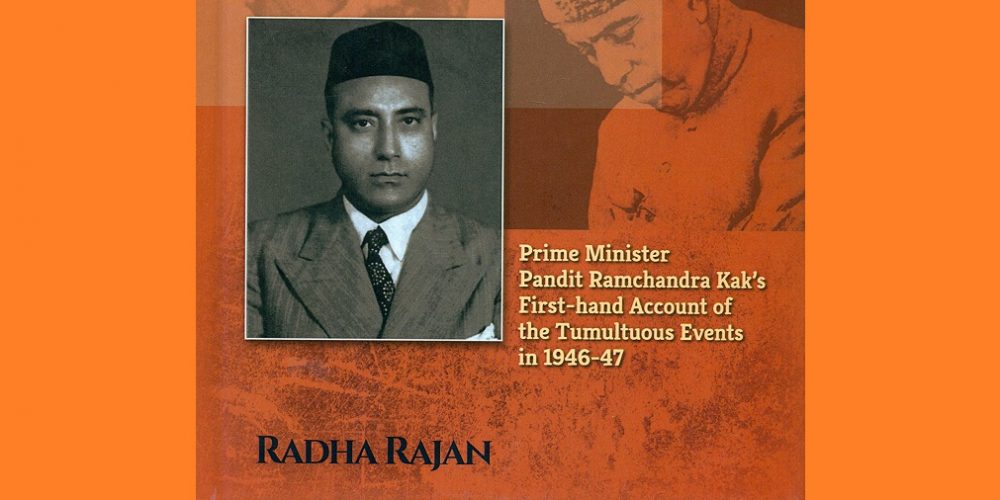

Jammu and Kashmir Dilemma of Accession: A Historical Analysis and Lesson by Radha Rajan has been published by Voice of India, New Delhi and is available on Amazon.

The mystery surrounding the delayed accession of the State of Jammu & Kashmir to India has remained shrouded in mystery for the last 70 years. The book written by the ever-vigilant Indian intellectual, Radha Rajan, has tried to clear the cobwebs of confusion surrounding the monumental event. In her seminally researched treatise, Jammu & Kashmir: Dilemma of Accession, the author has discussed the behind the scene developments relating to Jammu & Kashmir in the years immediately (preceding and) following India’s independence. Those were the tumultuous times during which India was partitioned and the Islamic nation of Pakistan was born in a welter of bloodbath. Pandit Ram Chandra Kak was the Prime Minister of the State for two years from June 30, 1945, to August 11, 1947. The question of accession of the State of Jammu and Kashmir had cropped up twice, first in 1946 when the British Cabinet Mission led by Sir Stafford Cripps visited India, and again in 1947 at the time of India’s independence. The response of Maharaja Hari Singh on both occasions was that he did not wish to accede to any country, neither to India nor Pakistan.

Interestingly the Maharaja as well as his Prime Minister, Ram Chandra Kak, both agreed that the State should not to accede to any country, though for different reasons. The reason for the refusal of Maharaja Hari Singh was the cock-eyed advice given to him by Swami Sant Dev, a priest of no consequence, who surfaced in the year 1944 and became very close to the Maharaja. He misled the ruler by prophesying that his kingdom was destined to become bigger in the near future, which made the Maharaja see the dreams of greater grandeur. In the case of Pandit Kak however, the decisive factor for refusal was the partisan attitude of the Indian National Congress to interfere in the affairs of the State and the Congress’ inclination towards handing over the charge of the State to Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah. As highlighted by the author, Pandit Kak was aware of the communal mindset of Sheikh Abdullah and was a witness to the latter starting his political career as a leader of the Muslim Conference which was a patently communal outfit. He had seen how a violent agitation was launched by the Sheikh in 1931 during which time Hindus had been harassed and targeted by mobsters belonging to the Muslim Conference. It was well known in the Kashmir valley that later on Sheikh Abdullah had changed the name of his communal organization to an allegedly ‘secular’ political outfit and called it the National Conference solely for seeking the support of the Congress party for furthering his political agenda.

The acme of the author’s intensive research is a copy of the 22 page long private note written by Pandit Kak in 1956, which reveals the behind the scene machinations of Nehru, Gandhi and other leaders of the Congress party to hand over the strategically important State to Sheikh Abdullah for using it as his political fief for self-agrrandisement to undermine the unity of India. The note gives graphic details of the violence and mayhem unleashed by the Muslim Conference presided over by Sheikh Abdullah. Among other things, the document also reveals how today’s most dangerous weapon of stone-pelting used by the jihadi goons was first invented by the Muslim Conference.

With the benefit of hindsight, it stands proved that the assessment of Pandit Kak about the duplicitous character of Sheikh Abdullah was more than correct. The bitter truth dawned on Nehru much later in the year 1953 when he was compelled to arrest and jail Sheikh Abdullah on charges of criminal conspiracy and sedition. By then substantial damage had been done to India’s attempt to reclaim the political ground, which the National Conference had captured in the Kashmir valley ironically with the full support of Gandhi, Nehru and the entire Congress leadership. In retrospect, it appears that Pandit Kak was a better strategic thinker and visionary than the Indian National Congress, which could not see through the dirty game being played by Sheikh Abdullah because of the Congress’ explicit hostility towards the Indian Princely States. This was a major failure for which the Congress party, especially Gandhi and Nehru were squarely responsible.

Serious misgivings about the future of the State again rose in the mind of Pandit Kak when Sheikh Abdullah launched the so-called ‘Quit Kashmir’ campaign in 1946 when mobs used to surround the houses of respectable members of the Hindu minority in a bid to terrorize the householders, including their womenfolk, by hurling filthy abuses and throwing stones. Ultimately Pandit Kak had to order the arrest of Sheikh Abdullah for curbing the rising tide of lawlessness, much to the chagrin of Nehru. Without realizing the ground situation, Gandhi drafted a resolution proposed to be passed by the Congress Working Committee, which castigated the State Government for arresting Sheikh and sought his immediate release. Among other things, the resolution sought to constitute a committee to probe the so-called repressive measures taken by the State government, a committee which had no legal sanction. The arrest of Sheikh Abdullah in May 1946 prompted Pandit Nehru to proceed to Srinagar despite a clear warning by Pandit Kak that the former would not be allowed to enter Srinagar. Nehru and his accomplices were stopped at the border-post of Kohala and housed in the Dak Bungalow at Uri. In response to the call of Gandhi, he returned to Delhi via Rawalpindi.

The author has exposed the nefarious role played by Lord Mountbatten by misusing his position as Governor General in the post-independence years. While fulfilling the objective of the former British rulers to deny the control of the strategic State of Jammu & Kashmir to the Indian nation, Mountbatten maneuvered to make plebiscite a pre-condition for the state’s accession to India. It was done with the approval of Pandit Nehru. Even the succour of dispatching the Indian army to save the State from Pakistani raiders was allowed only after the commitment to holding a plebiscite had been obtained from Maharaja Hari Singh.

There is an old saying that life is a harsh teacher, which gives a test first and the lesson afterwards. This eminently suited the persona of Pandit Nehru. He woke up from deep slumber only on August 8, 1953, after intelligence officers placed before him the documented evidence of Sheikh Abdullah hobnobbing with Pakistan, which included several letters and recorded tapes of his virulent anti-national speeches. The well-documented evidence shocked Nehru and he was compelled to order the arrest of his close friend and a case of sedition and criminal conspiracy was registered against Sheikh Abdullah and his 23 associates. Unfortunately, the owl of Minerva began its flight over Delhi only after darkness had enveloped the State of Jammu & Kashmir.

Among other things, in his note, Pandit Kak highlighted the fact that Lord Mountbatten had visited Kashmir in June 1947 with the specific object of getting a decision on the question of accession. When he directly asked Mountbatten as to which country the Maharaja should accede, the rigmarole reply of Mountbatten was that the final decision was to be taken by the ruler. He, however, advised that the decision should be taken after taking into account the geography of the State, composition of its population and the prevailing political situation. Prima facie, it was implicit in Mountbatten’s advice that the preferred option for accession would be Pakistan. India had to pay a heavy price for Nehru’s flawed decision to allow Mountbatten to remain as Governor General, after the partition.

The painstaking research of Radha Rajan has established two important facts of the Kashmir narrative. The first important conclusion is that Pandit Kak was a better strategic thinker than Nehru and Gandhi about the future of the State of Jammu & Kashmir. The second uncontestable conclusion is that the Congress party’s decision to retain Lord Mountbatten as Governor General was seriously flawed, even harmful to the interests of the Indian nation. Why and how Nehru opted for continuing Mountbatten as head of the Indian government has shades of white, black and grey, including the impact of the charm cast by Edwina Mountbatten on Jawaharlal Nehru and the Kashmir story. The subject requires intensive research.

This difficult to put down book will be of immense interest to all strategic thinkers and analysts. Before concluding, I would like to join in the prayer of Pandit Kak that we Indians will soon regain full control of Kashmir valley and ensure return of the displaced Hindus to their ancient homeland.

Ram Ohri is a former IPS officer and writes regularly on security issues, demographics, and occasionally, on policy.