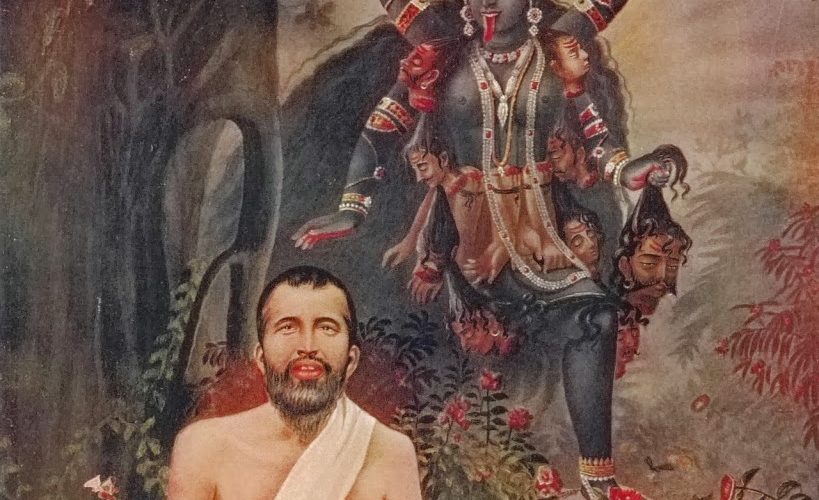

In his Soundaryalahari Verse 22, Sri Shankaracharya submits a very unique prayer to Goddess Bhavani. He says:

भवानि त्वं दासे मयि वितर दृष्टिं सकरुणां

इति स्तोतुं वाञ्छन् कथयति भवानि त्वमिति यः ।

तदैव त्वं तस्मै दिशसि निजसायुज्य–पदवीं

“O Bhavani, you, on this your servant, bestow a kind look”

Thus intending to adore, no sooner one begins saying: “O Bhavani, you..”,

You grant him that state of identity with you.”

According to the hymn, while Shankaracharya (here after refereed as Acharya) started his hymn in praise of the Goddess with the intention of requesting Bhavani to grant her grace on him, who is her humble servant; the Goddess in her eagerness to bless her devotees did not wait for the Acharya to even complete the prayer. Instead, as soon as the Acharya uttered “भवानि त्वं” or “O Bhavani, you”, considering the phrase itself as a full prayer, She granted him Sayujya or the ultimate unity and identity with the Goddess.

The hymn is unique not only because of its richness in the use of poetic devices, but also because, by using wordplay, the Acharya conveys a deeper teaching on Bhakti. In fact, the Acharya sheds light on the entire gamut of mature Bhakti, with its beginning and the end. “भवानि त्वं– O Bhavani, you” are the two terms that Acharya has chosen for this purpose. In the first line of the verse, भवानि त्वं is used in the sense of addressing the Divine mother with a prayer “O Bhavani, you bestow a kind look on this servant”, indicating the status of duality between the devotee and the deity as the starting point of Bhakti. But, in line two and three, the Acharya beautifully suggests that instead of understanding the address at face value, the Goddess in her compassion interpreted भवानि त्वं as भवानित्वम् i.e. the state of being Bhavani*, and hence, interpreting the prayer as “Bhavani, (grant me the state of) You”, She granted Sayujya or unity with Her, indicating non-duality or unity of the devotee with the deity as the end goal of Bhakti. This was later used by stalwarts like Madhusudhana Saraswati (MS) to develop a full-fledged theory of Bhakti yoga from the standpoint of Advaita Vedanta.

To appreciate what is being stated here, let us turn to Gudhartha Dipika, the commentary on Bhagavad Gita written by MS. In his commentary to verse 18.66, Madhusudhana Saraswati writes: “With the maturity of spiritual practice, three types of surrender to God come about- ‘I belong to him indeed’, ‘He belongs to me indeed’ and ‘I am He indeed’. These are the three stages of Bhakti through which a devotee invariably goes through as his Bhakti matures more and more.

In what can be considered the first stage of mature Bhakti, the devotee holds onto the notion that Ishwara is of infinite glory, while Jiva or individual is limited. Ishwara is the whole, Jiva the part. Jiva is invariably dependent on Ishwara. The notion is “I belong to Him and not the other way”. The Acharya expresses this as the beginning point of a mature Bhakti, by phrasing his prayer itself as a prayer to Goddess to “bestow her kind looks on his servant”. MS calls such a Bhakti as “Preyo-Bhakti” characterized by the mood of master-servant relationship [Sevya-Sevaka Bhava]. The revered Acharya expresses such a notion of Bhakti in his Vishnu Satpadi (Verse 3) as well, where he says: “O Lord! Even though there is no difference between us (I am a part of You), I belong to You and not vice-versa. Just like the ocean is made of waves but the waves are not made up of ocean.” Again in his Shivanandalahari (Verse 61), the Acharya gives two examples for this kind of Bhakti: The seeds of Angola naturally being drawn back to the tree and the iron needle becoming drawn towards the magnet.

In the second stage, MS says that the devotee develops the notion that “He, the Ishwara belongs to me, the Jiva”. Here the Bhakti has matured so much that the Individual becomes rooted in the conviction that the Lord will never abandon him and that Lord truly belongs to him. In Shivanandalahari (Verse 61), the Acharya again gives two examples of this kind of Bhakti: the virtuous wife who is fully devoted to the husband and the creeper which takes support in the tree. Just like a wife who considers the husband as belonging only to her or a creeper which fully relies on the tree for its support, the devotee becomes fully dependent on Ishwara and at the same time, perceiving Ishwara as specially belonging to him. In Krishna Karnamrutam (3.96), Bilvamangala Swami expresses this notion of Bhakti, when he says: “O Krishna, how strange it is that You are going away by forcibly flinging aside my arms! I shall consider it manly, if you can go away from my heart.”

In the third & final stage, the devotee will become established in the notion “I am He indeed”. This is the culmination of Bhakti in Sayujya or Unity & identity of the devotee with his object of devotion i.e. Ishwara. It is the ultimate expression of what Sage Narada calls “Viraha Bhakti” or Bhakti experienced in the form of pain of separation, which leads the devotee to hanker for complete unity with Ishwara, ultimately culminating in such a unity in the form of Sayujya born out of Knowledge in the form of “I am He indeed.” Vishnu Purana (3.7.32) gives an example for this kind of Bhakti, in the form of instruction from Yama to his messenger: “Those who, with regard to the infinite One who has entered the heart have the firm conviction, ‘All this and myself are Vasudeva; that supreme Person, the Supreme Lord, is one’, — go away leaving them at a distance.” Kapila Gita, which appears in Srimad Bhagavatham calls this kind of Bhakti as “Nirguna Bhakti”, which it describes as the bhakti of the highest kind, wherein “one gets addicted with devotion that does not see any distinction, without any expectation of results, to the Purushhottama, who lives in the deepest hearts of all, like the waters of the Ganges that keeps on going to the ocean.”

It is this culmination of Bhakti that the Acharya says the Goddess Bhavani was eager to grant him, even though he only intended to ask for her grace as a servant. Like Kapila Gita, Acharya also illustrates this stage of Bhakti in his Shivanandalahari (verse 61), with the example of rivers which continuously flows towards and eventually becomes united with the Ocean.

Thus, in a single verse, the Acharya expounds how Bhakti which begins with the notion of duality between the devotee and the object of devotion exemplified by the statement “भवानि त्वं दासे मयि वितर दृष्टिं सकरुणां– O Bhavani, you, on this your servant, bestow a kind look”, ends with the unity of the devotee, the object of devotion and the devotion itself as illustrated by the third line “तदैव त्वं तस्मै दिशसि निजसायुज्य–पदवीं- You grant him that state of identity with you”. Therefore, Bhakti is both the means and the goal of all life. As MS rightly notes in his Bhagavad-Bhakti Rasayana, Bhakti is the “Parama-Purushartha” or the Ultimate goal of life.

* I would like to express my gratitude to Acharya V S

Bibliography:

Bhagavad-Bhakti-Rasayana of Madhusudhana Saraswati

Bhakti Sutras of Sage Narada

Gudhartha Dipika of Madhusudhana Saraswati

Krishna Karnamrutam of Bilvamangala Swami

Shivanandalahari of Adi Shankaracharya

Soundaryalahari of Adi Shankaracharya

Srimad Bhagavatham of Sage Vyasa

Vishnu Purana

Vishnu Satpadi of Adi Shankaracharya

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Nithin Sridhar has a degree in Civil Engineering, and having worked in the construction field, he passionately writes about various issues from development, politics, and social issues, to religion, spirituality, and ecology. He is currently Editor of IndiaFacts- a portal on Indian history and culture; He is editor of Advaita Academy dedicated to the dissemination of Advaita Vedanta. He is a Consulting Editor to Indic Today Magazine. He is based in Mysuru, Karnataka. His first book “Musings On Hinduism” provided an overview of various aspects of Hindu philosophy and society. His latest book ‘Samanya Dharma’ enunciates upon general tenets of ethics as available in Hindu texts. However, his most widely read book is “Menstruation Across Cultures: A Historical Perspective” that examines menstruation notions and practices prevalent in different cultures & religions from across the world. He tweets at @nkgrock.