For decades, the serious practice of writing the authentic history of Indian Freedom Struggle has been going on in a selective manner where only some crusaders get the lion’s share of the honor while others are frequently disregarded. The credit for this should go to a certain sort of scholars for whom the history of Freedom Struggle starts and finishes with the role of Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. These same scholars have presented Nehru as the sole nation-builder relegating other leaders of post-colonial India to a negligible space so much so that for decades, many Indians did not even know the decisive role played by Babasaheb Ambedkar in drafting our constitution or the massive project of unifying the nation that was executed by Sardar Patel.

However post-1990 both Babasaheb Ambedkar and Sardar Patel have started to get some credit but it is still way less than what they actually deserve. The same cannot be said about the leaders and freedom fighters of pre-1947 India. The time has now come to give an accurate and complete version about the history of the Indian Freedom Struggle as well as the role played by a host of freedom fighters excluding Gandhi and Nehru.

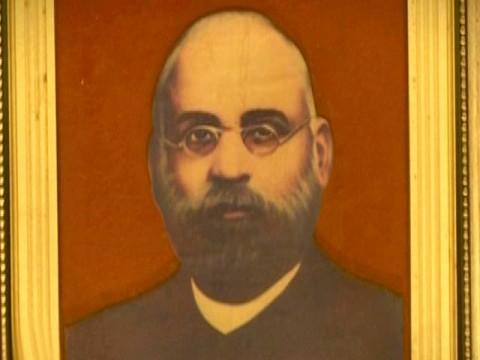

Indeed, if correct history was taught, Pandit Shyamji Krishnaverma would have been a household name by now. With about four days to go for the 67th Independence Day it is high time this praiseworthy patriot gets his correct place of honor. An outline of his illustrious life is given below.

Early Years and Education

Born at Mandvi village of Kutch District in Gujarat on the 4 October, 1857, Shyamji had his primary education in the village school at Mandvi and secondary education at Bhuj.

Around the year of 1876, he came in touch with Swami Dayananda Saraswati, the radical reformer and founder of the Arya Samaj. Swami Dayanand impressed with Shyamji’s knowledge of Sanskrit, asked him to deliver lectures on the Vedas all across the then British India. The following year, Shyamji toured nationwide propagating the values of the Vedas, which brought him admiration from many prominent scholars. His knowledge as well as his oratory skills earned him the title of Pandit from the scholars of Kashi in 1877.

His deep knowledge of the Sanskrit language also caught the attention of Monier Williams, a professor of the subject in Oxford University. Williams, impressed with Shyamji’s competence in Sanskrit offered Shyamji the post of his assistant. Shyamji accepted the post and arrived in England in 1879 and joined Balliol College on 25 April with the recommendation of professor Williams.

While there, Shyamji Krishnaverma also became the first Indian representative at the Berlin Congress of Orientalists in the year 1881. After completing his graduation in the year 1883, Shyamji Krishnaverma delivered a lecture on ‘The Origin of Writing in India’ in front of a large audience in the Royal Asiatic Society of England. Making an impact on the audience, Shyamji Krishnaverma became a non-resident member of the Royal Asiatic Society. Subsequently, he entered Temple’s Inn and was one of the first Indians to clear the Bar-at law exams.

From 1885 till 1897, Shyamji resided in India serving as an advocate in the Mumbai High Court, followed by offering his services as the Diwan of Ratlam and Junagadh State. In 1897, a deadly plague hit Pune causing the death of several Indians and the situation was worsened by the clumsy response of the British Government, causing great outrage among general public. This prompted Shyamji to immigrate to England in March 1897 with a view to launch an uncompromising campaign against the exploitative and cruel regime of the British Establishment as well as create support in England and Europe for India’s independence.

A Freedom Fighter in England

During the initial years, Shyamji would give fiery speeches in the free atmosphere of Hyde Park in London, calling for the support of progressive and sympathetic Britons in the right cause of India’s emancipation. The famed sociologist and philosopher Herbert Spencer‘s writings were his chief inspiration during those days. On Herbert Spencer’s first death anniversary on 8 December, 1904, Shyamji announced the launch of Herbert Spencer Indian fellowships of Rs. 2000 which would enable Indian graduates to pursue higher education in England. He also announced an additional fellowship in the memory of the late Swami Dayanand Saraswati.

In January 1905, Shyamji decided to put his thoughts to print by publishing the first issue of “The Indian Sociologist” – an English journal with writings about political, social and religious reform. This pragmatic monthly served a great purpose in sensitizing the progressive Britons about British misrule in India besides creating many scholarly revolutionaries in India and abroad.

Shyamji was also swift in responding to the prevalent racism that Indian students had to face in England, when he decided to bring them together under one roof very close to his own residence. The house at 65 Cromwell Avenue in Highgate, London came to be known as the India House.

This very India House produced such great revolutionaries as Virendra Chattopadhyay, Lala Hardayal, PM Bapat and Veer Savarkar. India House was formally inaugurated on 1st July 1905 by Mr. H. M. Hyndman, a leader of the Social Democratic Federation in the presence of many dignitaries such as Dadabhai Nawroji, Lala Lajpat Rai, Madam Cama, and the positivist philosopher Hugh Swinney, among others.

Though Shyamji Krishnaverma got the support of progressive Britons, the British government was incensed with his growing popularity. As a consequence, Shyamji was dismissed from the list of members of the Inner Temple in England on April 30, 1909. To avoid further harassment, he relocated to Paris in early 1907 and continued his work vigorously. The British government tried to extradite him from France but failed to do so since Shyamji was able to gain the confidence of many French as well as European politicians. He agitated for the release of Savarkar when the latter was imprisoned prompting the famous social-activist Guy Aldred to write an article in the Daily Herald under the title: “Savarker the Hindu Patriot whose sentences expire on 24th December 1960” which received a massive public response giving the British Raj a nasty headache. Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, England and France entered into an alliance making it difficult for any anti-British activists to reside in Paris.

As a result, Shyamji shifted to Geneva to continue his struggle but with some restrictions due to the pledge of political inaction he had given to Swiss government during the entire period of war. During that time Shyamji’s only support was Dr. Briess, the president of the Pro-India Committee in Geneva. However Shyamji was later shocked to discover that Dr. Briess was a paid spy of the British government. This revelation greatly frustrated Shyamji and drove him to further political isolation. But even then, Shyamji tried his best to acquire the support of the Swiss Federation and the League of Nations for India’s freedom from British rule. Unfortunately Shyamji received a bland response from both. On March 30, 1930 this great revolutionary breathed his last.

Nehru Government’s mistreatment of his legacy

Even though the British Government suppressed the news of his death, a belated tribute was paid by the valiant rebel Sardar Bhagat Singh and his co-revolutionists in Lahore Jail where they were undergoing a long-term, drawn out trial. Shyamji’s wife Bhanumati donated the whole of Shyamji’s Sanskrit and Oriental Library of to the Sorbonne University. Even today the memory of Shyamji and his wife is preserved in Sorbonne University. So deep was Pandit Shyamji Krishnaverma’s conviction on India’s eventual liberation that he made the prepaid arrangements with the local government of Geneva to preserve both his and his wife’s ashes at the cemetery and to send their urns to India whenever it became independent.

But it appeared that the Government of post-independent India did not have much belief in Shyamji’s patriotism as they never bothered to bring back his remains. Some historians believe it was because throughout his political life, Shyamji Krishnaverma always kept his distance from the Indian National Congress and never trusted it, (even though he was on amicable terms with certain Congressmen like Lajpat Rai). And so, since it was a Congress Government in power after 1947, they were repaying his incongruity in kind. Another point of view holds that because Shyamji opposed Mahatma Gandhi’s pro-British stand during the Boer War in 1899, as well as his non-violent methods, Nehru the Prime Minister and Mahatma’s pet disciple did not see it fit to honor an opponent of Mahatma. If true, both these views display petty political grudge and double standards as Nehru himself discarded many of the Mahatma’s teachings.

Interestingly, about a decade before Mahatma Gandhi entered politics, the idea of Satyagraha was promoted by Shyamji Krishnaverma as can be seen in this writing from 1905:

‘It is not necessary for Indians to resort to arms for compelling England to relinquish its hold on India… If the brown man struck work for a week, the Empire would collapse like a house of cards… If anyone refused to buy or sell any commodity, or to have any transaction with any class of people, he commits no crime known to the law. It is, therefore, plain that Indians can obtain emancipation by simply refusing to help their foreign master without incurring the evils of a violent revolution.’

But being a political realist, Shyamji accepted armed resistance as a last resort to finish the tyranny of the British Raj for which he established India House and nurtured great revolutionaries like Lala Hardayal and Veer Savarkar. True to his given designation, Pandit Shyamji Krishnaverma blended the rational views of the western scholars with the immortal wisdom enshrined in the Vedas, thus having an integrated worldview. While based in Europe, he enlightened his European hosts about the Vedas as well as Sanskrit literature. A proud Arya Samaji, he would have been labeled a ‘Hindu fundamentalist’ by today’s ‘secular’ scholars.

Even though under Indira Gandhi’s rule, a township in Kutch was named Shyamji Krishnaverma Nagar, his historical role was not disseminated to the general public. In 1998, the BJP government issued a postage stamp in his honour.

But it was the year 2003 that the then Chief Minister of Gujarat Narendra Modi carried out the promising task of bringing the ashes of Shyamaji Krishnaverma and his wife Bhanumati from Geneva. The sacred ashes were then taken in a ‘Veeranjal Yatra’ throughout the state culminating at Shyamji’s birthplace Mandvi. Instead of applauding this noble act, the country’s secular scholars decided to criticize Modi and BJP, exposing their warped view of history. Nevertheless, under CM Modi’s supervision, a memorial called Kranti Tirth dedicated to Shyamji was built and unveiled in 2010 near Mandvi.

Now it can be hoped that the new government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi would take necessary steps to propagate the life and teachings of a great nationalist upon whom I find the designation ‘Pandit’ more suitable. If talks could be initiated with authorities of both Geneva and Sorbonne University, the corpus of Shyamji’s writings can be shared and disseminated within India so the masses can become aware of the breadth and depth of his erudition and pioneering service to the nation. This would also serve two purposes:

- It would land another blow to the maligned statement that ‘Hindu Nationalists’ had no role in the ‘Freedom Struggle.’

- It would present the ‘Congress Mukt’ aspect of ‘Indian Freedom Struggle’ — that is, the non-Congress freedom fighters whose contribution in many cases was greater.

References:

- http://kskvku.digitaluniversity.ac/Content.aspx?ID=800

- http://www.countercurrents.org/comm-puniyani110903.htm