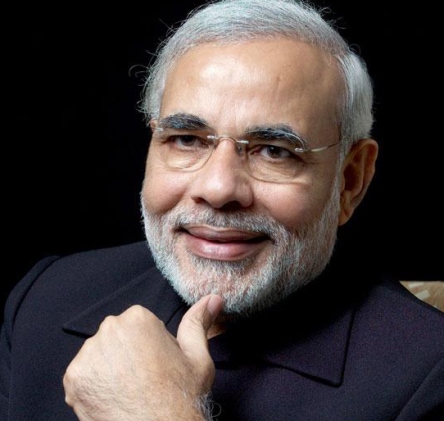

In its 14 December 2013 article on Narendra Modi, the Economist makes several assertions about the Gujarat riots of 2002. Most of these assertions are focussed on how Narendra Modi did nothing to prevent and/or check the riots.

Mr Modi could have forbidden the bandh; he could have quickly ordered a curfew; he could have compelled the police to act. He did none of those things. Nor did he call in the national police force or the army soon enough. India’s human-rights commission described the response by the state government as a “comprehensive failure”…Some say he was more directly culpable, alleging that he deliberately stood down the police.

The Economist is neither the first nor the last media outlet to have a penchant for dragging Modi’s supposed culpability in the Gujarat riots. So, it’s good to revisit the facts.

A handpicked Special Investigation Team (SIT) of India’s Supreme Court absolved Narendra Modi of any complicity in Gujarat’s widespread communal riots in February 2002. It also denounced his most persistent accuser, Teesta Setalvad who has strong ties to India’s ruling party, of lying. But then it is India’s Supreme Court and, one presumes, it should not to be taken seriously by any sane European.

Narendra Modi had been chief minister of Gujarat for barely a few months when the riots occurred and the police were overwhelmed by their scale. Its unlikely he could could have done anything more than he did though it points to inadequate policing across India. In other words, the phenomenon of not having an effective police force is not unique to Gujarat. This is borne out when one examines the historical data available for various communal riots in different parts of India.

Shoot-on-sight orders were issued at 5 pm on the day the riots began and thousands of Hindus (yes!) were arrested. Modi subsequently fell out with the leadership of the Hindu group condemned for being at the forefront of the protests following the torching alive of 59 Hindu pilgrims, which sparked the rioting. This is one of the rare occasions of rioting when the police shot so many Hindu rioters. The chief minister has been subjected to relentless scrutiny ever since, for reasons that have something to do with political rivalry.

And, yes, Narendra Modi has apologised, for what it was worth, once the harm had been done. So why the blatant misinformation by the Economist? The rehabilitation of riots victims also involved major Muslim organisations and that is on record.

Many more serious riots in India have passed with little comment, the worst being the officially-sponsored mass murder of Sikhs in Delhi after the assassination of Mrs Indira Gandhi. The man who subsequently became Prime Minister, her son, Rajiv Gandhi, virtually gave public approval to the retaliatory killings.

In fact, the disinformation about the Gujarat riots which the Economist repeats is cited by Islamic terrorists after every outrage in India. Authors Adrian Levy and Cathey Scott-Clark, in The Siege, point to the catalysing role allegations about the Gujarat religious riots played in motivating the terrorists who attacked Mumbai, killing many British visitors as well as others.

One wonders if the Economist would be prepared to make similar criticisms of China, Saudi Arabia or indeed Pakistan for egregious violence rife in these countries? As for the Economist’s lazy accusation that Narendra Modi is dictatorial, so unlike China’s leaders, it is laughably false. If anything, Modi keeps getting democratically elected by the same people of Gujarat he has allegedly governed in dictatorial style as per the Economist’s assessment!

All the information above can be verified in the Indian feminist and erstwhile critic of Modi, Madhu Ksihwar’s accounts, available on the Internet.

Dr. Gautam Sen taught international political economy at the London School of Economics and Political Science for over two decades.