Every story can be dated not just by the year of its publication but by the vintage and identity of its characters and the events described in the narrative. Now, in a time when we mark everything digitally, both ideas and products become dated rather quickly and get morphed to meet one’s fancy and confuse us about the who, when, and where. The question therefore is: is it imperative that we only review books that have just been published? In the age of excess and distraction, the shelf-life of books is short. Does it therefore make sense reviewing a book published a decade ago when there are so many new books to be read? It may indeed seem idiosyncratic or whimsical to read and review a novel published a decade ago. But a review reprise is in order for those books that did not or could not find their sturdy legs when first published, or those that did not run up the bestsellers list as they should have, and despite some good reviews did not go “viral”. It is on those grounds, and with that motive here is a review of a book that offers us “a light of this world” – a story that offers us keen insights into a milieu and a people, and a life and a world past that is deftly and skillfully narrated.

This is the story of Parashuram. Replace Parashurama, the sixth avatar of Vishnu, the Brahmin-warrior carrying the axe, with Parashuram, the anti-hero: a lonely, bereft boy, abandoned by his parents, and taken care of by his Gandhian grandfather – actually, the elder brother of his grandfather, and thus Big Grandfather, pedda thaatha — Sundara Rama Krishna garu. Simple in dress and manners, honest to the core, steeped in Indian lore and morning puja, Big Grandfather is also the “pitamaha” the granddaddy of Telugu cinema – maker of classic Telugu films that swayed the Andhra masses with heroic tales of Rama and Krishna, and before those epics documentaries that stoked the nationalist passions of a colonized people. Parashuram, in the care of his grandfather, is well taken care of but teased, mocked and led by the nose by his cousins, called Pashudham, Pashu even, a little lonely cur whose dreams of starring as the youthful Krishna in one of his grandfather’s films comes crashing down when clever manipulators lead his unsuspecting grandfather up a Hyderabad garden path.

A summary of a plot cannot do justice to a story well told, nor can such summaries showcase the masterstrokes of a skillful artist. Take this beginning of Chapter 2: “It was around twenty-five years ago that I was taken to Big Grandfather’s house to live. It was halfway between Tirupathi and Madras, between the Lord and Industry as it were, most appropriate for a mythological movie-maker’s house,” or, raising a lump in your throat, the smells and sights of the India of the 1970s: “All I remember of parents are the backs of their heads, and the smell of Brylcreem from my father’s head,” or, “As we left the airport, Seenu… handed me a toy aeroplane, and it was called a Caravelle. It was a severance gift from my parents….” The Caravelle is nostalgia, a reminder of a time lost, for those of us who lived and grew up in the ‘60s and ‘70s India. Yes, the Caravelle was retired only in 2005, but history buffs would know that it was first inducted into the Indian Airlines in 1964 but the Caravelle now is a reminder of the loss of a young boy at the airport in Madras.

Vamsee’s clear eye for details, and his keen ear for the lilt of Telugu and the cadences of English give us a peep into the lives of Andhra/Telugu people and places that makes it a rare novel of its kind: something that others have noted and have thus urged Vamsee to create an Andhra oeuvre like that of R. K. Narayan’s “Malgudi” stories. Big Grandfather is saintly, loving, benign and beloved: “But he was a worldly man too. Sometimes, he carried a fifty rupee note that would show through his shirt pocket….” Big grandfather’s house was a bustling place, with him holding court, helping people, planning new movies, and with cooks, caretakers, car drivers catering to the many who lived in and visited the house it is a refuge for many. It was the time everyone knew that Big Grandfather was the one who had made SLM the megastar that he had become, and had roped in “Baby Devi” to star in his films. SLM cannot be mistaken for anyone but the famous Telugu megastar and politician NTR (NT Rama Rao), and Baby Devi cannot be anyone but Sri Devi, another Telugu contribution to the world of Indian films and Page-4 gossip and passion. Interesting verisimilitude!

But Parashuram’s dreams of playing Krishna splinters, and so begins Pashu’s nightmare journey in a boarding school with dreams of becoming a writer. Boarding school, classes, teachers who punished children with the too common and too many “Stand up on the bench,” or “Kneel down,” or “Show me your knuckles,” bruising routines makes Parashuram wonder at his fate, and worry about what he is really good at. Not much, he decides, but except for writing and dreaming, and observing, like the time when one of Big Grandfather’s movie was shown outside on the school campus, and the cooks and the servants and the school staff came to watch, eagerly, after their evening dinner, “with the smell of their food on their hands”. Twelve years of school, and he knows only that he can write, often desultorily, and sometimes helping classmates with their letters and their essays, and nothing more. Finding the book, “Word Power,” he declares to pump himself up: Parashuram, Primal, Primaeval, Primordial poet!

Skipping college, and waiting for inspiration and a break in fate he finds himself on a surrealistic journey into political campaigning for Baby Kumari, a cousin, that takes him into the hinterland of Andhra, into the longing lives of the poor, and the noisy, tiring, dusty, dirty aspects of political make-believe, and then strangely, as fate would have it, into the surreal world of AK, a woman so energetic, and scheming, and plotting, and making things happen that Parashu gets pulled along in her wake, going where she determines he should go, doing what she believes he can, and therefore ending up in America, first as a graduate student, and then as a “fixer” for AK’s many needy young people – from students to artistes to IT workers to those seeking a hand in matrimony. Vamsee’s acutely sharp observations on small American university towns (in one of which he did his own graduate work), of the loneliness of Indian graduate students, especially those pursuing the humanities, and of the varieties of Telugu people who have, in droves, made America home, and many who have prospered despite their shaky command of the English language make for both hilarious and poignant reading.

The Primordial Poet ends up in San Francisco (where Vamsee now teaches at the University of San Francisco), and we enter a “film noir” phase in the narrative that is imaginative, troubling, discombobulating. From Parashuram’s yearning for a mate, to his managing a matrimonial website for AK, and to his frightened response to the events of 9/11 we are taken on an American rollercoaster ride whose twists and turns both dazzle us and make us giddy but also make us desperate for a quick, clean, safe arrival/landing. But before we arrive, there is a pause, a “Book Two” with eight chapters, that gets us flying with hummingbirds into Parashu’s dreamworld, myth universe, nightmare spare time – bound with the fables from Greece – taking us into the world of Perseus and Medusa – and the tipping point for the present – where we can quickly tumble into a technological dystopia or recover our sanity to recreate a garden on earth. Some readers may find this “Book 2” a flight of fancy, to pun, but the haunting images that Parashuram creates of a world in trouble, and his longing for a woman to fall in love with, and his yearning to find and return home makes for some of the best reading in this memorable novel. Without giving away the ending, we can say that with “The Mythologist” Vamsee Juluri has given Andhra/Telangana a home and a flag in the Indian world of English fiction, and with Parashuram he has created a protagonist who is warmly endearing. Parashuram’s life must be pursued further, and it is for Vamsee Juluri, ten years later, to take up that gauntlet and take us on another journey into Parashuram’s world of myth, make-believe, and the very, very real uneasy world we live in. Vamsee Juluri’s love of and comfort with Hindu Gods and myth, his ease with the nuances of Indian philosophy, a rare attribute in most writers of English fiction in India, is another reason why he has to revive Parashuram. In the past decade Vamsee has written important books (“Rearming Hinduism,” 2015), endearing myth (“Saraswathi’s Intelligence,” 2016), and scholarly tomes (“Bollywood Nation,” 2013), but readers of The Mythologist would yearn for Parashuram’s further forays in this troubled world.

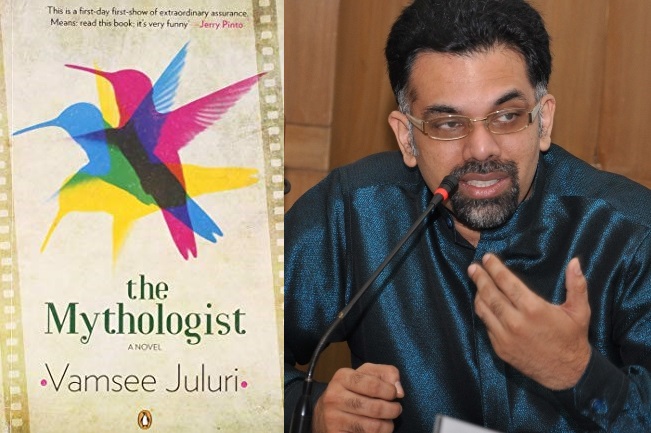

Featured Image: Amazon, Swarajya

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

The author is Professor of Communication Studies, Department of Communication, Columbus State University, Columbus, GA. He has published widely over the past three decades, and his latest book is titled, “The Election that Shaped Gujarat & Narendra Modi’s Rise to National Stardom”.