We Hindus

In the light of foregoing, it is incumbent upon contemporary Hindus and Hindu scholars to regain the initiative and using indigenous historiography and cognitive categories and to institute a framework to generate (in multiple volumes) a genuine and authentic history of the Hindus from an insider’s perspective. Only then can we successfully remove the wild misconceptions that non-Hindus have spawned about Hindus and Hinduism.

A Sanskrit lexicon (Śabdakalpadruma) defines Hindu to be any one who categorically rejects all that is inferior and crude (hīnam duşyati iti hinduh; hinasti doşān sa hinduh). But the Hindu does not stop at merely finding faults, flaws, or deficiencies with oneself and/or with others. Hinduism calls upon him/her to remove all the faults (doşas) and seek perfection (samsiddhi) through sādhanaand the cultivation of samskāras. The ideal of perfection may not be attained, though it ever calls forth abiding effort. Perfecting man, not perfected man, therefore, should properly be called as the telos of Hinduism. It does not demand that man/woman be perfect in order to be a Hindu. The emphasis is more on the ameliorative direction of one’s life, individually and generally. In the Bhagavadgītā (5:10) Śrī Kŗşņa explains to Arjuna that anyone who performs prescribed actions without attachment to their fruits is not touched by blemishes just like the lotus that rises above the muddy waters and remains untouched by the mud. The pure, sinless lotus flower that manages to raise itself above all murky conditions (doşas) has subsequently become a standard of comparison for anyone who aspires to rise to the ideals set by Hinduism.

The individual’s aim of perfection is the same as the group’s aim of culture—the realization of the Universal Self and the Universal Community. Perfection is to individual as culture (samskŗti) is to the group: a process of becoming as well as a state of being. The individual seeks perfecting as society seeks ‘culturing’ (see Organ 1970: 171-172). Samskŗti is derived by adding the prefix sam to the root kŗ (to do) connoting an activity which renders an aspirant fit to accomplish something worthy. The Vedas extol collective life (sambhūti) which is deemed to be enduring and lasting. The Ŗgveda advises that one should strive to become eternal by serving the people (prajāya amŗtatvam asyāma). Civilization evolves when a people or a community performs series of creative actions and processes in a united spirit (samskŗti iti eki bhūya kŗtih) leading from one’s state of nature (prakŗti) to refinement (samskŗti). Translated into English, they may be identified as five ‘F’ words = food (anna); festivals (utsava); crafts and fine arts (including films)(kāla); fiction (literary works, kathā); and finance (artha).

Hindu term of self reference for such a perfecting being is Ārya. Hinduism therefore is known from within the tradition as Ārya– or Sanātana dharma. It is useful to remember in this context that Ārya (a noble being) is an ethical term without any racial connotation.Sanskritist and Indologist Madhav Deshpande cites an ancient Jain text (Pannavasutta ca. 100 BCE), which contains a long section describing the Jain conceptions of Aryan and non-Aryan (mleccha). It classifies Aryans into two kinds: exalted Aryans (iddhipattāriya; pace Doniger’s ‘That Hindu’) and non-exalted Aryans, i.e. average Aryans (aniddhipattāriya; pace Doniger’s ‘This Hindu’). The ‘average Aryans’ in turn are classified into nine different categories: Aryan by region (kşetrārya); by birth (jātyārya); by clan (kulārya); by function (karmārya); by profession (śilpārya); by language (bhāşārya); by wisdom (jñānārya); by realization (darśanārya); by conduct (caritrārya)(see Deshpande 1993: 10). This classification implicitly recognizes that whoever Aryan is; he/she is so (or can become Aryan) by taking to appropriate profession or learning the proper language and so on (i.e. by undergoing proper samskāras). In other words, unlike Doniger’s dichotomy, the distinction drawn between an exalted and non-exalted Aryan and an Aryan and a non-Aryan is not absolute and the status of the Ārya is not by birth alone. The process of aryanization is a dynamic and interactive one.

Historically, the Hindu quest for perfection (self and communitarian) is reflected and is discernible through dharma, samskŗti,itihāsa, and paramparā or the four petals of Hinduism (Hindupadma). Since ancient times Hindus have lived in small, autonomous communities held together by a common ethical code (dharma), by memories of a recorded common past (itihāsa), and by shared historical, political, social, and cultural experiences (samskŗti). This cumulative heritage (paramparā) continued to be transmitted to succeeding generations before Hindus were overwhelmed militarily by invaders beginning in the second millennium disrupting somewhat that flow. Both ‘This Hindu’ and ‘That Hindu’ would concur with this broad, ethical, and non-sectarian ideal of Hinduism.

A comparative study of world civilizations made by foreign historians and impressions about ancient Indian society recorded by numerous foreign visitors to India indicates that society and civilization of ancient India had reached higher levels than many other world cultures of the time. One of the possible reasons for this development is that the level of sophistication had percolated to all levels of society thanks to the work of community leaders who had inculcatedsamskāras in their populace. This is why we find great saints and cultural heroes rising from each community (janajāti): from barbers, leather workers to Brahmins even though Doniger would restrict them to the ‘This Hindu’ group. Manusmŗti observes that their heroic deeds and spiritual and literary achievements are recorded in the oral tradition in songs, ballads, and stories (5: 149). Thanks to this long tradition, every community inherits subtle impressions (anuvāmśika samskāras) which are twofold: metaphysical and empirical manifesting themselves in all persons (see Manusmŗti 6: 25).

Concluding remarks

Doniger’s The Hindus forces us to rethink and represent Hindus and their history using their own cognitive categories. In the context of India, a Hindu becomes ‘This’ or ‘That’ only from a particular angle of vision. In reality, they are two strands within Hinduism, seen in a particular way. In other words, it is useful to view Hinduness not as a thing or essence but a style (or rather, a family of styles). There is one single Hindu identity but with multiple faces. Again, ‘This’ or ‘That’ can no longer be seen as static. We will begin to see that most social and cultural developments in India’s long history are reflected in each of these two attitudes. ‘This’ and ‘That Hindu’ did not remain merely passive receivers of these developments, but instead were active participants in creating the composite Hindu identity.

However Doniger may hate Brahmins (male Brahmins in particular), she is forced to acknowledge “that in the myths, there were Brahmins among the ogres, and there are references to human Brahmins whose ancestors were said to be ogres. In actual life, too, there were Shudra Brahmins, mleccha Brahmins, Chandala Brahmins, and Nishada Brahmins. Some were very close indeed to the folk sources that they incorporated into the Puranas”(p. 384). Indeed, the ‘Shudra Brahmin’ collapses the chasm between the Subaltern and the Sanskritic Hindu that Doniger has dug. The Freudian and Marxist agendas tell us to look for the subtext, the hidden transcript, the censored text. Their assumption is that a subtext may be less respectable and more self-serving; yet it may be more honest and more real than the surface text. Beneath Doniger’s chasm, therefore, one might find another layer, an admiration of India, a desire to learn from India, perhaps even a genuine desire to give India something in return for providing her a career and a livelihood.

French Indologist Louis Renou criticized Western Sanskritists, Indologists, theosophists, anthroposophists, and teachers of yoga for their piecemeal approaches to Hinduism (comparable to Doniger’s ‘toolbox approach’) and concluded, “If Hinduism ever has a future as an integral part of a broad, generally acceptable spiritual movement beyond the borders of the country that gave it birth, this future will be created only by direct reflection from genuinely Indian forms of thought and spirit conceived and expressed by Indians” (cited in Organ 1970: 90). Armed with the power of samanvaya, which facilitates a wider sense of identity, a sense of coherence in a shared global context and of inclusion in a common framework and horizon, Hindus can live up to Renou’s hope. Thanks to the heritage of samanvaya, ‘This’ and ‘That Hindu’ did not [and do not] function like an island in India or in diaspora. Each has been constituted socially and imagined culturally in relation to as well as ‘against’ its other. The reference points of the social identity of ‘This’ and ‘That Hindu’ are inclusive as well as exclusive [Doniger stresses only the latter] in their own unique ways. ‘This’ and ‘That Hindu’ have equally conformed (and contributed to) shaping each other’s ethos.

Doniger fails to realize that unlike the Muslim or Christian distinctiveness, Hindu distinctiveness (coming across as ‘This’ and ‘That’) does not rest on rituals or practices in which people are marked as different and counted in or out from each other. Hindu distinctiveness is not constituted or confirmed by clearly demarcated and symbolized boundaries. James Laidlaw puts it succinctly ‘it is a distinctive way of being indistinct’ (Laidlaw 1995: 94). Doniger herself acknowledges that, “the integrative power of Sanskrit also spills over in other domains of culture: It is no accident, she states, that India is the land that developed the technique of interweaving two colors of silk threads so that the fabric is what they call peacock’s neck, blue if you hold it one way, green another (or sometimes pink or yellow or purple), and, if you hold it right, both at once” (pp. 11-12). ‘This Hindu’ and ‘That Hindu,’ indeed, are two colors of silk threads making up the Hindu fabric. If you hold that fabric right, you see them both at once.

Concluded

References:

Adams, George C. 1993. The Structure and Meaning of Bādarāyaņa’s Brahma Sūtras: A translation and analysis of Adhyāya I). Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass.

Berling Judith A. 1980. The Syncretic Religion of Lin Chao-en. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bolle, Kees. 1984. Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty in Retrospect. Religious Studies Review, vol. 10, no 1 (Jan 1984): 20-26.

Deshpande, G.T. 1971. Indological Papers Vol 1, Nagpur: Vidarbha Samshodhan Mandal.

Deshpande, Madhav. 1993. Sanskrit and Prakrit: Sociolinguistic Issues. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass.

Doniger, Wendy. 1998. The Implied Spider: Politics and Theology in Myth. New York: Columbia University Press.

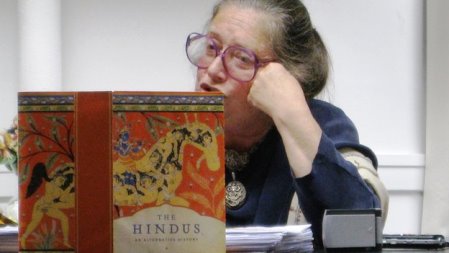

Doniger, Wendy. 2009. The Hindus: An Alternative History. New York: The Penguin Press.

Houben, Jan E.M. 1996. Sociolinguistic attitudes reflected in the work of Bhartŗhari and some later grammarians. Ideology and Status of Sanskrit: Contributions to the History of the Sanskrit Language edited by Jan E.M. Houben, 157-193, Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Laidlaw, James. 1995. Riches and Renunciation: Religion, Economy, and Society among the Jains, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lele, Jayant K. 1995. Hindutva: The Emergence of the Right. Madras: Earthworm Books.

Manu Smŗti [With the Commentary Mānavārtha Muktāvali of Kullūka]. 1946. 10th ed. Edited by Narayana Ram Acharya, Kavyatirtha. Bombay: Nirnaya Sagar Press.

Mylvaganam, Raja. 2004. Yahoo Abhinavagupta group, message # 1905 accessed on March 3, 2010.

Organ, Troy Wilson. 1970. The Hindu Quest for the Perfection of Man. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University.

Pollock, Sheldon. 1996. The Sanskrit Cosmopolis, 300-1300: Transculturation, Vernacularization, and the Question of Ideology. Ideology and Status of Sanskrit: Contributions to the History of the Sanskrit Language edited by Jan E.M. Houben, 197-247, Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Rigopoulos, Antonio. 1998. Dattātreya the Immortal Guru, Yogin, and Avatāra: A study of the Transformative and Inclusive Character of a Multi-faceted Hindu Deity. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press.

Shaw, Rosalind and Charles Stewart. 1994. Introduction: problematizing syncretism. Syncretism/Anti-Syncretism: The Politics of Religious Synthesis edited by Charles Stewart and Rosalind Shaw, London: Routledge.

Smith, Brian K. 1989. Reflections on Resemblance, Ritual, and Religion. New York: Oxford University Press.

Smith Brian K. 1994. Classifying the Universe: The Ancient Indian Varna System and the Origins of Caste. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tilak, Shrinivas. 2006. Understanding karma in light of Paul Ricoeur’s philosophical anthropology and hermeneutics. Nagpur: International Centre for Cultural Studies.

Tilak, Shrinivas. 2008. Reawakening to a secular Hindu nation: M. S. Golwalkar’s vision of a dharmasāpekşa Hindurāşţra.Charleston, SC: BookSurge Publications.

IndiaFacts Staff articles, reports and guest pieces