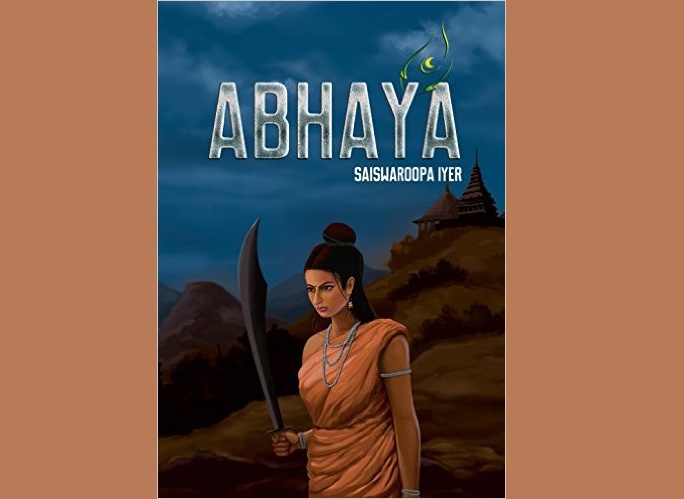

“Our home isn’t just Anagha,” the wise and fearless Abhaya says in Saiswaroopa’s thrilling debut, “our home is everywhere that civilization stands by dharma.”

Abhaya has seen enough already to be wise, though she is but a young princess, slightly unsure of things as she is thrust into great inter-kingdom rivalries and intrigues, and slightly unsure too about the feelings in her heart for that kind, mysterious, and cool friend next door in the city of Dwaraka. Homes have been ravaged, kings betrayed and slain, wolves and raptors feast in the ruins of once happy towns, and yet, somehow, those who remain must fight for what is right, for civilization, and for dharma.

I haven’t enjoyed a story as much as Abhaya in a very long time. From the breathless excitement of a chase and rescue in the first chapter involving a woman, her lover, and a violent mob intent on what the modern world calls “honor killings,” we are taken on a journey across the lives and minds of one of the most interesting cast of characters assembled for a tale about ancient India. Abhaya, and a skillfully understated Krishna, are of course the heroes, who hold our hearts, and the future of sanity, in their hands; but there are brothers and sisters, mothers, tyrants, hypocrites, liars, and most of all the powerful figure of a woman revered as the Goddess herself, seeking to liberate the poor, mistreated women of the plains from their oppressors, but might not herself be aware of the dark fundamentalist conspiracy being hatched by a pseudo-religious zealot for domination and destruction.

Fundamentalism, patriarchy, governance, ethics, and of course, love, are all well-considered themes in Abhaya, even as a fast-paced adventure unfolds. Saiswaroopa follows in the path explored in the Shiva Trilogy by Amish in terms of weaving in several contemporary concerns and comparisons to modern India into the tale, but also brings in her knowledge of classical Telugu literary traditions to play in stimulating ways. As my own knowledge of this literature is limited, I found her introductory essays useful in appreciating the rich cultural world that has produced this work, while at a more experiential level, I could completely find myself transported into the sort of world of brave and intelligent women we grew up with in Chandamama and the great NTR epics of the 1950s.

Years from now, when academia opens up enough to take Indian writing and popular culture seriously on their own terms, Abhaya will surely be studied as one of the finest examples in the civilizational rediscovery genre (and I hope we can start using something like this term instead of the dated and inadequate “mythological”). The enormous popularity of this genre, and more importantly, the enormous dedication of talented story tellers like Saiswaroopa to this creative quest, tell us that the struggle for decolonizing India is very much underway, even if august academic bodies and institutions will take a while to catch up.

While I do not want to spoil the fun for the reader of discovering the wise parallels Saiswaroopa draws between her fictional world and present-day India, one point does merit emphasis. Abhaya clearly has its hand on the moral pulse of today’s global, digital, and indeed liberal (in the true sense) Hindus who are fighting off a double-attack on them by a nasty and mendacious media-academic culture hell-bent on misrepresenting what is really churning to life after decades and centuries of colonization by ignorance. One line, for example: “The powers of Arya dharma are consolidating,” the antagonist is told, “the fault-lines that your network of Shaktas exploited all these days might not exist in a couple of years.”

In Abhaya, the reference is to the statesmanship of Krishna, as he advises his cousins the Pandavas to help gather the support of the fragmented and petty kingdoms and unite Bharata, not for some imperialist design, but simply for sustaining dharma, “that which values life over frenzied beliefs.” There are moments in the novel when the urgency of the present day India becomes indistinguishable from the story. What is that urgency, and why do I view Saiswaroopa’s moral universe here as a truly liberal one? It is simply because Abhaya and her friends do not deny that the “fault-lines” exist. We can see that they do, in the novel, and in India today. We are divided. Women are treated very badly (and increasingly men too), and much that is horrible is happening. But the important thing is that like Abhaya, we are witnessing an awakening that somehow knows how to fight those who exploit the fault-lines for their own predations and depravities, and yet nurtures its own conscience enough to also face and fight the fault-lines.

Abhaya will inspire you to be who you are, whoever you are. Read it, and get everyone you know to read it too.

The Kindle version of the book can be downloaded from here. The print book can be purchased from Amazon here.

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Dr. Vamsee Krishna Juluri is a professor of media studies at the University of San Francisco and the author of Rearming Hinduism (www.rearming hinduism.com).