Belgian scholar Koenraad Elst’s Decolonising the Hindu Mind is a scholarly survey—and his doctoral thesis—that examined in depth just one question: the causes behind the astonishing rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party from just two seats in 1984 to 182 in 1998. Among other things, the book also takes a severely critical look at the BJP’s failures. One of the reasons Elst cites for the limited success of the BJP is the fact that the BJP (and its affiliates and ideology) “has always played the game according to the rules set by its opponent,” needless to say, the Congress.

One of the chief ingredients of that game as played by the Congress has been what I’d like to call socialist secularism. Even a cursory survey of the Indian political scenario since the ascent of Nehru shows that every party except the BJP is a clone of the Congress as far as minority appeasement and socialism are concerned. The BJP for all its Hindu/Hindutva espousal used to buckle down defensively at the Congress accusation that it was not secular. This among other things led the electorate to vote for the original than the clone, and was what had prevented it from crossing the 182 mark.

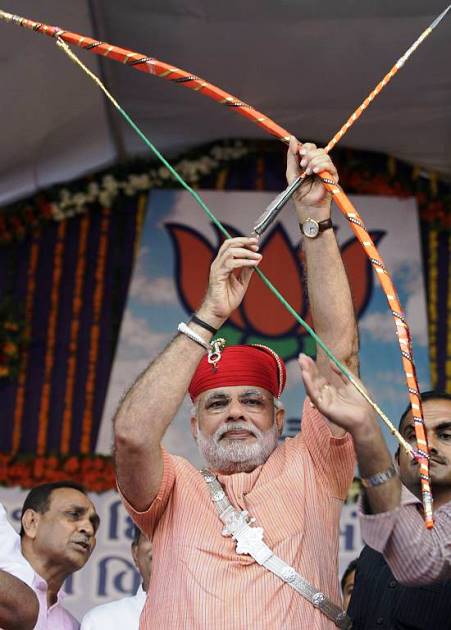

Now, with the polling for the 2014 elections already underway, and with almost all surveys giving a massive tally to the BJP it appears that things have fundamentally changed—perhaps for the long term—as at least two perceptive pieces indicate. And whatever one’s opinion about the man, it is doubtless that Narendra Modi has spearheaded this fundamental shift. Time will tell us whether this shift is for the good or otherwise.

One of the ways Narendra Modi has done this is by completely bypassing the aforementioned traditional way the electoral game was played. In other words, he has set the agenda and has forced his opponents to react. Indeed, it is very telling that the only plank on which the Congress has to ask voters to vote for it is “vote for me because my father and grandmother died for the country.”

And really, Modi’s agenda is simple: development, governance and security, which he has delivered in Gujarat for at least a decade.

And this agenda is completely alien to the Congress which had succeeded for over four decades, first through state-enforced policies of scarcity and spurious secularism. Simultaneously, it spawned an entire ecosystem of intellectuals, academics and media to perpetuate this sort of politics alive. Nothing else can explain the sort of spiteful appeal from a host of these notables in the Guardian to stop Narendra Modi at any cost.

It is no exaggeration to say that what is known as the Modi phenomenon has emerged from ordinary people cutting across party, caste, and community lines. Which also explains why almost every other party is making a beeline to ally with the BJP. Regional and caste chieftains who held on to their vote banks using narrow, identity-based planks are seeing their holds slipping away and are thus actively courting the BJP sensing this massive change in the wind.

Indeed, Modi’s adversaries best illustrate this. It is one thing that Modi’s political opponents are rattled but it speaks of wholly something else when non-political entities cutting across various professions both within India and abroad have combined forces to viciously attack one man using mostly foul means. What is especially noteworthy is the spate of distorted articles emanating from the Western media whose sole purpose seems to be to malign Narendra Modi. The latest is from Washington Post, which claims that the Godhra train burning occurred because Kar Sevaks fought with Muslims in the railway station! Indeed, the bizarre argument of the Modi naysayers appears that it is okay to overlook the gargantuan loot of the UPA not to mention its destruction of institutions—and vote it back to power—but it is mandatory to stop a person who the Supreme Court has exonerated on the very charge that these naysayers say is the sole reason to stop him.

And the chances of that happening are bleak as we saw.

The immense popularity of Narendra Modi can be described in what is known as “disruptive innovation” in the technology parlance. In recent memory, Email is a good example of disruptive innovation, which rendered post offices almost useless. So is the smartphone pioneered by Apple, which completely changed the way people used to regard mobile phones: it almost obliterated the need for using the phone’s physical hardware (numeric buttons).

In much the same way, Modi has outflanked the dominant political discourse. At the time of Independence, millions of Indians hadn’t even an iota of what democracy actually meant. The Constituent Assembly debates arguing against extending universal adult franchise are highly revealing in this context. However, the pro-universal adult franchise team won the day with the result that continues to haunt us: we tend to regard our elected representatives as rulers instead of as one of our own whose job is to govern us. It is therefore pertinent to ask the last time the Congress party even mentioned the word “govern.” From its 50 plus years at the helm, it’s clear that the omission of this word was calculated—to lull the people of India into accepting every excess including the Emergency and the 1984 Sikh pogrom, and still vote the Congress back to power.

As Arun Shourie and others have observed, the Manmohan Singh tenure is notable for two things: the absence of Government and the erosion of the authority of the Prime Minister. And this had to be the logical outcome. The Congress really had no leader worthy of the office of the Prime Minister after the demise of P.V. Narasimha Rao. And so, it had to appoint one in 2004.

In light of this, what Modi’s repeated emphasis on “good governance” and his record of delivering on it signifies is clear. It is this emphasis on good governance that the fundamental shift and the disruption refer to.

Sandeep Balakrishna is a columnist and author of Tipu Sultan: the Tyrant of Mysore. He has translated S.L. Bhyrappa’s “Aavarana: the Veil” from Kannada to English.