The drain of wealth out of India by the British is a well known fact that has been meticulously recorded by historians and economists. However, the drain of wealth originally started with the Islamic invaders who carted off prodigious quantities of wealth to their Arab, Persian, Turkic and Central Asian homelands for a longer period than the British in India. Muslim invaders also carried away millions of Hindus as slaves and Muslim rulers exported Hindu slaves. India was the world’s leading economy from 1 CE to 1000 CE but in the second millennium it lost the top spot to China after the Islamic invaders razed India’s universities, disrupted the economic systems and caused havoc in religious and social life.

Not many realise that from the year 712 CE (when Sindh became the first Indian kingdom to be conquered by a Muslim army) to the middle of the 16th century, India was a part of the Islamic Caliphate. The areas of the country under Muslim occupation were tributaries of the Islamic empire. Incalculable amounts of wealth and numberless slaves were sent annually to the countries that India’s Muslim rulers owed allegiance to.

“This is how the money and resources, extracted from the sweat and toil of non-Muslim subjects of India, used to be siphoned to the treasuries of the Islamic Caliphate in Damascus, Baghdad, Cairo or Tashkent, to the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina, and to the pockets of the Muslim holy men throughout the Islamic world. At the same time, the infidels of India were being reduced to awful misery,” writes M.A. Khan in ‘Islamic Jihad: A Legacy of Forced Conversion, Imperialism and Slavery’.

To their credit, the Mughals were the first Muslim dynasty in India to declare independence from the Islamic Caliphate. But this was not because of any love for India (on the contrary the first Mughal emperor Babur hated India so much that he stated his desire to be buried in Kabul after his death). The Mughals broke free because of two reasons. One, they had become too large and powerful to remain a subsidiary of a distant Caliphate; secondly, the hedonistic Mughal emperors did not want to send the greater portion of their vast wealth overseas when they could spend it all on themselves – no questions asked.

The quantum of wealth that flowed into the Mughal treasury was enormous. Here’s what the historian Abul Fazl wrote about India’s wealth: “In Iran and Turan, where only one treasurer is appointed, the accounts are in a confused state; but here in India, the amount of the revenues is so great, and the business so multifarious that 12 treasuries are necessary for storing the money, nine for the different kinds of cash-payments, and three for precious stones, gold, and inlaid jewellery. The extent of the treasuries is too great to admit of my giving a proper description with other matters before me.” (2)

However, contrary to the claims of leftists, liberals and fraudsters like the Hindu-hating Audrey Truschke, the drain of wealth continued. The sending of tributes had ended but the one-way flow of India’s wealth kept going west in different forms. “Besides sending revenue and gifts to the caliphal headquarters of Damascus, Baghadad, Cairo or Tashkent from India, Islam’s holy cities of Mecca and Medina amongst others also received generous donations in money, gifts and presents even in the Mughal period, when the Indian rulers had declared their independence from foreign overlords,” explains M.A. Khan.

Mughals – Drain game

Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, in his autobiography Baburnama records the gifts and presents he had sent “in the cause of God” to the holy men of Samarkand, Khurasan, Mecca and Medina.

Shortly after his victory over the last Delhi sultan Ibrahim Lodhi, which gave the Mughals the keys to the imperial treasury at Agra, Babur virtually emptied the treasury through his generosity, which of course extended only to Muslims.

Babur writes in his autobiography Baburnama: “Suitable money gifts were bestowed from the treasury on the whole army, to every tribe there was, Afghan, Hazara, Arab, Balluch etc to each according to its position. Every trader and student, indeed every man who had come with the army, took ample portion and share of bounteous gift and largess. And indeed to the whole various train of relations and younger children went masses of red and white (gold and silver), of plenishing (furniture and furnishings), jewels and slaves.” (3)

Many gifts went to Babur’s extended family in his native Uzbekistan, modern Tajikistan, modern Xinjiang in China and Arabia. “Valuable gifts were sent for the various relations in Samarkand, Khurasan, Kashghar and Iraq. To holy men belonging to Samarkand and Khurasan went offerings vowed to God; so too to Makka and Madina.” (3)

In Afghanistan, where Babur wandered many years during his youth, every single citizen was rewarded. The amount disbursed must have been huge. “We gave one shahrukhi (silver coin) for every soul in the country of Kabul and the valley-side of Varsak (in Afghanistan), man and woman, bond and free, of age or non-age.” (3)

Presents of jackets and silk dresses of honour, of gold and silver, of household furnishings and various goods were given to those from Andijan, Uzbekistan, and to those who had come from Sukh and Hushlar, “the places whither we had gone landless and homeless”. Gifts of the same kind were given to the servants of Qurban and Shaikhl and the peasants of Kahmard (in Afghanistan). (4)

It is clear that hearing of Babur’s windfall, multitudes of Central Asians and Afghans had travelled to Delhi to claim cash, material gifts and slaves. Those who couldn’t trudge the vast distance were supplied cash in the comfort of their homes.

According to the Persian historian Firishta, “Babur left himself stripped so bare by his far-flung largesse that he was nick-named Qalandar.”

Haj windfall

Modern India’s secular rulers granted hundreds of crores for Indian Muslims to perform the Haj. This annual ripoff continued for decades. This involved building an entire Haj terminal in Mumbai. Despite the unconstitutionality – and blatant hypocrisy – of secular governments catering to a purely religious pilgrimage, the appeasement continues. Several Indian states, including Delhi, have spent vast sums to construct Haj houses. However, all these efforts by Hindu dhimmis pale before the Mughal Haj tours.

During the Mughal era on an average 15,000 pilgrims every year visited Mecca to perform Haj. According to a Mughal official, these pilgrims went on Haj “at great public expense, with gold and goods and rich presents”. Mughal emperors sponsored the pilgrimage to “stand out as defenders of Islam”. (5)

This religious sponsorship began after Akbar conquered Gujarat in 1573 and the Mughal Empire got access to the port of Surat. An imperial edict proclaimed that “the travelling expenses of anybody who might intend to perform the pilgrimage to the Sacred Places should be paid”. (5)

In 1576, a Mughal Haj caravan left Agra with its party of sponsored pilgrims and an enormous donation of Rs 600,000. (6) To understand how large this amount was, the average salary of a chariot driver that year was Rs 3.50 per month and a barber earned Rs 0.50 a month.

In 1577, another Haj caravan left with a double bounty of Rs 500,000 and Rs 100,000 for the Sharif of Mecca, who was a descendant of Prophet Mohammad’s grandson Hasan ibn Ali.

These gargantuan amounts of money caused many poor people from all over the Muslim world to flock to Mecca in 1577-78 to share the alms bonus. (6)

However, with great wealth comes great temptation. In 1582, Akbar discontinued the sponsored pilgrimage because of massive corruption both in Mecca and among his courtiers who were siphoning funds allocated for the Meccans.

Akbar’s great charities didn’t protect him from his own son Jehangir, who poisoned him to death. The new Mughal emperor reinstituted the sponsored tours. In 1622, Rs 200,000 was allocated for Haj. (7)

Jahangir writes in his autobiography Tarikh-i-Salim Shahi: “During the reign of my father, the ministers of religion and students of law and literature, to the number of two and three thousand, in the principal cities of the empire, were already allowed pensions from the state; and to these, in conformity with the regulations established by my father, I directed Miran Sadr Jahan one of the noblest among the Seyeds of Herat, to allot a subsistence corresponding with their situation; and this is not only to the subjects of my own realms, but to foreigners – to natives of Persia, Roum, Bokhara, and Azerbaijan, with strict charge that this class of men should not be permitted either want or inconvenience of any type.” (8)

Jehangir’s son and successor Shah Jahan was the least religious of the Mughal emperors. Although devoted to a life of luxury, debauchery and extravagant monument building, he too did his bit for the Ummah. Shah Jahan despatched to Mecca an amber candlestick covered with a network of gold and inlaid with gems and diamonds by his own artisans. It was a most gorgeous piece of work turned out by the craftsmen, worth Rs 2.5 lakh. (9)

Lavish gifts were also sent by other notables such as Mufti Ahmed Saeed, who in 1650 dispatched a diamond-studded candlestick and a 100 carat diamond. (7)

Aurangzeb: A cut above

The cruel and fanatic Mughal emperor Aurangzeb was perhaps the biggest Indian donor to Muslim lands. During the years 1661-67, he received at his court the kings of Persia, Balkh (in Afghanistan), Bukhara, Kashgar (in Xinjiang, China), Urganj (Khiva) and Shahr-i-Nau (in Iran), and the Turkish governors of Basra (in Iraq).

According to the Cambridge History of India, “His policy was to dazzle the eyes of these princes by lavish gift of presents to them and to their envoys, and thus induce the outer Muslim world to forget his treatment of his father and brothers. The fame of India as a soft milch cow spread throughout the middle and near East, and the minor embassies were merely begging expeditions.” (10)

On the embassies received and the return-embassies sent out, Aurangzeb spent in presents nearly Rs 3 million in the course of seven years, besides the large sums which he annually distributed at Mecca and the gift of Rs 1 million to Abdullah Khan, the deposed king of Kashgar, who had taken refuge in India in 1668 and died at Delhi in 1675. (11)

The Sharif of Mecca in particular used to send his agents to the Delhi court every year with the object of levying contributions in the name of the Prophet, till Aurangzeb’s patience was worn out and he stopped all donations to the Sharif. However, the flow of cash to Mecca continued – Aurangzeb sent his gifts to scholars and mendicants through his own agents.

Ripoff artists from the Islamic crescent

Mughal gift giving was a purely one-way street as far as the flow of wealth was concerned because the return gifts were pretty pathetic or at best ordinary and base. This is illustrated by an episode from the travelogue of Francois Bernier, the Frenchman who spent a considerable length of time in Delhi.

In 1664, the Christian monarch of Ethiopia sent an embassy represented by two ambassadors – an Armenian Christian named Murat and a Muslim merchant. They arrived in Delhi with the following ‘gifts’ – a mule skin, the horn of an ox, some arrack and a few famished and half-naked African slaves.

Upon receiving them, Aurangzeb presented the embassy with a brocade sash, a silken and embroidered girdle, and a turban of the same materials and workmanship; and gave orders for their maintenance in the city. Later at an audience, he invested each with another sash and made them a present of Rs 6,000. However, the fanatic that he was, Aurangzeb divided the money unequally – “the Mahomaten receiving four thousand roupies, and Murat, because a Christian, only two thousand”. (12)

And that wasn’t the end of Aurangzeb’s largesse. The cunning merchant solemnly promised Aurangzeb that he would urge his King to permit the repair of a mosque in Ethiopia, which had been destroyed by the Portuguese. Hearing this, the emperor gave the ambassadors Rs 2,000 more in anticipation of this service. (13)

Another interesting embassy came from the Uzbek Tatars. The two envoys and their servants brought some boxes of lapis-lazuli, a few long-haired camels, several horses, some camel loads of fresh fruit, such as apples, pears, grapes, and melons, and many loads of dry fruit.

The embassy which was led by two Tatars is described by Bernier as remarkable for the “filthiness of their persons”. He adds: “There are probably no people more narrow minded, sordid, or unclean than the Uzbek Tatars.”

But to Aurangzeb – who otherwise took the greatest offence at the smallest of slights – the wretched condition of the stinking embassy was a minor inconvenience that could be easily overlooked. All that mattered was that the beneficiaries were Muslims. So, in the presence of all his courtiers, he invested each of them with two rich sashes and Rs 8,000 in cash. Plus, a large number of the richest and most exquisitely wrought brocades, a quantity of fine linens, silk material interwoven with gold and silver, a few carpets, and two daggers set with precious stones.

According to the Twitter handle True Indology, in total Aurangzeb sent Rs 70 lakh to Muslim countries in six years. “This amount was almost twice the total revenue of England,” he writes. “This wasn’t foreign diplomacy since nothing but Islamic relics ever came back in return. The same Aurangzeb hanged to trees all Indian peasants who had defaulted on tax.”

Reality of Mughal rule

Leftist and secular historians are right about one thing – the Mughals were the richest dynasty of their time. But wealth has never been the yardstick for greatness. What they don’t see is the reality hiding in plain sight – India under the Mughals was one of the most miserable countries in the world. The relentless wars of the Mughals, in particular Aurangzeb’s 28 year war of attrition with the Marathas, and the loot of the peasantry were the prime reasons why the Indian economy was in tatters. In contrast to the previous Hindu rulers who taxed the farmers just 16 per cent of the total produce, the Mughal tax rate was 30-50 per cent, plus some additional cesses. (14)

As Bernier observed, gold and silver “are not in greater plenty here than elsewhere; on the contrary, the inhabitants have less the appearance of a moneyed people than those of many other parts of the globe”. This is perhaps the greatest indictment of Mughal rule – that the richest empire in the world also had the greatest mass of poor citizens.

Even during Jehangir’s time, the English ambassador Thomas Roe had noted the backwardness of the countryside. While his eyes dazzled at the mountains of diamonds, rubies and pearls displayed in the Mughal court, he also noted the generally large number of destitute people – all along the route from Surat to Delhi.

Under Aurangzeb’s rule the condition of the people worsened. It is “a tyranny often so excessive as to deprive the peasant and artisan of the necessaries of life, and leave them to die of misery and exhaustion,” writes Bernier. (15)

“It is owing to this miserable system of government that most towns in Hindoustan are made up of earth, mud, and other wretched materials; that there is no city or town which, if it be not already ruined and deserted, does not bear evident marks of approaching decay.” (16)

A significant reason for India’s growing backwardness under the Mughals – as it was under the previous Sultanate Period of 334 years – was a predatory and unsustainable economic system institutionalised by India’s new rulers who had supplanted the country’s ancient Hindu royal houses.

“Labourers perish due to bad treatment from Governors. Children of poor are carried away as slaves. Peasantry abandon the country driven by despair. As the land throughout the whole empire is considered the property of the sovereign, there can be no earldoms, marquisates or duchies. The royal grants consist only of pensions, either in land or money, which the king gives, augments, retrenches or takes away at pleasure.” (17)

According to historian K.S. Lal, All the resources available in India were fully exploited to provide comforts and luxuries to the Muslim ruling and religious classes. “Muslim chronicles vouch for this fact. They also vouch for the fact that the enjoyment of the Muslim elite was provided mainly by the poorest peasants through a crushing tax system.” (18)

Disconnect from the people

An episode from Shah Jahan’s life shows the contempt the Mughal court had for the people they ruled over and whose toil ensured their luxurious lifestyles.

In March 1628 a grand feast was held on the occasion of Nauroz, the Persian new year. All the grandees of the Empire were invited to participate. The members of the royal family were granted gifts and titles. Mumtaz Mahal, the imperial consort, was the recipient of the richest reward: she was granted Rs 50 lakh from the public treasury. His daughter Jahan Ara received Rs 20 lakh and her sister Raushan Ara, Rs 5 lakh.

During the period February-March alone, Shah Jahan expended altogether Rs 1 crore and 60 lakh from the public treasury in granting rewards and pensions. (19)

Two years later a terrible famine hit the kingdoms of Golconda, Ahmednagar, Gujarat and parts of Malwa, claiming the lives of more than 7.4 million citizens of the Mughal Empire. This makes it even greater than the British engineered famine of 1943 that killed between three and seven million Indians. The scale of the disaster was recorded by a lawyer of the Dutch East India Company who left an eyewitness account. (20)

The Mughal induced famine was a direct result of Shah Jahan’s scorched earth policies in his wars against the southern, western and central Indian kingdoms. To illustrate, when Mughal forces marched into Bijapur, they were ordered to “ravage the country from end to end” (21) and “not to leave one trace of cultivation in that country”. (22)

Corpses piled up along the highways of the empire as millions of hungry people were on the march looking for food. Proud father offered their sons free as slaves so the young may live but found no takers. Mothers drowned themselves in rivers along with their daughters.

In the backdrop of this disaster, the amount Shah Jahan distributed for famine relief was a paltry Rs 100,000. It was 10 per cent of what he gave his favourite wife Mumtaz Mahal as her fixed annual maintenance. His imperial treasury had Rs 6 crore in cash. The Taj Mahal cost more than Rs 4 crore to build. The famous Peacock Throne, covered with pearls and diamonds including the legendary Koh-i-Noor, was valued at Rs 3 crore.

If the reign of Rama, Ashoka (in his later years) and Harshavardhana could be considered the acme of generosity, the Mughal government was the exact opposite. Mughal rule was purely for the pleasure of the royal court, the emperor’s family and the vast harems. The total expense of the Mughal state plus autonomous princelings and chiefs was about 15-18 per cent of national income, writes the economist Angus Maddison. (23)

By one estimate, as many as 21 million people (out of a total population of approximately 150 million) constituted the predatory Mughal ecosystem – the court, family, army, harems, servants, slaves and eunuchs who produced nothing and only consumed. “As far as the economy was concerned, the Moghul state apparatus was parasitic,” writes Maddison. (24) It was a regime of warlord predators which was less efficient than European feudalism. “The Moghul state and aristocracy put their income were largely unproductive. Their investments were made in two main forms: hoarding precious metals and jewels.”

This large parasitic body was a huge drag on India. Bernier says the artisans who manufactured the luxury goods for the Mughal aristocracy were almost always on starvation wages. Incredibly, the price of what these artisans produced was determined by the buyers. Failure to comply often meant imprisonment or death. Similarly, the weavers who spun the world’s finest brocades and garments went about half naked.

Destruction of agriculture

The Mughal Empire was essentially agrarian in nature. “The Timurid dynasty’s wealth and power was based upon its ability to tap directly into the agrarian productivity of the Indian sub-continent,” writes American historian J.F. Richards. “Trade, manufacture and other taxes were much less important to the imperial revenues than agriculture, most estimates putting them at less than 10% of the total.” (25)

And how did the Mughals treat this critical sector on which the vast majority of Indians depended for their livelihood? Agriculture, in which India had excelled since ancient times as per Greek accounts, was in a terrible state under Aurangzeb. According to Bernier, “Of the vast tracts of country constituting the empire of Hindoustan, many are little more than sand, or barren mountains, badly cultivated, and thinly peopled; and even a considerable portion of the good land remains untilled from want of labourers; many of whom perish in consequence of the bad treatment they experience from the Governors.” (26)

“These poor people, when incapable of discharging the demands of their rapacious lords, are not only often deprived of the means of subsistence, but are bereft of their children, who are carried away as slaves. Thus it happens that many of the peasantry, driven to despair by so execrable a tyranny, abandon the country, and seek a more tolerable mode of existence, either in the towns, or camps; as bearers of burdens, carriers of water, or servants to horsemen. Sometimes they fly to the territories of a Raja, because there they find less oppression, and are allowed a greater degree of comfort.” (26)

Modern Indian historians concur that the Mughals were nothing less than rapacious. “The Mughal state was an insatiable Leviathan,” writes T. Raychaudhuri in ‘State and the Economy: The Mughal empire’. The result according to him was a peasantry consistently reduced to subsistence.

In 1963, Irfan Habib published ‘The Agrarian System of Mughal India: 1556–1707’ in which he viewed the Mughals as essentially extractive in character, taking the entire surplus from the farmers. Habib, a stridently anti-Hindu academic, states that the Mughal share of the crop varied between one third and one half, according to fertility. On top of this the zamindars’ share amounted nominally to 10 per cent of the land revenue in northern India and 25 per cent in Gujarat. (27)

Irrigation, the lifeblood of agriculture, was neglected. According to Maddison, the irrigated area was small. There were some public irrigation works “but in the context of the economy as a whole these were unimportant and probably did not cover more than 5 per cent of the cultivated land of India”. (28)

However, it would be incorrect to say the Mughals did nothing for agriculture. They built a mighty canal that transformed the geography and economy of a vast area, bringing prosperity to what used to be a barren desert. Unfortunately, it was not in India, but in Iraq.

In the late 1780s, even as the Mughal Empire was tottering under the blows of the Marathas, the chief minister of Awadh, Hasan Raza Khan, made a contribution of Rs 500,000 towards the construction of a canal known as the Hindiya Canal. When it was completed in 1803, it brought water to Najaf.

Lahore based historian Khaled Ahmed writes: “So big was the diversion of the water from the Euphrates that the river changed course. The canal became a virtual river and transformed the arid zone between the cities of Najaf and Karbala into fertile land that attracted the Sunni Arab tribes to settle there and take to farming.” (29)

What it boils down to is that while the Mughals did not build a single canal in India in 350 years, they built a life changing one in Arabia. And that was in the 1780s when the Mughal Empire was a vassal of the Marathas, and the British had captured large swaths of its eastern territories. Even in such a desperate situation, when they were on the verge of being ousted from Delhi, the Mughals saw fit to sneak money out of India.

Is further proof required to nail the lie that Mughals did not loot India’s wealth?

The Mughals were Muslims first and Muslims last. For better or for worse, their legacy continues to impact the Muslims of the subcontinent. As Khaled Ahmed says, “The custodian of the seminarian complex of Najaf and the mausoleum of Caliph Ali is a Pakistani grand ayatollah, appointed to his top position in deference to the fact that Najaf and Karbala were developed as a habitable economic zone by the Shia rulers of North India.” (29)

Mughals: The original racists

The Mughals are a misnamed dynasty – they are not Mongols or from Mongolia but are a Turkic people. The dynasty is more accurately described by early Western historians as the House of Timur. Babur’s homeland being Samarkand in Uzbekistan, the core of the Mughal court remained Uzbek, Central Asian and Persian (plus a smattering of Arabs and Turks) till the dynasty was extinguished in 1857. More significantly, the language of the Mughal harem was Turkic and that of the Mughal court was Farsi. There was very little that was Indian about it.

The Mughal harem was continuously replenished by fresh infusion of Turkic clansmen and brides coming in from Central Asia, mostly Uzbekistan. All that a dirt-poor Uzbek or Azerbaijani needed to do in order to become a noble was move to Delhi where he would be welcomed with cash, costly gifts, a large estate, countless slaves, a guaranteed annual income and a grand title. As the various independent accounts show, these new arrivals sent back to their extended family, friends and religious heads in Central Asia, vast quantities of wealth from their Indian jackpot.

While Hindus, barring a few Rajput kings who had allied themselves with the Mughals, lived a wretched existence, even the newly converted Indian Muslims were treated with contempt by the Mughals. As Bernier observes: “It should be added, however, that children of the third and fourth generation, who have the brown complexion, and the languid manner of this country of their nativity, are held in much less respect than newcomers, and are seldom invested with official situations; they consider themselves happy if permitted to serve as private soldiers in the infantry or cavalry.”

To illustrate, one of Babur’s premier commanders, Khwaja Kalan, was known for his open dislike of India. While returning to his homeland, as a parting shot, he had the following couplet inscribed on the wall of his residence in Delhi: (30)

“If safe and sound I cross the Sind,

Blacken my face ere I wish for Hind!

Clearly, by their actions and words, the Mughals remained a foreign occupying dynasty which was rooted in India only to live off the land. While contributing little to the country’s well-being, these parasitic rulers did everything to increase the people’s misery.

As Rukhsana Iftikhar of the University of Punjab, Lahore, observes in her study titled ‘Historical Fallacies’, in the reign of Shah Jahan, 36.5 per cent of the entire assessed revenue of the empire was assigned to 68 princes and amirs and a further 25 per cent to 587 officers. That is, 62 per cent of the total revenue of the empire was arrogated by 665 individuals. Therefore, the Mughal period was a golden age only for kings, princes and some individuals. The subjects of Hindustan, the real custodians of this State, were lucky if they had a loaf of bread. (31)

(This article is inspired by, and dedicated to, True Indology, who has been banned by Twitter India for consistently revealing the truth about India’s history and also because he was exposing the lies of the secular media and leftist historians.)

Sources

- British Library, http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/asian-and-african/2013/03/the-highjacking-of-the-ganj-i-sawa%CA%BCi.html

- Abul Fazl, Ain-i-Akbari, The Imperial Treasuries, http://persian.packhum.org/persian//main

- Annette Beveridge, Baburnama, Vol II, page 22

- Annette Beveridge, Baburnama, Vol II, page 529

- John Slight, The British Empire and the Hajj

- Wollebrandt Geleynssen, National Archives, The Hague

- John Slight, The British Empire and the Hajj

- Tarikh-i-Salim Shahi, page 16

- Radhakamal Mukerjee, Economic History of India, page 92

- Edward James Rapson, Wolseley Haig, Richard Burn, The Cambridge History of India, page 229

- Edward James Rapson, Wolseley Haig, Richard Burn, The Cambridge History of India, page 229

- Francois Bernier, Travels in the Mogul Empire, page 139

- Francois Bernier, Travels in the Mogul Empire, page 140

- Irfan Habib, Agrarian System of Mughal India, 1556–1707, page 38

- Francois Bernier, Travels in the Mogul Empire, page 226

- Francois Bernier, Travels in the Mogul Empire, page 227

- Francois Bernier, Travels in the Mogul Empire, page 5

- K.S. Lal, Theory and Practice of Muslim State in India, Chapter 5

- S.M. Jaffar, The Mughal Empire From Babar To Aurangzeb, Page 228

- A Famine in Surat in 1631 and Dodos on Mauritius: A Long Lost Manuscript Rediscovered, https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/full/10.3366/anh.2017.0422

- Muhammad Amin Kazwini, Padshah-nama, page 57

- Muhammad Amin Kazwini, Padshah-nama, page 135

- Angus Maddison, The Moghul Economy and Society, Chapter 2, Class Structure and Economic Growth: India & Pakistan since the Moghuls, (1971), page 5

- Angus Maddison, The Moghul Economy and Society, Chapter 2, Class Structure and Economic Growth: India & Pakistan since the Moghuls, (1971), page 6

- J.F. Richards, “Fiscal States in India Over the Long-Term: Sixteenth Through Nineteenth Centuries, 2001, page 4

- Francois Bernier, Travels in the Mogul Empire, page 225

- Irfan Habib, Agrarian System of Mughal India, 1556–1707, page 38

- Angus Maddison, The Moghul Economy and Society, Chapter 2, Class Structure and Economic Growth: India & Pakistan since the Moghuls, (1971), page 5

- Khaled Ahmed, The Shia of Iraq and the South Asian Connection, http://www.criterion-quarterly.com/the-shia-of-iraq-and-the-south-asian-connection/

- Annette Beveridge, Baburnama, Vol II, page 36

- Rukhsana Iftikhar, Historical Fallacies, South Asian Studies, A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol 28, No. 2, July – December 2013, page 367

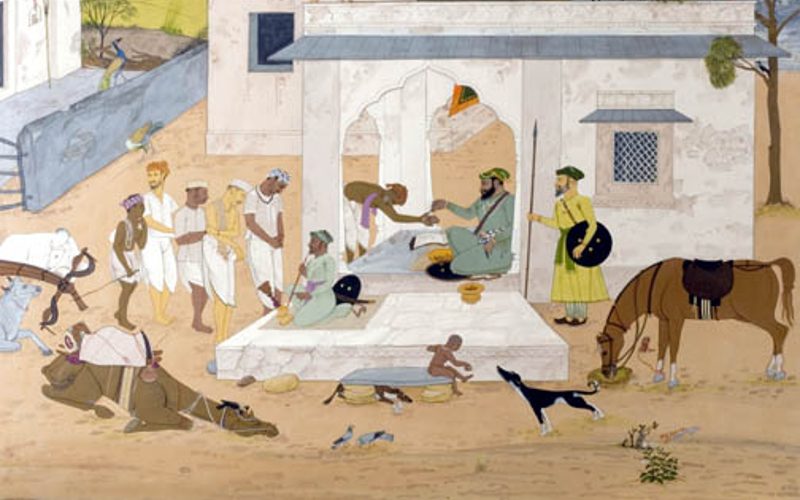

Featured Image: Facts Museum (Hindus forced to suffer humiliation in paying the Jizyah tax)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Rakesh is a globally cited defence analyst. His work has been published by the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi; Russia Beyond, Moscow; Hindustan Times, New Delhi; Business Today, New Delhi; Financial Express, New Delhi; BusinessWorld Magazine, New Delhi; Swarajya Magazine, Bangalore; Foundation Institute for Eastern Studies, Warsaw; Research Institute for European and American Studies, Greece, among others.

As well as having contributed for a research paper for the US Air Force, he has been cited by leading organisations, including the US Army War College, Pennsylvania; US Naval PG School, California; Johns Hopkins SAIS, Washington DC; Centre for Air Power Studies, New Delhi; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington DC; Rutgers University, New Jersey; Institute of International and Strategic Relations, Paris; Institute for Strategic, Political, Security and Economic Consultancy, Berlin; Siberian Federal University, Krasnoyarsk; Institute for Defense Analyses, Virginia; International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, Washington DC; Stimson Centre, Washington DC; Foreign Policy Research Institute, Philadelphia; Center for Strategic & International Studies, Washington DC; and BBC.

His articles have been quoted extensively by national and international defence journals and in books on diplomacy, counter terrorism, warfare, and development of the global south.