Diwali is arguably one of the most prominent Hindu festivals across India with various associated stories that speak of its importance. Some believe this was the day Rama returned back to Ayodhya, others link it to the spiritual conversation between Yama and Nachiketa from the Katha Upanishad, while in areas like Braj of Western Uttar Pradesh, where Krishna is the most prominent deity, it is celebrated as the time when Krishna had vanquished Narakasura from Pragjyotisha kingdom. Another story goes that it was during these 5 days of Diwali that Goddess Lakshmi, the consort of Vishnu, was born from the churning of the ocean at an ancient era. For some communities, the Pratipada day after the Kartika amāvāsyā is celebrated as the beginning of a new year. Generally, today, almost whole of India celebrates Diwali through worship of Lakshmi and Ganesha to usher in prosperity and remove obstacles for the coming year.

Except, in Tantra marga of KālīKulā, where this amāvāsyā is the most important night of the year for the worship of Goddess Kālī. In fact, so important that the authoritative Devi Mahātyam in a stuti describes this new-moon as kāláratri, while equating the Goddess with four most important, and powerful nights in the year – kāláratrir mahāratrir moha ratrisca dārunā.

Lineage of Kālī

From the knitted brows of her forehead’s surface immediately came forth Kālī, with her dreadful face, carrying sword and noose. She carried a strange skull-topped staff, and wore a garland of human heads. She was shrouded in a tiger skin, and looked utterly gruesome with her emaciated skin. Her widely gaping mouth, terrifying with its lolling tongue, with sunken, reddened eyes and a mouth that filled the directions with roars. She fell upon the great Asuras in that army, slaying them immediately. She then devoured the forces of the enemies of the gods. Attacking both the front and rear guard, having seized the elephants. Together with their riders and bells, she hurled them into her mouth with a single hand. Likewise, having flung the cavalry with its horses and the chariots with their charioteers into her mouth, she brutally pulverized them with her teeth. She seized one by the hair, and another by the throat. Having attacked one with her foot, she crushed another against her breast. The weapons and missiles that were hurled by the demons. She seized with her mouth, and crunched them to bits with her teeth. The army of all those mighty and distinguished demons. She destroyed: she devoured some, and thrashed the others. Some were sliced by her sword, others pounded with her skull-topped staff. [From the Devi mahātyam, 7th chapter. Translation by Coburn]

Kālī is one goddess, who has always evoked a strange mixture of divinity and terror, especially among those uninitiated or unaccustomed to her peculiar ways. However, for the Hindu seers, who were not conditioned to look at Reality in only its sweet and joyous aspects, but also the terrifying and destructive forms, Kālī is both a ferocious destroyer of asuric forces, and a mother to those who worship her. Historically, one particular categorization of the Śakta-s was based on geography, wherein the North-Eastern portion was known as Vishnukranta, and this is where the worship of Kālī reached highest prominence.

KālīKulā or the lineage of Kālī, as it is more commonly known by its followers, is a complex blend of philosophy and ritual with Kālī residing at the fulcrum of the path and auxiliary deities considered as emanations of Kālī. Noted Indologist N. Bhattacharyya writes, “The followers of KālīKulā are exclusively monists. They hold Shakti as the same as Brahman in its three aspects of sat (reality), chit (consciousness) and ananda (bliss), and not its māyāvivarta or transformatory aspect.”

Scholars believe that the earliest texts pertaining to KaliKula may have been lost. KaliKula was in inception related to the Uttarāmnāya categorization of paths, created from the superstructure of atimarga–Kāpālika practices as a sixth and more powerful transmission beyond the five sources of Saiva traditions. In certain old texts of this school, we find mentions of a goddess named Kālasamkarsinī, who is believed to have transformed into Kali at a later period. Perhaps, the oldest manuscript on Kali worship preserved today is the Yonigahvara [Hindu Tantric and Śākta Literature, Goudriaan, Teun and Sanjukta Gupta] dated approximately at 1200 AD. It forms a part of a larger text on Chandabhairava, which emerged from the ancient Shaktipīṭha of Oḍḍiyāna. The setting of the contents is in the cremation ground of Oḍḍiyāna, where Bhairava, surrounded by yoginī-s, speaking to his consort describes Kālī as: “beyond the senses, inconceivable, of free volition, free from defects, identical with the stainless supreme sky, free from desires, residing in the sphere beyond the firmament.” It then speaks of the lineage of guru-s who were adept in this vidya, and mentions Mīnanātha as the chief exponent of this yuga. Beyond the rituals and procedures associated with this path, it also mentions the various divisions, bheda-s of Kālī, and how they eventually merge into the rare and powerful, or transcendental, form of gúhya-kālī.

The Tantric initiate, who sought to follow the path of the KālīKulā basically aimed at incinerating his limitations or pāśa-s through a combination of unpredictable, terror-inducing, heterodox and intensely transgressive rituals executed with the attitude of a hero – vīrabhāva. The term vīra here needs more elucidation. While vīra normally means brave, in Tantric literature, it further denotes the second of the three categories into which all sādhaka-s are differentiated, that is, one who has gone beyond the herd-mentality-driven life of a pāśu, and turned himself into a vīra, who courageously and willfully works out his own spiritual salvation against any odds that life may throw up, but has not yet reached the level of the divya or divine. Some read it as another subtle way of putting the caliber of a sādhaka into perspective. A pāśu is a gross literalist, who can only understand what his five senses allow him to, while the vīra is one whose intelligence has become more subtle and therefore is capable of accessing the ādhidaivika jagat or the astral world. The divya is beyond even this and has entered into the ādhyātmika jagat; he is in constant communion with the Brahman (here Shakti), therefore not bound by any rules, or, whatever s/he may do is a rule onto itself. While there are many severe restrictions mentioned for the pāśu – for example, he should not worship at night – the main corpus of the Tantric texts were designed to act as guides for the vīra sādhaka.

One of the most predominant features of the initial style of KālīKulā vīra sādhanas, followed even today, but in reduced volume, involved ritualized engagement with objects from a cremation ground and use of items prohibited in standard religious practice. The initiated vīra is supposed to mediate on Kālī, or one of her emanations, inside a śmaśāna on specific tithi-s like astami or chaturdasi or amāvāsyā, while consuming ritually consecrated alcohol known as kāraṇa, while being accompanied by his bhairavī or partner. In other instances, a group of sādhakas may form an occult circle of worship – cakrapūjā – in appropriate settings to harness a greater collective power of invoking Kālī. Naturally, such heterodoxy was deemed severely offensive to mainstream religious sensibilities and therefore, Śakta Tantra developed on the fringes of the society often keeping its practical secrets of sādhana and philosophy notoriously guarded from the masses. An oft repeated saying demonstrated the attitude adopted by the vīra-s:

Antah-Śaktah bahih-shaivah sabhayam vaishnava matah Nana-rupadharah Kaulah vicaranti mahitale. [At heart a Śakta, outwardly a Shaiva, in gatherings a Vaishnava, in thus many a guise the Kaula-s wander on earth.]

To the unaccustomed mind these may seem dangerously random acts of willful divergence from the mainstream, but it had its own logic and schema. Moreover, while a lot of leeway was allowed to the individual sādhaka of this path based on his own strengths and weaknesses, there was still a broad and sound overarching structure in place that guided the individual. For example, in practice, vīra sādhana-s had a krama or progression into realms of greater complexity that was adhered to by specific sampradayas. In one such krama, that was popular till the 19th century in a sampradaya centered around an ancient and famous Shaktipīṭha, required the sādhaka to first complete his vīra siddhi, that is, establish himself as a vīra . This would entail a series of cremation ground rituals designed to take the seeker beyond fear, shame and disgust. After the Guru ratified the vīra siddha, he would then go onto perform dakini sādhana. Dakini in Hindu Tantra is considered to be an extremely malevolent spirit, more dangerous than the regular bhūta and preta. The practice was considered so risky that the guru would often assign an uttarasādhaka – an accomplished Tantra sādhaka – to act as an aid and protector for the vīra. When the sādhaka would sit inside the ritual setting, in some desolate region away from locality, inside a forest or a cremation ground, on a mundāsana chanting appropriate mantras, the uttarasādhaka’s job was to maintain the kīlana – the protective circle – around the sādhaka and chant mantras for his protection. Old texts from Eastern and Northern India in local languages mention that this particular sādhana was so dangerous, not that the previous one was any lesser, but this seems particularly awe-inspiring even by old standards, that the slightest error or lack of nerves would leave the seeker mad or suicidal. No half way measures, no second chances. The author has witnessed the devastating effects that such methods can have on those, who are psychologically unfit, yet attempt these sādhanas out of false bravado, or over-estimation of ones capabilities. Given the extreme nature of this process, for every one individual who succeeded, there would be many, who were reduced to a complete wreck.

To the unaccustomed mind these may seem dangerously random acts of willful divergence from the mainstream, but it had its own logic and schema. Moreover, while a lot of leeway was allowed to the individual sādhaka of this path based on his own strengths and weaknesses, there was still a broad and sound overarching structure in place that guided the individual. For example, in practice, vīra sādhana-s had a krama or progression into realms of greater complexity that was adhered to by specific sampradayas. In one such krama, that was popular till the 19th century in a sampradaya centered around an ancient and famous Shaktipīṭha, required the sādhaka to first complete his vīra siddhi, that is, establish himself as a vīra . This would entail a series of cremation ground rituals designed to take the seeker beyond fear, shame and disgust. After the Guru ratified the vīra siddha, he would then go onto perform dakini sādhana. Dakini in Hindu Tantra is considered to be an extremely malevolent spirit, more dangerous than the regular bhūta and preta. The practice was considered so risky that the guru would often assign an uttarasādhaka – an accomplished Tantra sādhaka – to act as an aid and protector for the vīra. When the sādhaka would sit inside the ritual setting, in some desolate region away from locality, inside a forest or a cremation ground, on a mundāsana chanting appropriate mantras, the uttarasādhaka’s job was to maintain the kīlana – the protective circle – around the sādhaka and chant mantras for his protection. Old texts from Eastern and Northern India in local languages mention that this particular sādhana was so dangerous, not that the previous one was any lesser, but this seems particularly awe-inspiring even by old standards, that the slightest error or lack of nerves would leave the seeker mad or suicidal. No half way measures, no second chances. The author has witnessed the devastating effects that such methods can have on those, who are psychologically unfit, yet attempt these sādhanas out of false bravado, or over-estimation of ones capabilities. Given the extreme nature of this process, for every one individual who succeeded, there would be many, who were reduced to a complete wreck.

After this stage was accomplished, the sādhaka then moves onto worshiping a yoginī – one of the attendant female semi-divine deities surrounding the main goddess – who were famed for the supernatural abilities that they bestowed on the sādhaka. The specific yoginī to be appeased was based on various factors, including, but not limited to, the marital status of the sādhaka, because some of these beings are supposed to be so jealous and guarded that if invoked, they would sabotage all future attempts by the sādhaka to forge any relation with another woman or man as the case maybe, and even turn vindictive, if such was attempted. On the positive side, they could protect him from impending danger, warn him about real/hidden intentions of others, destroy his enemies, take care of his necessities, find out ancient treasures or reveal knowledge of rare sādhanas, and in some cases, even bestow occult abilities like turning invisible, levitating or being unaffected by elements.

When this too had been accomplished, THEN, and only then, the sādhaka, in this sādhanakrama, was considered fit to worship the Mahāvidya Kālī. It is important to note that as such anybody can worship a deity, it is however an entirely different matter for the worship to reach a level wherein the deity also responds to the call. Very few achieve this two-way communion. To make one capable of reaching that level of psychological fitness, and develop the necessary subtlety of mind and senses, such that the deity, in this case Kālī, responds, and one is able to understand the response, that this kind of a krama was designed for the initiated Tantra sādhakas of this sampradaya. For in the Shakta philosophy, worship without palpable results, based on unverifiable claims of next-worldly goodies or merely confirming to the tradition, is not enough. One must experience and then demonstrate that experience, or if so capable, transmit it to those, who may have the adhikara for it. Quite often, therefore, one finds that two sādhaka performing the same ritual will have nuanced variations, while following to a broad ritual superstructure. These nuances develop with time and practice, according to the specific needs and capabilities of every individual sādhaka. And this is where Vedic ritualism differs from Tantrica ritualism; in the former exact performance of the ritual is given primacy and the reward is metaphysical, the later places greater premium on results, which must be demonstrated immediately, or within a short time.

Diffusion of KālīKulā

करालवदनां घोरं मुक्तकेशीं चतुर्भुजं l कालिका दक्षिणां दिव्यां मुण्डमाला विभूषिता ll

सद्यछिन्नशीरा खड्ग वामदोर्ध्व कराम्बुजं l अभयंवरदं चैव दक्षिणोर्ध्वद पाणिकं ll

महामेघप्रभां श्यामां तथा चैव दिगम्बरीं l कंठावासक्त मुण्डाली गलद्रधीर चर्चिताम् ll

कर्णावतं सतानीत शवयुग्म भयानकं l घोरदंष्ट्राम करालस्याम् पीनोन्नत पयोधराम् ll

शवानं करसंघाती कृतकंची हसन्मुखी l सृक्कद्वया गलद्रक्त धाराविस्फ़ुरिटाननां ll

घोररावा महारौद्रिं शमशानालय वसिनिं l बालार्कमण्डलाकारं लोचनं त्रितयान्वितां ll

दनतुरं दक्षिणं व्यापि मुक्तलन्विक चोचयां l शवरुप महादेव हृदयोपरि संस्थितं ll

शिवाभिर्घोररावाभिश्चतुर्दिक्षु समन्वितां l महाकालेन च सामं विपरित रातातुरां ll

सुखप्रसन्न वदनां स्मेरनानना सरोरूहं l एवं संचिन्तयेत् काली धर्मकामार्थसिद्धिदा ll

Translation: Fearsome, with gaping mouth, freely flowing hair and four arms, the Divine Dakṣiṇā Kālī is adorned with a garland of heads, In Her left lower and upper hands She holds a freshly severed head and a sword. Her right upper and lower hands grant fearlessness and blessings. As magnificent as a huge cloud, dark, naked (clad in space), a garland of heads hangs from Her neck dripping blood from their severed edges. Corpses become Her earnings, a gaping mouth reveals fierce teeth, with full breasts; arms of corpses become Her girdle, with an illuminated face and blood trickling from her mouth; roaring fiercely, She is the great terrifier who dwells in the cremation ground. She is endowed with a third eye shaped like a circle resembling the newly risen sun; all pervading, unattached, She stands upon the heart of Mahadeva (Shiva) who lies like a corpse; Her auspicious and dreadful roars fill the four directions. Standing on top of Mahakala, united with Him; Her smiling face is pleasant and peaceful. Kālī, the granter of righteousness, enjoyment, wealth, and salvation, should be meditated upon in this way. [Dhyāna of Dakṣiṇā Kālī from Brihat Tantrasāra]

In what must have been an act of unmatchable cosmic irony considering the less than friendly equations that Śakta-s and vaishnava-s shared in medieval Bengal, the greatest Śakta mahāpaṇḍita and Tantric master from that era was born in the staunch vaishnava family of Advaita Acharya: closest companion of the iconic Caitanya Mahāprabhu. Known to the world as Kṛṣṇānanda Āgamavāgīśa, this legendary mahāsiddha authored the compendium called Brihat Tantrasara gathering information from nearly 150 authoritative texts and adding his own spiritual insights into them. The Tantrasara occupies a position of unquestionable supremacy as the single most authoritative manual of practical sādhana in the existing KālīKulā tradition.

Legend has it that Kṛṣṇānanda by the power of his sādhana, divined, and popularized the veneration and ritual methods pertaining to the worship and celebration of Daksina Kālīka, a form hitherto unknown in the universe of Kālī sādhaka-s. Perturbed by the fact that the actual siddhi in KālīKula entailed extremely dangerous methods fraught with danger such that only a select few can really succeed, the story goes that Kṛṣṇānanda performed a powerful sādhana and asked his Iṣṭa-devatā, Kālī, to manifest a form more suitable for this age. In a dream, he was instructed to meditate on the first thing he saw in the morning, which happened to be a dark woman with open hair, who was applying fresh cow-dung cakes on a wall early morning, a scene quite common in Indian villages. Seeing Kṛṣṇānanda, the lady supposedly stuck her tongue out as an involuntary gesture of being ashamed, as her hair was not tied in properly fashion. Using this as cue the Tantrika meditated further and came up with the iconography, mantra, yantra, nyāsa, theology and related sādhana paddhati of Dakṣiṇa Kālī, who is easily the most popular and ubiquitous form of the deity today.

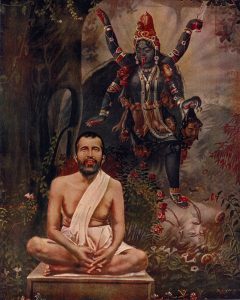

Dakṣiṇa in the context of Śakta Tantra refers to the right-hand path. Eventually, with the advent of many great Kālī-worshiping saints like Ramprasad and Ramakrshna, this Mahāvidyā transformed into a household deity across Eastern India where her motherly aspect grew in prominence compared to the terrifying ritual liturgy. Raja Krsnachandra of Navadwipa, himself a Tantra sādhaka and a contemporary of Ramprasad, is said to have popularized the worship of Kālī on Kartika amāvāsyā night. The puja is also known as nishi puja, because it starts at sunset and ends with the sunrise next day, which also happens to be a perfect analogy for the overall philosophy of this path, where the seeker starts from darkness of ignorance and then fights his way into the light of knowledge. It is believed that on this night the veil that separates the physical world from the astral is rendered thin, thus making it easier to access all kinds of occult forces and beings, both benevolent and malevolent. While a few use this night to establish contact with different types of spirits – yakṣiṇī, yoginī, bhuta, preta– the majority of sādhakas worship Kālī using a complete or partial Tantra-derived procedure involving stuti, stylized offering of various upacāras, bali, homa or a combination of these, where the goddess is considered the Supreme controller of the astral realms, mistress of all ethereal entities, and the ultimate guide, destination and bestower of siddhi.

To her sincere devotees, Kālī will remain a personification of ruthless force, and unstoppable might, who also inspires the seeker to transgress boundaries real or imagined, psychological or societal. Her worship is fit only for the bravest, for she won’t bat an eyelid when inflicting punishment onto an erring sādhaka; at the same time the intensity of her love overwhelms and protects the sādhaka from a million dangers in all the three realms of Reality that beset the long road to salvation.

O mind, repeat her name: Kālī, Kālī.

Why do you not repeat the name

Of her who destroys all danger?

Why do you forget?

Feel no fear of the vast ocean of existence,

For Kālī shall take you easily across this sea of life.

Do not fret, O mind: what is past is dead and gone.

Waste no time in vain pursuits,

But utter Kālī’s name without regret.

Casting dust into death’s eyes, cross the sea of life.

O mind, says Rāmprasād, why do you forget her?

Your time is coming to an end,

So repeat without end the name of Kālī.

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Svechchachari is the pen name of a tantrik sadhaka, who wishes to remain anonymous so that he is able to express his opinions and share his experiences more freely through his writings.