The Mahabharata has lived for thousands of years for the reason that it serves as that vast ocean human emotions in which everyone can pour their own understanding and find acceptance without judgment.

There is an innate human desire to see and interpret things in a monochromatic palette of black-and-white. One could argue that stereotyping is an “energy-saving” device that allows us to make “efficient decisions on the basis of past experiences.” (“Stereotypes as energy-saving devices: A peek inside the cognitive toolbox”) . Therefore, is it any surprise that many of us look at the characters in the Mahabharata also through similar, stereotypical lenses? It simplifies things if we view Duryodhana as the jealous usurper, Shakuni as the manipulative uncle, Bhishma as the noble but helpless elder, Arjuna as the hero, Karna as the tragic and righteous hero fighting on the wrong side, and so on. No, it is not quite proper or kosher to include in this group of admirers (and critics) of the Mahabharata those that bring their own neuroses and neo-colonial prejudices!

Bhishma, who took a vow of celibacy to ensure that his stepmother Satyavati’s sons would reign, and yet who ended up acting as father to three generations of Kurus – Satyavati’s sons Vichitravirya and Chitrangada; then Dhritarashtra, Pandu, and Vidura; and finally the Pandavas and Kauravas. Bhishma, who renounced the throne and yet ruled Hastinapura as the regent for most of his life, on behalf of his step-brothers and step-sons. Bhishma, who took a vow of lifelong bachelorhood and yet was cursed by a woman – not for harassing or molesting her, but for not marrying her! Not quite the life a celibate bachelor would have imagined. His own father’s boon to him – that of choosing the time of his own death – would see him lie on the battlefield of Kurukshetra for fifty-eight nights, pierced with arrows shot at him by his beloved grandson Arjuna.

What about Kunti? A youthful indiscretion on her part led her to first abandon her first-born son, hide the truth from all for as long as Karna lived. Kunti, who chose her meeting with Karna, before the war, to not accept him as much as to ask him to spare her beloved Arjuna’s life? Did Kunti do the right and just thing by asking the Pandavas to share what they had brought her – Droupadi? Or was Kunti acting out of a desire to prevent strife between the brothers, who had all been smitten by Droupadi’s beauty? Certainly Kunti harboured at least some amount of resentment at her father, who had given her away to Kuntibhoj. But what about the Kunti who had to share her husband with the beautiful Madri, and who had to live with the knowledge that her husband had died a happy man in the arms of Madri? What about Kunti who had to live almost her entire adult life in hardship, deprived of companionship after the death of her husband, and then the company of her children after the game of dice?

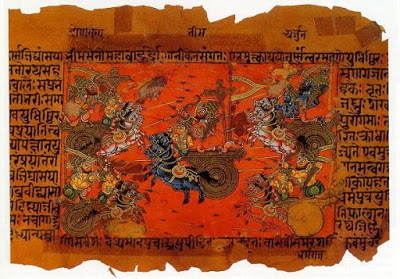

Yudhishthira losing the game of dice and the disrobing of Draupadi (credit: Illustration from Persian Mahabharata, HareKrsna.com)

Yudhishthira as the eldest Pandava was the embodiment of dharma. Yet it was he who lost not only his kingdom, but also his brothers, and ultimately even his wife – in a gambling match. Who would not utter a falsehood, except on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, and that too to trick his guru into laying down arms. Yudhishthira, who would not utter a lie – even if it meant staying silent when questioned pointedly by Duryodhana after the first gambling match (Dyuta Parva).

Karna, who heard the truth about his birth, from no less than Krishna and then his mother, Kunti. Yet who chose to fight on the side of the Kauravas, against his own brothers. The great warrior who chose to sit out of more than half of the greatest war fought so as to not fight under Bhishma’s command. Had Bhishma and Karna fought together, would the result of the war not been different? Did Bhishma deliberately provoke and belittle Karna’s prowess as a “rathi” – he admitted as much on his deathbed, but was the needling also meant to provoke Karna from sitting out of at least part of the war? Did Karna not wrong his friend Duryodhana by giving the vow he gave Kunti? Would not have the death of Bhima broken the back of the Pandava army, for, was it not Bhima who killed every one of the one hundred Kauravas, including Duryodhana in the famous gada-yuddha? Karna was the one who abused Droupadi as a courtesan, but was it not Karna who expressed regret at these harsh words he had spoken – to no less a person than Krishna?

Upayaja pointing Drupada towards Yaja. (credit: Mahabharata, published by Gita Press. via Wikipedia, the

free encyclopedia)

Drupada fought the war partly out of his desire for revenge against Drona, but also because of the compulsions of his filial duties that his daughter’s marriage to the Pandavas begat. His son Dhrshtadyumna avenged his father by beheading Drona, but not before Drona had killed Drupada. The cycle of revenge did not end there. Less than a week later, Drona’s son Ashwatthama would kill Drupada’s son Dhrshtadyumna, his transgender offspring Shikhandi, and every single one of his grandsons – the five sons of Draupadi through the five Pandavas. The burning fire of revenge, of whom the physical manifestations had been Dhrshtadyumna and Droupadi, was quenched, but at a terrible cost. Wasn’t it all because Drupada’s ego believed a poor ascetic as Drona not worthy of his friendship? Or was it because Drona would not accept the reality of adulthood was different from the magical myth of childhood?

Ghatotkacha, Bhima’s son from Hidimba, and the eldest among the children of the Pandavas. He who was invincible in battle during night, but who Krishna wanted dead – but only after Ghatotakacha was the fodder that was used to quench the fire of Karna’s shakti weapon. Ghatotakacha’s death gave Arjuna life. Because, didn’t Krishna tell Arjuna that the combined might of Jishnu and Vishnu would not have been able to counter Karna’s Shakti weapon?

Then, there is Shikhandi. What can we say about him, her? Amba in her previous birth, born to Drupada as his eldest daughter in the next, Shikhandi carried the burden of not only her father’s desire for revenge against Drona, but also of her own debt from her previous life. Amba’s (perceived) injustice at the hands of Bhishma, Drupada’s (perceived) insult at the hands of Drona – both had to be avenged. This all-devouring blaze had consumed Shikhandi in her previous life – metaphorically as well as literally. Never able to live life on her own terms, in either of her lives, she could not even have the unalloyed joy of avenging herself by killing Bhishma, since the arrows that penetrated Bhishma the deepest were the ones shot by Arjuna. Yes, she became the cause of Bhishma’s death, but it was a Pyrrhic victory.

What of Krishna Dvapayana, the father of the Kurus who fought on the plains of Kurukshetra? Who warned his mother Satyavati and dughters-in-law Ambika and Ambalika of the impending doom of the Kuru lineage and took them to the forest. But who gave the same advice to the Pandavas, only thirty-six years after the war, after they had witnessed the death and destruction of their entire kith and kin – their sons, brothers, cousins, fathers, teacher, Krishna, the entire Yadav race, all.

Lastly, what about the other Krishna, the great Madhusoodana? Who “danced with joy” upon witnessing Ghatotakacha’s death; who calmly and smilingly accepted Gandhari’s curse after the war. But hadn’t he calculatedly initiated the sequence of events that led to the destruction of the Yadavas even before the war, when he had nudged Duryodhana into choosing Krishna’s army to fight on the side of the Kauravas, knowing fully well that every one of the eleven Akshaunis of the Kaurava army would be destroyed? Isn’t one at least partly correct when one calls the entire Mahabharata a lila of the great Keshava?

Dharma is subtle.

Featured Image: Wikipedia

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Abhinav Agarwal is a son, husband, father, technologist and an IIM-B Gold Medalist.