[This is the second part of an exciting new series by Shrikant Talageri on India’s unique place in the world of numbers and numerals and its implications for the Out-of-India Theory of Indo-European Origins. In this part he delves into various written numeral systems, analyzes them in details and explains why the Indian numeral system was universally adopted all over the world, while all the other numeral systems fell into disuse.]

B. THE WRITTEN NUMERAL SYSTEM

Numbers (at least till three) are found in every language in the world. A written numeral system is something different from the mere concept of numbers. The numeral system used all over the world today is the system invented in India. In popular parlance, this is often described as follows: “India invented/contributed the zero“. But this is an extremely haphazard statement, at least when it comes to the importance of India in the history of numerals: the zero was also (at much later dates) independently invented in ancient Mesopotamia and Mexico (the Mayans). Also, it is quite a silly way of putting it. It sounds like some old-time fable: all the ancient civilizations of the Old World got together and decided “let us invent/contribute numbers“. China announced that it was contributing the numbers one, four and six. Egypt announced it was contributing two, three and nine. Mesopotamia announced it was contributing five, seven and eight. India, a little slow off the mark, was left with nothing to contribute. Then, the Indian representative had a brilliant idea: he immediately invented the zero, and announced “we contribute zero“!

The fact is, zero is just one essential part of the whole of the present day decimal numeral system which is used all over the world and which was invented/contributed by India and which is also the basis for the binary system which is used in computers (with a change of base from ten to two) . Numeral systems were independently invented by every highly developed civilization in the world: Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, Mexico and India. Most of the other civilizations of West Asia and Mediterranean Europe derived or developed their own numeral systems based on the Egyptian system. The numeral system of each civilization provides an indication of the stage of development of mathematical logic in each civilization, as we will see, and the Indian system represents the highest stage of development: the Egyptian system represents the first systematic stage of development, the Chinese system represents the second systematic stage of development, and the Indian system represents the third and final systematic stage of development.

The very idea of numbers contains the first seeds of any numeral system. We can imagine different societies from the most primitive times which had numbers (at least up to three in the simplest and most primitive system) but did not have any method of recording numbers in the form of a written numeral system.

The first primitive stage of recording numbers must have started in a pictorial form. In a primitive society, a man possessing, for example, 12 cows and 5 sheep thought of recording the fact by drawing 12 pictures of a cow and 5 pictures of a sheep. The very concept of representing numbers in writing (albeit pictorial) is the characteristic of this first stage.

In the second primitive stage, as society became larger and more complicated, the concept of numbers must have evolved from the concrete to the abstract. Thus, finding it tiresome to draw 12 pictures of a cow and 5 pictures of a sheep, the man in a society at a more developed stage conceived the idea of representing each unit by an abstract picture (most logically a simple vertical or horizontal line): thus 12 lines followed by the picture of a cow, and 5 lines followed by the picture of a sheep. The concept of abstract numbers, as opposed to numbers as an intrinsic aspect of some concrete material unit, is the characteristic of this second stage.

In the third primitive stage, as the number of units became much larger and more cumbersome, it would be tiresome to keep track of the number of individual pictures. Draw a series of 152 vertical lines in a row and try to count them again, to see how clumsy it would be and how susceptible to counting errors! This must have led to the evolution of numbers from the individual unit to the collective unit. This can be seen even today in a system of keeping scores which is still quite commonly used: after four vertical strokes to indicate four scores, the fifth stroke is a horizontal stroke drawn across the earlier four strokes, indicating five or a full hand. After that the sixth score is recorded by another vertical stroke at a little distance from the first hand. The concept of an abstract unit consisting of a collection of a certain fixed number of individual abstract units is the characteristic of this third stage.

[This fixed number was different in different primitive societies: the most common, natural and logical number was ten in most societies since human beings have ten fingers on the hands for counting, but it could also be (and was so in some societies) five (one full hand) or twenty (the total number of fingers on both hands and feet). If human beings had had twelve fingers instead of ten, the natural numeral system would have been mathematically even more effective, since twelve is divisible by two, three, four and six, while ten is divisible only by two and five. And it would also have fit in with some other aspects of nature, such as the twelve months in a natural year, the twelve tones in a natural octave, etc.].

From this point start the three systematic stages of development of the numeral system:

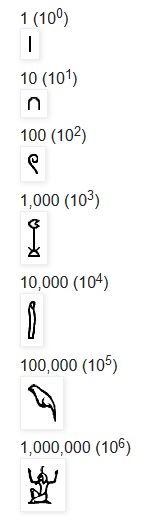

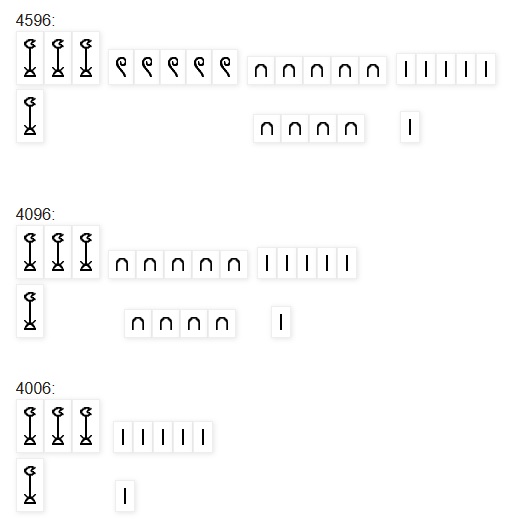

1. The Egyptian numeral system represents the first stage of development. This stage involves the invention of a continuous recurring base. The base (as in most cultures) is ten. The main problem in any numeral system that was solved by the Egyptian system was the repetition of symbols beyond nine times. The Egyptian system had one symbol for one, another for ten, another for hundred, and so on, for subsequent multiples of ten (see chart). Each symbol could be repeated as many as nine times to represent the next number in the series. Thus to write 4596, first the symbol for thousand was repeated four times, then the symbol for hundred five times, then the symbol for ten nine times, and finally the symbol for one six times:

The symbols for 1 (100), 10 (101), 100 (102), 1, 000 (103), 10, 000 (104), 100, 000 (105), and 1, 000, 000 (106), respectively are as follows:

2. The Chinese numeral system represents the second stage of development. Like the Egyptian system, it has symbols to represent the numbers one, ten and multiples of ten. But it eliminated the need to repeat these symbols from two times to nine times to represent multiples of the symbols. The logic used was the same as the logic involved in replacing the twelve pictures of a cow (in the primitive stage explained earlier) with twelve abstract symbols for one (usually a vertical line) followed by the picture of a cow. Here the repetitions of the symbol were replaced by new symbols representing the number of repetitions. That is, any symbol (one, ten, hundred) required to be repeated only in eight ways: twice, three times, four times, five times, six times, seven times, eight times or nine times. The Chinese system therefore also invented eight new symbols to represent the abstract numbers two to nine, and merely placed the new symbols before the original symbols (ten, hundred, etc.) as required in representing any number. Thus to write 4596, the Chinese would place the following symbols in the following order: four, thousand, five, hundred, nine, ten, six. The following chart shows some of the Chinese numerals (a sixth century book gives these symbols from 102 to 1014, see below, but in practice, the Chinese followed, and still follow, in cases where the traditional numbers are still used, different systems of combinations of symbols to express large numbers. In this, many of the symbols given below have much larger values in modern usage):

1-9: 一 二 三 四 五 六 七 八 九

101: 十

102: 百

103: 千

104: 萬

105: 億

106: 兆

107: 京

108: 垓

109: 秭

1010: 穰

1011: 溝

1012: 澗

1013: 正

1014: 載</strong

Thus:

4596: 四 千 五 百 九 十 六

4096: 四 千 九 十 六

4006: 四 千 六

3. The Indian numeral system represents the third and final stage of development. The Chinese system had eliminated the need for repeating symbols from two to nine times to represent the next number in any series, but the system still required a fresh symbol to represent each next multiple of ten (i.e. 102, 103, 104…). The Indian system, by using a fixed positional system and a symbol for zero, eliminated this need to invent an endless number of symbols and made it possible to represent any finite number without any limit by a simple system of ten symbols (1-9 and 0).

- १

- २

- ३

- ४

- ५

- ६

- ७

- ८

- ९

- 0

The shapes of the actual symbols used do not matter: the numeral symbols are different in different Indian languages, and even the “Devanagari” numeral symbols in Hindi and Marathi, for example, have noticeably different shapes. The Indian numeral system was borrowed by the Arabs, who gave the symbols different shapes again, and later by the Europeans from the Arabs with other similar changes in the shapes. It may be noted, moreover, that some of the Devanagari (Sanskrit) numerals, which were the ultimate basis for the shapes of the symbols in all the other systems, clearly bear some resemblance to the initial letters of the respective Sanskrit number words: १ (ए), ३ (त्र), ५ (प), ६ (ष).

The binary system used in computers is a direct derivative of the Indian decimal system, with a change of base from ten to two: so, while the Indian decimal system has ten symbols (nine number symbols and a zero), the binary system has two symbols (one and zero), and the place values from the right to the left are not 1, 10, 100, 1000…. as in the decimal system, but 1, 2, 4, 8, 16…. .

Thus, in the binary system:

4596: 1, 000, 111, 110, 100.

4096: 1, 000, 000, 000, 000.

4006: 111, 110, 100, 110.

Clearly, while the binary system is useful in the world of computers, the decimal system is more practical for the daily use of human beings.

Now, if the Egyptian, Chinese and Indian systems represented the three logical stages in the development of a logical and practical numeral system, what did the numeral systems of the other civilizations represent? They represented deviations from the logical line of thinking, which is why their systems ultimately failed to acquire the universality of the Indian system.

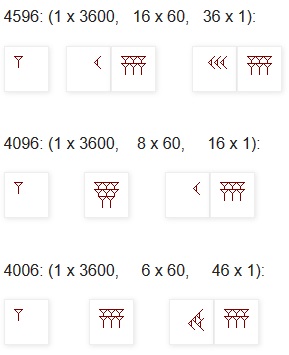

1. The Babylonian numeral system:

The Babylonian (Mesopotamian/Cuneiform) numeral system, to begin with, had symbols for one and ten, and derived the numbers in between accordingly by repetitions:

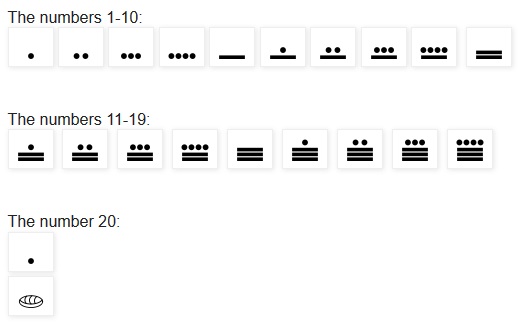

The numbers for 1-10 are as follows:

The symbols for the tens numbers were also formed by repeating the symbol for ten.

The numbers for 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60:

And here was the catch: although the Babylonians had symbols for one and ten, their numeral system was not a decimal system (i.e. with a base of ten): it was a unique sexagesimal system (i.e. with a base of sixty)! Therefore their place values from the right to the left were not 1, 10, 100, 1000…. as in the decimal system, but 1, 60, 3600, 72000…. . Therefore, the symbol for one also served as the symbol for sixty, three thousand six hundred, seventy-two thousand, etc., depending on its position from the right in a composite numeral. The Babylonian system had three main faults:

- Just as the binary system (howsoever vital to computers and cyber technology) is too small for normal human usage, a sexagesimal system was too large and unwieldy for human usage and computation.

- To be effective even as a sexagesimal system, it should have had sixty symbols (for the numbers from one to fifty-nine, and one for zero), but it only had symbols for one and ten. Of course, the symbols, as we can see above, were joined together, but that did not really improve matters. And, even if there had been sixty different symbols, it would still have been too large and unwieldy for common human use.

- It did not have a symbol for zero. Therefore, it was not clear whether the symbol for one, all by itself and without being a part of a larger composite numeral, represented one or sixty or three thousand six hundred or seventy-two thousand or something bigger. In the Indian system, you can distinguish not only between 1, 10, 100, 1000, etc. because of the zeroes, but also between 40006, 40060, 40600, 46000, 4006, 4060, 4600, 406, 460 and 46. In the Egyptian and Chinese systems, even without the zero, all these numbers could be distinguished because the “position” of each individual number in the composite numeral was distinguished by a different symbol (for ten, hundred, thousand, etc.). The Babylonian system, although it was effectively used by the Babylonians for their different purposes, was a very faulty system in which, for example, not only could the same symbol represent 1, 60, 3600, 72000, etc., but the same combination of symbols could represent, to take the simplest example, 3601, 3660 and 61.

[Later in time, a zero symbol was invented, but it was not really properly understood, and was used only at the end of a composite numeral].

To continue the same examples of the numbers already seen in the other systems, the Babylonian system would write them as follows:

2. The Mayan numeral system:

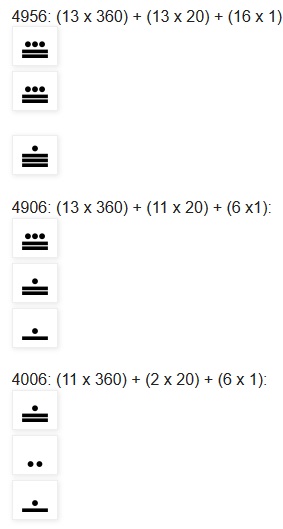

Like the Babylonian numeral system, the Mayan (Mexican) numeral system also was not a decimal system (i.e. with a base of ten): it was a vigesimal system (i.e. with a base of twenty). Basically it had only three symbols, for one, five and zero, and the other numbers between one and twenty were written by repetitions of symbols. The Mayans also, thus, had discovered the principle of using a zero symbol. The place values in this system, (written not from the right to the left as in other systems, but from the bottom to the top), were not 1, 10, 100, 1000…. as in the decimal system, but 1, 20, 400, 8000…. (at least we must assume this theoretically here for the moment for our study of the numeral system, but this was not strictly accurate as we will see presently). The symbols from one to nineteen were as follows:

The Mayan system was basically a marvelous one: it had a strict positional system as well as a fully-developed zero concept and symbol; but it suffered from certain faults:

- To be fully effective as a vigesimal system, it should have had twenty symbols (for the numbers from one to nineteen, and one for zero), but it only had symbols for one, five and zero. The numbers in between one and twenty were written by repetitions of the symbols for one and five.

- For religious reasons, to fit in with the (roughly) 360 days in the calendar, the Mayans tweaked the base of the vigesimal system, so that instead of the place values in this system (written from the bottom to the top) being 1, 20, 400, 8000, 160000…. as in a regular vigesimal system, they were 1, 20, 360, 7200, 144000…. . In short, there was a break in the regularity of the recurring base at the very second multiple, so that the third place from the bottom represented 360 instead of 400, and after that all the subsequent bases continued at multiples of twenty: The numbers for 1, 20, 360, 7200, 144, 000, and 2, 880, 000 are as follows:

We have already seen certain numbers written in all the numeral systems discussed so far. The following are their forms in the Mayan numeral system:

3. The Egyptian-derived Mediterranean and West Asian Numeral Systems:

The Egyptian numeral system that we have already examined (called the Hieroglyphic numeral system) was adopted by the Greeks, and from the Greeks by the Romans, with modifications. The Egyptian Hieroglyphic numeral system, as we have seen, was at the first stage of development of a logical and complete system of numerals. But unfortunately, instead of developing it in the right direction and reaching at least the second stage of development, as for example represented in the Chinese numeral system, the Greeks and the Romans went off at a tangent from the logical line of development in trying to simplify and “develop” the Hieroglyphic numeral system.

At the same time, the Egyptians themselves “developed” another system of numerals, distinct from the earlier system, called the Hieratic numeral system. This system was adopted by the Greeks (and called the Greek Ionian numeral system in opposition to the earlier Greek Attic numeral system derived from the Egyptian Hieroglyphic numeral system) and by all the other prominent civilizations and cultures of the Mediterranean area and West Asia (including the Israelites and the Arabs) except the Romans. This represented another “development” at a tangent from the logical line of development:

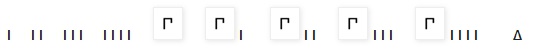

a. The Attic Greek numeral system: The Greeks adopted the Egyptian Hieroglyphic numeral system, replacing the Hieroglyphic symbols with Greek letters (being the first letters of the respective Greek numbers), as follows:

The numbers 1, 10, 100, 1000, 10000:

Ι Δ Η Χ Μ

The first ten numbers 1-10 should naturally have been written as follows:

Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Ι Δ

However, the Greeks decided to simplify or “develop” the numeral system to reduce the number of repetitions of a symbol within a compound numeral. Their solution was to invent mid-way symbols between 1, 10, 100, 100, 10000, etc., as follows:

The numbers 5, 50, 500, 5000, 50000: Therefore, the Greek symbols for the first ten numbers 1-10 were as follows:

Therefore, the Greek symbols for the first ten numbers 1-10 were as follows:

The three numbers that we saw in the different systems already described would appear as follows in the Greek system:

b. The Roman numeral system: The Romans adopted the Attic Greek numeral system, providing their own symbols for the Greek ones:

1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500, 1000, 5000, 10000, 50000, 100, 000:

I V X L C D M V X L C

[The numbers 5, 000 onwards have a horizontal line above the symbol, but due to lack of such a font, the symbols here have been underlined]

However, the Romans decided to “develop” the system further. They found even four repetitions of a symbol within a compound number (as in IIII for four and VIIII for nine) too much, and decided to reduce the fourth repetition by introducing a minus-principle: instead of having the bigger number followed by the smaller number four times, they decided to place one symbol of the concerned smaller number before the bigger number to indicate “minus one”. Thus:

1-10:

I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X

Tens 10-100:

X XX XXX LX L LX LXX LXXX XC C

Hundreds 100-1000:

C CC CCC CD D DC DCC DCCC CM M

1000:

M

And so on. The three numbers already shown in the other systems would appear as follows in the Roman numeral system:

4596: MVDXCVI

4096: MVXCVI

4006: MVVI

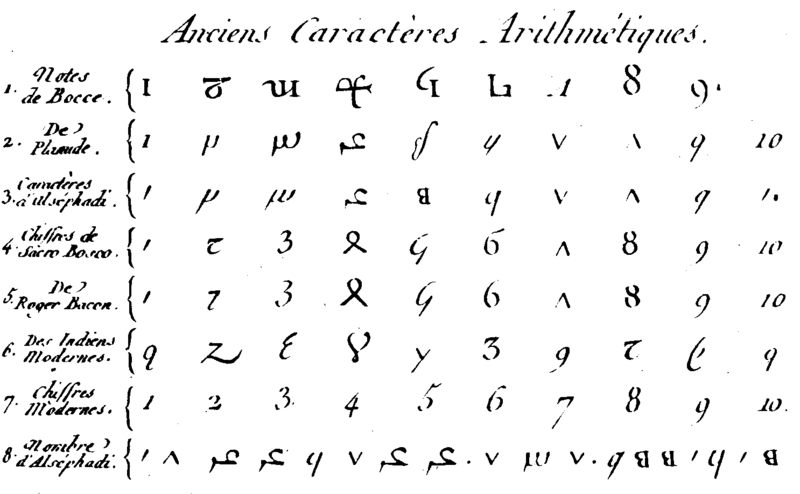

c. The Hieratic numeral system: The Egyptians themselves invented another new numeral system, a sort of shorthand numeral system, where they had nine symbols for the numbers 1-9, nine symbols for the numbers 10-90, nine symbols for the numbers 100-900, and so on, based on the letters of the Hieratic script. This numeral system was then adopted by the Ionian Greeks, using the symbols of their alphabets to represent the numbers. The Hieratic numerals and the Ionian Greek numerals are shown in the charts below:

The same system was also adopted by almost all the cultures and civilizations of the Mediterranean area and West Asia (except the Romans), including the Arabs and the Israelites, using the symbols of their respective alphabets.

The same system was also adopted by almost all the cultures and civilizations of the Mediterranean area and West Asia (except the Romans), including the Arabs and the Israelites, using the symbols of their respective alphabets.

This exposition of the numeral systems of the world makes it clear why the Indian numeral system was universally adopted all over the world, and all the other numeral systems fell into disuse (although still used as secondary symbols in scholarly works or for other particular and restricted purposes, as for example the Roman numeral system in western academic and religious works or a much-modified Chinese numeral system in China).

To be continued …

The article originally appeared here and has been republished with permission.

Featured Image: Wikipedia

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Shrikant Talageri is a scholar and acclaimed author of The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis, the seminal work on the Aryan Invasion debate. His latest work is “Rigveda And Avesta The Final Evidence.”