Link to the first part.

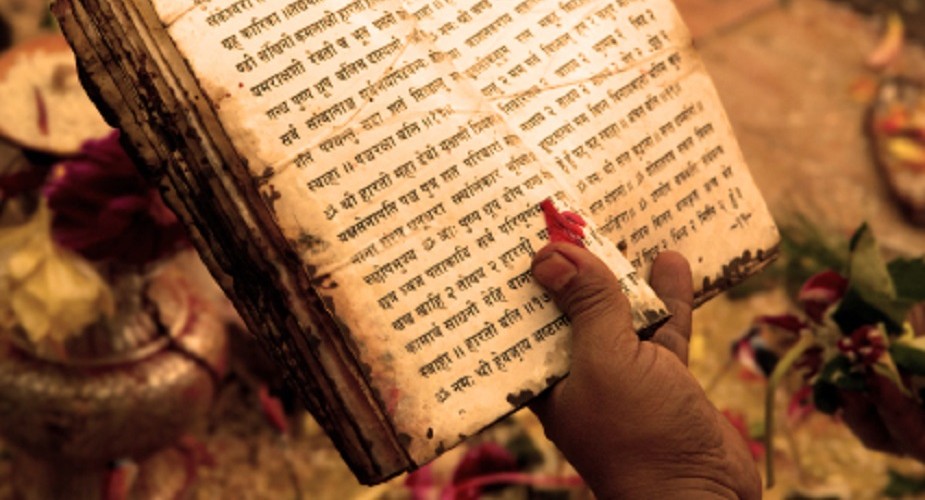

In its original and purest form, Hinduism is sanātana dharma, loosely translated as ‘eternal truth’ or ‘timeless religion’ or ‘eternal way of life’ or ‘timeless ethic.’ It is drawn from nature and thus unbounded by space-time constraints. However, in the several applications of sanātana dharma, we adopt specific spatiotemporal frames.

Sanatana Dharma

The word sanātana symbolizes eternity. From linguistic and cultural viewpoints, the word sanātana is a symbol of an unbiased, non-dogmatic, universal spirit. The word dharma does not have a proper equivalent in languages other than Sanskrit (or its derivatives). Its spirit can be loosely communicated in English with words such as ‘global ethic,’ ‘righteousness,’ ‘way of life,’ ‘culture,’ ‘principle,’ ‘law,’ ‘duty,’ etc. All these words put together signify the sustained implications of dharma. The term ‘Indian culture’ is a reasonable approximation to sanātana dharma.

Before going into the study of sanātana dharma, we shall begin a rational enquiry into values. Any faith or belief system should not be left unchallenged and we must screen it through rational enquiry and by gaining the universal experience firsthand.

Consciousness

Our perception of the world at different levels depends on us and therefore, the process of understanding depends on our mental and physical faculties. Thus our every enquiry in any field of our choice invariably presumes the self-evident existence of ourselves and proceeds from there on.

First: can we question our own existence? If yes, even such questions will be the product of our own existence. Therefore, our existence – irrespective of its kind – is eternal as far as we are concerned. Though our experiences in the wakeful state or even in the dream state are entirely different from place to place, time to time, person to person, and thought to thought, in sound sleep all of us have the same universal experience of absolute immersion and absolute detachment. Sleep is a highly refreshing and blissful state indeed.

None of the differences pertaining to natural or human-made divisions such as gender, race, age, nationality, or economic-social-cultural diversities are felt in deep sleep. Only in the states of wakefulness and dream do we have the baggage of ourselves. In the wakeful state, the sense organs and the mind are active but in the dream state, only the mind is active. Of course, it must be said here that we are speaking with a bias towards the wakeful state, because when we are inside a dream, we feel the existence of body and the overall physicality of the experience is indisputable.

None of the differences pertaining to natural or human-made divisions such as gender, race, age, nationality, or economic-social-cultural diversities are felt in deep sleep. Only in the states of wakefulness and dream do we have the baggage of ourselves. In the wakeful state, the sense organs and the mind are active but in the dream state, only the mind is active. Of course, it must be said here that we are speaking with a bias towards the wakeful state, because when we are inside a dream, we feel the existence of body and the overall physicality of the experience is indisputable.

In the state of sound sleep, neither the sense organs nor the mind are in action. However, there is no paucity of bliss. There is absolutely no inadequacy. It is a state of complete saturation. For our enquiry, we should start our analysis from this point. No study will become meaningful without a common or universal basis, such as this, to compare and contrast with any other experience. The Upanishads start their self-enquiry with this analysis.

Puruṣārthas

In deep sleep, there is no possibility for desires to arise. But in the dream and wakeful states, there is a great play of desires and dissolutions, proposals and disposals and agreements and disagreements.

Desire is the starting point of our individuality, or rather the feeling of our existence and identity. Desires drive us to action, which is essential to fulfill them. Desire stems from insufficiency, for it is the incompleteness within us that drives us to obtain something. In chemistry, unsaturated elements in terms of the number of electrons in their outermost orbit become chemically reactive and try hard to become saturated. This is the concept of valency of atoms. Similarly, our desires, according to their valencies, trigger action. According to traditional wisdom, this sequence of incompleteness leading to desire, eventually ending in activity is termed as the chain of avidya (ignorance), kāma (desire) and karma (action). Those who do not feel this incompleteness will not get caught in this downward spiral.

In the idiom of economics, desire leading to activity can be understood as demand leading to supply. In the long run, supply can never catch up with demand, for the human mind always harbours desires and demand is not constrained by materialistic limitations. This is not the case with supply. Typically, our desires get fulfilled in the material world and hence their existence is spatiotemporal in nature.

Desire, which is mental in origin and physical in manifestation, always has an upper hand over the things which try to satisfy it because the agencies which try to meet with the desire are constrained by matter, energy, space, and time. There will always be an acute shortage of supply against perpetual demand. We are aware that today we have the rapid depletion of natural resources at one end and an unlimited, ruthless world of desires eternally escalating at the other end. In sanātana dharma, the idea of demand and supply is conceived as kāma and artha. Kāma refers to desires and artha refers to the means of satisfying desire.

If desire goes on a rampage in a blind quest for gratification, the world will come to a standstill in seconds. This doesn’t happen because of the compromise – willing or unwilling – that we have made within and amongst ourselves. We agree to abide by the rules that we have ourselves set for the smooth functioning of our societies. This compromise evolves naturally, for, without it, our own existence is threatened. There is no doubt that such a compromise will not be pleasing to everyone; it is always the second-best choice in any situation (the best being what is solely convenient to us). The mode of implementation of this compromise will differ according to the frames of time, space, and mindset.

If desire goes on a rampage in a blind quest for gratification, the world will come to a standstill in seconds. This doesn’t happen because of the compromise – willing or unwilling – that we have made within and amongst ourselves. We agree to abide by the rules that we have ourselves set for the smooth functioning of our societies. This compromise evolves naturally, for, without it, our own existence is threatened. There is no doubt that such a compromise will not be pleasing to everyone; it is always the second-best choice in any situation (the best being what is solely convenient to us). The mode of implementation of this compromise will differ according to the frames of time, space, and mindset.

If this compromise is enforced from outside, it becomes a rule or an order. When it is realized from within, it becomes responsibility and awareness. Sanātana dharma calls this compromise, which is both a rule and a realization, as dharma.

These three concepts – kāma, artha, and dharma – are termed ‘trivarga’ (the group of three) and we may realize them in the physical world. The fourth concept, mokṣa (loosely translated as ‘liberation,’ ‘salvation,’ ‘release,’ etc.) is termed ‘apavarga’ (the separate group) and is treated separately from the other three since we have to annihilate desires and transcend the physical world in order to realize it. Mokṣa refers to liberation from the triangular frame of demand, supply, and compromise.

Hindu scriptures recommend, first of all, an efficient management of kāma/demand by using artha/supply by adhering strictly to dharma/compromise. This leads to a well-rounded life with its share of work and pleasure, neither losing calmness nor becoming stoic. By doing this, we will have prepared the ground for mokṣa.

These four core concepts – dharma, artha, kāma, mokṣa – are together called the puruṣārthas. In this context, the word puruṣa means ‘that which dwells in the body’ or ‘the self’ and artha refers to ‘the means’ to understand the self. This wonderful conception of puruṣārthas retains relevance across time and place and transcends gender, race, nationality, religion, and political identity.

(This piece is co-authored by Hari Ravikumar)

Continued in the next part

Dr. Ganesh is a Shatavadhani, a multi-faceted scholar, linguist, and poet and polyglot and author of numerous books on philosophy, Hinduism, art, music, dance, and culture.