Introduction

The Citizenship Amendment Bill proposes to give refuge to Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Buddhists of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh in India without any additional proof for religious persecution and subsequently offers citizenship after a stay of 6 years. The Bill has been passed in the Lok Sabha, but is yet to be tabled in the Rajya Sabha. The principal beneficiaries of the bill would be the Indics (Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists) of Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, given that the fraction of Christians in these countries is very small. We argue below that civilizationally, demographically, historically and morally, Indics ought to have special rights on India. We accordingly make our case for declaring India as the home of persecuted Hindus all over the world. Ignoring the Christian beneficiaries, the bill makes a tentative steps towards acknowledging this truth. We make our case for declaring India as the home of persecuted Hindus all over the world.

Section A: A Civilizational Necessity

Section A.1: Indian Nation and her Hindu Civilizational roots

In today’s world the only large state in which Hinduism is predominant (numerically, but not reflected in its state institutions or Constitution) is the current Indian state. The civilizational rights of Hindus on the current Indian state is founded on the basis of the very existence of the Indian nation and Indian nationhood that precedes the modern state’s origins. For, “a nation never means a land as such. A nation indicates a group or a community of people which has been traditionally living in a particular land, which has its own distinctive culture, and which has an identity separate from other peoples of the world by virtue of the distinctiveness of its culture. The cultural distinctiveness of a nation may be based on its race, or religion, or language, or a combination of some or all of these factors, but all-in-all there has to be a distinct culture which will mark the nation out from peoples belonging to other lands. Third, there may be internal differences in several respects among the people belonging to this culture, but in spite of these differences there is an overall sense of harmony born out of the fundamental elements of their culture, and a sense of pride which inspires in them a desire to maintain their separate identity from the rest of the world. Finally, as a result of these factors, this group of people has its own outlook towards the history of its traditional homeland; it has its own heroes and villains, its own view of glory and shame, success and failure, victory and defeat.’’ p. 3, [22]

India existed as a nation long before any of the two major Abrahamic religions – Islam and Christianity, were born, and the she has been civilisationally Hindu from ages. Hinduism has been associated with every nook and corner of what is currently termed the Indian subcontinent, and slightly beyond, into Afghanistan, and parts of what is now Iran and the adjoint areas of Central Asia. We denote this region as civilizationally Hindu. In due course, some other schools of thought or spirituality emerged from Hinduism, namely Jainism, Buddhism, Sikhism, etc. Owing to specific sequence of socio-political course of events, these schools of thoughts have been deemed as separate religions, but their essential convergence with Hinduism is inescapable. For one, the sacred places, the pilgrimages of all the above-mentioned religions, including of course Hinduism, are located in the region that is civilizationally Hindu. We find references to Jambudvipe Bharatkhanda in every Sanskrit Sankalpa p. 9, [23]. In the words of Sitaram Goel, “The Ramayana, the Puranas, the DharmaShastras, paint the same portrait of an ancient land, every spot of which is sacred to some cultural memory or the other. The Jainagama and the Tripitaka speak again and again of the sixteen Mahajanapadas which spanned the spread of Bharatavarsha in the life-time of Bhagvan Mahavira and the Buddha. Even a dry compendium on grammar, the Ashtadhyayi of Panini, provides a near complete count of all the Janapadas in ancient India-Gandhara and Kamboja, Sindhu and Sauvira, Kashmir and Kekaya, Madra and Trigarta, Kuru and Panchala, Kaushala and Kashi, Magadha and Videha, Anga and Vanga, Kirata and Kamarupa, Suhma and Udra, Vatsa and Matsya, Abhira and Avanti, Nishadha and Vidarbha, Dandakaranya and Andhra, Karnataka and Kerala, Chola and Pandya. The epic poetry poured out by Kalidasa, Magha, Bharavi and Sriharsha, continues the same tradition of talking endlessly about Bharatvarsha as a single and indivisible geographical entity, as a Karmabhumi for Gods and Goddesses, Brahmarshis and Rajarshis, and as higher than heaven for all those who have had the good fortune of being born in it’’ p. 11, [23]. It was a feeling of civilizational nationhood that lead “Adi Shankaracharya traverse India from its Southernmost tip to the farthest corners of Bharatvarsha in North and East and West and helped him found (or revive) the foremost Dhamas at Badrinath, Dwarka, Rameshwaram and Puri. There is no count of sadhus, sanyasins and householders who have travelled ever since on the trail blazed by the great Acharya. Six and a half centuries later, Guru Nanak Dev followed in the footsteps of the Pandavas and the Shankaracharya in search of spiritual company.’’ p. 12, [23]. Chaitanyadeva who lived in the 16th century also roamed over the same route p. 12, [23].

The account left by invaders at various times has been consistent with those of Indic texts and Chinese travellers’ accounts. As Sitaram Goel writes, “the Macedonian invader had proclaimed that he had entered India only after he had crossed what is now known as the Hindukush mountain. Greek historians leave no doubt that the army of Alexander which retreated by the land route through Baluchistan regarded itself as still inside India, and not free from the danger of Indian counterattacks, till it had crossed over the desert of Makran.’’ p. 14. [23]. Sally Hoven Wriggins, writing about the travels of Xuanzhang who visited India from China in the 7th Century AD concurs, “Indeed, when Xuanzhang finally reached the neighborhood of Langham near Jalalabad, he felt, as Alexander the Great had, nine centuries earlier, that he had entered a new world. Evidently, Xuanzhang, like Alexander, must have been aware of having reached the gate of a kind of promised land p. 56, [24]. Foreign nationals who have visited India at different times have left precise accounts of her boundaries. The pilgrims from China, Fa-Hien, Hiuen-Tsang and It-Sing who came to India in the 4th, 7th and 8th century AD “found themselves in the sacred land which they came to visit as soon as they stepped into what is now known as Afghanistan. Many other lands beyond the North West province of India worshipped the Buddha and were dotted with Buddhist temples and monasteries. But the Chinese pilgrims did not experience the same spiritual stir in those lands as they did on entering the holy land which had given birth to the Buddha’’ pp. 11-12. [23]. Xuanzhang named the country as Indu, and described its territory as “was above 90,000 li in circuit, with the Snowy mountains [the Hindu Kush] on the North and the sea on its three other sides. It was politically divided into above seventy kingdoms ; the heat of the summer was very great and the land to a large extent marshy. The Northern region was hilly with a brackish soil; the East was a rich fertile plain; the Southern division had a luxuriant vegetation; and the West had a soil coarse and gravelly.’’ p. 56, [24].

Also, “The Arab chroniclers recorded again and again that the armies sent by successive Caliphs against Kabul and Zabul and Sindh had gone out for the conquest of Hind.’’ p. 14. [23]. Al Beruni who visited Indian in 1017 AD wrote that “ The Hindus believe that there is no country but theirs. no nation like theirs, no king like theirs, no religion like theirs, no science like theirs’’ p. 22, [52]

Section A.2: Defense against invaders – Indic in ethos and in participants

Motivated by the ethos of Hinduism, it has been the practitioners of Hinduism (and Sikhism) who have resisted invaders with all their might for the last 2000 years of documented history, starting from the Huna and the Saka invasions, moving on to the Muslim invasion and ending with the European invasion. Starting from the motivating ethos, Ramayana said: “Janani, janmabhumi Swargadapi Gariyasi’’ – mother and motherland excel Heaven in divinity. The conflation of motherland with religious divinity is uniquely Hindu in today’s world and it is this ethos that has dominated Indian nationalism throughout the ages. Today Hinduism is the only major religion that ascribes divinity to the feminine. Hindus worship mother Goddesses as embodiments of strength (Durga), knowledge (Saraswati) and wealth (Lakshmi). The holiest river for the Hindus is Ganga, a feminine. We document that the unique Hindu ethos of worshipping the feminine has constituted the core of their resistance against the invaders.

The 150 chiefs who assembled under Prithviraja III in his final battle against Muizuddin Ghori had “sworn by the water of the Ganges, that they would conquer their enemies, or die martyrs to their faith.’’ pp. 98-99 [25]. In South India, Vijayanagar empire constituted the bulwark of the Hindu defense against the Muslim invaders. They explicitly mentioned that they were working to eliminate the Islamic rule and its atrocities against the Hindus. Their war cries rang `Jai Bhuvaneshwari!’ and `Jai Viroopaksha’. In Madhura Vijaya, Gangadevi clearly bemoans that in the country of Madurai sultanate, against which Kamparaya went to war to stop the atrocities of the Turushkas, the following happened, which were horrifying to the people.

ಸತತಾಧ್ವರಧೂಮಸೌರಭೈಃ ಪ್ರಾಙ್ನಿಗಮೋದ್ಧೋಷಣವಧ್ಭಿರಗ್ರಹಾರೈಃ।

ಅಧುನಾಜನಿ ವಿಸ್ರಮಾಂಸಗನ್ಧೈರಧಿಕಕ್ಷೀಬತುಲುಷ್ಕಸಿಂಹನಾದೈಃ।। (೮) [38]

Translation: Where once, due to the continuous performance of yagnas, there was the fragrance of burnt clarified butter, and the sound of the chants of the Vedas, in the villages, now, there is the smell of burnt raw flesh and the world is split by the roars of the Turushkas.

ಸ್ತನಚನ್ದನಪಾಣ್ಡು ತಾಮ್ರಪರ್ಣ್ಯಾಸ್ತರುಣೀನಾಮಭವತ್ಪುರಾ ಯದಮ್ಭಃ।

ತದಸೃಗ್ಭಿರುಪೈತಿ ಶೋಣಿಮಾನಂ ನಿಹತಾನಾಮಭಿತೋ ಗವಾಂ ನೃಶಂಸೈಃ।। (೮) [38]

The river Tamraparni, which was once white due to the sandal paste applied by the women to their bodies, is today, red due to the flowing blood of the cows that have been slaughtered by the wicked men.

After the conquest of Madurai by Kamparaya, she is clear that the proper order returned and the country was cleared of the Muslim terror, as she states `ಕಲಿನ್ದಜಾ ಮರ್ದಿತಕಾಲಿಯೇವ ದಿಗ್ದಕ್ಷಿಣಾಸಿತ್ ಕ್ಷತಪಾರಸೀಕಾ‘ [38], which means “Just as Yamuna was freed of terror after the subduing of Kaliya, the south became free of the terror of the Parasikas’’. Note, river Yamuna is considered feminine.

Similarly, Rajanatha Dindima is clear that Narasa Nayaka went to war against the Bahmani sultans to restore the proper order [against Islamic oppression]. He states,

ಮಹೀಪತಿರ್ಮಾನವನಾಮ ದುರ್ಗಂ

ಶಕಾಧಿನಾಥೇನ ಸಮಂ ಗೃಹೀತ್ವಾ

ಸ್ಫುಟೀಚಕಾರಾಸ್ಯ ಪುನರ್ವಿತೀರ್ಯ

ಶೌರ್ಯಂ ತದೌದಾರ್ಯಮವಾರ್ಯಚರ್ಯಮ್ 1:29, [39]

The king seized the fortress named Manava from the Shaka king of the place, and destroying his [the Shaka king’s] power, once more established the proper order of things, in valour and generosity.

The Sisodias of Mewar, the clan that produced Rana Pratap, the most formidable foe of Akbar, drew strength from the worship of Shakti; their Kuladevis were Amba, Kalika, Baan Mata, different forms of Shakti (Chapter 2, Kuladevi tradition Myth, Story and Context [49], [50]). Pratapaditya, from Jessore, mounted one of the foremost challenges to the supremacy of Akbar – Jessoreshwari Kali, was the presiding deity of his kingdom. Shivaji who stalled the religious bigot and tyrant, Aurangzeb, drew strength from the worship of Tulja Bhavani. ‘उदे उदे ग अंबाबाई’, and “आदी शक्ती तुळजा भवानी जोगवा दे“ are till date famous prayers of Tulja Bhavani among the Marathas. In honor of Durga, Shivaji’s teacher and religious mentor (guru) Ramdas had composed:

दुर्गे दुर्घट भारी तुजविण संसारी।

अनाथ नाथे अम्बे करुणा विस्तारी।

वारी वारी जन्म मरणांते वारी।

हारी पडलो आता संकट निवारी॥

Guru Govind Singh who seeded the Sikh resistance against the Mughals composed Chandi Di Var in honor of Durga as Chandi or Mahakali:

चिंतन कुरू मा महाकाली देवाक्षी।

रूद्रकाली सा महामाया राक्षसमारणे॥

“Raise your awareness towards the eye of the Devas, i.e. Mahākāli

Rudrakali, is she who is this great veil for the slaying of the demons.”

During the freedom struggle against the British, Bankim Chandra composed his `Bande Mataram’. Emily Brown writes how Bande Mataram inspired revolutionaries across India: “Although a Maharashtrian, Savarkar was quick to use Bankim Chandra Chatterji’s Bande Mataram (Hail Motherland) as the “national hymn,” and this song was frequently heard to resound through the halls of India House and invariably used to open every meeting or conference. The two words, Bande Mataram, became the shibboleth of the extremists and were used in greeting and salute in much the same way the Nazis used Heil Hitler.” p. 62, [58] This song could inspire thousands of Indian revolutionaries to martyr themselves with the chant on their lips because it vocalised the heartfelt cry of millions of Hindus. It is this song that saw motherland as Goddess reincarnate, as a combination of Durga, Laxmi, Saraswati:

বন্দে মাতরম্।

সুজলাম্ সুফলাম্

মলয়জ শীতলাম

শস্যশ্যামলাম্

মাতরম্।

বন্দেমাতরম্।

ত্বম্ হি দুর্গা দশপ্রহরণধাহিণী

কমলা কমলদলবিহারিণি

বাণী বিদ্যদায়িনী

নমামি ত্বম্

নমামি কমলাম্

অমলাং অতুলাম্

সুজলাং সুফলাম্ মাতরম্।

বন্দে মাতরম্।। ৪ ।।

It translates as:

Mother, I salute thee!

Rich with thy hurrying streams,

bright with orchard gleams,

Cool with thy winds of delight,

Dark fields waving Mother of might,

Mother free.

Thou art Durga, Lady and Queen,

With her hands that strike and her

swords of sheen,

Thou art Lakshmi lotus-throned,

And the Muse a hundred-toned,

Pure and perfect without peer,

Mother lend thine ear,

Rich with thy hurrying streams,

Bright with thy orchard gleems,

Dark of hue O candid-fair

Songs that celebrated the nation as mother Goddess subsequently appeared in multiple regional languages, particularly in Bengal which was at the forefront of the armed incursions against the British: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=twsHQPBJnLA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tqnq-6dCaW0 . We transcribe one such song, composed by Atulprasad Sen in Bangla script:

উঠ গো ভারত–লক্ষ্মী, উঠ আদি–জগত–জন–পূজ্যা,

দুঃখ দৈন্য সব নাশি করো দূরিত ভারত–লজ্জা।

ছাড়ো গো ছাড়ো শোকশয্যা, কর সজ্জা

পুনঃ কনক–কমল–ধন–ধান্যে!

জননী গো, লহো তুলে বক্ষে,

সান্ত্বন–বাস দেহো তুলে চক্ষে;

কাঁদিছে তব চরণতলে

ত্রিংশতি কোটি নরনারী গো।

Next,“When Bengal was partitioned in 1905, in Calcutta, gatherings of 50,000 people took a collective oath before Goddess Kali in the holy Kalighat temple that they would throw the British out of our homeland. Numbers touching 50,000 marched through the streets after taking a dip in the holy Ganges, anointing their foreheads with tilak, and holding copies the Bhagvad Gita in their hands’’ pp. 9-10, [22].

Aurobindo, who was at the forefront of the anti-partition agitation and organized armed insurgencies against the British, began his lectures and speeches often with a prayer to Chandikaamba. Invoking the Goddess Durga to lend aid to the Freedom Struggle, Aurobindo wrote

মাতঃ দুর্গে! সিংহবাহিনি সর্ব্বশক্তিদায়িনি মাতঃ শিবপ্রিয়ে! তোমার শক্ত্যংশজাত আমরা বঙ্গদেশের যুবকগণ তোমার মন্দিরে আসীন, প্রার্থনা করিতেছি,– শুন, মাতঃ, ঊর বঙ্গদেশে, প্রকাশ হও।।

“Mother Durga! Rider on the lion, giver of all strength, Mother, beloved of Shiva! We, born from thy parts of Power, we the youth of Bengal, are seated here in thy temple. Listen, O Mother, descend upon earth, make thyself manifest in this land of Bengal.’’ [28].

In an address delivered before the Royal Empire Society on November 1, 1932, Charles Tegart (C.S.I., C.I.E., M.V.O), had described the start of the revolutionary freedom fight movement in Bengal as follows: “Having collected a few disciples, Barin, who was shortly followed to Calcutta by his brother Arabindo, started by publishing in 1905 a pamphlet entitled “Bhowani Mandir”, the Temple of Bhowani. Bhowani is one of the many names of the goddess Kali, the Goddess of destruction, the Mother of Strength, who according to Hindu mythology, was created by the gods to destroy the demons who had usurped their kingdom. The idea Barin taught was, roughly, that Kali, the avenger whose many hands dripped with blood, was not a symbol of savagery but of selflessness. As Kali drove out the demons so should they, strengthened by the worship of Kali, drive out the Feringhee, a contemptuous name for the European’’ p. 8, [29]

Tegart had joined the Indian Police Service in 1901 and served almost continuously in Bengal for a period of thirty years until he was appointed a member of the Secretary of State’s India Council in December 1931. For the last eight years of his service in India he was Commissioner of Police, Calcutta. The lecture was delivered with the former British Governor of Bengal, Stanley Jackson G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E., in the chair (foreword [29]). In the same lecture, Tegart described the initiation ceremony for revolutionaries in the Anushilan Samity, which was at the forefront of the revolutionary movement in Bengal, as follows: “ Four vows of increasing import were administered before the Goddess Kali to all recruits, a remarkable system for the progressive enthralment of the initiates, who undertook to stake their lives and all they possessed, forsake all family ties, obey all orders from their leaders without question, and never divulge any secrets on pain of death, a penalty which was often inflicted on those who wavered’’ p. 9, [29].

Dhananjay Kheer has written in a biography of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, about Savarkar’s reaction when he heard about the martyrdom of the Chapekar brothers: “It drove the boy Savarkar to a grim resolve. He approached the family deity, Durga, the Ashtapraharana Dharini, in the sanctuary and invoked the blessings of the Great Mother, the source of divine inspiration and strength. Sitting at the feet of the armed Goddess Durga at dead of night, he took a vow of striving nobly and sacrificing his nearest and dearest, his life and all, to fulfil the incomplete mission of the martyred Chaphekars. He vowed to drive out the Britishers from his beloved Motherland and to make her free and great once again’’ [53] In the first decade of the twentieth century, the residents of the India House, a congregation of the Indian revolutionaries in London, which Savarkar led, used to take the following oath: “In the sacred name of Chhatrapati Shivaji, in the name of my sacred religion, for the sake of my beloved country invoking my forefathers, I swear, that my nation will be prosperous, only after freedom, full freedom is achieved. Convinced of this, I dedicate my health, wealth and talents for the freedom of my country and for her total uplift. I will work hard to my utmost capacity till my last breath. I will not spare myself or slacken in this mission. I will follow all the rules and regulations of Abhinava Bharat. I will never disclose anything about the organization” p. 30, [58] Hindu ethos is evident in this oath. Later, even after becoming an atheist, Savarkar, composed `Jayostute’ – a prayer where he saw Freedom as his Goddess.

जयोस्तु ते श्रीमहन्मंगलेIशिवास्पदे शुभदे

स्वतंत्रते भगवतिIत्वामहं यशोयुतां वंदे II

[Victory to you, O Auspicious One, O Holy One (also Abode), O Granter of Joy,

O Goddess of Freedom, Victorious One, we salute you]

One of the eminent leaders of the freedom struggle, Subhas Chandra Bose, who sought to liberate India through military action, conflated motherland with was Shakti Goddess, as Durga or Kali p. 123 [30] . On 26/12/1925, from Mandalay jail in Burma, he wrote to his sister-in-law, “ In Durga, we see Mother, Motherland and the Universe all in one. She is at once Mother, Motherland and the Universal spirit.’’ p.170, [27] Shakti worship had formed an important component of his struggle against the British. On 18 February, 1926, again in Mandalay jail, he had organized a fast in protest against the authorities who denied financial allowances to the prisoners for conducting Durga and Saraswati Puja pp. 221-226, [27]. On December 9, 1930, he had called upon the women to participate in liberation struggle, invoking the imagery of asuradalani Durga: “`Women had not only duties to their family, but they had also a greater duty to their country. When the gods found their sliver almost vanquished in their fight with the demons, they invoked the help of “sakti” in the form of mother. The country was in a sad plight, therefore the country looked up to the mothers to come forward and inspire the whole nation.’’ p. 238, [30] Years later, when he was illegally incarcerated, in Presidency jail, he announced at fast unto death in protest. He announced it on the sacred day of Kali puja (30.9.1940) to affirm his faith. He wrote to the Superintendent of Prison: “There is no other alternative for me but to register a moral protest against an unjust act and as a proof of that protest, to undertake a voluntary fast. This fast will have no effect on the `popular’ ministry, because I am neither the Maulavi of Murapara, Dacca nor a Muhammadan by faith. Consequently, the fast will, in my case, become a fast unto death. … Britishers and the British Government have been talking of upholding the sacred principles of freedom and democracy, but their policy nearer home belied these professions. They want our assistance to destroy Nazism, but they have been indulging in super-Nazism. My protest will serve to expose the hypocrisy underlying their policy in this unfortunate country-as also the policy of a Provincial Government that calls itself `popular’, but which in reality, can be moved only when there is a Muhammadan in the picture…..I repeat that this letter, written on the sacred day of Kali Puja, should not be treated as a threat or ultimatum. It is merely an affirmation of one’s faith, written in all humility.’’ pp. 187-189, [26].

The worst atrocities perpetrated on the religion, culture and livelihood of the tribals were by the British during their regime, and by the Christian missionaries subsequent to the transfer of power in 1947. It is the tradition of Shakti puja that inspired them to mount the desperate resistances they could despite severe limitation of resources in comparison to that of their adversaries. We now narrate in greater detail the relation between Durga Puja and the tribal rebellion led by Brojo and Durga Murmu in the current Jharkhand and West Bengal. The year was 1907 and the region, the Sulunga village of Birbhum, WB, then inhabited by the Santhal tribe. Birbhum district left front chairman, Arun Chowdhury, describes: “the zamindari of this area was given away to one Kerap saheb from Bihar, who resorted to violence to collect taxes from poor peasants”. “Those who failed to pay the tax on time were forcibly sent to Assam, where they had to work as coolies (porters). However, Kerap saheb had once announced that if the defaulters convert to Christianity they would be exempted from paying taxes. While a few chose to do so, most revolted against the landlord under the leadership of Brojo Murmu (who belonged to Sulunga). It was Brojo Murmu who introduced this Durga Puja. The puja has been performed every year since then ” [48]. Brojo Murmu, worshipped `Mahishasuramardini` – “the warrior form of the goddess – some 100 years ago. It was intended to unite Santhals living in the bordering areas of Birbhum and in the Jharkhand region against oppressive British rule. Priest Robin Tudu, who has been overseeing the puja here for over two decades now, said: “An animal sacrifice is made on Ashtami, usually a white goat, as according to local belief a white goat symbolises `gora sahib` (the whiteman)”.’’ [48] Tapan Murmu, a descendant of Brojo Murmu’s family said: “Many years ago, our ancestors Brojo Murmu and Durga Murmu were inspired to overpower the British rulers by uniting our people by initiating the worship of Durga as the goddess of Shakti.” [48]

Given that Hindu ethos formed the cornerstone of the resistance against invaders, it is only to be expected that the participants of resistance movements would be primarily Hindu. During invasion by Muslims, this would be a given. We therefore present some limited data on religious demographics of freedom fighters in the era of European invasion. In the earlier referenced address delivered before the Royal Empire Society on November 1, 1932, Charles Tegart (C.S.I., C.I.E., M.V.O) stated that “The first point I would like to impress on you is that terrorism (like, indeed, civil disobedience) is essentially a Hindu movement’’ pp. 3-4, [29] Here the armed revolutionary freedom fight against the British is being referred to as “terrorism’’. Srikrishnan Saral has attempted a comprehensive study of Indian revolutionaries between 1757 and 1961 – he considered all those who participated in armed freedom fight against the Europeans (British, Portugese) as revolutionaries [48-52]. A religious demography decomposition of the names he provides is consistent with Tegart’s observation. He lists 118 Indics (Hindus and Sikhs) between 1770-1910, 1 Parsee and 13 Muslims [31]. Note that documentation would be relatively sparse for the period between 1770 to (and including) 1857, and this is the period in which larger number of Muslims had participated; yet it is also true that the motivation of the Muslim participants during this period was often religious “Jihad’’ against “infidel’’ Europeans (and at times Hindus), rather than patriotic. During 1910-1920, considering the Gadar Party and other revolutionaries in the USA and Canada during the First World War period, Saral lists 165 Indics and 18 Muslims [32]. It must be remembered that a significant number of Muslims who fought against the British during the First World War were Pan-Islamic warriors, not Indian freedom fighters. They were heeding the call given by the Khalifah of Turkey to fight a Jihad against the British [44]. In Kakori, Chattogram and Quit India movements, Saral lists the names of 490 Indics and 6 Muslims as resisting the British with arms [34]. Saral lists 84 Indics and 1 Muslim other revolutionaries of the 1920s and 1930s (excluding Kakori and Chattogram) [33] (The last two periods would have been Tegart’s focus). Finally, considering the members of the Indian National Army, resistance movements in Hyderabad and Goa, Saral lists 237 Indics, 47 Muslims and 3 Christians [35]. The increase in the Muslim percentage is because the Indian National Army had to be restricted to the prisoners of wars from the British Indian Army, which had a relatively high percentage of Muslims (Punjabi Muslims were heavily represented in that segment). But even in this segment Muslims comprise only 16.37% of the total number of names though they constituted about 24% of the population of undivided India at that point. Overall there are 1094 Indics, 87 Muslims, 1 Parsee and 3 Christians. Thus, 92.32% of armed freedom fighters were Indics, though they constituted only 75% of the overall population; the fraction would be even higher if we discount those joining 1857 war of independence to establish supremacy of Islam. If we consider the revolutionaries the British dreaded the most, that is, the political prisoners they had deported to Cellular, between 1909-38 only 10 of 565, that is less than 2 % were Muslims pp. 342-360, [40]. Before, 39 out of 309 (ie, 12.62%) deported to the Andamans during 1857 were Muslims pp. 328-339, [40], and 16 out of 22 between 1857 and 1908 were Muslims, pp. 340-341, [40]. Overall, 6.1% of the Andaman deportees would be Muslims (even including the struggles motivated by establishing the supremacy of Islam). Hindustan Socialist Republican Army had published a list of Indians who were executed by the British, or had died in hunger strike against them in jails, between 1883-1943 [45]. The list comprised of 121 names among which only 4 are Muslims and 1 Christian; thus a whopping majority of 95.87% were Indics. If we consider those that died in direct conflict with the British during this period, we obtain 27 more names (Chattogram revolutionaries, Benoy Bose, Badal Gupta, Chandrasekhar Azad), all of which are Indic, enhancing the percentage of Indics to 96.62. Thus, individuals practicing other religions such as Islam and Christianity have joined freedom struggles at times, but the core came from Hinduism (and Sikhism). Muslim masses participated only when pan Islamic movements like Khilafat became allied with the freedom struggle, as during 1921, or when the struggle against the British also explicitly called for Jihad as during 1857. Thus, to be specific, Muslim masses never participated in freedom fight, per se, but in anti-British movements which sought to establish the supremacy of Islam. All these are pertinent and operative differences between religions that originated in civilizational Hindu, and those that originated elsewhere, eg, Islam and Christianity.

Section A.3: Separatism – driven by ethos and practitioners of non-Indic religions

Separatist movements have been sustained on a long term only by segments of the populace whose religions are not those that originated in the civilizationally Hindu region. One such separatist movement have led to the vivisection of India in 1947, despite vigorous opposition by Hindus (and Sikhs). In 1946 Congress contested the elections on the plank of opposing Pakistan. It stood for Indian freedom with unity pp. 558, 559, [30]. Historian Leonard Gordon writes, “The Muslim League had fought the election on the plank of Pakistan and protection of Muslim interests and rights. Hashim (Suhrawardy’s second-in-command in Bengal), general secretary of the League and a kind of Islamic socialist, had put forth his views in ‘Let Us Go to War’’ p. 560, [30]. The Congress and the Muslim League respectively swept the non-Mohammedan and Mohammedan seats all over India [41]. The Congress won 91% of the vote in the non-Muslim constituencies, while the Muslim League swept the Muslim constituencies [41]. In Bengal Congress swept the six non-Mohammedan seats including the landholders’ seat. In the Bengal Legislative Assembly Congress won a great majority of the non-Muslim seats p. 559, [30] In Bombay and Madras, the Muslim League swept all the seats, while in United Provinces and Bihar, it won 54 of the 64 and 34 of the 40 seats respectively. In Punjab, it swept 73 of the 85 Muslim seats [41].

The Muslim League won all the Mohammedan seats in Bengal in the Central Legislature, and 113 out of 121 Muslim seats in Bengal Legislative Assembly, defeating the nationalist Muslim candidates. Fazlul Huq won his own seat in the Bengal Legislative Assembly but his Krishak Praja Party was non-existent otherwise. A similar thing happened to the Unionist Party in Punjab. They who had trounced the Muslim League in 1937, but they were completely routed in 1946 elections, winning only ten out of the 175 seats in the Punjab legislature [57]. Mock funerals were held outside the residence of Khizr Hayat Tiwana and he was denounced as a `kafir’ by the Muslim League, and he had lost all credibility [57]. Congress leader S. M. Ghosh maintained that the League won because of its goondas rather than because of the popularity of its program, but this is unlikely to be the case given that it had won 2036775 out of 2434100 Muslim votes for the Bengal Legislature p. 559, [30].

The electoral success of Muslim League in the Mohammedan seats isn’t considered an adequate evidence of the popular support for partition among the Muslim masses as universal adult franchise was not the norm, and only an electoral college comprising of economically advanced sections of various communities could vote. But several unimpeachable sources have negated this view. Historian Leonard Gordon opines, “This [electoral success of Muslim League in Mohammedan seats] was strong evidence of the popular backing that the Muslim League had achieved during the latter years of the war. The polarization of Hindus and Muslims had grown and a popular Muslim party of any weight independent of the League no longer existed ‘’ p. 559, [30] For example in Bengal, the prominent Krishak Praja Party leaders, and the student community had shifted to the League. After the elections, seeing the writing on the wall, the leader of the Krishak Praja Party, Fazlul Huq once again applied to join the Muslim League pp. 559, 560, [30]. Contemporary records provide compelling evidence that the demand for Partition came from the Muslim masses. In May 1946, in a statement titled “The Present Political Stand of the R.S.P.I’’ , the Leftist Revolutionary Socialist Party of India (R.S.P.I.) stated: “But the Convention is fully alive to the fact that the sentiment of the Muslim masses of India in favour of Pakistan has already been worked upto a great pitch. And as such serious difficulties are being encountered by the workers of R.S.P.I. while repudiating the Pakistan of the Jinnah brand.’’ pp. 153-154, [21] R.S.P.I can surely not be accused of a Hindu communal viewpoint, it served as a long time partner of the CPIM in the Left Front Coalition Government in West Bengal from 1978-2011. Also, author Nandita Bhavnani recounts that the Sindhi Hindus opposed partition of India. She writes, “ According to Vishnu Sharma, Dr. Choithram Gidwani said in his speech [on 14 June, 1947]: “There is neither justice nor any matter of principle that those who have to suffer the most from Partition are not given a voice, and no plans are being drawn up for their safety.” Loc. 971-980, [16], and “ Many Sindhi Hindus of that generation say that they remember that national-level Congress leaders such as Gandhi and Nehru had earlier claimed that Partition would take place over their dead bodies; they had banked on these assurances and now they felt betrayed.’’ loc. 989, [16]. This is one of many evidences that Hindu masses opposed partition. But partition could not be averted and resulted in Muslim theocratic states that persecuted citizens practising Hinduism, Sikhism and Buddhism, on the basis of their religions, and the current secular India (it is a different matter that the practitioners of Hinduism have been persecuted on the basis of their religion in parts of India in which they have been reduced to a demographic minority) like in Kashmir [17], Nagaland [18] and Mizoram [19].

Incidentally, limited separatist movements among the civilizationally Hindu demographics have often been led by those who converted to Islam, and became entrenched in support systems provided by neighboring primarily Muslim states. For example, the leader of ULFA, Paresh Baruah has embraced Islam and obtained a safe haven in Bangladesh. He is now Kamruj Zaman Khan, and his wife, born as Bobby Dutta is now known as Sofian Zaman. His family now lives in Bangladesh under the patronage of influential Islamic radicals. He has established a financial empire in Bangladesh in collaboration with local Muslim businessmen. Although in the 1980s ULFA started its movement mainly to drive out the millions of illegal Muslim migrants from Bangladesh, Baruah has publicly defended illegal Muslim Bangladeshi infiltrators living in Assam. Many of the Hindu leaders of ULFA have Muslim mistresses provided by the Bangladeshi intelligence. The ULFA separatist movement has now become the “Hindu mercenaries of the Jihadis’’ in the words of former RAW (India’s external intelligence agency) chief, [20], [36], [37]

Section B: Inference and Continuation

It is therefore a civilizationally and historically documented truth that no other segment of the populace is as vested in the current India as the Hindus (and Sikhs, Jains). India should therefore declare itself a natural home for persecuted Hindus (and Sikhs, Jains) all over the world. The Citizenship Amendment Bill is the first tentative step towards that end. In future it must be extended to include Hindus in Sri Lanka, who have also been persecuted on the basis of their religion, and other parts of the world where they constitute micro-minorities and have been similarly persecuted. Citizenship Amendment Bill does not take us there yet, but makes a good beginning.

The history of the separatist movements in India tell us that the integrity of Indian nation is damaged each time Hindus are reduced to a demographic minority in large regions. Hindu demography is indeed, therefore, the destiny of India. Statistical analysis of religious demography also reveals that Hindu demography is deeply endangered today across India. It is also this demography that the Citizenship Amendment Bill seeks to protect, and provide our destiny a last lifeline. In addition, the Citizenship Amendment Bill seeks to redress the sufferings of one Hindu ethnicity that have been historically discriminated against by the Indian state, the Hindu Bengalis, and primarily those from erstwhile East Bengal. This is because a very small percentage of Pakistan and Afghanistan is Hindu (and Sikh) today, while a somewhat higher percentage of Bangladesh (8.96%, according to census 2011 [43]) remain Hindu. Rescuing the latter segment of the populace will have a demographic consequence, it goes without saying that the humanitarian significance of saving even one victim of religious persecution in any of the countries named in this paragraph is immeasurably immense.

Thus, whether or not, the bill is anti-constitutional is a moot point, because Constitution is but a document framed by mortals who are prone to judgment errors and even compromise owing to patronage by vested interests, while civilizational and historical truths are foundational. Constitution have and continue to evolve to adapt to altered realities, knowledge and understandings. But, for the constitution aficionados, the civilizational and historical truths stated above, were voiced in the Constituent Assembly Debates too. On 11 August, 1949, P. N. Deshmukh had moved an amendment stating: “In the second sub-clause I have proposed, I want to make a provision that every person who is a Hindu or a Sikh and is not a citizen of any other State shall be entitled to be a citizen of India. We have seen the formation and establishment of Pakistan. Why was it established? It was established because the Muslims claimed that they must have a home of their own and a country of their own. Here we are an entire nation with a history of thousands of years and we are going to discard it, in spite of the fact that neither the Hindu nor the Sikh has any other place in the wide world to go to. By the mere fact that he is a Hindu or a Sikh, he should get Indian citizenship because it is this one circumstance that makes him disliked by others. But we are a secular State and do not want to recognise the fact that every Hindu or Sikh in any part of the world should have a home of his own. If the Muslims want an exclusive place for themselves called Pakistan, why should not Hindus and Sikhs have India as their home?” …“ I think that we are going too far in this business of secularity. Does it mean that we must wipe out our own people, that we must wipe them out in order to prove our secularity, that we must wipe out Hindus and Sikhs under the name of secularity, that we must undermine everything that is sacred and dear to the Indians to prove that we are secular? I do not think that that is the meaning of secularity and if that is the meaning which people want to attach to that word “a secular state”. I am sure the popularity of those who take that view will not last long in India.“ [54]. This amendment was opposed by Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar and Jawaharlal Nehru on 12 August 1949. The first said “We may make a distinction between people who have voluntarily and deliberately chosen another country as their home and those who want to retain their connection with this country. But we cannot on any racial or religious or other grounds make a distinction between one kind of persons and another, or one sect of persons and another sect of persons, having regard to our commitments and the formulation of our policy on various occasions.” [59]. The latter said “Now, all these rules naturally apply to Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs or Christians or anybody else. You cannot have rules for Hindus, for Muslims or for Christians only. It is absurd on the face of it; but in effect we say that we allow the first year’s migration and obviously that huge migration was as a migration of Hindus and Sikhs from Pakistan“ [60]. Nehru prevailed then, does not imply he should now; being on the wrong side of history he ought not.

Politically, this bill provides us stark differentiators – political parties that oppose it are definitively anti-Hindu; those, and only those that take it towards its logical conclusion (disregarding those that utilize it as an insincere election gimmick without any intention to see it through towards legislative sanctity) may be considered allies of Hindus, regardless of their other failings such as corruption and governance deficiencies, which incidentally constitute common shortcomings across the political spectrum.

Given its ramifications, the Citizenship Amendment Bill is being sought to be thwarted through a vicious campaign of disinformation. The primary beneficiaries of this act, the Hindu Bengalis, naturally constitute a collateral damage in this process. The disinformation campaign comprises of myths such as 1) Assam and the rest of North East have been overwhelmed by Hindu Bengali refugees in the past 2) speakers of Assamese have been reduced to a minority in their own state owing to the influx of such refugees 3) West Bengal have taken in negligible fraction of the refugees, and the bulk of the burden of the Hindu Bengali refugees have been borne by the rest of India 4) Hindu Bengali refugees are an indolent and pampered lot. We show the vacuity of all these myths, though not necessarily in that order. We also briefly touch upon the contributions of the primary beneficiaries, the Hindu Bengalis, towards the Indian nation and their sufferance at the hand of the British invaders owing to their service as the sword arm of the Indian nation. Remarkably enough the abhorrence of the Hindu Bengalis seem to have been transferred from the British invaders to their Indian successors. This abhorrence has expressed itself in discrimination meted out by the Indian state against the Hindu Bengalis. A full account of political, economic and ethnic discrimination launched by the Indian state on the Hindu Bengalis would easily consume a series, which this article does not attempt to narrate. Instead we focus on some specific aspects: 1) how repeatedly the land of the state formed for Hindu Bengalis, West Bengal, have been usurped and delivered to the Muslim majority East Pakistan and more recently to Bangladesh, 2) how Hindu refugees from East Bengal were discriminated against even in comparison to Hindu (and Sikh) refugees to India from elsewhere. We recommend that the interested reader refer to [2], [42] for documentations of economic discrimination against West Bengal.

We conclude this article with a rather puzzling issue. First, BJP is the only political party that has championed the bill. Given its past record on Hindu issues, one can not rule out this being an electoral gimmick, which would appear to be the case if it does not at least table it in the Rajya Sabha in the remaining time before the polls. Nonetheless, thus far, BJP comes across Godsend, in comparison to the baseline of other political parties like Congress, TMC and CPIM, who have opposed the bill; the treason of the last two crosses all limits in that still they get most of their seats and votes from West Bengal. TMC comes across the worst of the lot in that it asked for Citizenship Amendment Bill without Bangladesh- so although it is the ruling party of West Bengal, a large percentage of whose voters are of East Bengal origin, it seeks to damn only the Hindu Bengali segment of refugees seeking to escape religious persecution. If BJP highlights just this issue in West Bengal, it would be positioned for a leap forward in its electoral fortune in West Bengal, in due course, an electoral fortune that is on an upswing going by the recent local polls. What is, however, confounding is that BJP-RSS seems to be determined to muddy the choice for its Hindu Bengali prospective voters by having its ecosystem promote part of the disinformation campaign against bill in general and the Hindu Bengali refugees in particular. We document this strange phenomenon as well. This is particularly mindless since BJP-RSS has a reputation of being anti-Bengali, and with substantial basis as our documentation of the anti-Bengali hate discourse in its ecosystem reveals [11], [12], [13], [14]. In this article too, we show that there has been a significant amount of double talk by the ecosystem of the BJP and their readiness to throw the Hindus of East Bengal under the bus. This reputation has thus far blocked its progress in West Bengal. If it continues with this bill, with sincerity, it has the prospect of annulling this reputation for foreseeable future. But that promise is contingent on its leadership ruthlessly removing from its patronage the ethnic hate crowd, and visibly so. It remains to be seen if the top leadership has this foresight and authority.

Section C: A Demographic Necessity – The Hindu Refugees from East Bengal through facts and figures

A disinformation campaign has been launched that rather than West Bengal, it has been the North East that has borne the lion-share of the refugees from East Bengal, which has displaced the “indigenous’’ people and has altered the demographics therein. We examine the truth of these claims.

We start with by providing the exact numbers of Bengalis in Nagaland, Mizoram, Meghalaya and Manipur, from the Census of India, 2001 [7], which would show that by and large they have not taken in Hindu Bengali refugees. Manipur had a total of 27,100 Bengali speakers [both Hindu and Muslim], while the total population of Manipur was 21.66 lakhs. In short, the Bengalis were just over 1% of the total population of Manipur. Nagaland had a total of 58,890 Bengali speakers [again both Hindu and Muslim], out of a total population of 19.98 lakhs The Bengalis constituted less than 3% of the total population. Mizoram had 13,325 Bengali speakers out of a total population of 8.89 lakhs. In short, Mizoram had a total of 1.5% Bengali speakers [both Hindu and Muslim]. In Meghalaya, there were 1.5 lakh Bengali speakers [most of these would be Muslim, given the rising Muslim population in the western part of Meghalaya] out of a total of 23.19 lakhs. In short, the Bengali speakers are 6.14%. Yet, segments of the polity of these states have been protesting the Citizenship Amendment bill.

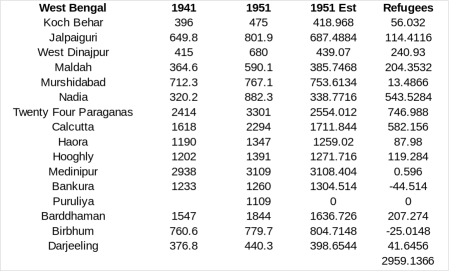

The three states that have taken in considerable number of Hindu Bengali refugees are West Bengal, Assam and Tripura. We focus on these states. First, we reproduce the Government of India figures on Hindu refugees from East Bengal up to the year 1970 pp. 18-19, [10], which Joya Chatterji has reproduced p. 112, [2]:

Thus the Government of India figures show that 52.83 lakhs of Hindu Bengali refugees arrived until 1970 with West Bengal taking about 39.56 lakhs, i.e., 74.88%, while 12.97 lakh refugees have settled outside West Bengal.

The Government of India figures are however quite conservative, as Joya Chatterji remarks, “No one knows precisely how many refugees went to India from East Bengal during this phase [partition]. The official, and improbably conservative, estimate for the period of eighteen years from 1946-1964 places the total at just under 5 million [50 lakhs], pp. 15-17, [10]. During these years, Hindus left East Bengal in successive waves and settled in West Bengal or the neighboring states of Assam and Tripura. The vast majority – three in four refugee families went to West Bengal. One in ten settled in Tripura, and slightly more, about 13 per cent, went to Assam. Only 2 percent settled in other parts of India. These refugees were predominantly Hindu Bengalis from East Bengal. A relatively small number were Hindus, again mainly Bengalis, from Sylhet, formerly a part of Assam, and most of them went to Assam and Tripura, which were the parts of India closest to where they came from. In addition, a few refugees from the Chittagong Hill Tracts, mainly Chakma tribal people, drifted into India, particularly into what is now the state of Arunachal Pradesh’’ pp. 105-106 , [2].

We estimate the number of Hindu Bengali refugees using growth rates of Hindus obtained from Census. Our estimates suggest that until 1971, 62.36 lakh refugees migrated to West Bengal from East Bengal, which was then East Pakistan, and 14.83 lakhs to Assam and 4.76 lakhs to Tripura. Thus, the Government of India figures were indeed extremely conservative. Given how minuscule percentage of the overall population the Hindu Bengali refugees constituted in the rest of India, Census would not give any numbers on them. Thus, per our estimate, 76.1% of the Hindu Bengali refugees went to West Bengal, which is consistent with Joya Chatterji’s observation; 18.1% went to Assam and 5.8% to Tripura. The percentages for Assam and Tripura in the above vary somewhat from those of Joya Chatterji, which may be attributed to our not being able to estimate the percentage that went to elsewhere in India, estimation errors in the Government sources that Joya Chatterji indicates, and certain inaccuracies inherent with the application of growth rates. Nonetheless, even these divergences are minor in terms of absolute numbers.

We also estimate that, just by 1981, the total number of Indic refugees and and Indic economic migrants who had come into West Bengal from the neighbouring states and Bangladesh stood at 1 crore and four lakhs people. Assuming that only 75 percent of these are actual refugees, one still sees around 80 lakh refugees that West Bengal has taken in, or roughly 11.86% of her total population. Per GoI figures, by 1973, West Bengal had 6 million refugees, which was 13.64% of the total population of 44 millions p. 151, [2]. We estimate that that there is a total of 25.82 lakh Hindu migrants into Assam from 1947 onwards, and assuming that there are 75% refugees here, it shows about 19.4 lakhs Hindu Bengali refugees. In Assam, the population in 1991 was 2.24 crores, which shows a population of 8.8% as refugees. In Tripura, there was about 5 lakh migrants. Considering all the migrants in Tripura to be Hindu Bengali refugees, 76.63 % of the overall Hindu Bengali refugees have been taken by West Bengal, 18.58% by Assam and about 5 % by Tripura. The intakes are consistent with the history of habitation of Hindu Bengalis before 1947 in that they comprised substantial percentages of both Assam and Tripura even before 1947. In particular, 40-50 % of the populace of Tripura used to be Bengalis even before 1947. And, the Hindu Bengali refugees primarily settled in the Barak valley, which used to be predominantly Bengali even before 1947, and other districts of Assam which had substantial Hindu Bengali population share even before 1947.

Specifics from GoI figures that we reproduce in Sections C.1-C.3, as also our Census based calculations therein, would show that since the lion’s share of Hindu Bengali refugees migrated to West Bengal from East Bengal after 1947, they have in fact altered the demographics of several districts of West Bengal, rather than that of Assam and Tripura. In C.4 we present demographic data about the Nepali populace in West Bengal and the North East, and postulate why there is no agitation against them, despite their considerable presence throughout.

It is pertinent to bear in mind that Hindu Bengalis, or any other Hindu segment can not be held responsible for partition. We have argued in the previous Section that Hindu masses had opposed partition throughout India, including in Bengal. Partition was decided by the British and in connivance with Congress, Muslim League, Indic big business, in accordance with the popular support for it among the Muslim masses. Hindu Bengali leadership was excluded from the decision making process concerning partition. As historian Leonard Gordon has stated, “One salient feature of the Mission and subsequent political and constitutional discussions from the Bengal point of view is that during all these talks in 1946 and then again in 1947, no Bengali leader was an insider or important figure in them. Although Sarat Bose was shortly added to the Congress Working Committee, there was no Bengali among the leading spokesmen of either the Congress or the Muslim League.’’ pp. 563-564, [30]. Medha Kudaisya who had written a biography of G. D. Birla after perusing his private papers, have documented how Vallabhbhai Patel, Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajagopalachari, and Indic business magnates like G. D. Birla had effected partition from the Indic side pp. 227, 228, 231, 232-240, 242, 248, 249, [51]. We also learn from Kudaisya that Birla suffered from a “Bengali-phobia’. In his view, [undivided] Bengal had “48 % destructive minded Hindus and 52% fanatic Muslims’’ (thus, in effect, all Hindu Bengalis were “destructive minded’’ in his view) and “He had begun to feel that, in any case, the Bengali Hindu was definitely unfriendly towards Marwari business’’ p. 240, [51]. Thus, the burden of the Hindu refugees from Pakistan and Bangladesh must be squarely borne by the entire Indian nation.

Section C.1: Hindu Bengali refugee numbers in West Bengal – A census growth rate estimate

In West Bengal, for the 1941-1951 decade, the numbers have to be tentative since the region was devastated by the massive Bengal Famine that claimed [depending on the source] between 20 and 40 lakh victims. Further, the epidemics that raged the region in the wake of the Bengal famine in 1943-46 took an uncounted number of victims. The situation is further muddied by the mass migrations from East Bengal in the wake of the partition. Joya Chatterji agrees with our point that the 1941 census was “flawed and inaccurate”. She remarks, “By 1947, after the war and famine had caused havoc to Bengal’s population, all inmates are unavoidably insecure. At best they provide rough orders of magnitude…” p. 107, [2]. Consequently, we have chosen Medinipur, which had not yet received any large number of refugees after 1947 as the district on which we can base the 1941-1951 Indic growth on. In short, we have assumed that the natural growth rate of the Indics in Bengal is best represented by the Indic growth rate of Medinipur district. Indics in Medinipur grew by 5.8%. The number of refugees and economic migrants for each district was estimated by taking the actual Indic numbers in the district in 1951, obtaining the estimated number for the district using the Indic numbers in 1941 and the Indic growth rate of Medinipur district and the subtracting this estimated number from the actual numbers. All the Indic numbers for the census between 1941 and 1991 in this and the subsequent sections are taken from pp. 279-282, [1]

It shows that the total number [in thousands] of refugees in each of the districts. This, as we mentioned, is only a rough estimate. The district of Puruliya did not exist in 1941 and was created in 1951, so we cannot estimate its numbers. Consequently, its refugee or economic migrant influx has been assumed to be zero. The growth rate of Bankura and Birbhum are lower than Medinipur and also, there was some influx from these regions into Calcutta and the Twenty Four Paraganas region due to the war and famine. So, they have a negative number, which has been faithfully counted as negative. The small number of Medinipur is due to the truncation of the decimals past the third decimal and is an artefact.

We obtain the total number of refugees and economic migrants as 29.59 lakhs. The number of refugees given by government sources vary from 20.99 lakhs (given in Census 1951), 23.66 lakhs (Indian Government), 25.1 lakhs (West Bengal Government) pp. 112, 119, 130 [2]. The last figure computed by the West Bengal state is the closest to ours. As per the Census of 1951, most of the refugees from East Bengal ended up in just three districts of West Bengal, the 24 Parganas, Calcutta and Nadia. In 1951, Census recorded 2,099,000 refugees, about 2/3 went to these 3 districts: 5.27, 4.33, 4.27 lakhs was the split respectively. West Dinajpur (1.15 lakhs), Cooch Behar (1 lakh), Jalpaiguri (0.99 lakhs) and Burdwan (0.96 lakhs) absorbed most of the remaining third. In decreasing order, the rest went to Howrah, Malda, Murshidabad, Hooghly, Midnapore, Darjeeling, Bankura, Birbhum pp. 119, 120, [2]. Per our estimate, the largest number of refugees also went to the 24 Parganas, Calcutta and Nadia, and in that order, though our estimates are higher, as is expected given how conservative the Government of India figures were.

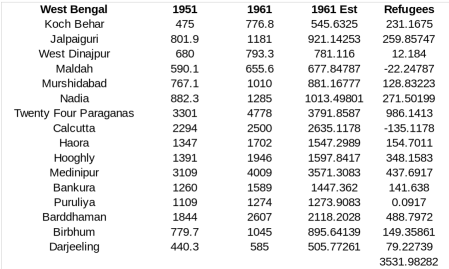

For the decades of 1951-1961, 1961-1971 and 1971 to 1981, the Indic growth rate of Puruliya was assumed to be the base. Puruliya being a tribal heavy district has fairly high growth, has seen very little conversion, and also, has received very few refugees or economic migrants. Using this as a base, we compute the number of Indic refugees for the decades of 1951-1961, 1961-1971 and 1971-1981. We stopped at this point, as there has been very little accusation of change of Indian demography past this point.

The 1951-1961 decade saw the ingress of a significant number of economic migrants into West Bengal too, especially from the neighbouring regions of Bihar and [today’s] Jharkhand. Consequently, not all the above migration are refugees from Bangladesh. The Government of India pegs the number of Hindu refugees to West Bengal between 1951-1961 to below 10 lakhs p. 112, [2], which however is extremely conservative. Based on the Government estimate, Joya Chatterji states that by 1961 there were over 30 lakh refugees in West Bengal, they were in the same parts of the province as in 1951 pp. 119-120, [2], and that between 1947 and 1961 close to 10 lakhs refugees settled in Cooch Behar, West Dinajpur, Murshidabad, Nadia p. 124, [2]. Our estimates of course provide a much larger cumulative number.

Owing to the massive 1964 riots in East Pakistan, the 1961-1971 decade saw the immigration of another huge wave of refugee influx into West Bengal; we estimate the number as 18.25 lakhs. The actual number of refugees is probably even higher than this, due to the fact that the first beginnings of family planning was already beginning to be seen among the middle class of Bengali society, especially Calcutta and the urban areas around it. The Governments of India and West Bengal pegs this number to again below 10 lakhs pp. 112, 130 [2], which is extremely conservative. This decade didn’t see a huge economic immigration into Bengal.

The 1971 genocide of Hindus by the Pakistani army in the run up to the Bangladesh war and the massive seizures of Hindu properties in Bangladesh in the 1970s sent colossal numbers of Hindus fleeing into West Bengal. This number is at 23.69 lakhs. Based on the Government of West Bengal figures p. 120, [46] Joya Chatterji writes, “In 1973, surveys of refugees showed that their numbers had doubled in the previous decade and now constituted more than 6 million [60 lakhs], but that the patterns of settlement remained the same as they had been in 1951 and in 1961’’ p. 120, [2]

Thus, just by 1981, the total number of refugees and economic migrants who had come into Bengal from the neighbouring states and Bangladesh stood at 1 crore and four lakhs people. Assuming that only 75 percent of these are actual refugees, one still sees around 80 lakh refugees that Bengal has taken in, or roughly 11.86% of her total population. Per GoI figures, by 1973, West Bengal had 6 million refugees, which was 13.64% of the total population of 44 millions p. 151 [2].

Neither we nor the GoI figures have factored in the descendants of the refugees. Joya Chatterji rightly notes, “The huge increase in West Bengal’s urban population after partition was not simply the direct result of ‘adding on’ the 5 or 6 million Hindus who came from East Bengal. The refugee influx caused the population of the province to increase geometrically. It caused the number of females in West Bengal to rise dramatically in the ten years from 1941 to 1951, reversing the decline of the previous 40 years. This change was particularly remarkable in the towns and cities of West Bengal, and nowhere more so than in Calcutta.’’ p. 155 [2] Specifically, in 1901, female-male ratio was 518-1000, in 1941 it was 456-1000, in Calcutta. By 1951, the ratio had become 580-1000, by 1961, 612-1000, p. 155, [2], Between 1951-56, the birth-rate among refugees grew at a rate 60% faster than that of the host population, as a consequence of more women in wedlock living permanently with their husbands in the city pp. 149-150, [2].

Even the substantially conservative Government figures capture the impact of this magnitude of influx. We reproduce Joya Chatterji’s summary of the GoI figures: “As the census superintendent observed in 1951, ‘the effect of this influx, amounting to fifty years’ normal [population] growth of the state packed into five years, [had] been one of painful swarming ; in certain areas it had increased the density per square mile by several thousands, in others by several hundreds and over West Bengal as a whole be 68. The impact was greatest in those areas where refugees clustered, in Calcutta itself, the 24 Parganas and Nadia, where refugees took over all the empty space in and around the big towns. Calcutta, as we have seen, was welded together into a single, gigantic metropolis, surrounded by vast, sprawling suburbs. Nadia, too, was similarly transformed. Before partition, the population of Nadia had been in decline, yet by 1951 it had witnessed the most rapid growth in population of any district in West Bengal, ‘entirely due to the influx of the displaced population [in one decade, Nadia’s population grew by 36.3%]. Its formerly small and sleepy townships such as Ranaghat, Chakdah and Nabadwip witnessed a growth in population which was little short of spectacular. By 1961, Nabadwip’s population had achieved a staggeringly high density of 16000 people per square mile [1961 Census]. In the 24 Parganas, the thanas of Basirhat, Habra, Barasat, Baruipur and Hasnabad all ‘witnessed a phenomenal growth after the partition of 1947.’ [1961 Census]. By 1961, the 24 Parganas had a population of over 6.2 million and had become the most populous District in the whole of India. Most towns and cities of West Bengal grew by leaps and bounds. By 1961, West Bengal had four times as many towns with a population over 100,000 than it had in 1941. During the same two decades, the number of towns with between 50000 and 100000 inhabitants virtually doubled. This rapid, unplanned and unprecedented explosion in the rate of Bengal’s urbanization was caused, in the main, by the influx of refugees pp. 154-155, [2]

Per GoI figures by 1973, in towns of West Bengal 25% of the populace were refugees p. 151, [2] And since partition there has been a sudden spurt in urban population, as the following table produced in p. 155, [2] from the Census figures in [47], reveal.

Number of towns in each class, West Bengal, 1901-1961

I – 100,000 or above

II- 50,000-99,999

III- 20,000-49,999

IV-10,000-19,999

V-5000-9999

VI-Less than 5000

Between 1947-1961, the population of West Bengal grew from just over 20 million to almost 35 million. During 1951-61, India’s population increased by 21.5%, that of West Bengal, almost 33% p. 155, [2] Thus, a province already overcrowded in 1947, by 1961, more than 1000 people lived in West Bengal per square mile. Calcutta became the most densely populated place in earth. By 1961, almost 9 million people, which is no less than the quarter of the populace of West Bengal lived in towns or cities p. 156, [2].

So, one state in which the Hindu Bengali refugees actually altered the demographics is West Bengal!

Section C.2: The Hindu Bengali refugees in Assam – A story in numbers and geography

Section C.2.1: The Census growth rate estimate

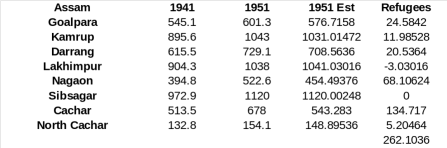

Assam has seen a large number of refugees coming in from East Bengal, so let us quantify the total number of refugees that she has taken. For this purpose, we utilise the Indic growth rate of Sibsagar for computing the natural Indic growth rates of the Brahmaputra valley, and the Indic growth rate of Puruliya for computing the natural growth rates of Barak valley [Cachar], which is dominated by the Bengalis. For 1941-1951 decade, we used the Indic growth rates in Medinipur, since Cachar was also at the fag end of those hit by the Bengal famine. The source for all the statistics is pp. 199-202, [1].

In the aftermath of the Partition, in the 1951 census, the total number of refugees and economic migrants in Assam was found to be around 2.62 lakhs. Out of the 2.62 lakhs, the number of refugees in Cachar was found to be 1.37 lakhs, which shows that the early refugees from Bangladesh mostly came there. This is only natural, given that Sylhet district, which was split, saw the Hindu refugees spill over mostly into the Indian part of Sylhet [which was merged into the then Cachar district]. The estimated statistics are also in harmony with what is found on the ground.

It was between 1951 and 1961 that Assam saw the highest influx of East Bengali refugees and also the Nepalis in the Brahmaputra valley, which coincides with the rise of the anti-Bengali sentiment in Assam. The total number of migrants, both refugees and economic migrants included, was 5.84 lakhs. This included significant immigration of Nepalis to the district of Darrang, and people from the Hindi belt to the districts of Lakhimpur and North Cachar.

The 1971 genocide of Hindus by the Pakistani army in the run up to the Bangladesh war and the massive seizures of Hindu properties in Bangladesh in the 1970s sent colossal numbers of Hindus fleeing into Assam (along with into both West Bengal and Tripura). This was the precursor to the Asom Andolan. The number of refugees (and economic migrants) was around 11.32 lakhs. The refugees, this time fleeing in a panic, came into all the regions of Assam.

Note that even in the wake of the genocide of the Hindu Bengalis in East Pakistan in 1971, the number of Hindu Bengali refugees fleeing into Assam is half that of the number that fled into West Bengal per our estimates. We have calculated the refugees who continued to live in West Bengal and Assam even after the formation of Bangladesh. The influx prior to the 1971 war, in the wake of the genocide, was far greater, in West Bengal, much more than elsewhere. As Gary Bass has noted, “ The raging civil war [in 1971 East Pakistan] sent fresh droves of refugees fleeing into India. …This was a disaster for the destitute border states – above all for West Bengal. The state was by far the hardest hit. In July 1971, India hosted six and a half million refugees, over five million of them in West Bengal, which contained 419 out of the 593 refugee camps in India. Over a million and a half of the refugees had spilled outside of the camps into the rest of the state. There were hordes of refugees in Calcutta itself, with thousands dug in around the city’s airport.’’ Loc 4117, [15] Ajoy Mukherjee, the chief minister of West Bengal wrote in June, 1971, “West Bengal today is deluged with millions of victims of Pakistan’s oppression” Loc 4120-4123, [15] Bass has further noted, “The Indian foreign ministry accused Pakistan of intentionally “fomenting tensions between Hindus and Muslims in West Bengal, between Bengali refugees and Assamese in Assam, between tribals (mostly Christians) and Bengali refugees in Meghalaya and creating a situation of near suffocation in Tripura where the number of refugees (over 1 million) is more than two thirds of the original population of 1.5 million’’ Loc 4157-4160, [15]. Note however that despite the deluge being the most significant in West Bengal there never was any intra-Hindu conflict there.

Finally, in the 1971-1991 decades [there was no census in Assam in 1981, due to the disturbed conditions prevailing in the valley], the number of refugees from Bangladesh, especially in the mid-late 1970s, was huge. The total number of migrants was found to be around 6.04 lakhs, with a large number of them settling in the Brahmaputra valley too. However, there is a vital point to be observed. The number of Hindu Bengali refugees in Hindu-Bengali majority regions of Assam is actually higher than what our numbers reveal. This is because of the following two reasons. 1) Given the anti-Bengali feeling in Assam, there has been a significant emigration of the educated elites out of the Cachar region to greener pastures. 2) The tribal Indic growth rates of Puruliya is greater than that of the Hindu Bengalis, but we apply the former on the Hindu Bengali dominant districts to calculate the number of refugees therein.

Adding the total numbers, it turns out that there is a total of 25.82 lakhs, and assuming that there are 75% refugees here, it shows about 19.4 lakhs Hindu Bengali refugees. In Assam, the population in 1991 was 2.24 crores, which shows a population of 8.8% as refugees.

Section C.2.2: Have the Hindu Bengali refugees altered the linguistic demography anywhere in Assam?

First, it is stated that the Assamese speakers have become minority in Assam owing to the influx of Bengali migrants since 1947. The truth is that they constituted a minority in Assam long before 1947. In 1931, not even the Brahmaputra valley, leave alone the whole state, that, then, included even Sylhet, was Asomiya majority. In 1931, the total number of Asomiya speakers in the Brahmaputra valley [comprised of today’s Brahmaputra valley of Assam and Arunachal Pradesh, but not Nagaland or Meghalaya] was 41.97% p. 184, [5]. Indeed, in the entire state as a whole, the percentage of Asomiya speakers was 21.57%, with the Bengali speakers constituting 42.89% p. 184, [5]. Thus, Assam was never constituted on linguistic basis, and the influx of the Hindu Bengali refugees since partition have not reduced the Asomiya speakers to minority.

Second, it has been bandied about that the Barak valley (Cachar) was not Bengali and that the Bengalis there are settlers. To examine this question, we consider the first census held in 1872. This is what Major Stewart, who estimated the population in the region, had observed. He pointed out that the total population of the district was 2.2 lakhs, of which 1.3 lakhs was Bengali [both Hindu and Muslim, put together] p. 377, [4]. The census of 1901, often regarded as the first proper census, further clarifies this point. In 1901, a total of 61.49% of the total population returned their mother tongue as Bangla. p. 94, [5]. The same is reflected in the census of 1931, which showed that 62.8% of the total population as speaking Bangla p. 184, [6]. Further, Goalpara, at the western end of the Brahmaputra valley also showed that 69.26% of the total population returned their mother tongue as Bangla p. 94, [5]. The 1931 Census 1931 also show that 53.97% of Goalpara spoke Bangla p. 184, [6].

We now examine the number of Hindu refugees until 1991 by division in Assam based on our previous calculations. We assumed that 75% of the increase of Indics was due to refugees from East Pakistan in the Brahmaputra valley. In Cachar, we assumed that 100% of the immigration was due to the refugees from East Pakistan.

It can be observed from the above table that Hindu refugees constitute less than 10% of the population in all the districts of the Brahmaputra and the Barak valleys. And, not all Hindu refugees are Bengalis either. For example, a large proportion of the influx into Goalpara and Kamrup in particular is not due to the Bengali Hindus. It is due to the immigration of the Koch, Rabha, Hajong and other tribal populations that were left on the East Pakistan side of the border and who fled after partition into Assam to reunite with their brethren there. Thus, Hindu Bengali refugees have not altered the demographics anywhere in Assam, except possibly North Cachar Hills which we discuss next.

We examine the Bengali speaking populace in North Cachar Hills, since it shows an migrant population of 27%. In the census of 2001, it shows the number of Bengali speakers [both Hindu and Muslim] at 1.24 lakhs. Thus, at most the Hindu Bengali refugees constitute 15% of the populace in the district. In reality, their percentage is far less. This is because there were 3.33% Bengali native speakers in North Cachar Hills in the 1931 census p. 184, [6], and the normal growth rate applied to them would imply a substantial part of the 1.24 lakh Bengali speaking populace is not refugee, and not all the Bengalis of the 1.24 lakh Bengali speaking populace are Hindus either.

Next, clearly 12% of the populace comprises of Hindu migrants who do not speak Bengali – in other words they would be Hindi and Nepali speakers, or constitute internal migration within Assam itself, all of whom would be economic migrants.

Section C.2.3: Will citizenship to Bengali Refugees after 1971 really change demographics of Assam?

The Assam accord agrees to consider all Hindu Bengalis who migrated to Assam up to 1971 as citizens of Assam. Citizenship Amendment Bill seeks to additionally provide citizenship to the Hindu Bengalis who migrated to Assam from Bangladesh between 1971 to 2016. We examine if this would alter the demographics of Assam.

Previously, we estimated the number of refugees in Assam using the Sibsagar’s rate of Indic growth as the natural growth rate of the Indics. This amounted to a grand total of 6.04 lakh Hindu refugees in the period between 1971 and 1991. In this section, we shall further try to examine how many Indic refugees are in Assam using the Indic growth rate between 1941 and 1951 as the base growth rate for the 1971-1991 period. The number of Indic refugees coming to Assam after 1991 is extremely small, so we shall focus on the 1971-1991 period and then examine where in Assam they are present. Using the 1941-1951 Indic growth rate of Sibsagar gives an upper bound on the number of Indic refugees, since the natural growth of Indics in the 1971-1991 period is much higher than the natural growth of the Indics in 1941-1951 decade, even given the immigration of Hindus, both as refugees from East Bengal and economic migrants from other parts of India.

Assuming that 80% of the higher growth is due to refugees, we get 9.52 lakh refugees in 1991 [this, by the way, is a ridiculously high estimate, given that both Cachar Hills and Darrang have seen significant immigration of Hindi speaking people and Nepali speaking people respectively in the period in question and the growth rates assumed are extremely low]. Assuming that the refugees have grown by the same fractions that other Hindus have in Assam, one gets a total of 12.04 lakhs. This, we emphasise is the upper limits of the number of refugees that have found refuge in Assam. This constitutes a grand total of <4% of the population. For a comparison, the number of Hindi speakers in Karnataka and Andhra has grown by a similar percentage since 1971.

Section C.2.4: Why retaining Hindu Bengalis is a demographic necessity for Assam?

Outside the Barak valley, which is predominantly Bengali and has always been predominantly Bengali since the first census in 1872, the significant concentrations of Bengali speakers are left in Kokrajhar, Dhubri, Goalpara, Bongaigaon, Barpeta, Kamrup, Darrang, Morigaon, and Nagaon. We emphasise that all these districts are either Hindu minority, or fast losing Hindus. The Hindu Bengali refugees constitute 8.1% in Goalpara, 8.25% in Nagaon and 7.78% in Cachar. All these districts are less than 60% Hindu already. In the case of Goalpara and Nagaon, Hindus are already a minority in the divisions, while in Cachar, Hindus are just a shade above 50%. Further, in Kamrup and Darrang, Indics constitute 61.1% and 64.5% of the total populations. To consider expelling the Bengali Hindus from these areas would be to hand over the regions to the illegal Bangladeshi Muslims, who number anywhere between 20 and 30 lakhs. Hindus of Assam were 50.68% in 0-4 age group, and 61.88% overall, according to the 2011 census. By expelling Bengali Hindus, Asomiya will make themselves more vulnerable in terms of religious demography. It is quite likely that this was the reference that Himanta Biswa Sarma had, when he remarked that he accepted the `Hindu side’ of Jinnah’s legacy in his fight for the Citizenship Amendment Bill.

These numbers also explain why the anti-Bengali violence has been mostly confined to the upper regions of Assam [with the exception of Kamrup, which, being the capital district, has seen repercussions of the anti-Bengali violence elsewhere], where they constitute a miniscule minority. Both the Silapathar massacre [Lakhimpur, Upper Assam] and the Khoirabari massacre [Darrang, Upper Assam] ocurred in areas where the Hindus were overall an overwhelming majority at the time of the massacre, and both occurred in Upper Assam. Lower Assam and regions south of the Brahmaputra have not seen any significant anti-Bengali Hindu violence since the Partition, because the Hindus tend to converge and resist the Muslims of the region, who are either a majority or a large minority in all the districts of lower Assam. This phenomenon is further true even of the erstwhile Nagaon [current Nagaon, Morigaon and Hojai districts], where the Hindu Bengalis constitute a significant minority. Himanta Biswa Sarma pointed out that he was supported by the Hindus of Goalpara, Barpeta, etc in his quest for the Citizenship Amendment Bill. He is also a cynical politician who prioritizes his shot at power above all civilizational and moral goals. Thus, the fact that he has been vocally supporting the Citizenship Amendment Bill suggests that his vote base, that is, the Hindus (both Asomiyas and Bengalis) of Lower Assam support the bill. The strident opposition to the bill appears to emerge from the Muslims and a small but vocal group of Hindu Asomiyas driven by linguistic chauvinism or even incentivized collusion with Islamists.