On June 1, the Economist “explains” as to “Why and how we make election endorsements.”

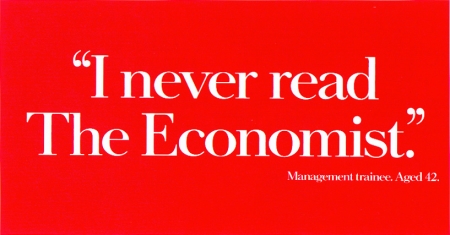

First, it is not an explanation of any sort. It is the crudest display of an arrogant and garrulous piece of journalism. The Economist’s record of reporting on India for long has been shoddy and openly biased. And extremely biased in case of Narendra Modi whose inevitable elevation it opposed in an editorial just days before Narendra Modi was declared the winner. That editorial oozing lies from almost every word, stopped short at slandering him. For some reason, the Economist has arrogated itself the right to sit in the judge’s chair and mouth all sorts of pronouncements about who India should elect and so on. In the Indian parlance, this reeks of exactly the same Nehruvian sense of entitlement that led to the Congress party’s comprehensive decimation.

The Economist hopes that Narendra Modi, India’s new prime minister, will reform his country’s economy and help his impoverished countrymen.

Even worse, it defends this sense of entitlement by claiming that “we worried that his Hindu nationalism would prove divisive and dangerous,” the innate assumption being that Hindu nationalism is itself divisive and dangerous. It’s noteworthy that the Economist has retained its unfair, ill-informed, and fraudulent view of Narendra Modi but has chosen to tread carefully now that he is Prime Minister. It seems no amount of valid criticism regarding its reporting perturbs the Economist. Consider this:

Among our Indian readers this opinion was, to say the least, controversial—not just our verdict but the fact that we advanced it at all. We ought, some readers told us, to mind our own business…

Just in case the Economist is still living in the Stone Age, these Indian readers are absolutely correct. It is one thing to play favourites–in this case, the Economist’s open bias against Modi–but it is entirely unethical to base this bias on lies and slander by still calling the communal violence in Gujarat in 2002 as a “pogrom” which he aided and abetted. And this even after the Supreme Court absolved him of any wrongdoing. And neither is this the first time the Economist has slandered Narendra Modi: a cursory look at the Economist’s archived articles about the Indian Prime Minister confirms the slander. One must give the Economist the Nobel Prize for doggedly ignoring the facts of the Gujarat riots cases over the years, and peddling its own version of the truth. Given this, turning back and castigating its “Indian readers” for daring to question the Economist’s decade-long journalistic misdemeanour in terms of having “advanced it at all” is a bit rich.

But the Economist does not stop there.

All the same, by longstanding tradition we frequently offer endorsements of our favoured candidates in important elections […] We do not think this habit is presumptuous or neo-colonial…We do not expect all of our eligible readers to follow our advice—and we aim to provide enough impartial analysis for them to make up their own minds—let alone that our opinion will sway the outcome… We fail to get our way on many issues…but we advance those views nevertheless.

What the Economist is really saying: we are the Big Brother of Journalism and we care two hoots whether you think we are fair or no. If we’re unfair, too bad. But the worse is when the Economist justifies its Big Brother-ness by claiming that “[O]ur record is not partisan.” The link to the magazine’s Narendra Modi archives are in themselves proof of exactly how partisan the Economist has been.

Neither does the Economist’s claim that it bases its endorsements on inputs from its editorial staff and correspondents wash. If that’s the case, it speaks volumes about the competence and/or integrity of its India correspondents who have supplied it with patent lies.

Just so the Economist knows, India has a vibrant media both in English and regional. While the English media is, like the Economist, heavily prejudiced against the BJP and Narendra Modi, it doesn’t make endorsements or exhort voters to vote against or for some candidate. Second, Indian voters don’t really need the Economist to tell them who to vote for and why. So yes, the Economist’s Indian readers are right in asking it to mind its own business and calling it presumptuous and neo-colonial.

And just as the Economist “hopes” that Narendra Modi will bring the economy back to track etc, Indians too hope that the Economist gets down from its high pedestal and stop playing Big Brother: butting into places and events it knows nothing about and which is none of its business.

But at the heart of the Economist’s consistent anti-Modi tirades lies exactly one word: Hinduphobia. The fear that India will at last stand on its own feet, freed from the fetters of that mental colonialism internalized by Jawaharlal Nehru and perpetuated for more than 60 years by his dynastic successors. Throughout his marathon campaign, Narendra Modi made no secret of invoking and taking pride in the cultural ethos of India–an ethos which is entirely Hindu. This among other messages found tremendous resonance with the voters. Equally, as a fitting finale, he participated in the Rudrabhishekam and the Ganga Arati in Varanasi, the constituency that put him in Parliament as Prime Minister. The Economist itself mentions this fact with trepidation. The other irritant is the fact that he speaks in Hindi unlike most former Prime Ministers who spoke in English and adopted the manners of the West when they dealt with them. It is this nativity and innate Hinduness of Narendra Modi that scares the Economist. And as his record shows, he sets the agenda and deals with people and issues on his own terms. This is why the Economist wants Modi to appease Muslims as a counter to his “appeasement for none” doctrine. Here is a leader who says he will bring about equality to all sections of the society but the learned folks at the Economist want him to grant special privileges to a few chosen sections! One wonders who is being divisive here.

And so, all the claims of the Economist that Modi “has not brought himself to mention Muslims, who make up 15% of the population,” are mere ploys to make him ashamed of his Hinduness, to play the same sickening, sixy seven year old game in the name of secularism, liberalism, and the rest. Except that it hasn’t worked with Narendra Modi because he has reversed the rules.

Sandeep Balakrishna is a columnist and author of Tipu Sultan: the Tyrant of Mysore. He has translated S.L. Bhyrappa’s “Aavarana: the Veil” from Kannada to English.