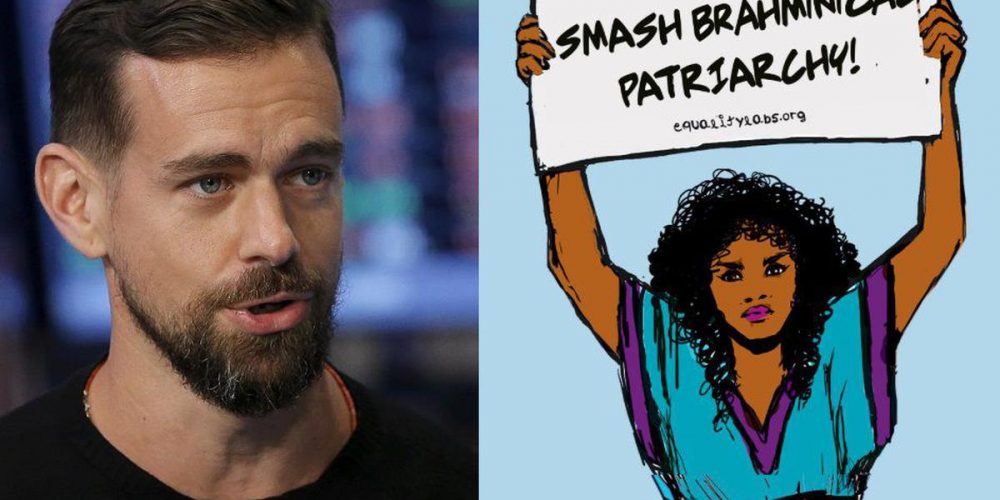

In the wake of the recent controversy surrounding the placard displayed by the Twitter CEO that mentions “Smash Brahminical Patriarchy”, one can’t wait to delve into a deeper analysis of the term, “brahminical patriarchy” which is a noun phrase with a prepositive adjective, “brahminical” followed by the noun, “patriarchy”. Thus, an attempt shall be made here to explain the meaning of the two terms as separate entities and then the meaning that the noun phrase, “brahminical patriarchy” conveys. It shall be followed by an analysis of the issue: whether such a term can actually be thought to exist accompanied by its implication in the contemporary society of ours.

What is Brahmanism?

A simple definition of the term could be as follows:

“Brahmanism, ancient Indian religious tradition that emerged from the earlier Vedic religion. In the early 1st millennium BCE, Brahmanism emphasized the rites performed by, and the status of, the Brahman, or priestly, class as well as speculation about brahman (the Absolute reality) as theorized in the Upanishads (speculative philosophical texts that are considered to be part of the Vedas, or scriptures). In contrast, the form of Hinduism that emerged after the mid-1st millennium BCE stressed devotion (bhakti) to particular deities such as Shiva and Vishnu.

During the 19th century, the first Western scholars of religion to study Brahmanism employed the term in reference to both the predominant position of the Brahmans and the importance given to brahman (the Sanskrit terms corresponding to Brahman and brahman are etymologically linked).”[1]

The above definition could be condensed to extract two essential noteworthy points:

The term, Brahman denotes two things, one lies in the realm of philosophy that corresponds to the ‘ultimate truth’ as expounded by the Upanishads, the other being in the social world that is related to a class of people in the society.

The term was invented by western scholars in the 19th century and has since then meant both philosophical as well as social Brahman simultaneously.

The intervention of the western scholars was nothing but an imperial project of Christendom to impose its faith on to all other cultures. Hence, they coined the term, Brahmanism that was synonymous with the term, Hinduism just to represent the intersectionality which they found hard to crack. Below is the kind of discomfort that the Christian missionaries experienced in their endeavour to convert:

“I believe caste division to be in many respects the chef d’ oeuvre, the happiest effort, of Hindu legislation. I am persuaded that it is simply and solely due to the distribution of people into castes that India did not lapse into a state of barbarism, and that she preserved and perfected the arts and sciences of civilization whilst most other nations of the earth remained in a state of barbarism.”[2]

Another similar narrative came from a French traveller who came to India in the 19th century. This is what he wrote:

“Is there a people in the world more tolerant than this good gentle Hindoo people, who have been so often described to us as cunning, cruel and even bloodthirsty? Compare them for an instant with the Mussulmans, or even with ourselves, in spite of our reputation for civilization and tolerance…And in what country could such a spectacle be witnessed as that which met my eyes that day in this square of Benares? There, at ten paces from all that the Hindoo holds to be most sacred in religion, between the Source of Wisdom and the idol of Siva a Protestant missionary has taken his stand beneath a tree. Mounted on a chair, he was preaching in the Hindostani language, on the Christian religion and the errors of paganism. I heard his shrill voice, issuing from the depths of a formidable shirt-collar, eject these words at the crowd, which respectfully and attentively surrounded him – “You are idolaters! That block of stone which you worship has been taken from a quarry, it is no better than the stone of my house.”

The author of this passage astonished at the level of toleration among these people (many of them might have been Brahmins) concluded with the following remarks:

…”and it is this tolerance that most disheartens the missionary one of whom said to me, “Our labours are in vain; you can never convert a man who has sufficient conviction in his own religion to listen, without moving a muscle, to all the attacks you can make against it.”[3]

Even in modern times, the attempt to tarnish the image of India’s ancient culture and practices has continued. An attempt has been made to distinguish later Hinduism from Vedic religion as mentioned in the following passage:

“It may also be added that to call this period “Vedic Hinduism” is a contradiction in terminis since Vedic religion is very different from what we generally call “Hindu religion”, – at least as much Old Hebrew religion is from medieval and modern Christian religion. However, Vedic religion is treatable as a predecessor of Hinduism.”[4]

Although to what degree is a predecessor different from its successor is often hard to decide, the point to be understood here is the attempt by western scholars to churn out narratives challenging India’s civilizational continuity.

Such half-hearted attempts to introduce new-fangled polemical ideas about India’s ancient civilization could be said to be a modern invention of the Christian missionaries who formed the bedrock of western academic project since the late 18th century. James Mill was one of the earliest to write a History of India that has since been paradigmatic to our understanding of our own past even after the abandonment of the foreign yoke. Was Mill writing a well-intentioned, unbiased history of an alien culture? An academic review of Mills’s ideas and the reasons for his criticism of the Indian society at the beginning of the 19th century was undertaken by Anna Plassart who argued:

“It suggests that James Mill’s role as a proponent of ‘utilitarian imperialism’ has been overstated, and argues that much of Mill’s criticism of Indian society arose from the continuing influence of his religious education as well as from his links with a network of Presbyterian and Evangelical thinkers.”[5]

Whatever be their hidden agenda, it is for sure that western scholars hardly understood about the culture and people publishing about which gave them wide acclaim. A brilliant caveat by Jan Gonda must be taken into account before proceeding any further:

“It is, in general, advisable in books on Hindu subjects, to utilize Christian terms only with the utmost care, and, if possible, not to use them at all to explain Indian concepts. In their well-defined dogmatic sense they do not answer to Indian ideas and in a vague and popular meaning they are unfit for scientific definitions and explanations.”[6]

Therefore, one needs to freshly investigate the meaning of the word, Brahman as could be made sense of from the classical literature of India.

What or (Who) is Brahman?

Having taken note of Gonda’s etymological grappling with fathoming the complexity of the word, Brahman, one must now turn one’s attention to the other aspect that the word denotes, that is, a class of people called Brahmans or brahmins. How does one decide upon the historical continuity and definiteness of who is a Brahmin or what constitutes the class of Brahmins. An ambiguity inescapably creeps into the discussion when one looks at what Yajnavalkya had to say in this regard. Here is what he said:

“In fact, the varnas like Brahmanas, &c, have nothing to do with birth, but with Smriti convention. Thus, NARADA, VASISTHA, VISVAMITRA and the rest are considered as Brahmanas, though their mothers were non-Brahmanas. Therefore, the rule is that the varna Brahmanahood, &c., is the creation of Smriti only, and not of any physical birth. Thus as the word ” ghata,” which originally meant an earthen jar, has now come to mean a golden vessel also.”[7]

Yajnavalkya attempted to clear all confusion by suggesting three modes in which one could be called a ‘brahman’. Balambhatta writes:

“Thus there are three kinds of Brahmanas as is said in the following verse: “Because a Brahmanahood depends either on Tapas or on Sruti, or on Yoni (birth), he who is devoid of Tapas or Sruta is merely a Brahmana by birth.”[8] The word, “tapas”, here, means “the performance of austerities like Chandrayana, &c.” Sruta means “the studying of the Vedas and the Vedangas.” “Yoni” means ” birth from a Brahmani mother begotten by a Brahmana father.” Of course a person who has neither Tapas nor Srutam is a Brahmana merely by birth and therefore not a full Brahmana.”[9]

Who then, is a “full” Brahman?

A verse from Chhandogya Upanishad brings out the difference in clearest of terms:

“Verily, there lived Svetaketu, a descendant of Aruna. His father spake unto him, “O Svetaketu, dwell as a student (with a, teacher); for, verily, dear child, no one in our family must neglect the study of the Veda and become, as it were, a Brāhmana in name only.”[10]

In order to fully engage with the subject, one needs to go through some of the accounts of Greek and Roman scholars collected and documented in the opening centuries of the first millennium after Christ going back in time till Alexander’s invasion of India’s northwest region. A brilliant example of what exactly depicted the ancient notion of who was a Brahman or how a Brahman lived could be fathomed from the dialogue between Alexander and the cave-brahmins. Greek Alexander Romance carries a vivid account of the Q&A session at the end of which Alexander was left more than convinced.

In addition to this text, Arrian’s Indika, an account of ancient India written after Megasthenes, mentions the following in the context of the Brahmins of India:

“To the philosopher alone is it permitted to be from any caste whatever, for no easy life is his, but the hardest of all.”[11]

Another philosopher of the time who was born in ancient Greece and lived in Rome had the following remarks to make:

“But, though India is actually in the enjoyment of all these blessings, there are nevertheless men called Brachmans, who, bidding adieu to the rivers and turning away from those with whom they had been thrown in contact, live apart, absorbed in philosophic contemplation, subjecting their bodies to sufferings of astonishing severity, though no one compels them, and submitting to terrible endurances. It is said, further, that they possess a remarkable fountain – that of truth – by far the best and most divine of all – and that any one who has once tasted it can never be satiated or filled with it.”[12]

The author also likes to affirm the validity of his claim in the following sentence:

“These statements are not fictions, for some of those who come from India have ere now asserted them to be facts…”[13]

If the above accounts are to be believed as well-intentioned statements issued and documented in good faith, when did Brahmanism begin to carry a negative connotation that reminds of an oppressive system based on discrimination on caste lines, overseers of which were a class of people called Brahmins? One ought to turn to other historical evidence to find out the course of Indian society.

J M Duncan Derrett observed a sharp shift in judicial administration of India in the 19th century. He wrote:

“Inscriptions give us a fair picture of what judicial administration amounted to in the 10th to early 16th centuries, and there is no reason to posit a change in the 17th or 18th except in so far as breakdown of government in western, central and northern India due to the political events of the period caused a shrinking of judicial activity, an increase in violence, and a consequent temporary lack of interest in juridical learning – which (it is most important to observe) is noticed by contemporary European writers on tour in the west and north-central India, and has been over-emphasised by historians relying upon their evidence alone. What Elphinstone and others say was no doubt true for circa 1820, but has little relevance for 1720, still less for 1620.”[14]

With regard to the sources of judicial administration, Derrett is of the opinion that the authority of the shastras was unanimously accepted. Below is what he argued:

“Non-Brahmans admitted that the Brahmans were the expounders of law, and that the Hindu religion required obedience to the dharmasastra which the Brahmans alone knew. The sastra itself, they agreed, admitted customary deviations subject to rules of its own, and in those contexts where religion was paramount the sastra was more frequently consulted than in secular matters…”[15]

A comment on the dynamics of legal administration of the period under discussion throws further light upon the ambivalence of the application of the term, Brahminical. Let us take a look:

“Where there was no correspondence the Brahmans acknowledged the force of customary law, subject the proviso that if the caste claimed any place in Hindu society certain basic propositions must be accepted-but these were not very specific, forced in any uniform way, and in fact a gradual movement of castes “upwards” towards Brahmanical standards occurred.”[16]

Thus, it must be asked as to how brahminical is our society today given the following features:

- Indian legal system is largely a mirror-image of English common law and has been completely rid of any trace of the dharmashastric

- The temples are under governmental control and are taxed which is in clear violation of ancient norms of Hinduism.[17]

- Also, the lifestyle and the priorities in our lives are largely modelled after a Judeo-Christian interpretation of the world where materialism is highly prized with almost no concern for spiritual inclination and philosophical contemplation (a defining characteristic of the Brahmins in ancient India).

Thus, it’s for us to decide whether we can call the current society brahminical. However, let us assume any such thing and try to forge a link between ‘brahminical’ and ‘patriarchy’. Thus, Brahminical patriarchy could mean either of the following:

- A patriarchy that is founded on the precepts of the Vedic scriptures, especially Upanishads;

- A patriarchy that emanates as a consequence of the class of people called Brahmins.

Hence, before proceeding further, one must find out what kind of patriarchy existed in India on account of the two.

Notes on Patriarchy

“If civilization had been left in female hands, we would still be living in grass huts.”[18]

What is patriarchy? A simple definition of the term could be:

“Patriarchy, hypothetical social system in which the father or a male elder has absolute authority over the family group; by extension, one or more men (as in a council) exert absolute authority over the community as a whole. Building on the theories of biological evolution developed by Charles Darwin, many 19th-century scholars sought to form a theory of unilinear cultural evolution. This hypothesis, now discredited, suggested that human social organization “evolved” through a series of stages: animalistic sexual promiscuity was followed by matriarchy, which was in turn followed by patriarchy.

The consensus among modern anthropologists and sociologists is that while power is often preferentially bestowed on one sex or the other, patriarchy is not the cultural universal it was once thought to be. However, some scholars continue to use the term in the general sense for descriptive, analytical, and pedagogical purposes.”[19]

Thus, Patriarchy as an academic term is of quite recent origin. It emanated from academic discourse of the 19th century when it meant “the disproportionate control of the father in families or clans”.[20] The initial focus of the term seems to have been on the ‘family’ where the father was often the head of the family. Although there were scholars like Bachofen who argued that ancient societies were based on matriarchy but, it was largely accepted in the academic field that in most societies, it was the father who headed the affairs of the family. The concept assumed new form in the twentieth century when it was extended to the whole of society and it is this definition of patriarchy which is largely responsible for igniting a gender war in today’s society, though largely in the west, but as we experience in the recent example our society is not left untouched either. The newer definition pertains to “the organization of an entire society in ways that exclude women from community positions.”[21]

Patriarchy in ancient Sanskrit literature – Or, is it?

Thus, we shall now examine the conditions of ancient society of India and check whether it corresponds to the above definition of patriarchy.

Yajnavalkya tells us that the class of girls called brahmavadinis in ancient India were educated and brought up in a manner that was identical to how the boys were raised casting doubts on the existence of patriarchy in those times.

Furthermore, Patala 1, section 2 of Apastamba Grihyasutra carries the following precept:

- All seasons are fit for marriage with the exception of the two months of the sisira season, and of the last summer month.

- All Nakshatras which are stated to be pure, (are fit for marriage);

- And all auspicious performances.

- And one should learn from women what ceremonies (are required by custom).[22]

The institution of Wifehood in ancient India

While women were considered indispensable for all august occasions and religious ceremonies, special attention ought to be paid to the status they enjoyed within the institution of Wifehood. The ancient texts in Sanskrit are replete with references to women, especially in their elevated status in the role of the wife. Vishwamitra, the ancient sage equated the wife with the “home” itself.[23] An entire hymn in the Rigveda was devoted to marital affairs which again lauds the high status enjoyed by women as the sovereign of the house. It reads:

“Become sovereign queen over your father-in-law; become sovereign queen over your mother-in-law. Become sovereign queen over your sister-in-law, sovereign queen over your brothers-in-law.” (Jamison & Brereton, 2014:1525).[24]

It was believed that in domestic affairs, the wife held a position that was akin to the position of the head with respect to the body (Atharvaveda, 10. 159. 2).[25] Adding to the notion is a verse from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad which suggests that both husband and wife were one soul at the inception of the universe which later metamorphosed into two entities.[26] By virtue of the fact it seeks to emphasize the ‘oneness’ of the husband-wife dyad. The Mahabharata mentions the fact that Brahma had given only one body to both husband and wife[27] that goes in consonance with the concept of Dampati which is synonymous with the inseparable bond that binds the married couple together.[28] In fact, Atharvaveda introduced it much before the discourse of the modern West prescribed “true love” to be the cementing sentiment within conjugal relationship.[29]

Furthermore, verses from Manusmriti contain praise for women and celebrate their exalted position as wives. Below is what is says:

“Women must be honoured and adorned by their fathers, brothers, husbands, and brothers-in-law, who desire (their own) welfare.

Where women are honoured, there the gods are pleased; but where they are not honoured, no sacred rite yields rewards.

Where the female relations live in grief, the family soon wholly perishes; but that family where they are not unhappy ever prospers.

The houses on which female relations, not being duly honoured, pronounce a curse, perish completely, as if destroyed by magic.

Hence men who seek (their own) welfare, should always honour women on holidays and festivals with (gifts of) ornaments, clothes, and (dainty) food.

In that family, where the husband is pleased with his wife and the wife with her husband, happiness will assuredly be lasting.”[30]

One needs to hold one’s breath because there’s more in Manu’s text that could be seen as a clear departure from the idea of patriarchy. While in IX. 26 Manu equates wives (Striyah) with goddesses (Sriyah), he appears to be more revolutionary in his approach when he says the following:

“If, being not given in marriage, she herself seeks a husband, she incurs no guilt, nor (does) he whom she weds.”[31]

What? Can one imagine that a girl was permitted to marry a husband of her own choice? But, Manu seems to have no problem with it.

Prescriptions for the husband

Besides the above, Sanskrit texts in ancient India could also be singled out for prescribing the duties and rules of conduct for the husband that hardly finds any parallel in the literature of the West of that era. Yajnavalkya suggests:

“Or he may act according to her desire, remembering the boon given to women. And he should be devoted to his wife alone…”[32]

Another verse from the same text that accords special privilege to woman vis-a-vis her in-laws:

“Woman is to be respected by her husband, brother, father, kindred, (Jnati), mother-in-law, father-in-law, husband’s younger brother, and the bandhus, with ornaments, clothes and food.”[33]

Complete devotion towards one’s wife has been considered a virtue as depicted in the following verse:

“A wife who is pleasing to his mind and his eyes, will bring happiness to him; let him pay no attention to the other things: such is the opinion of some.”[34]

The husband is expected to take a pledge that after taking one as bride, “her words shall be acceptable to me”.[35] The Taittiriya Samhita (VI, 1, 8, 5), in its turn, states it quite categorically that the conduct of the husband with his wife should be one of decorum and he should act only on her advice in each and every situation. Such stringent ethical prescriptions for the husband is surely an astonishing feature of any ancient text when even a trace of any such thing is not to be found in other civilizations contemporaneous to it.

Patriarchy/Misogyny in literature of other cultures

In all of literature from medieval Europe, misogyny abounds which could be as harsh as equating women with beasts.[36] Furthermore, somebody as widely acclaimed for his wisdom as Socrates also spoke of women in pejorative terms as is evident from the following statement:

“All of the pursuits of men are the pursuits of women also, but in all of them a woman is inferior to a man.”[37]

Another man of letters of ancient Occident held similar views. Pythagoras remarked:

“There is a good principle which created order, light, and man, and an evil principle which created chaos, darkness, and woman.”[38]

It seems rather appalling to contrast the elevated status of wife in ancient Sanskrit texts with the clawing misogyny reflected in the verse below:

But of all plagues, the greatest is untold;

The book-learned wife, in Greek and Latin bold;

The critic-dame, who at her table sits,

Homer and Virgil quotes, and weighs their wits,

And pities Dido’s agonizing fits.[39]

Therefore, there were both patriarchy and misogyny of higher degrees in all human societies when compared with the Indian conditions. Thus, one must look for the causes of the recent controversy in other things that have nothing to do with the dynamics of Indian society.

Bringing the Culture War home

If both ‘brahminical’ and ‘patriarchy’ turn out to be hypothetical terms as is evident from a review of ancient literature of India why at all, has the noun phrase, combining the two terms popped up at this time? The current debate is nothing but an attempt by certain quarters of vested interests to bring home the culture war from the West. The “gender war” in the west rests upon the ideas of men-haters such as Catharine MacKinnon. Some of the extreme principles of radical feminism could be:

“that all intercourse is rape, that all women should be lesbians, or that only 10 percent of the population should be allowed to be male.”[40]

Thus, what the CEO of Twitter displayed could be seen as an attempt to spark a gender war between men and women with ‘intersectionality’ playing a role in introducing the idea of caste to make it even more toxic. While we have seen above that brahminical patriarchy is a completely hypothetical construct with no factual evidence, the reason why the entire issue of patriarchy has been so widely popularised is a consequence of the ignorance of the so called intellectual class of today.

Rejection of differences between sexes

Scientific research has found that men are better at working with things whereas women are better with people.[41] While the study also suggests that the gender disparity in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) careers could be a consequence of this, the advocates of gender war can barely gulp the argument. Maybe the research is wanting in some respects, but another recent study suggests that girls are as good or better than boys in STEM fields (in terms of learning) in 2 out of every 3 countries but the gender gap in STEM careers does exist and increases with an increase in overall national gender equality. Thus, gender disparity in STEM careers might be based on attitudes towards science and not academic strength.[42]

In the light of these studies, what the vanguards of “gender feminism” must understand is that correlation is not causality. If women don’t choose to pursue a particular career, their choice must be respected. The madness seems to be beyond cure when radical feminists look to achieve exact 50-50 ratio for men and women in almost everything including things such as amount of oxygen consumed and number of RBCs produced (hypothetical conditions though, but very possibly could be made real for the sake of an argument). Heather MacDonald narrates a similar tendency that severely grips the American society. She writes:

“After harassment allegations surfaced against a publisher of the contemporary-art magazine Artforum, the Los Angeles Times published a gender tally of art museum directorships. Females hold 48 percent of them—not a promising start for a diversity crusader. There is a silver lining, however: Only three women run museums with annual budgets of more than $15 million, and they’re paid less than their male counterparts. It doesn’t matter if director salaries are commensurate with experience and credentials; sexism is assumed, and impossible to rebut.”[43]

The recent American controversies involving James Damore and Brett Kavanaugh are burning examples of the fact that the American society is set ablaze consequent to the culture war. And it is not without repercussions for our country. The kind of misplaced analogies that invokes terms such as ‘White Privilege’ and ‘Jews’ as equivalents to brahmins of India is suggestive of the fact that those perpetrating these forms of microaggression have no sense of historical comparison that would have kept them informed that the historical journey of white colonizers, the Jews and the Indian Brahmins have nothing in common whatsoever. But drawing poor analogy has actually been at the root of the problem. In the 19th century the elite of Boston were termed ‘Boston Brahmins’ when Brahmins in India had no parallels with them. Hence, looking for sense in a section of people who are hell-bent upon pouring out all venom against Indian traditions shall be a folly. All we need is to recognize the lurking menace and manufacture ways of quelling it decisively. One of the foremost things we must do is to reject all academic discourse that has been produced by evangelist-sponsored, anti-India scholars for the past two hundred years. It gets easier to fabricate such realities that seldom exist because the academic world in the West has a hidden agenda of subversion that acts against India’s indigenous tradition.

Notes

[1] https://www.britannica.com/topic/Brahmanism

[2] Abee J A Dubois, Hindu Manners, Customs and Ceremonies, 3rd ed, 1924, p. 28.

[3] Louis Rousselet, India and its Native Princes – Travels in Central India and in the Presidencies of Bombay and Bengal, 1876, p. 533.

[4] Stephanie Jamison and Michael Witzel, Vedic Hinduism, 1992, p.3.

[5] Anna Plassart in ‘James Mill’s treatment of religion and the History of British India’, 2008, History of European Ideas, 34: 526-534, p. 526.

[6] Notes on Brahman by Jan Gonda (1950), p. 3.

[7] Yajnavalkya Smriti, translated by Rai Bahadur Shrisha Chandra Vidyarnava, 1918, p. 188. The lines are taken from Balambhatta’s gloss on the Smriti.

[8] Yajnavalkya Smriti, translated by Rai Bahadur Shrisha Chandra Vidyarnava, 1918, p. 189. The lines are taken from Balambhatta’s gloss on the Smriti.

[9] Yajnavalkya Smriti, translated by Bahadur Shrisha Chandra Vidyarnava, 1918, p. 189. The lines are taken from Balambhatta’s gloss on the Smriti. Emphasis added in order to highlight the point that a Brahman merely by birth was not considered a “full” Brahman.

[10] Chhandogya Upanishad, VI, 1, 1.

[11] J W M’Crindle, Ancient India as described in Classical Literature, 1901, p. 167.

[12] J W M’Crindle, 1901, p. 176.

[13] J W M’Crindle, 1901, p. 176.

[14] J Duncan M. Derrett, ‘The Administration of Hindu Law by the British’, 1961, p. 15.

[15] J Duncan M. Derrett, ‘The Administration of Hindu Law by the British’, 1961, p. 28.

[16] J Duncan M. Derrett, ‘The Administration of Hindu Law by the British’, 1961, p. 16.

[17] J W M’Crindle tells us that the temple lands in ancient India were always free from duty, a view that was also supported by Manlu.

[18] Camille Paglia, Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson, 1990, p. 38.

[19] https://www.britannica.com/topic/patriarchy

[20] Carol L. Meyers, ‘Was Ancient Israel a Patriarchal Society?’, 2014, p. 9.

[21] Carol L. Meyers, ‘Was Ancient Israel a Patriarchal Society?’, 2014, p. 9,

[22] Verses quoted from Herman Oldenberg’s English translation, 1886.

[23] Rigveda, III, 53, 4.

[24] Rigveda, X, 85, 46. The verse has been quoted from the English translation of the Rigveda by Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton, 2014, p. 1525. Also see Atharvaveda, I, 14, 3 that assigns the status of queen to the wife.

[25] As cited in Mani Ram Sharma, 1993.

[26] Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, I, 4, 3.

[27] Anushasan Parv, 211, 46, as cited in Mani Ram Shrama, Marriage in Ancient India, 1993, p 124.

[28] Rigveda, V, 3, 2; X, 10, 5 and Atharvaveda, 12, 3, 14.

[29] Atharvaveda, 3, 30, 2. It should also be seen as a critique of the thesis that Stephanie Coontz proposed in her 2005 book, Marriage: A History. She is trying to push forth her thesis that romantic love is a modern construct of the western civilization and love marriage is a relatively recent phenomenon that is hardly two hundred years old.

[30] Manusmriti, III, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60. The verses quoted here have been taken from Patrick Olivelle’s translation published in 2005.

[31] Manusmriti, IX, 91. Olivelle’s translation.

[32] Yajnavalkyasmriti, 81.

[33] Yajnavalkyasmriti, 82.

[34] Apastamba Grihya Sutra, I, 3, 20.

[35] Atharvaveda, XIV, 1, 56.

[36] Ronald Pepin, ‘The Dire Diction of Medieval Misogyny’, 1993, Latomus, 52(3), 659-663. Pepin had mainly focused on 12th century European literature.

[37] Dialogue between Glaucon and Socrates, Book V of The Republic.

[38] As quoted in Clabaugh, G. K. (2010). A History of Male Attitudes toward Educating Women. Educational Horizons, 88(3), 164-17, p. 166.

[39] See Satires from Decimus Junius Juvenal who lived in ancient Rome (60-140 AD).

[40] Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate, 2002, p. 293.

[41] Rong Su, James Rounds, and Patrick Ian Armstrong, ‘Men and Things, Women and People: A Meta-Analysis of Sex Differences in Interests’, 2009, Psychological Bulletin, 135 (6), pp. 859-884.

[42] Gijsbert Stoet and David C. Geary, ‘The Gender-Equality Paradox in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Education’, 2018, Psychological Science, 29 (4), pp. 581-593.

[43] Heather Mac Donald, The Diversity Delusion, 2018.

Featured Image: Scroll

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness,suitability,or validity of any information in this article.

The author is a PhD Scholar at the Centre for the Study of Social Systems, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.