The Universe can be thought of consisting of essentially two things; the subject I and the object, the world. The subject cannot become an object and vice versa. I am a conscious entity and the world is an inert entity.

In fact, I am the only subject in the world, and from my reference point everything else becomes an object that can be known through a pramANa or means of knowledge. From your reference, you are the only subject and everything else is an object of knowledge.

We need to examine the tools available to analyze the subject, I, and the object, this, and their limitations as means of knowledge. Science, as we know, deals with the world of objects or objectifiable entities. We are in the era of science, and have been brought up with the mentality that only facts verifiable by scientific methods are valid science, while the rest are subjective and can be dismissed as beliefs or dogmas.

We need to examine the validity of this statement scientifically. We will establish that Vedanta is an absolute science while all other so-called object sciences are only relatively real.

The word science is derived from the root ‘scier’, meaning to know. Hence science really means knowledge which reveals a fact or truth. In Sanskrit, ‘vid’ means to know, and ‘veda’ means knowledge.

Combining these two statements we can say that Veda means science.Vedanta means that which reveals the ultimate knowledge or absolute truth. From this, it follows that Vedanta is the ultimate science.

This is not a fanatical statement but a statement of fact, as in ‘Light travels at 299,792,458 m / s’. This is not an opinion or belief but just plain fact, whether one believes it or not. We will examine here why Vedanta is the science of absolute.

Epistemologically, the word ‘knowledge’ without a qualifier, cannot be defined. The qualifier objectifies the knowledge as in knowledge of Chemistry or knowledge of Physics, etc. It is always knowledge of something.

It can be knowledge of physical or phenomenal world, or knowledge of some subtle entity such as emotions, thoughts, intellectual concepts, etc. The former can be considered as the knowledge of gross entities that can be known via sense input, while the later can be called the knowledge of subtle entities and can be known without the need of any sense input, or can be inferred indirectly from the sense input.

For example, I can have knowledge of a force, which is subtle, when work is being done. Any action involves a force. We know that there is a life-force (prana-Shakti) by the expression of life activities. What exactly is life, even doctors cannot define it as it is imperceptible; but yet they can certify whether one is alive or not by examining life’s grosser expressions.

In essence, from action we can deduce the driving force for that action. A change of state, for example, involves a driving force, even though the force itself is imperceptible. Hence Vedanta says one becoming many involves a driving force, which it calls as maya-shakti or force of maya. The point here is that all forces can be inferred from the change of state, although they are imperceptible.

Pure knowledge without any objectification cannot be defined. In fact, any definition involves objectification. Conversely, only objectifiable entities can be defined. Vedanta says all objectifiable entities are inert or conversely only inert things can be objectified. Hence all knowledge that we are familiar with are knowledge of objectifiable entities, and therefore knowledge of qualifiable entities or of inert entities.

Science,in common parlance, means only knowledge of objectifiable entities, or inert entities, either gross or subtle. For example, Physics, Chemistry, Astronomy, Biology, Medicine, etc., all pertain to objectifiable sciences or sciences of grosser entities that are measureable or quantifiable by sense input data using objective tools.

Even when we are examining or quantifying living beings using objective tools we are only examining either body parts which by themselves are inert,or activities at grosser level to deduce that they are living beings.

Subtler sciences such as Psychology, Philosophy, Logic, etc., are not amenable directly by sense input, and therefore are not ascertainable or quantifiable by objective tools. One can infer to some extent by the behavioral trends but they remain somewhat speculative and not assertive.

Kurt Gödel

A philosophy or even logic can be built based on axiomatic statements. For those who are familiar, there is the famous Gödel’s incompleteness theory for axiomatic systems. It states that all mathematical systems are axiomatic, and although self-consistent,they remain incomplete and therefore cannot be proven. Vedanta says pure knowledge is infinite and therefore cannot be defined. Even the word infinite is only a negation of its finiteness.

There are many infinities that we are familiar with during our studies. For example we say two parallel lines meet at infinity. This is one-dimensional infinity since they are separated by a finite distance. Another example is, we say the pi has infinite series, but has finite value.

Thus, these are finite infinities which in a way being defined. The absolute infinity which Vedanta calls Brahman cannot also be defined. Vedanta states that pure knowledge which we said cannot be defined is Brahman- satyamjnaanamanantam, brahma.

Analysis of How knowledge Takes Place

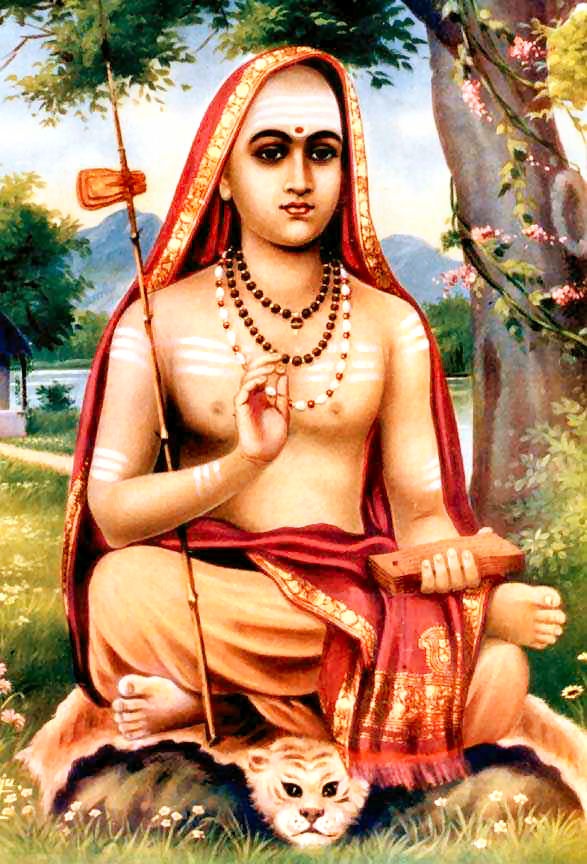

Adi Shankaracharya

In the knowledge of every object,three aspects are involved;a) the subject knower, b) the object known, and c) the means of knowledge that connects the two. These, in Sanskrit, are called pramaata, prameyam and pramaana, respectively.

Pramaata means knowledge and knowledge that is falsified later by a better or stronger pramaana is called bhrama or false knowledge. Thus, using pramaana, a pramaata can know a prameyam.

Let us take a simple example – I want to know if there is chair in the hall. To gain that knowledge, I need to go and see. I, the conscious entity, is the knower or pramaata, the chair is the object of my knowledge, prameyam, and the means of knowing or pramaana is perception that involves the sense of sight.

For the pramaana to operate my eyes should be functioning, and my mind should also be present,in addition to any other secondary requirements such as sufficient light in the room, for me to see.If the room is pitch-dark, I would not know if there is a chair or not, since I cannot see anything. Then, the existence of the chair in the pitch dark room is indeterminate, that is, it may be there or it may not be there. In fact, the probability that the chair exists or not is 50%.

The uncertainty, here, is due to the inability for the pramaana (sense of sight) to operate. Thus objective knowledge can be established only if all the three, the knower, known and the means of knowledge, are operating.Without the knower and the means of knowing, the existence of the object cannot be established.

Hence Vedanta ascertains that existence of an object is established by the knowledge of its existence, which requires a pramaata or a conscious entity. If I or no other conscious entity is present in that room to ascertain the existence of the chair in that room via direct or remote instruments of perception, the existence of the chair or any other object remains uncertain, with only 50% probability. It may or may not exist.

Suppose there is some other person (conscious entity) establishes existence of the chair in the room. From my point, the existence of a chair still remains as indeterminate unless he tells me the fact. Even then, my knowledge is not based on direct perception but on the validity of his words, called loukika shabdapramaana. I can validate his words by directly seeing its presence or absence.

Thus from my reference, I become the only subject to establish the existence or non-existence of an object, that includes the other beings. I have to establish the other person’s existence first before I can even validate his perceptual observation.

Thus, the fundamental requirement even for objective sciences that involve only objectifiable entities that use objective tools is that there must be a conscious entity to make the knowledge assertive or in technical jargon to make it deterministic than just probabilistic.

Erwin Schrödinger

In the above example, the existence of the chair in the hall cannot be established until I establish by a pramaana or means of knowledge. Until then, the existence of a chair remains as 50% probability. In Sanskrit, the word for indeterminacy is anirvacaniiyam. There is a famous example of Schrodinger’s cat problem that one can find in Google that proves the above fact that without consciousness ascertaining the existence of an object, the existence of the object remains only as probabilistic and not deterministic.

Suppose I ask,while you are in the pitch dark room, is there a gaabaabuubu in that room? You cannot answer that question even if the room is lit. You will first ask, what is gaagaabuubu or how does it look like, or what are its attributes?

Name or naama and attributes (starting with ruupa or form, etc.) go together in defining an object. If I do not know what is gaagaabuubu I cannot say it exists or does not exist. Naming involves knowing; and without the knowledge, existence of any particular object cannot be established.

When I see a new object for the first time, I will have knowledge of the existence of an object with some attributes that my senses measure. I may not know what it is if I have not seen any object with similar attributes in the past. When my teacher tell me that this is gaagaabuubu, now I have the knowledge of gaagaabuubu with name and attributive content stored in my memory. I can recognize the object later if I see any object with similar attributes. Thus cognition and recognition from memory go together, in the knowledge of an object.

In addition, even if the conscious entity or pramaata is present, the knowledge of existence of the object cannot take place unless the pramaana or means of knowledge operates.

In the above example, if my sense of sight is not operating or if mind is elsewhere, then I still would not know whether the chair is there or not, even when the room is lighted. For example, in the deep sleep state, the existence of any object, nay the whole world is indeterminate or anirvacaniiyam, since the instruments of perception, the senses and the mind, are folded or essentially not functioning.

Thus, even though I am there and objects may be there, there is no knowledge of their existence. The objects here include the grosser objects like room, bed and my body, etc.,but also the subtler objects like mind and the thoughts. Hence, without the mind present, no knowledge of the objective world takes place.

Therefore to summarize, any knowledge or science involves the subject I, the object this, and the connection between the two via a pramaana or means of knowledge. All three must be present for science to operate.

Analysis of Objective Sciences

An objective scientist provides a narrow definition for science as that which pertains only to the objectifiable entities using the objective tools. For example, he says that the existence of God cannot be scientifically established as His existence cannot be proved.

Obviously the proof that a scientist is looking for is perceptibility using objective tools of investigation, which themselves are limited to only objectifiable entities. He presumes that God is also an object that can be precisely defined to differentiate Him from the rest of the objects in the universe, and therefore quantifiable using perceptual data.If an object cannot be established by using his objective tools, then he ascertains that any assumption of its existence becomes blind belief or at the most speculative.

No object can establish its own existence since it is not a conscious entity. A chair does not say that I exist; a conscious entity has to establish its existence. A scientist, who dismisses the existence of God, since existence of God cannot be proved using his objective tools, takes his own existence for granted without questioning it.

He cannot establish his own existence or that he is a conscious entity using the same objective tools that he is using to validate the existence of God. The reason is he as a subject knower cannot be known since he cannot objectify the subject, knower. He knows that he exists and he is conscious entity, without even questioning the validity of his assertions.

The Universe

The definition of a subject is that which cannot be objectified. I cannot question my own existence, since the very questioning presupposes my existence. Object cannot become a subject, since only a conscious entity can be a subject. Subject cannot become an object since subject is a conscious entity and not inert entity.

Most importantly, from my reference, I am the only subject in this universe since everything I know or can be known are only objects. It includes all others both living and non-living things.

You may say thatyou exist and you are conscious entity. However, from my reference,your existence is established only when I hear you or see you or touch you, etc. Without the perceptual data I cannot establish your existence in the universe. You become another object of my perception.

Hence from each person’s reference point, he is the only subject in the universe and everything or everyone else is an object that either to be perceived or inferred. Thus, without the subject I, the object this, or person you, cannot be established as stated above by the statement that the existence of any object is established by the knowledge of its existence.

‘I’ cannot be known as object of knowledge since I am the subject; and at the same time I know I exist and I am conscious, without using any objective tools to establish my existence and my consciousness. For example, even in a pitch dark room, where I say I do not know the presence of any object, I know that I am there and I am conscious entity. I can negate or dismiss the whole world and even God for that matter, but I cannot negate myself since I have to be there to negate myself.

In addition, an objective scientist does not recognize the fact that if God exists he cannot be an object of perception, since one can only perceive finite objects. God, if He exists, cannot be finite since any finite entity gets limited by other finite entities; and any limited entity cannot be God, by definition.

Symbol of Infiniy

On the other hand, infinite is imperceptible and undefinable.

Even the word infinite is only negation of finiteness as attribute. God being a creator, as envisioned by all religions of the world,has to be a conscious-existent entity, since unconscious entity or non-existent entity cannot create.

If there is a God, and he being a creator, he cannot exist inside the creation or outside the creation either. To be outside the creation, that outside has to be created too. If that outside is also part of creation, then creation by definition has to be infinite.

Hence Vedanta says creation (referred to as idam) is infinite, poornam (puurnamadaHpuurnamidam). God cannot be inside the creation either since anything inside the creation has to be created. God cannot create himself, since he has to be pre-existing even to create himself, a logical contradiction.

Furthermore, the existence of Infinite conscious entity cannot be proved by using objective tools, which are limited. Hence the tools or the basis on which an objective scientist dismisses the presence or absence of God is invalid and therefore inadmissible.

In essence,the objective scientist is being very unscientific in his investigation of God, and therefore hisvery conclusion that the existence of God is more a belief than a fact itself has no basis. We are not proving the existence of God here, but only dismissing an objective scientist’s assertion that He does not exist because He is imperceptible.

In fact we can conclude that anything that is perceptible cannot be God; and if He exists, He has to be all-pervading or omnipresent, as all religions declare. In essence, objective sciences can neither prove nor disprove the existence of God, since the investigative means(pramaanas) are limited. They are valid only for limited objectifiable entities.

Limitation of Objective knowledge

There are several other limitations for objective knowledge. All objective knowledge is partial and not full since it involves only one of the three components involved in the knowing process;object, knower, and the means of knowledge.

By mutual exclusion, each limits the other. Hence any objective knowledge involves only transactional or working knowledge to facilitate transactions in the objective world, but cannot reveal the complete science or truth about the object under investigation.

Let us take the example of a chair. I say the chair is there because I see it; and as we discussed before, without my seeing it (or perceiving it via my senses) its existence is indeterminate. There are several other problems in considering that the chair is real because I see it.

First, what is seen is not really a chair but the light that falls on the chair which gets reflected by the chair and the reflected light reaches my retina forming an image of the chair, which is further transmitted by an electrical signal via optical nerves system to the brain. Perhaps a neuroscientist say further that these electrical signal forms neurons in the brain. This is the limit that the objective science can reach.

However, seeing involves the gross measurable electrical signal is further transformed into a subtle thought in the mind by some mysterious code that the scientist is unable to unravel using his objective tools. A thought (vritti) is not amenable for measurement by objective tools.

In the modern day, everybody is familiar with how a computer works using a programing language. The programing code converts the input from electrical signals into software that machine can understand.

Similarly God or say, nature has provided some intelligent programing code that transforms the electrical input from nerves system into thoughts that the mind can read or know. Brain is the hardware and mind and the thoughts are like software.

Objective sciences cannot establish even existence of a mind or a thought but we all know that we have a mind and we think. Philosophers and psychologists have analyzed the mind, each in their own way.

For example, whether the mind is matter or not is still a debatable question in science. Vedanta considers that mind is also a matter but is made up of subtle matter different from gross, just as software is different from hardware. Hardware is required to use the software.

Without the brain, mind cannot function but mind is different from brain. No objective tools can be used to quantify the thoughts and how one thought differs from other, since they are imperceptible. No scientist can say that existence of a thought is a belief or speculation, since he cannot prove its existence using his tools; even to deny or use his tools he has to think.

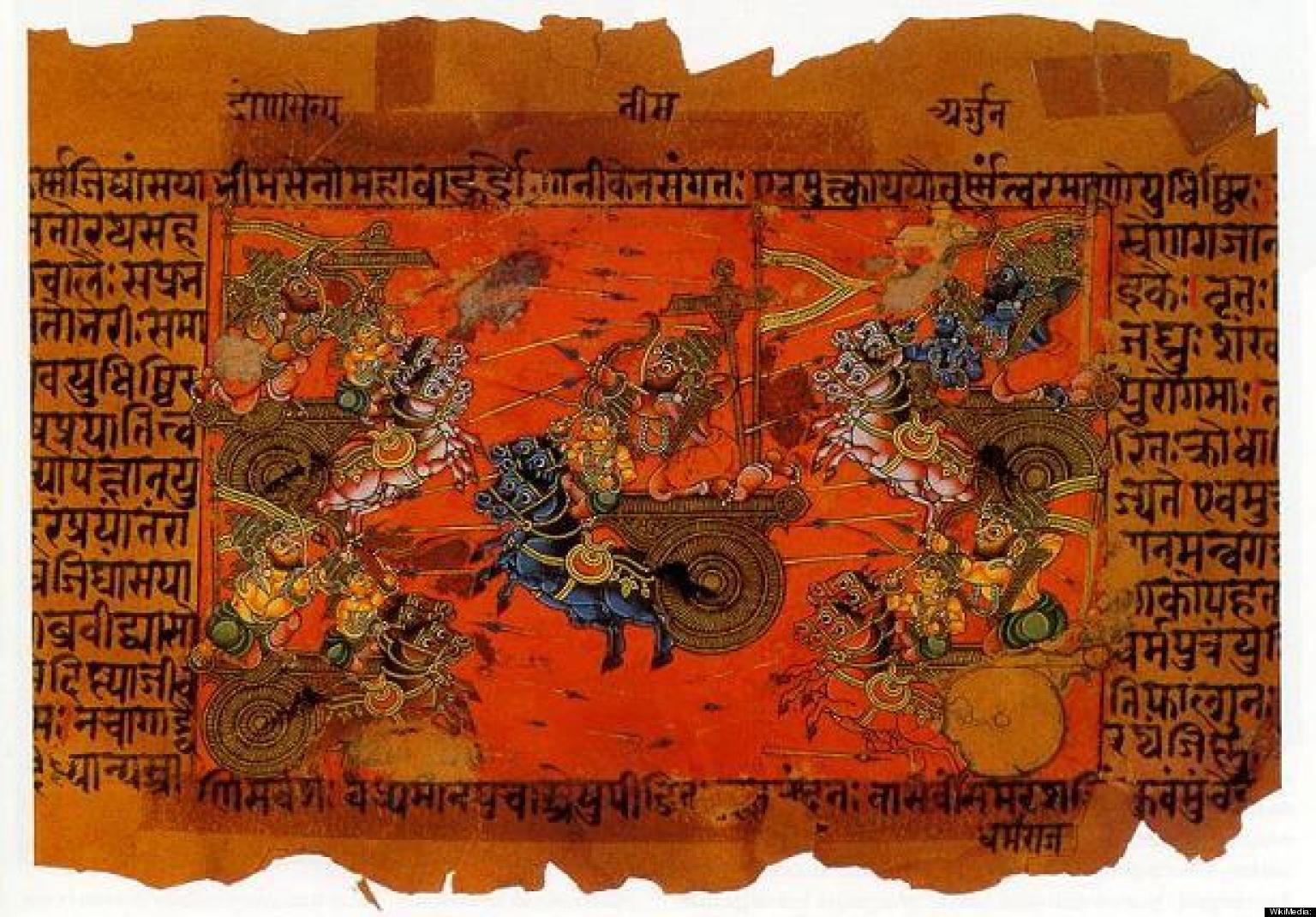

Bhagwata Gita

I cannot know your thoughts; I can know you are thinking when you communicate your thoughts by a common language. The western philosopher, Descartes, made the famous statement – I think therefore I am – while Vedanta says, I am therefore I can think, and I can also exist without thoughts as in deep-sleep state.

Coming back to our chair, the existence of a chair is ‘as though’ transformed as existence of a thought in my mind, which the conscious entity, I, the knower, using the mind, can see. Hence what I see is not really the chair out there, but its subtle impression in the mind as thought. The contents of the thought are nothing but the reflected attributes of the objects that I see.

In essence, I become conscious of the existence of the thought in my mind, and therefore conscious of the existence of a chair out there. (For more in depth analysis of perceptual process,see www.adviataforum.org, under ‘Critical Analysis of Vedanta Paribhasha’). Therefore, I do not really see a chair but only a reflected light from the chair. Similarly, I do not see any object without light illumining the object.

The same thing happens inside my mind; I do not see (recognize) a thought unless the light of consciousness that I am illumines the thought for me to be conscious of the thought, therefore conscious of the object out there.

Hence, it is not the object that I see directly, but only its reflected light from the object which forms the corresponding thought in my mind; and again it is not the thought that I see but reflected light of consciousness that I am. If I am color-blind then I cannot see the true colors of the chair.

In addition,that what I see is what is there (that it is not hallucination) can be ascertained only when I go and sit on the chair or transact with it; and that involves use of my organs of action (karmendriayas). Hence chair that I see is transactionally real only when I can transact with it.

Similarly the whole world that I see becomes a transactional reality (vyaavahaarika satyam) when both sense organs (jnaanedriyas) and karmendriyas (organs of action) ascertain its existence. Vedanta says transactional reality is not absolute reality.

What is Absolute Reality?

Vedanta defines the absolute reality as that which can never be negated at any time, trikaalaabhaaditamsatyam. As an example, let us analyze a chair made of wood.

Is that chair really real (styasyasatyam) or only transactionally real? When I dismantle the chair or break it into pieces, it is no more a chair. What was there before and what is there now is only wood. Hence wood is more real than chair.

Chair is only a name for a form of wood arranged in some fashion to serve some purpose, and gets negated when the form got destroyed. I can do this without breaking the chair into pieces. I can cognitively say that there is really no chair there but what is there is only wood currently in the form of a chair. Chair is only transactionally real but not really real; and what is more real than chair is wood, the material cause for the chair.

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad says every object is nothing but just a name for a form with some function (naama, ruupa and kriya); and it has no substantiality of its own.For example, if one looks at the wood carefully, it is just assemblage of organic fibers; and there is really no wood there.

Thus the chair is dismissed and wood is considered as more real and wood is dismissed and organic fibers are considered as more real. Organic fibers in turn are assemblage of molecules which are just the assemblage of atoms, which in turn are assemblage of electrons, protons and neutrons, etc.

At each level the name and form or naama-ruupa resolves into something else which is much more real than the previous state. The search for fundamental particles is still going on. In essence, we still do not know what chair really is as one form resolves into the next form.

Vedanta says there is no real material substantive for any object. However, in these investigations what remains non-negatable that seems to fulfill the definition of the absolutely real is that which is present all the time, and without which no investigation of any object is possible. That non-negatable one is the very inquirer, who is a conscious entity, without whom no investigation of reality can takes place.

Vedanta says I negate the whole waking world, when I go to dream state, and negate both waking and dream states, when I go to the deep-sleep state, and negate that state when I am awake. Each state negates the other.

However, I can negate each state but cannot negate my own presence in each state. The states can change but I remain changeless. I play the role of a waker in the waking state, dreamer in the dream state and deep-sleeper in the deep-sleep state. The roles that I play keep changing, but ‘I’remains the same, like an actor who is playing different roles in different scenes.

Vedanta says I am the only one in the universe who is absolutely real; where ‘I am’ should be understood as pure existent-conscious entity, and not the role that I play in each state. Thus each role is has relative reality in that state but I am the absolute reality independent of any state or experience in any state. I am the subject, conscious entity that cannot be objectified. Hence I cannot know myself as an object of my inquiry, since I am the subject in all objective knowledge.

The analysis of the perception discussed above shows that I am that light of consciousness that illumines every thought which is locus of the object that I perceive. In the waking state, the waking world of plurality forms the object of my knowledge, in the dream state the dream world of plurality form the object of my knowledge, and in the deep-sleep state the homogeneous absence of knower-known duality forms the object of my knowledge, which also expresses as absence of any suffering or as reflected happiness.

Recognition of Myself

While I play the role of waker in the waking state, and dreamer in the dream state and deep sleeper in the deep-sleep state, and I am neither a waker nor a dreamer nor deep sleeper since they are only roles in each state. Then who am I that is independent of the roles that I play?

This forms the fundamental inquiry and Vedanta says I am pure existence-consciousness, which is limitless, and which is pure happiness since any limitation cause unhappiness.

I can only experience the three states, waking, dream and deep-sleep states, where I am playing the roles of waker, dreamer and deep-sleeper. As long as I am in the BMI (body, mind, Intellect), I cannot but play the roles. I have to discover my true nature by negating the superficial roles that I am playing,while still playing, as neti, neti or not this and not this, since any this is only name, form and function; and thus arrive that I am pure existence-consciousness-limitless (sat-chit-ananda).

Logical analysis also indicates that the happiness that I am seeking comes from myself only. Yet, I mistake myself, with the limited body, mind and intellect,as I am this,in each state, and suffer the consequence of that identification.

Hence Vedanta, as a science of absolute truth, analyzes the fundamental human problem, and declares that by identifying myself with what I am not, I take myself to be mortal, ignorant and unhappy as I am. While Vedanta points out that being pure existence, I am eternal or unchanging; being consciousness I am pure knowledge (without qualifications) that we said is undefinable; and I am of the nature of pure happiness since I am infinite or limitless or full as I am.

In all human pursuits, I am trying to solve these three problems – I do not want to be mortal, I do not want to be ignorant and I do not want to be unhappy – which cannot be solved by any pursuits. At the same time I cannot give up the pursuits. All the rat-race is fundamentally to achieve these three.

In essence, I am trying to solve a problem where there is really no problem to start with, and that every effort to solve a problem-less problem has become a fundamental human problem. Only solution to this problem is to recognize that there is no problem to start with by claiming myself to be pure existence-consciousness-limitless or as Bri. Up says – aham brahmaasmi.

Hence Vedanta becomes absolute science of reality, since it reveals the absolute truth that transcends time and space. Hence, Adi Shankara says this in cryptic way,

brahmasatyam, jaganmithyaa, jiivobrahmaivanaaparaH|

anenavedyam tat shaastram, iti Vedanta dindimaH||

In essence he says that, a) the absolute reality is Brahman or infinite, b) the world is only transactionally real and not absolutely real and c) and I am that Brahman. That by which all these three can be known is the real science (tat shaastram) and this is what Vedanta declares.

Finally, Vedanta also says knowing this one knows, in essence, everything. On the other hand, in the relative knowledge or in any objective science, strange it may sound, the more one knows the more ignorant one becomes. The reason is obvious.

In the example of chair, we still trying to find out what chair really is; and this is true with any object in the universe. In any objective field of science, the more one inquires about the truth, the more it opens up with the result that I discover that what I know is very little compared to what I do not know.

My ignorance grows more than my knowledge. My area of specialization becomes narrower and narrower, the more I enquire into the nature of reality. Thus my ignorance of the subject grows faster than my knowledge. Every scientific paper ends with the statement that lot more study is required to understand the problem. That is the nature of all objective sciences.

On the other hand, in Vedanta, a student asks his teacher – Sir, please teach me that knowledge knowing which I will know everything – kasminnobhagavovijanaatesarvamidamvijnaatambhavati? The teacher is happy to teach that absolute science of Vedanta knowing which one feels that he knows the very essence of everything.

Hence Vedanta forms the absolute science, while all other objective sciences reveal only relative truths. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad says all objective sciences come under the umbrella of avidyaa or ignorance only,since the ignorance increases with knowledge in any given filed. These objective sciences however play an important role in the transactional world for ensuring proper transactions.

However, considering these relative sciences as absolute and the absolute science as belief system only reveals our ignorance.

Dr. Sadananda, a retired scientist by profession (US Naval Research Lab), is a disciple of Swami Chinmayananda, and one of the founding members of Chinmaya Mission Washington Regional Center. He has conducted several two-day Memorial Day spiritual camps at Chinmayam in the past: Upadesasara of Bhagavan Ramana, Dakshinamurthy stotram of Shankara, Advaita Makaranda of Lakshmidhara kavi, Mandukya aagama prakarana and Sadvidya of Chandogya. He has also conducted several Vedanta classes in Northern Virginia. He is currently teaching Gita Navaneetam classes at Durga Temple and conducting discourses on Taitereya Upanishad in Fairfax.

Dr. Sadananda was inducted into the Chinmaya Mission Acharya Fellowship by Swami Tejomayananda (Guruji) at the 16th Mahasamadhi Family Camp in Toronto (Jul-Aug 2009).

Acharya Sadananda can be reached at [email protected]