The Corporation that Changed the World: How the East India Company Shaped the Modern Multinational by Nick Robins is available on Amazon.

The first multinational corporation the world saw was also the most rapacious and corrupt, ruining the world’s most prosperous economy, beggaring a seven-thousand year old civilization along the way. In many ways, therefore, the story of the East India Company is the archetypical modern-day multinational. Orient Longman, the publisher, has this to say about the book:

“The Corporation that Changed the World is a popular history of one of the world’s most famous companies. Founded in 1600, the East India Company was the forerunner of the modern multinational. Starting life as a trader in Asian Spices, the Company ended its days running Britain’s Indian empire. In the process, it shocked its contemporaries with the scale of its violence, corruption and speculation. This is the first-ever book to expose the truth about the Company’s social record. Robins reveals a hidden story of tragedy and intrigue. War, famine, stock-market bubbles and even duels between rival executives are all to be found in this new account. For Robins, the Company’s legacy provides compelling lessons on how to ensure the accountability of today’s global business.”

The author’s argument in the books is that the East India Company had a lot in common with the corporates of today, especially with the likes of Enron and Worldcom, and that a lack of corporate-governance and weak oversight on the part of the government contributed to excesses therein. Specifically, “the drive for monopoly control, the speculative temptations of executives and investors, and the absence of automatic remedy for corporate abuse.” [page 35]

The title may seem like hyperbole, but when you consider the impact that the Company Bahadur (which was the honorific bestowed on the company by the natives of the land it ruled – that would be us Indians) had on much of the world, including India and China – mostly for the worse – and mostly with tragic consequences, hyperbole does not seem like an exaggeration. This book documents the social impact of the Company’s rule in India.

I as an Indian am not particularly inclined to be neutral towards the East India Company. I am sure there was some good that the Company did do, just as the Enrons of the world did do some good. When weighed against the costs that the East India Company extracted from India, the balance is certainly does not tilt in favor of the Company, not by a long shot.

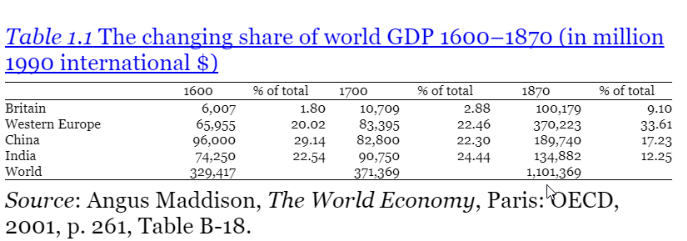

In 1700, the GDP of Britain was $10.7 billion, representing 2.88% of world GDP. The respective figures for China were $82.8B, 22.3%, and for India $90.7B, 24.4%. By 1870, these had changed to $100B (9.1%) for Britain, $189B (17.2%) for China, and $134B (12.2%) for India. [page 7]

When it comes to the soiled legacy of the East India Company, there is expectedly a marked amount of disconnect and denial that abounds in some quarters of the British aristocracy. The chief executive of the Standard Chartered Bank remarked that the challenge was now (in 2002) to “build upon the courageous, creative, and truly international legacy of the East India Company.” [page 14]. “Rod Eddington, one time chief executive of British Airways” in a similar vein saw it “as a case study in how corporations succeed ‘by dint of hard work, shrewdness and charm.’ ” [page 14, 15]. Yes, charm indeed, one wonders. The charm of the likes of Robert Clive, a petty thief, who found himself dealing with another thief, Mir Jafar, and managed to come out ahead.

The author points out, correctly, that these “romantic interpretations … fail to confront the costs associated with the Company’s business practices.” [page 15]

What contributed in no small part of the venality and the machinations of the Company employees in India was the fact that “… the Company’s overseas staff received a minimal salary and the right to conduct private trade on their own account within Asia.” [page 33]. The incentives to earn a penny or more, by hook or crook, was irresistible.

As we know, Columbus was on the search for a route to India, to trade in spices. (“… so essential was pepper as a way of making preserved meat edible… ” [page 41]) This demand was such that “In the two centuries after 1600, about one-third of the silver produce in American found its way to Asia to pay for Europe’s imports.” [page 41] That Columbus instead found his way to the Americas was another tragedy in itself – for the native American Indians.

One of the earliest and principal architects of the Company’s vision was Sir Josiah Child. “Throughout the 1680s. he was either governor (chairman) or deputy-governor” of the Company. [page 47]. “… he fervently believed profit and power must go together.” [page 48] “On 9 June 1686, Child underlined the imperative for the Company to transform itself from ‘a parcel of mere trading merchants’ into a ‘formidable martial government in India’.” [page 49]

It is often remarked by modern ‘experts’ that India cannot become a manufacturing power. The lesson these self-styles experts take great pains to point out is that China is ‘the’ place for manufacturing, and that India should be thankful for whatever advantage it has in the area of software services and diamond polishing, and leave manufacturing to the Chinese. It is therefore with some amusement that one reads that “The Indian subcontinent was then the workshop of the world, accounting for almost a quarter of global manufacturing output in 1750.” and even more so that “Even in the first century AD, the Roman historian Pliny was complaining that the extensive importing of cotton fabrics from India was draining Rome of gold.” [page 61]

Such a leadership position in manufacturing should unsurprisingly lead to the assertion in the book that “Indeed, trading houses, such as those headed by Jagat Seth and Amir Chand, were often far richer and better connected than the Company.” [page 65]

History textbooks tell us that the battles of Plassey and Buxar marked the beginning of the end of the supremacy of Indian trade, and the rise of the English loot of the subcontinent. “Plassey allowed the Company ‘to carry on the whole trade of India (China excepted) for three years, without sending out one ounce of bullion’. The reversal of global economic eminence had begun.” [page 74]

At the time, “there is compelling evidence that India’s weavers had ‘higher earnings than their British counterparts and lived lives of greater financial security.'” [page 77]. When one reads about the abject poverty that Indian artisans live and die in today, one can only weep.

Exploitation is time invariant, as the author documents. “One practice that was particularly resented was the classification of perfectly good cloth as sub-standard (ferreted). … According to William Bolt’s celebrated account, ‘various and innumerable’ were the ‘methods of oppressing the poor weavers, such as fines, imprisonments, floggings, forcing bonds on them, etc.’ … the Company’s practices led to a shocking form of self-mutilation, stating that ‘instances have been known of their cutting off their thumbs to prevent their being forced to wind silk.’ ” [pages 77, 78]

If cheating, looting, and exploitation were the defining traits of the East India Company, decadence and corruption couldn’t be far behind. Such was the extent of corruption and decadence in the lifestyles of the Company’s leaders that “A new catchphrase entered the language – ‘a lass and a lakh a day’.” [page 83]

With the interests of the Indian colony a thought absent in totality, ruination was not far behind. Food shortages and famines had been virtually unknown in India, prior to the Company’s rule. All that was one more change that the East India Company brought to India. “… Cornelius Wallard calculated that in the 120 years of British rule there had been 34 famines in India, compared with only 17 recorded famines in the entire previous two millennia.” [page 90]. Put another way, before the advent of British rule, India saw roughly a famine every 115 years, while after it was a famine every three and a half years! Even accounting for famines that may not have been recorded in the previous two thousand years, the difference is still staggering.

The famine however led to untold riches for Company officers. “One junior executive accumulated over 60,000 pounds, as rice prices soared from 120 seers per rupee at the beginning of the famine to just three seers a rupee in June 1770.” [page 91] Prices rose forty-hundred fold!

“Not only did the Company continue to collect its land revenue throughout the famine – instead of introducing some form of relief in the Mughal fashion – it actually increased the rate.” [page 92]

“In 1772, Warren Hastings estimated that perhaps 10 million Bengalis had starved to death, equating to perhaps a third of the population.” [page 92]. Mortality rates in some districts in Bengal, like Malda, reached 50%.”… in December 1770, when the Gentleman’s Magazine reported that ‘provisions were so scarce in the Company’s new acquisitions that parents brought their children to sell them for a loaf of bread.’ ” [page 95]

The East India Company did its best to suppress publication of these reports. However, it’s not as if life for the Company employees was a bed of roses. “… for the Company a round trip from London to India and back could take up to two years. … Over half its employees posted to Asia died while in service.” [page 27] Yet such was the lure of India’s riches that there was a steady stream of Englishmen making their way to India to make their fortunes. The abundance of food, coupled with a decadent lifestyle, and the hot climate of the subcontinent, proved a lethal cocktail for several of the Company Bahadur’s employees. Yet they still streamed to India, the jewel in the crown. Untold riches to be looted, untold millions to be killed.

While the book covers much more ground, I have focused this review on only a few of the aspects of the East India Company that relate to India. This is an important book that should receive wider readership than it has.

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Abhinav Agarwal is a son, husband, father, technologist and an IIM-B Gold Medalist.