shortcomings as well, often glossed over in the Indian media and academia. He joined the Defence Advisory Committee of the colonial administration in 1941 and undermined his nationalist credentials. He was an active member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council from 1942 to 1946. These were the years of the anti-colonial Quit India Movement. Blatantly pro-British, he dismissed the Indian freedom movement as a “dishonest agitation” and a “sham struggle”. He failed to enter the Lok Sabha in 1952 and in 1953. He had to be nominated to the Rajya Sabha instead. His theories on Indian history and religion were far fetched and unsupported by evidence. Towards the end, he became a bitter man.

Ambedkar’s demand for caste-based electorates neatly fitted in with the colonial divide and rule policy. The British approved separate electorates for the “depressed castes” under the “communal award scheme” of 1932. Mohandas K. Gandhi’s fast unto death campaign forced the colonial authorities to revoke the policy. The proposal would have further institutionalized caste divisions in the political arena had it been implemented. The objective after all is to jettison caste, not reinforce it.

A desperate Ambedkar converted to Buddhism in a dramatic fashion just seven weeks before he died! Malcolm X in the United States rejected Christianity for similar reasons and adopted Islam in order to provide dignity to the African-American. Ambedkar was harsh in his assessment of Hinduism. Many traditional Buddhists do not consider his radical interpretation of their religion to be in keeping with the teachings of the Buddha. He rejected the central Buddhist concepts of Samsara and rebirth. Indian neo-Buddhists view him as a Bodhisattva. On Islam he made these comments in 1946:

“No words can adequately express the great and many evils of polygamy and concubinage, and especially as a source of misery to a Muslim woman. Take the caste system. Everybody infers that Islam must be free from slavery and caste. […] [While slavery existed], much of its support was derived from Islam and Islamic countries. While the prescriptions by the Prophet regarding the just and humane treatment of slaves contained in the Koran are praiseworthy, there is nothing whatever in Islam that lends support to the abolition of this curse. But if slavery has gone, caste among Musalmans has remained”.

I would contrast Ambedkar and Malcolm X with the Rev. Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela. The actions of Ambedkar and Malcolm X did not lead to inner reconciliation and healing. Theirs was an angry rhetoric. Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela, on the other hand, reached out to the oppressor. In so doing, they reaffirmed a profound and universal humanism that healed the injustices of the past. Mandela had been jailed for 27 years in contrast to Ambedkar who was never imprisoned. The British in fact had made Ambedkar a cabinet minister. Both King and Mandela attributed their political inspiration to Mohandas K. Gandhi.

That said, Ambedkar remained an outstanding lawyer, politician, economist and educationalist. He reminds us of our shared guilt as Hindus i.e. the injustice of “untouchability”. The Dalit agenda of dignity, respect and equal opportunity needs to be addressed once and for all not just in India but in the Sri Lankan North in order to heal the scars on our collective psyche.

I would recommend two books for the interested:

(i) Koenraad Elst, “Indigenous Indians: Agastya to Ambedkar,” New Delhi: Voice of India, 1993

(ii) Arun Shourie, “Worshipping False Gods: Ambedkar, and the facts which have been erased”, New Delhi: Harper Collins, 1998.

I tend to disagree with Shourie’s harsh assessment on Ambedkar though he provides useful information glossed over by the Indian media. Elst presents Ambedkar in a positive light while he simultaneously dismisses the contemporary Dalit re-rendering of Ambedkar’s legacy.

(This was first published in the Sri Lanka Guardian. Republished with permission.)

‘Dr. Naresha Duraiswamy is a Sri Lankan national. He received his doctorate in International Relations at Columbia University. His writes on Hindu civilization and public life with a focus on law, economics, statecraft and sociology.