“If anthropocentricity with respect to ecological problems is the problem – envisioning the universe as a dharmic system, in which we are instigated to be unselfish, is the answer”. – Professor Vishwa Adluri

“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.

And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

And God said, Behold, I have given you every herb bearing seed, which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in the which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat.” – Genesis 1:27 – 1:29

So, if Man has been given dominion over the Earth, all its resources and all the creatures living in it, then what does it say about the Man given the status the Earth is in, today? And what does it say about the omniscient who would give dominion to such irresponsible creatures who are so bent on burning down the same house they live in? Or is it that Man himself invented such a God that would impart a sense of morality and freedom to Man to do as he pleases, without any regard for consequences and responsibility?

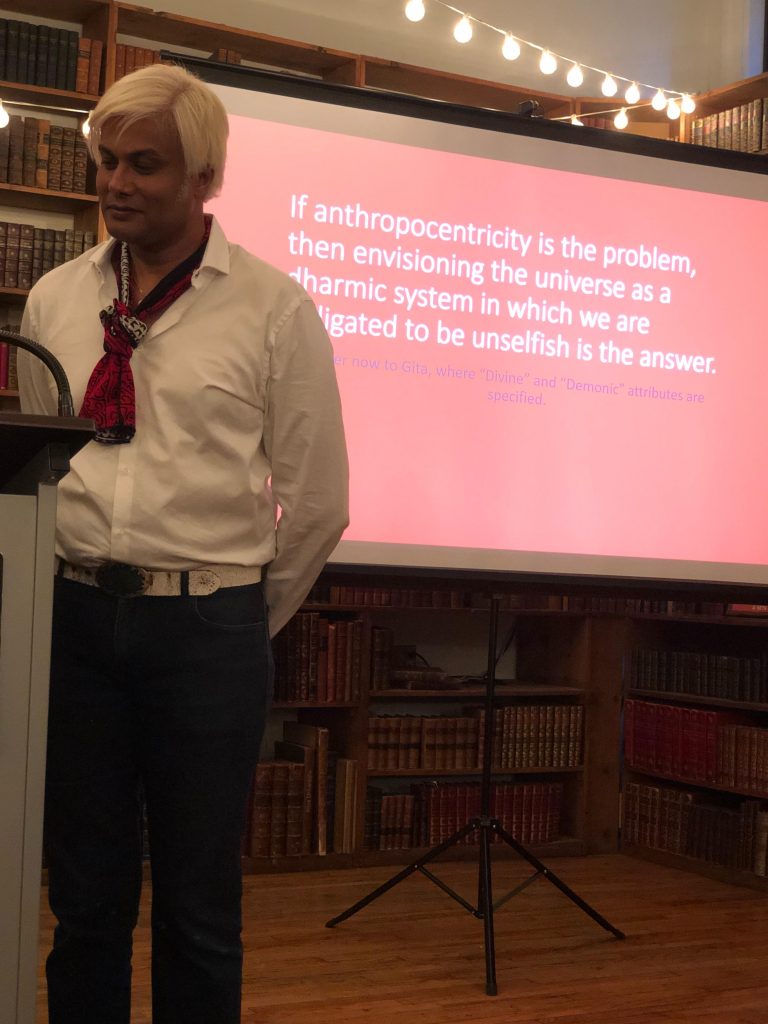

These and many more thought-provoking questions were asked in a recent talk titled ‘Unburdening the earth – Hinduism and Modern Ecology’ by Prof. Vishwa Adluri, Professor of philosophy, religion and art history at Hunter College in New York, who is a well-known scholar on the Mahabharata. He is also the author of the acclaimed book ‘The Nay Science: A History of German Indology’, which has been widely praised as “the most devastating critique of Indology and the historical-critical method till date.” In this regard, he has given many lectures in which he details how the Mahabharata, despite its hoariness, has solutions to a large number of current problems whose impact transcend cultural and national boundaries.

In this talk organized by Think Olio at the famous Strand Bookstore in New York City, Prof Adluri presents an exploration of philosophy in the Mahabharata and how it can be applied to solving the present-day ecological crisis. He began with describing the axioms that underlie the western conceptual framework. This, he explains, would help one identify the pitfalls when we speak of ecological issues and would also help us frame the problem better by avoiding the trap of modernism, that is, dehumanization of the issue.

In this talk organized by Think Olio at the famous Strand Bookstore in New York City, Prof Adluri presents an exploration of philosophy in the Mahabharata and how it can be applied to solving the present-day ecological crisis. He began with describing the axioms that underlie the western conceptual framework. This, he explains, would help one identify the pitfalls when we speak of ecological issues and would also help us frame the problem better by avoiding the trap of modernism, that is, dehumanization of the issue.

Prof Adluri laid out the 3 crucial questions concerning ‘man’ (as in ‘mankind’):

Design – What is nature vs reality? Is the Universe a material thing? What’s man’s place in it? Are we the only intelligent species, and is it up to us to save the world?

Destiny – What is man’s destiny qua man? What is it we are here for? What’s our destiny? What should we talk about – is man steward of the earth?

Disaster – Are we headed towards disaster in the future?

Given these questions, Prof Adluri proceeded to explore historical roots of the present ecological crisis. He explains the first phase was the centralization of Christian theology in understanding who man was. According to Christian belief, man was the chosen centre of God’s attention and everything else in the universe exists only to serve his needs. Over a century ago, man who was fancied himself as the centre of all creation & the rest of creation as mere service providers to satisfy his needs, invented technology to giving him powers that he never previously possessed. This meeting of Christian theology and science exacerbated the environmental crisis. It is important to note that though we might imagine that we currently are free of the dogma of Christian theology, it is evident that our present-day relationship with technology and the environment is heavily influenced by it.

Prof Adluri traces the roots of current Modernism to old Christian theology. It is no surprise therefore, that both have a linear conception of time and while ‘Old’ theology considers god having given man dominion over the entire earth, modernism assumes man as the only rational creature and all of nature to be his supply of resources. While ‘old’ theology states man’s destiny is that of a future influenced by god, modernism posits that man’s future would be influenced by technology. Curiously (or rather not!), both the ‘old’ and ‘new’ visions agree that man’s ultimate destination to be that of ‘Utopia’. Interestingly, both these ideologies concur that man is destined to face catastrophe in the future, however, while the ‘old’ theology states that man would probably be able to stave off catastrophe by redeeming himself in the faith of God (make mankind great again!), the new ‘modern’ vision contends that man would be able to stave off catastrophe by simply developing technological remedies.

It’s in the uncanny similarities of these two ideologies, that Prof Adluri contends, that modern technology furnishes proof of the anthropocentricity of theology. Here, modern mastery of technology is a means to an end – technology continues to see nature as a resource to be exploited and utilized. This separates humans from nature, and echoes an old argument that early Christians in Europe had made against the pagans – that they are ‘stupid’ to worship nature. This had caused banishment of all of pagan thought into irrationality, sentimentality & femininity. Several centuries later, in our present world, the will to master technology becomes all the more urgent, the more technology threatens to slip from our control. We have now arrived at a point where technology dictates our lives more than ever. Most of our jobs just intend to keep the machinery going. In fact, it makes one wonder whether technology is driving us or we are driving technology, since we are nothing but data, to the technology that dominates our lives, such as Social Media, for instance.

Prof Adluri refers to German philosopher Martin Heidegger who contends that modern technology doesn’t bring forth a poiesis – we do not think of our modern technology certain kind of ‘coming forth’. We instead see technology just as a process of fulfilling our demands – ‘what can I do in order to get this?’. This entraps us so that we put forth complex and unreasonable demands from nature – ‘I want to eat every crop every time, I want to eat tomatoes in January!’ This reduces all of creation to mere supplies of energy extracted and/or stored. We now look at nature and ecosystems as mere mineral deposits and sources of energy. The thinking has become so entrenched that man now sees everything, even which is concealed from him, as a mere reserve to be used & exploited. He is willing do anything, as long as a payment is involved. In the end, man exalts himself as Lord of the earth, here Prof Adluri uses the Sanskrit term Mahipati, giving rise to one fatal delusion – wherever he looks or goes, man encounters just man and his interests. The entire universe has nothing of value except man, his will and his interests. Hence, Prof Adluri concludes that, modernity is, nothing but a new chapter written in the book of Abrahamic theology and states that if one were to continue, mankind’s progress would careen out of control and crash land. Unless, we apply the brakes first, then take time to examine the thinking that led us to this present state of affairs.

Prof Adluri then prescribes 5 principles of the transition process – to help overcome the delusions such as ‘What is new is better’, “What is Modern is superior to what was before”, “Modernity means linear, chronological progress”:

- Moving Forward to the Ancients – Carry ourselves from the brashness of modernity to the time-honoured wisdom of the ancients.

- Moving away from the Christian conception of reality to a more wholesome one.

- Moving from anthropocentricity to cosmology – to reflect our understanding that man is but a speck in the universe.

- Moving from historicity to poetry – the narrative of history is almost tyrannical because there is just one story, one truth. Hence, we should move to poiesis where our thought process is more self-conscious.

- From desire to have power over everything to the mastery of the self.

Prof Adluri explains that this transition has already been attempted before in the history of western thought as is evident from the works of European philosophers Heidegger, Nietzche and Focault.

Why the Mahabharata? You may wonder. Prof Adluri quotes Mahabharata 1.1.37-38 – ‘just as signs of seasonal change are witnessed during the beginning of each season, there exist beings which are seen in beginning of each eon’. The quote further states that the wheel of existence rolls on, causing creation and destruction, regardless of anything, beginning-less and endless. The most important point to take away from this, according to Prof, is that in this vision of reality where the observer is not the centre, anthropocentricity is impossible.

Prof Adluri further explains that the Mahabharata contains in itself the iconography of Hinduism’s plastic and performing arts. He adds that because its self-consciously poetic (i.e. everyone knows they are making poetry), it is automatically epistemic, that is its self-conscious of itself as an image of a cycle gone by. Therefore, the Mahabharata is not merely a record of material happenings but a complete text that embodies the cosmic guiding principle, Dharma, due to which Hinduism is also known as Sanatan Dharma (Eternal Dharma).

Thus, the Mahabharata’s importance as a guiding text in solving the ecological crisis Man finds himself in, can be gleamed by understanding the following 5 transitions:

- Wisdom of the Ancients – The Mahabharata is itself an hour-glass shaped culmination of the Vedic tradition, with everything following out of it forming the basis of contemporary Hinduism.

- Functioning Model – It has the attraction of being a thriving, functioning model as Hinduism is the world’s third largest religion. Importantly, contemporary Hinduism enjoys a far more continuous relationship with its ancient philosophy compared to that between European Christian and Pagan models.

- Anthropocentrism to Cosmology – according to the Mahabharata and more particularly the Bhagavad Gita, cause of all reality is brahman which is an absolute. The entire universe emanates from this first principle and dissolves back into it. Man is just one entity in this ‘matrix’ like universe.

- Historicity to Poetry – Time is cyclical. Thus, no history is ever absolute. No future is redemptive. Christian theology considers salvation as the remedy for damnation and since Hinduism since don’t believe in damnation, one needn’t believe in salvation and history as a salvation myth. This implies the universe is a giant reality game with the player (aatman) trying to escape from this giant repetitive loop. This thinking makes the profound leap from dumb materialism into poetry. And Mahabharata is explicitly designed as one gigantic loop.

- Control to Mastery – human beings are different from animals, in that they can chose knowledge over their present desires. Because the universe is considered a giant virtual reality, they can choose ‘knowledge’ as the only goal and means of escape from the illusion. ‘Knowledge’ here means a direct perception of the absolute, eternal and self-illumined basis of reality. Such knowledge is occluded to us by our desires which turn us outwards.

The organizing principle according to the Mahabharata is Dharma, Prof Adluri explains, which is divided into numerous categories such as natural law, political law, social law, personal law, rules for ethical conduct etc. Hence, every human being is born into an ethical matrix – one enters this universe to do one’s duty just as sun emerges in the sky to do its job of shining. In this one cannot speak of rights as the properties attached to one as man made in the image of god. There is however, the language of obligation – how ought one be esteemed and respected if one does his or her duty to the society and universe properly. The Mahabharata thus tells one, how best to do her Dharma – and live for benefit of the world. One is also taught to transcend the world through knowledge. Therefore, the follower is thought to neither despise nature or seek to be master of it. Importantly, Adharma – unethical behaviour is prohibited strictly, and is defined as behaviour that is destructive to self, society and nature. The Bhagavad Gita goes a step further and categorizes all egotistic behaviour as adharmic, that is, it states that egotism is demonic, while living according to dharma is divine. To further buttress his point here, Prof. Adluri, quotes extensively from the 16th chapter of the Bhagavad Gita, where Sri Krishna expounds to Arjuna the characteristics of divine versus demonic behaviour. See Appendix.

According to the Mahabharata, the universe is an emanation of brahman where man is no different from the from rest of creation. This implies that he has no special essence, no special status, compared to rest of creation and the Earth doesn’t depend on man, nor is it for man’s use. Man, however, can use his special faculty – the knowledge that Dharma can free him from the bondage of the giant repetitive loop of time to free himself, if he so chooses. This according to Prof Adluri is the most important lesson that one can learn from the Mahabharata.

Prof Adluri then buttresses his point by showcasing examples of iconography in ancient & medieval Hindu temples inspired by the Mahabharata. Here, brahman is represented is represented in the form of a sleeping Vishnu, from whom the entire universe emanates. The huge snake Adisesha whom Vishnu sleeps on is time itself, The snake is coiled upon itself, representing the cyclicity of time. Indeed, in the beginning of the Mahabharata, while Vishnu is fast asleep when Bhoodevi (Mother Earth) comes to him and complains that she can no longer bear mankind, as they become a burden upon herself. Vishnu then promises her that he will manifest in the earthly realm as an avatara and cause an epic battle, resulting in the unburdening of the earth. This, Prof Adluri explains, is an example that the Hindus thought that the role of divinity lies in unburdening the Earth and not in offering mere individual salvation.

Therefore, Prof Adluri concludes that,

“If anthropocentricity with respect to ecological problems is the problem – envisioning the universe as a dharmic system, in which we are instigated to be unselfish, is the answer”.

Hence, while from the perspective of individual pleasure, the universe exists as an anthropocentric construct, but when we shift perspective to thoughtfulness, it’s revealed as a grand cosmic dance.

Appendix

Olio Presentation: 22 June 2018 – Vishwa Adluri

- 1: Lynn White

White, Lynn Jr., “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis.” Science, New Series, Vol. 155, No.3767 (Mar. 10, 1967), pp. 1203-1207

[A] Especially in its Western form, Christianity is the most anthropocentric religion the world has seen. As early as the 2nd century both Tertullian and Saint Irenaeus of Lyons were insisting that when God shaped Adam he was foreshadowing the image of the incarnate Christ, the Second Adam. Man shares, in great measure, God’s transcendence of nature. Christianity, in absolute contrast to ancient paganism and Asia’s religions (except, perhaps Zoroastrianism), not only established a dualism of man and nature but also insisted that it is God’s will that man exploit nature for his proper ends.

[B] At the level of the common people this worked out in an interesting way. In Antiquity every tree, every spring, every stream, every hill had its own genius loci, its guardian spirit. These spirits were accessible to men, but were very unlike men; centaurs, fauns and mermaids show their ambivalence. Before one cut a tree, mined a mountain, or dammed a brook, it was important to placate the spirit in charge of that particular situation, and to keep it placated. By destroying pagan animism, Christianity made it possible to exploit nature in a mood of indifference to the feelings of natural objects. The victory of Christianity over paganism was the greatest psychic revolution in the history of our culture. It has become fashionable today to say that, for better or worse, we live in the “the post-Christian age.” Certainly, the forms our thinking and language have largely ceased to be Christian, but to my eye the substance often remains amazingly akin to that of the past. Our daily habits of action, for example, are dominated by an implicit faith in perpetual progress which was unknown either to Greco-Roman antiquity or to the Orient. It is rooted in, and is indefensible apart from, Judeo-Christian teleology. The fact that Communists share it merely helps to show what can be demon-strated on many other grounds: that Marxism, like Islam, is a Judeo-Christian heresy. We continue today to live, as we have lived for about 1700 years, very largely in a context of Christian axioms.

[C] I personally doubt that disastrous ecologic backlash can be avoided simply by applying our problems more science and more technology. Our science and technology have grown out of Christian attitudes towards man’s relation to nature which are almost universally held not only by Christian and neo-Christians but also by those who fondly regard themselves as post-Christians. Despite Copernicus, all the cosmos rotates around our little globe. Despite Darwin, we are not, in our hearts, part of the natural process. We are superior to nature, contemptuous of it, willing to use it for our slightest whim. The present Governor of California, like myself a churchman but less troubled than I, spoke for the Christian tradition when he said (as is alleged), “when you’ve seen one redwood tree, you’ve seen them all”. To a Christian a tree can be no more than a physical fact. The whole concept of the sacred grove is alien to Christianity and to the ethos of the West. For nearly 2 millennia Christian missionaries have been chopping down sacred groves, which are idolatrous because they assume sprit in nature.

- 2: Martin Heidegger

Heidegger, Martin. “The Question Concerning Technology.” The Question Concerning Technology, and Other Essays, tr. William Levin, pp. 3-35, New York, 1977.

- “Modern technology too is a means to an end.” “We will master it. The will to mastery becomes all the more urgent the more technology threatens to slip from human control.” (pg 5)

- “What is modern Technology? It too is revealing. Only when we allow our attention to rest on this fundamental characteristic does that which is new in modern technology show itself to us.

And yet the revealing that holds sway throughout modern technology does not unfold into a bringing-forth in sense of poiesis. The revealing that rules in modern technology is a challenging [Herausfordern], which puts to nature the unreasonable demand that it supply energy that can be extracted and stored as such. […]. The earth now reveals itself as a coal mining district, the soil as a mineral deposit.” (pg 14)

- “The unconcealment of the unconcealed has already come to pass whenever it calls man forth into the modes of revealing allotted to him. When man, in his way, from within unconcealment reveals that which presences, he merely responds to the call of unconcealment even when he contradicts it. Thus, when man, investigating, observing, ensnares nature as an area of his own conceiving, he has already been claimed by a way of revealing that challenges him to approach nature as an object of research, until even the object disappears into the objectlessness of standing-reserve” (pg 19).

- The essence of modern technology is Enframing, according to Heidegger. “the way in which the real reveals itself as a standing-reserve.” (pg 23)

- “as soon as what is unconcealed no longer concerns man even as object, but does so, rather, exclusively as standing-reserve”.

[Man] comes to the point where he himself will have to be taken as standing-reserve. Meanwhile man… exalts himself to the posture of lord of the earth.

This illusion gives rise in turn to one final delusion: It seems as though man everywhere and always encounters only himself.” (Pg 26-27)

- 3: Bhagavad Gita in the Mahabharata. Van Buitenen Tr. (modified)

Krishna said: For whenever the Law languishes, Bharata, and lawlessness flourishes, I project myself. I take on existence from eon to eon, for the rescue of the good and the destruction of the evil, in order to re-establish the Law. (2.4, 5)

Chapter 16, On Divine and Demonic Qualities

Krishna said: Fearlessness, inner purity, fortitude in the yoking of knowledge, liberality, self-control, sacrifice, Vedic study, austerity, uprightness, non-injuriousness, truthfulness, peaceableness, relinquishment, serenity, loyalty, compassion for creatures, lack of greed, gentleness, modesty, reliability, vigour, patience, fortitude, purity, friendliness, and lack of too much pride comprises the divine complement of virtues to him who is born to it. Deceit, pride, too much self-esteem, irascibility, harshness, and ignorance are of him who is born to the demonic complement. The divine complement leads to release, the demonic to bondage. […]

There are two kinds of creation in this world, the divine and the demonic. I have spoken of the divine in detail, now hear from me about the demonic.

Demonic people do not know when to initiate action and when to desist from it; theirs is neither purity, nor deportment, nor truthfulness. They maintain that this world has no true reality, or foundation, or divinity, and is not produced by the interdependence of causes. By what then? By mere desire. Embracing this view, these lost souls of desire, which is insatiable, they about, filled with the intoxication of vanity and self-pride, accepting false doctrines in their folly and following polluting life-rules. Subject to worries without measure that end only with their death, they are totally immersed in the indulgence of desires, convinced that that is all there is. Strangled with hundreds of nooses of expectation, giving in to desire and anger, they seek to accumulate wealthy by wrongful means in order to indulge their desire.

“This I got today, that craving I still have to satisfy. This much I have as of now, but I’ll get more riches. I have already killed that enemy, others I still have to kill. I am a master, I enjoy, I am successful, strong, and happy. I am a rich man of high family; who can equal me? I shall sacrifice, I shall make donations, I shall enjoy myself,” so they think in the folly of their ignorance. Confused by too many concerns, covered by a net of delusions, addicted to the pleasures of desire, they fall into foul hell. Puffed up by their egos, arrogant, dunk with wealth and pride, they offer up sacrifices in name only, without proper injunction, out of sheer vanity.

Embracing egotism, overbearing strength, pride, desire and anger, they hate and berate me in their own bodies and in those of others. Those hateful, cruel, vile and polluted men I hurl ceaselessly into demonic wombs. Reduced demonic wombs birth after birth, and deluded, they fail to reach me, and go to the lowest road. The gateway to hell that dooms the soul is threefold: desire, anger, greed – so rid yourself of these three. The man who is freed from these three gates to darkness, and practices what is best for himself, goes the highest road. He who throws away the precepts of teachings and lives to indulge his desires does not attain to success, nor to happiness or the ultimate goal. Let therefore the teaches be your yardstick in establishing what is your task and what is not, and, with the knowledge of what the dictates of the teaching prescribe, pray do your acts in this world.

Watch the full here.

Featured Image: YouTube