Appearing before Sanskrit mantras, or as a stand-alone entity, ॐ or OM is perhaps the most important sound, syllable, letter, and symbol in Hinduism. Whether in Hindu rituals, prayers, or Yogic activities, the ubiquitous nature of ॐ is a mystery to many. Its spiritual and philosophical significance in Hindu tradition is very vast, yet relatively unknown to many. In this article, I will attempt to approach the importance of ॐ from a purely scientific (linguistic) and philosophical perspective.

The Vedas and Vedangas

Derived from the verbal root ‘vid’, meaning ‘to know’, the Vedas are considered the most authentic source of knowledge in the Indian Intellectual Tradition. The Vedas, as shruti, are the most sacred, apauresheya (not created by humans) texts of the Hindus. According to the tradition, the rishis who ‘composed’ the hymns of the Vedas did not really compose/write those hymns, but they ‘heard/saw’, i.e. perceived them at some otherworldly plane and then expressed them in a human language. “The hymns were and are always there unchanging beyond our common world of change” (N. Kazanas). Hence, Vedas are also considered ‘nitya’, or eternal. It is to be noted that the word shabda in Indian Tradition refers to words, sound, and language itself. Vedas too have been called shabda both in the Purva and the Uttar Mimamsa traditions. Further, the Upanishads present the concept of shabda-brahman, the eternal sound. Since Brahman is nitya and apaurusheya, so is shabda, or the Vedas.

The vast Vedic literature includes the four Vedas. They are Rigveda, Samveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda. Each of them in-turn has four divisions: samhita, brahmana, aranyaka and upanishad. The Vedangas (literally, the ‘limbs of the Vedas’) are the ancillary disciplines, a prerequisite of sorts, for mastering/understanding of the Vedas. There are six in number and include shiksha (phonetics), kalpa (rituals), vyakarana (grammar), nirukta (etymology), chhanda (meter), and jyotish (astronomy). It is interesting to note that out of these six Vedangas, three (shiksha, vyakarana, and nirukta) are directly related to the field of linguistics. Hence, we can deduce that the understanding of the language, one way or the other, played a significant role in the understanding of the Vedas. Owing to its overarching position of eminence in the overall intellectual enterprise in ancient India, our ‘rishis’ and ‘acharyas’ delved deeply into the various aspects of language.

The Indian Intellectual Tradition and the Worldview

The Vedas consist of eternal words and the mantras out of which, it is believed, the entire universe can be created. A universe of objective realities exists, because humans can express it through language, Vedic scholars believe. Nothing exists without a language. Every element, every object, every idea in this world exists, because it can be expressed through a language. Rooted in this worldview, the Vedic mantras were recited by the priests at the altar during rituals and ceremonies to produce desired results, say, for example, rain. Since, the language was so central to the Vedic worldview, its purity, correct pronunciation, intonation, etc. was paramount in getting desired results. The necessity of ensuring that no corruption or modification should creep into the sacred Vedic texts (and the language itself) led Indian scholars to discuss, debate, and put forward theories of language, and discourse. To start with, there were fierce debates about the efficacy of the Vedic mantras itself. Yaska, the 5th century BCE etymologist, in his Nirukta mentions Kautsa (another grammarian), who believed that Vedic mantras were meaningless. To counter Kautsa, Yaska asserts that to get the meaning of the Vedic texts, one has to study ‘in the system’. Vedic texts cannot be studied in isolation. Besides the prerequisite of the six Vedangas, one must also understand the three basic concepts of the Vedas – (1) who the rishi (seer) is of the specific section (who perceived it and revealed to the world?). (2) to which devata the mantras are dedicated (for whom it is being said?), and (3) how is it set to meter or chhanda (how is it being said?).

The concept of sound, or shabda, in the Vedic tradition is central to the understanding of the principles of existence. Sound is considered to have three dimensions – the idea of an object, the presence of a speaker, and the subtle form of ether. Grammarian and philosopher Bhartrihari (late 5th century CE), in his Vakyapadiya, expounded the concept of shabdabrahman, the eternal sound. He postulates four stages of sound: (1) Vaikhari, as the spoken and written form, is the grossest level of speech. When a sound comes out of a speaker’s mouth, it is vaikhari. (2) Madhyama is the unexpressed, mental state of sound, but has most features of vaikhari. Hence, it’s called madhyama, the middle one. (3) Pashayanti, meaning that which can be seen or visualized, is the spiritual, undifferentiated stage. At this stage, the differences between languages do not exist. (4) Para, the fourth stage is the transcendent absolute stage and as such is beyond description. At this stage, the distinction between the sound and the object merge and the sound encompasses all the features and qualities of the object.

The Upanishads talk about the relationship between the words and the objects. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad talks about the unity of the words and the objects they signify. That is to say, the signifier and the signified are not physically distinct from each other. So, if the words don’t exist, so do the objects they signify. According to the Shatapatha Brahmana, the supreme consciousness Brahman enters into this world with rupa (form) and nama (name) and the world extends as far as the form and the name extend. Meaning, if form and name don’t exist, so does the world.

The Sanskrit Language

Sanskrit is one of the oldest, if not the oldest, languages of the world. It is the precursor of many of the modern Indian languages, including Hindi, Marathi, Bangla, etc. As we are aware by now, both the language and the science & philosophy of language have had an important place in the Indian Intellectual Tradition. As a result, it is but expected to have an extremely advanced tradition of intellectual inquiry in this field. I have already glanced through some of the philosophical discussions. In this section, we will look at the scientific aspect of the language.

Composed in eight chapters, and about 4,000 ‘sutras’, Panini’s Ashtadhyayi (4th century BCE) is considered one of the most complete grammars of any language. L. Bloomfield in his “Language” declares Ashtadhyayi as the “greatest monument of human intelligence”. For our purpose, we will restrict ourselves to the Sanskrit alphabets for now. Sanskrit alphabet is called varnamala, and the letters are called akshara. The akshara in the Sanskrit varnamala have a strict scientific organization. It is to be noted that akshara or “Without destruction” is called so, because sound is a form of energy and energy is never destroyed. It only changes form. Our rishis and acharyas were well aware of this property of sound and hence the name.

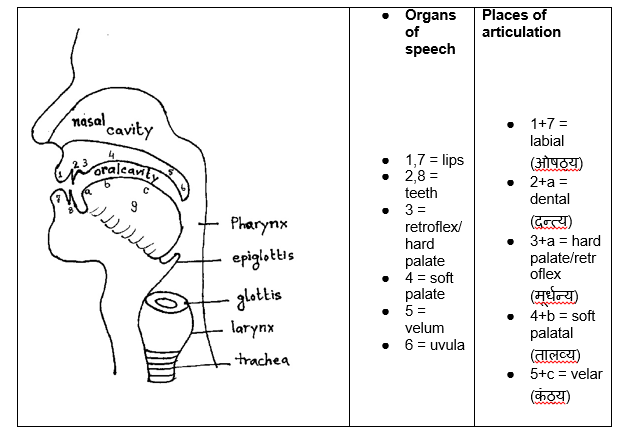

Back to Sanskrit alphabet, consonants (or vyanjana) of Sanskrit alphabet are grouped together based on, among other things, places of articulation. Each of this group is further organized into voiced/unvoiced (presence vs. absence of vibration in the vocal cords during pronunciation), aspirated/unaspirated (characterized by presence/absence of strong burst of breath), and nasal sounds (when sound is also allowed through the nasal cavity). For example, the first group of consonants, the ka-varg, has back of the mouth (velum or kanthya) as the articulation point. Similarly, ch-varg, has soft palate (talavya), T-varg hard palate (moordhanya), t-varg root of the teeth (dantya), and p-varg lips (oshthya). As one can easily notice, there is a natural progression in the organization of these consonants, viz. starting from the back of the mouth (throat) to the front (lips).

Figure 1: Places of Articulation

| Place of Articulation | Voiceless | Voiced | Nasal | ||

| Unaspirated | Aspirated | Unaspirated | Aspirated | ||

| Velarकंठ्य | क | ख | ग | घ | ङ |

| Palateतालव्य | च | छ | ज | झ | ञ |

| Retroflexमूर्धन्य | ट | ठ | ड | ढ | ण |

| Dentalदन्त्य | त | थ | द | ध | न |

| Labialओषठ्य | प | फ | ब | भ | म |

Figure 2: Sanskrit Consonant Groups

ॐ as Letter/Sound/Syllable

Om, represented by its symbol (the letter ॐ), is a combination of three sounds/letters – A, U, M (अ, उ, म). Om is considered the eternal sacred sound. It is the sound of creation and as such extremely powerful, infinite, and limitless. It is also considered the bridge between the inner and outer world. Om is Pranava, it is the root syllable (mool mantra) for all vaidik or tantric mantras. Om is the reflection of objective realities. It is both nama and rupa. Om exists on its own, without reference to anything else. Mandukya Upanishad declares Om as imperishable and everything (Om ityetadaksharam idam sarvam) and uses it to explain Brahman as the ultimate reality (“All this world is the syllable Om.”). Om is the past, the present, and the future plus whatever there is beyond this three-fold temporal classification.

As the ultimate reality, the Brahman, Om has four stages. The jagrata stage is the awake and alert stage that connects us to various external material bodies and objects. The second is the svapna stage. This is the stage of dreaming. This is the stage where the consciousness of a living body is overcome by unreal. In this stage of dreaming, one imagines the ‘dream’ (unreal) to be the reality and it has real physical as well as physiological effects on the individual. The third stage is sushupta. This is the stage of deep sleep, the stage of complete unawareness and inertness. One doesn’t know what is happening around him/her. This is a stage of objectless subject. The last stage of turiya is the transcendental stage. This is the stage of total bliss, the sat-chit-ananda, wherein the duality of subject and object ceases to exist. These four stages are manifested in the syllable Om (which is a symbol of Brahman). The Mandukya Upanishad describes the letters in Om in terms of above mentioned four stages (So’yam-atma adhyaksharam-omkaro dhimatram pada matra matrasca pada akara ukaro makara iti). The letter A, as the first letter of Om, is the representation of the jagrata stage. This sound is inherent in all other sounds. One who knows this sound has all desirable objects and is successful. Letter U represents the svapna stage. As an intermediary, it contains the qualities of both jagrata and sushupta stages. One who knows this sound, “knows the Brahman, the Absolute Reality”, declares the Mandukya Upanishad. The stage of sushupta is letter M. A knower of this can understand all within himself. The fourth turiya stage is the syllable Om itself – soundless and unutterable – hence the real true Self. One who knows this, experiences the Universal Consciousness.

Om can also be explained within Bhartrihari’s shabdbrahmana framework as well. The entire Universe is the omnipresent ever-expanding sound Om itself. It is as such a representation of the four stages of sound and their existential counterparts. The sound A at the grossest physical level is the vaikhari. Sound U, in the middle (madhyama) has qualities of both vaikhari and pashayanti. Sound M is the representation of the undifferentiated spiritual pashyanti state. Finally the syllable Om itself is the state of Absolute Consciousness, para. One can easily see the connection between the concept of shabdbrahmana and the four avasthas discussed in the previous paragraph. The jagrata avastha is the realm of vaikhari, svapna the realm of madhyama, sushupta the realm of pashyanti, and turiya the realm of para.

Om is also considered the essence of the Veda. According to the Katha Upanishad the goal of all Vedas is Om, which is indeed Brahman. “This syllable is the highest. Whoever knows this syllable attains all he desires”, declares the Katha Upanishad. In an article published in the New York Times (June 15, 1879), Max Muller writes: “Om is said to be the essence of the Sama-veda, which, being almost entirely taken from the Rig-veda, may itself be called the essence the Rig-veda. And more than that, the Rig-veda stands for all speech, the Sama-veda for all breath of life, so that Om may be conceived again as the symbol of all speech and all life. Om thus becomes the name not only of all our physical and mental powers, but especially of the living principle, the Prana or spirit … that none of the Vedas with their sacrifices and ceremonies could ever secure the salvation of the worshipper – i.e., that sacred works performed according to the rules of the Vedas are of no avail in the end, but that meditation on Om alone, or that knowledge of what is meant by Om alone, can procure true salvation or true immortality.”

Further, the symbol Om (ॐ) itself represents different levels of reality within which human beings operate. The lowest curve of the symbol is a representation of the jagrata state, the middle curve on the right hand side represents the svapna state, and the upper curve is the representation of the sushupta state. On top is a dot with a curve underneath, which separates the dot from the rest. The dot is the representation of the transcend order of reality that is one birthless infinite whole and hence beyond the grasp of the human mind. The entire symbol in itself is the representation of the state of samadhi. It encompasses in it the other three states and transcends them.

When one recites Om, he/she speaks the universal language. It is a language that encompasses within itself all the languages of the world. When we utter a sound/letter, say vowel A, a specific part of the human vocal organ is activated. When we recite Om, the entire vocal organ is activated. Om is a combination of three sounds/letters – a, u, m (अ, उ, म) – and together they represent the universal Brahman. While pronouncing अ, the most interior (back) part of the open, mouth is used. अ is also the first letter of the alphabet and is inherently present in all sounds produced by human speech organs. Next up, उ is pronounced from middle to front part. Finally, with the pronunciation of म sound, the most frontal part of our vocal organ (lips) is used, resulting finally in the closing of the vocal cord. It is also the last letter of the alphabet. As such, the pronunciation of ॐ is an invocation of the complete alphabet and hence perceptively all possible sounds. Hence, by pronouncing all three sounds अ, उ, म at once in the syllable ॐ, one is able to activate the entire spectrum of human vocal cord – from the back of the mouth to the middle and front. And to do this accurately, one must have a complete command over language. So, in a sense, when one pronounces ॐ, it signifies a speaker’s thorough command over language. And we know from our preceding discussion that those who have command over language are very powerful as the possibilities for them are boundless. By virtue of having command over language, one can now create/recreate the entire world, his/her own objective realities. That power is simply profound!

To conclude, in the words of Swami Krishnananda, “Om, therefore, is name and form; form and formless; vibration and consciousness; creation and satchidananda. All this is Om.”

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Avatans Kumar (@avatans) is a marketing, IT, and PR professional. Avatans holds graduate degrees in Linguistics from JNU and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and MBA from Webster University. Avatans has keen interest in topics involving Indian Intellectual Tradition, history, and current affairs.