Preface

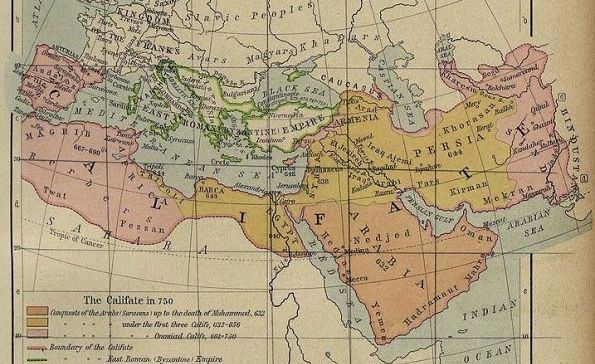

By 1000 CE, the Turks were already on their way to becoming the primary spearhead of Islam against the Hindus of India, the heathen civilizations of Central Asia, and the Christians in the West. The Mongol conquests of Il-Khan Hülegü in West Asia put an end to the Arab Islamic Caliphate in Baghdad. This was followed by the ascendency of the Turkic Osman Empire, at which point the power center within Islam completely shifted from the Arab world to the Turkic world.

After the Osman Sultan Mehmet-II [1] took Constantinople from the Byzantine Christians he declared himself the Khalifeh ül-Rasul Rab al-A’alamin, i.e. Caliph of Islam. This Osman Caliphate lasted until the last century when it was ended by the secular movement of Mustafa Kemal. Now, 90 years later, the Islamic Caliphate has re-emerged in its former west Asian heartland, where it held sway prior to the Mongol conquests under Dr. Abu Bakr, who claims descent from the same clan as the founder of Islam. The goriness and swiftness of its advance is comparable only to its earlier counterpart from around 1300 years ago.

One of the major thrusts of the Army of Islam under the early Arab Caliphate was in Central Asia. This came at the expense of the greater Indic civilization and still leaves its mark on Bharata by cutting our nation off from its natural sphere of influence, Central Asia, or what the Hindus called Uttarāpatha. Now the new Caliphate has already placed Bharata in it crosshairs, even as its commander, Ibrahim Awwad al-Badri, made this clear recently. Against this backdrop it is useful to examine the history of these earliest Islamic attacks on Central Asia.

Triumphant march of Islam in Central Asia under Qutayba bin Muslim

Within 20 years from the death of Mohammed, the founder of Islam, the army of Islam had largely destroyed the powerful Zoroastrian Empire of the Sassanians centered in Iran. While the exact reasons for this dramatic collapse of the Iranians before the Mohammedan charge remains unclear, it is conceivable that the death toll from the Justinian plague caused by a particularly virulent strain of the bacterium Yersinia pestis greatly weakened the ability of the former to mount an effective response.

In contrast, ensconced in the desert oases, the Arabs seem to have been shielded to a greater extent from the plague. The Army of Islam made its attempts to invade inner Eurasia and central Asia starting around 650 CE. In a quick-moving assault they pursued the Iranian Shah Yazdegird into Khorasan (Northeastern Iran). He took refuge in the city of Merv, where he was murdered by a Christian commoner for his possessions. With this the curtains came down on the Zoroastrian state, though its remnants kept fighting bravely for a while against Islam. The city of Merv was taken by the Moslems who settled 50,000 Arab families therein by dispossessing the Zoroastrians of their prized properties and farmland. Thus, they created a base for waging demographic warfare to go hand in hand with their military objectives. Shortly after the death of Yazdegird, his sons fled towards China, while the Arabs launched a series of raids into the Eastern limits of the Sassanian territory around 655CE, and crossed the Amu Darya River into central Asia. Here, the cities such as Bukhara and Samarkand fell in their sight, with their chief targets being the richly endowed Bauddha, āstika and Zoroastrian temples and religious sites.

One of the major thrusts of the Army of Islam under the early Arab Caliphate was in Central Asia. This came at the expense of the greater Indic civilization and still leaves its mark on Bharata by cutting our nation off from its natural sphere of influence, Central Asia, or what the Hindus called Uttarāpatha.

This period was also one of great turmoil on other fronts: Kashmir was going through a phase of relatively weak rulers and so was the rest of northern India after the death of Harṣhavardhana. This prevented Indian military power from being effectively projected in Central Asia. A new power, Tibet, had emerged and was on its way to being a great power, boosted by their first emperor Songtsen Gampo. The Chinese were launching a massive thrust into central Asia and towards greater India as part of the expansionist policies of the Tang emperor Gaozong [2].

Thus, the local powers in Central Asia facing various new political vectors around them were particularly vulnerable to the assaults of the surging Moslems. Despite this, several of the small principalities with Bauddha, āstika and Zoroastrian affinities boldly fought the Arabs preventing them from making substantial gains in the period between 655-705 CE. Among these was Shubhakara Siṃha, who was the young ruler of a kingdom in what is today Northern Afghanistan and Southern Tajikistan. He put up a bold fight to repulse the Arab foray into his lands [3]. In 682 CE, the local struggle against the Islamic assaults was also strengthened by the resurgent heathen Gök (Blue) Turks united by their Khan Qutlugh Eltrish, who helped repulse a Moslem thrust towards Khwarizm and Samarkand.

Finally, in 705 CE after several failed attempts to effectively penetrate Central Asia, the Caliphate appointed Qutayba bin Muslim as the chieftain of Merv. This Arab warlord led a series of brutal jihads to capture the key civilizational centers of Central Asia. The local rulers met at Khwarizm to plan a defensive strategy but it appears they were unable reach a proper plan for united action – it clearly seems they lacked a proper estimate of the threat before them. By the time of his death, Qutayba had taken Bukhara, Balkh, Samarkand and other major Khwarizmian cities in quick succession. In each of the places he massacred part of the population and took over the best quarters of the cities and settled Moslems brought from Arabia in those. The rest were made to accept Mohammedanism in return for their heads remaining intact on their shoulders. They were then drafted as cannon fodder for the assault on the next city.

In addition to the forced conversions, Qutayba took every step to erase all signs of Indic and Iranic civilization in those regions. The Moslem scientist Al-Biruni himself informs us that in the major cities of Khwarizm, Qutayba demolished huge libraries and burnt their numerous Indic and Iranic texts. Al-Biruni also mentions that he systematically killed all the Indic and Iranian scholars who manned those libraries. It is of interest to note that certain Western scholars such as the Wilhelm Barthold have claimed that these events did not happen and tried to whitewash the violence of Qutayba. However, there are several accounts from the Moslem sources themselves of the brutality of Qutayba’s actions: In 706 CE as a prelude to the assault on Bukhara, he took Paikend, which was bravely defended by heathen Iranian and Turkic fighters. He then killed all the males and took the women and children as booty. Many were sent to the slave markets at Kufa, Basra and Merv and it is said that the prices of Central Asian slaves fell drastically by several dirhams. In another assault that followed at the height of winter on the Bukhara oasis, the Moslems took many captives who refused to accept Islam; thereupon they were stripped and left to freeze to death. In 709 CE Qutayba finally took Bukhara after much fighting. Those who did not lose their homes were forced to house Moslems and feed them. Then in 712 CE he demolished the main temple of Bukhara, which was a holy site for both Bauddhas and āstika-s [4]. He built a Masjid using the material from it.

Certain Western scholars such as the Wilhelm Barthold have tried to whitewash the violence of Qutayba.

Jihad after Qutayba bin Muslim’s death

In 715 CE, Qutayba bin Muslim was killed in an inter-Moslem conflict for opposing the accession of the next Caliph (as Samuel Huntington said, Islam is bloody within and without). But this did not mean that the jihad ended in Central Asia. Rather, new Ghazis or holy warriors volunteered from the Arab ranks to join the fight against the infidels in Central Asia. Without military resources to face the powerful Arab onslaught, the local rulers turned to the “superpower” of the day—China.

The Tang emperors saw in it an opportunity to extend their power, but little real help to the heathens was forthcoming from those quarters. However a few surviving Indic and Iranic scholars found shelter in the cīna country. We know of this from the biographical account of the famous Bauddha tAntrika teacher Amoghavajra who was born in 705 CE in Samarkand to a Brāhmaṇa father from either Prayāga or Kāśī and an Iranic mother. His father died in course of the siege of Qutayba in 715 CE, and the young Amoghavajra fled with his mother to the cīna-deśa. Despite no real aid from any quarter, the local rulers did not give up their religion and fought manfully to defend their way of life. We get a glimpse of their difficulties from the letter Ghourek, the Iranic ruler of Samarkand, sent in 718 CE to the Tang emperor politely complaining of his not sending aid:

“Your subject [Ghourek], like the grass and soil trampled by your horses for a million li, submits to the godly emperor who, by the grace of the heavens, rules the entire world. The members of my family, and the various Hou kingdoms, have long been sincerely devoted to your great empire…Now for 35 years since we have fought ceaselessly with the Arab brigands; each year we have sent large armies of infantry and cavalry on campaign, without ever enjoying the good fortune of receiving soldiers sent to help us by your imperial kindness. For more than six years, the general commanding the Arabs has come at the head of a numerous army; we fought him and tried to defeat him, but many of our soldiers were killed or wounded; as the infantry and cavalry of the Arabs were numerous…I returned behind by walls to defend myself. The Arabs then besieged the city, placing 300 ballistas against the walls and at 3 points they dug deep ditches, trying to destroy our kingdom.”

In 719 CE, central Asian rulers, Nārāyaṇa (Southern Tajikistan), Ghourek (Samarkand) and the Indianized Turk Tuṣārapati (Bukhara) put a firm resistance against the Arabs and blocked their advance. With this ended the first chapter of the Moslem assault on central Asia. Noting this, the Tang emperor sent them words of encouragement and acknowledged them as independent kings but did little else to help their cause. They finally received succor only when Khan Su-lu became the ruler of the Türgesh Turks and organized a combined heathen front to blunt the Arab advance.

Some conclusions

In conclusion, the incidents from the early phase of the Islamic Caliphate’s advance into Central Asia are mirrored in many ways by the advance of the current Caliphate, replete with slaughter and enslavement of the Yezidis, one of the last remnants of the old Iranic tradition in the region.

It is also important to note that the heathens of Central Asia, the Indic, Iranic and Turkic, did not “accept” Mohammedanism as though it was gift being conferred on them.

Moreover, Hindus need to note that these early invasions were at the expense of regions which were within their sphere of influence and peopled by their co-religionists. Today this memory is largely lost in the collective Hindu awareness. It is also important to note that the heathens of those regions, Indic, Iranic and Turkic, did not “accept” Mohammedanism as though it was gift being conferred on them– a view subtly propagated by certain western scholars in an attempt to create the image of a great flowering of an Arab civilization in Central Asia [5].

First, they fought tooth-and-nail to try to halt the Islamic whirlwind sweeping into their lands from the Arabian deserts. Second, the loss of heathen civilization in these regions was ultimately because their libraries were specifically targeted and destroyed, and their scholars killed. Third, while their knowledge systems were destroyed, what remained was appropriated by Islam and is accepted by its proponents (both Mohammedans and their non-Mohammedan supporters) as being part of the Islamic civilization (e.g. several aspects of Al-Biruni’s science and the Shah Namah). Finally, from a geopolitical viewpoint the memory of the struggle in Central Asia should inform Hindus that their ultimate objective should be a state that reasserts itself in those regions as in the past.

References:

1: His brother Yusuf Adil Khan fled Turkey to evade assassination and founded the Adil Shahi Sultanate in South India. It was a major adversary of the great Hindu empires, namely Vijayanagara and the Marāṭhā Empire founded by Chatrapati Sivājī.

2: Gaozong was close to Turkic clan from the region to the North of China and as a youth liked to lead a life like them in camp grounds rather than in the palace. He had inherited the Turkic mounted cavalry divisions his father had built and this greatly aided his military ambitions.

3: He is said to have been the descendant of the ruling clan from a small kingdom in what is today the border between modern Madhya Pradesh and Orissa. He went on to renounce his kingdom and become a great mantrayāna teacher who transmitted these traditions to China and from to Japan.

4: One may see “Hindu Gods in Western Central Asia A Lesser Known Chapter of Indian History” by S.P. Gupta from evidence for Hindu images from here.

5: As an example one may consider the recently published volume: “Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane” by S. Frederick Star. It gives an effusive account of the “Islamic golden age” in Central Asia with claim that the knowledge systems created there contributed fundamentally to Indian knowledge among others.

The author is a practitioner of sanAtana dharma. Student, explorer, interpreter of patterns in nature, minds and first person experience. A svacchanda.