Apparently it has become become utterly “regressive”, “backward”, and “reactionary” to be proud of narrating a version of history from the Hindu perspective – the perspective of the side which lost the battle. The history just referred to here relates to events that transpired in 1303 AD (Chandra 2007) in Chittor, located in the south-eastern parts of modern-day Rajasthan. Chittor happened to be the second most powerful princely state of the time after Ranthambhor, according to the historical accounts of “medieval India” written by the celebrated leftist historian Satish Chnadra. The same historian notes that the jauhar ceremony, which is central to the controversies irked by champions of feminism like Devdutt Pattnaik in his latest series of tweets on the ongoing Padmavati row, was for the first time recorded in Persian by Alauddin Khalji’s court poet Amir Khusrau. This is an important observation, because by this statement the historian has drawn our attention to the distinction of a ritualistic ceremony being described by oral sources and the same being described by a written source.

Anyway, coming back to the controversy kindled by Pattnaik, the first thing we note is that Pattnaik is a self-proclaimed “mythologist”. Going by the books he has penned and the TV shows where he frequently appears, one understands that what he really refers to as “mythology” is a well-defined category in the Hindu culture – itihāsa-purāṇa. The strategy involved in appropriating the itihāsa-purāṇa genre is a time-tested one, and it consists in erasure of the indigenous point of view in favour of the invader/coloniser’s cultural standpoint, thus legitimising the narrative of the invader/coloniser. It effectively reduces the worldview, philosophy, understanding and centuries of lived experiences of the indigenous to a child’s fantasies and story-mongering wherein the child’s accounts of ‘what things are’ or ‘how things happen’ are condescendingly looked upon by an adult. In short, this approach, invented by the British in their colonising enterprises undertaken in various parts of the world: in the Americas, in the African continent and in the Indian Subcontinent, is equivalent to the infantilising attitudes taken by the world of the adult. Thanks to the father of Marxism, we have a very precise summary of this attitude or approach: “they cannot represent themselves; they must be represented” (Marx 2005). Although Marx made this statement in the context of the French peasantry and the possibility of they forming a coherent class in economic and political terms in order to represent their “class interest” in the face of a “hostile opposition”, the aforementioned condescending attitude of the orientalist and the colonialist shines through Marx’s statement as he considers the French agriculturists to be nothing more than a collection of economic units bereft of a sense of and desire for nationhood. This is comparable to the approach of the British colonialist historians like V.A. Smith, who in their loyalty to the British Empire and its “civilising” mission in the colonies of Asia and Africa repeatedly represented the colonies as infantile, fragmented and prone to despotism. Another leftist historian R.S. Sharma observes that “the Western scholars stressed that Indians had experienced neither a sense of nationhood nor any form of self-government” while discussing the case of the colonialist, pro-British imperialist history of India (Sharma 2005). Like Marx’s ignoring of the sense of community of the French peasantry as well as their reverence for and faith in a French nation under the leadership of Napoleon, Smith too dismisses the pre-colonial Indian sense of nationhood, cultural unity and geographical mapping of territories. Sharma notes: “India was represented as a land of despotism which had not experienced political unity until the establishment of the British rule…British interpretations of Indian history served to denigrate the Indian character and achievements, and justify colonial rule.” (Sharma 2005)

Thus, in ignoring how the Indian tradition itself has categorised some of its important literary and historical genres, Pattnaik displays his complicity in the Western exercises of orientalising, dubbed by Edward W. Said as Orientalism in the following terms: “there is in addition the hegemony of European ideas about the Orient, themselves reiterating European superiority over Oriental backwardness, usually overriding the possibility that a more independent, or more sceptical, thinker might have had different views on the matter.” (Said 2001) The Indian category of itihāsa-purāṇa, as opposed to the Western, Hellenic-origin genre of ‘mythology’ (the Greek ‘mythos’ denotes legend/myth; while ‘logos’ denotes speech/spoken word), is such an example of independent thinking, if not a sceptical one; a different way of systematising knowledge of the lived, embodied Indian experience; and certainly a more sophisticated understanding history and conception of time than what the Western academia had made of mythology and the discipline of history till as late as late twentieth century. It is only very recently that the Western academia has started to take oral accounts, memory and storytelling practices of the indigenous as serious sources of preserving and acquiring historical knowledge. But these epistemological advancements have already been achieved by traditional Indian knowledge systems way before the birth of Christ! What is more, the ancient Indians had been able to refine these modes of preserving knowledge and turned them into marvellous devices of recording memory so that they can not only be recalled easily, but reproduced and performed in the exact same manner as they used to be millennia ago. Case in point: the surviving śākhā-s of the Vedas.

The sleight of hand played by Pattnaik and other postmodernists is as follows: replace the very issue of erasing one version of history in favour of the other one that rejects it, trumps it, deletes it – giving the matter, a feminist deconstructivist twist. According to this reading, Jauhar is a ‘patriarchal’ custom which “denigrates” women as it encourages them to resort to honour killing (by committing suicide) instead of braving the trials of a rape survivor’s life. Outrageous as it may sound, Pattnaik’s musings fail to attract any serious engagement with them as they completely de-contextualise the events from the mores and ethical framework within which the concerned community (Rajputs) functioned at the time when the events took place. Surely the codes of chivalry and honour have faced a paradigm change between that time and our time, but it will be irrational to expect that people, and especially the people of the Rajput community (as well as people from the Hindu community in general) – who have the highest stake in this battle for historical narrative – would judge the course of action that Rani Padmavati and her fellow royal women adopted from the (evolved) ethical framework of our times. The Rajputana of Rani Padmavati and Rana Ratan Singh is not today’s State of Rajasthan, their time is also far removed from ours. But oral history, as much as written history, maintains a bridge between that chronotope (time and space) and this chronotope. History serves exactly that purpose through the device of narrative. Therefore, the key to controlling history lies in the narrative – and the Hindu-Rajput narrative over Rani Padmavati’s history is seriously jeopardised by what the upcoming Sanjay Leela Bhansali promises to depict, as well as by the deconstruction -cum- (wishful) reconstruction that Pattnaik et al are trying to spin around it. This is even more disagreeable for the reason that such a deconstructive reading tends to portray Alauddin Khalji’s regime only as a benign, benevolent, unifying, properly administered and welfare state-like entity. That may appear true only from the perspective of ideologues and zealots who harbour the ambition of establishing a worldwide theocracy under the flag of a single religious symbol someday; otherwise his reign would be remembered as a time of chaos, religious persecution, desecration, destruction, genocide, destitution, despondency and trauma – which is how the Hindus, Jains and Buddhists remember Khalji’s reign, and legitimately so.

The problem with such one-sided narratives is that these totally ignore and thus erase the immense destruction and violence caused to non-Muslims out of human memory. Such erasure has been seen as a sort of violence – ‘epistemological violence’ to be precise – by the French Jesuit scholar Michel de Certeau. (Highmore 2006) Epistemological, because such approaches cause great harm to one or more means of acquiring knowledge, and as a result cause certain forms of knowledge – often indigenous – to go into oblivion. Orality has come to be recognised as a potent source of historical knowledge, scholars in the academia are increasingly concentrating on oral resources such as oral epics, lores, legends, folk songs and that trend is nowhere more apparent than in the corridors of the Western academia. No doubt such trends have arisen in the postcolonial era as the decolonising process gained momentum after the Second World War, and as more and more students and scholars from erstwhile colonies started to flock the universities in their former colonisers’ land in the West. Starting from Africa and the East European countries, oral traditions and various oral sources came to be recognised as valid sources of historical knowledge. Thus we got pioneer works in the field by Ruth H. Finnegan (1977), Walter J. Ong (1982), John Miles Foley (2012), again Finnegan (2012) and many more.

The present author had the chance to enrol himself in a course in oral history offered by a prominent Italian oral historian named Alessandro Portelli in late 2016, which was jointly organised by Government of India’s Global Initiative for Academic Networks (GIAN) and Jadavpur University. During that course, Professor Portelli, who teaches at the University of Rome – La Sapienza, emphasised with illustrations from his own research on American history and its oral sources that carefully listening to the various accounts of members of a community (whose history concerns the historian) is central to eliciting historical information – so carefully that even minute changes in the register of the orator’s/speaker’s voice may give rarely available insights into the events of the past and its impact on the members of the community. Professor Portelli informed the class that he has lived and worked among the working classes of Italian and American towns for a long period, and he was quite frank in confessing his sympathy for the cause of the labour unions and local leftist political parties in both countries. So clearly leftist intellectuals and academics are recognising oral accounts and reception of historical events by the community whose history they wish to narrate and construct (academically). In this, they have shifted their stance from the Marxian obsession with ‘scientific objectivity’ to ‘subjectivity of a community experience’. This appears to be consistent with the changes brought into leftist politics and scholarship by the Frankfurt School and postmodernism, which helped the New Left keep its original Marxian worldview of hostile binaries intact even after the classical Marxist binary associated with class struggle became invalid with growing irrelevance of the economic stereotypes created by Marx. Instead of bourgeois vs proletariat, humanity came to be seen as consisting of group binaries such as men vs women, hetero- vs homosexuals, white vs black, Christian vs Muslim etc. The basic Marxian structure of oppressor vs oppressed thus survived in the new binaries relevant in the new world.

However, the question remains, why ignore one community’s orality (in this case, of Rajputs and Hindus in general) while recognising that of others? Is that because their narrative is in direct contradiction with the narrative of the left’s predetermined “oppressed class”, so much so that the roles of oppressor-oppressed get reversed in this case? Because India is still a country where Hindus are in majority, the left and its intellectual framework will rather treat their narrative of being oppressed at the hand of the invader Khalji as invalid, falsified, or worse – made up with an eye for the next electoral calculations? Isn’t the left and its intellectual class playing an essentially electoral game, according to its own set rules, in order to secure its usual minority vote-bank? Isn’t the leftist academic giving up on her academic commitment and integrity (assuming, for the sake of the argument, they cared for such things) in appeasing one group and shunning another by denying their legitimate right to narrate its own history from its own experiential perspective? For one group of oppressed, the leftist academics and public intellectuals have “mindful listening” in offer, while for another, they condescendingly deny the bare minimum – a hearing, a chance to narrate the community’s own experience, its own historical narrative. What remains of that history – which is denied the scope to be narrated by the community that had to bear its brunt first-hand – other than a bunch of fictitious accounts made up by postmodernist artists, filmmakers, myth-makers and ‘critiques’?

While signing off this article, the author came across a remark, made by a friend on a social media platform already inflamed by heated discussions over the same topic, which seemed to precisely summarise the double standards in applying today’s ethical and social norms on events of the past, and events that reaches us through legends, storytelling, songs and such other sources of oral history. The remark brought Rani Padmavati’s ethical code of honour and that of Sansa Stark – a fictional character from the popular TV series Game of Thrones – under comparison. The remark read: “ironically, the same people cheer when Sansa in GoT says “if we lose tomorrow, I’m not going back there alive”.” This observation lingered on, kept hanging in the air, constantly raising questions and highlighting the hypocrisy of Devdutt Pattnaik’s wilfully interpreted, deconstructive myth-making exercises.

Works Cited

Chandra, Satish. History of Medieval India. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan , 2007.

Highmore, Ben. Michel de Certeau: Analysing Culture. London: Continuum, 2006.

Marx, Karl. Karl Marx: The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. New York: Mondial, 2005.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient. New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2001.

Sharma, R.S. India’s Ancient Past. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2005.

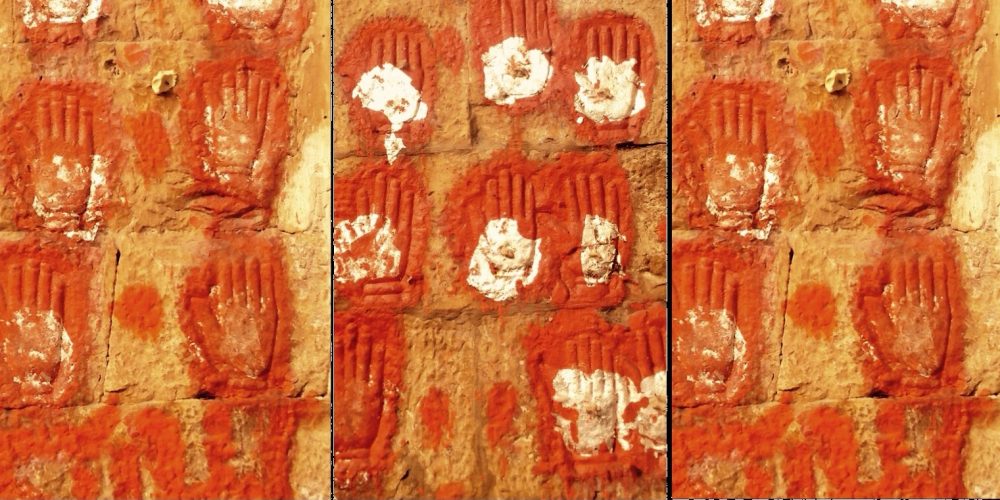

Featured Image: www.thedawntraders.wordpress.com

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Sreejit Datta teaches English and Cultural Studies at the Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham in Mysore. Variously trained in comparative literature, Hindustani music and statistics; Sreejit is an acclaimed vocalist who has been regularly performing across multiple Indian and non-Indian genres in India and abroad. He can be reached at [email protected]

Blogs: https://medium.com/@SreejitDatta | http://chadpur.blogspot.in/