This is a powerful book which is surely going to set the cat amongst the pigeons. The author questions Christianity as an organised religion sharply; and the readers would want a scholarly counterview by Christian scholars. The author is the daughter of an English monk and a nun, which makes the book a little more interesting. She is presently a journalist at The Times.

This is a book about the savage Christian destruction of the classical Greco-Roman world. From AD 312, when Constantine started ruling Rome, to AD 529 under the rule of Justinian, the crushing of the pagan world was near total. Only one percent of Latin literature survived the centuries. The author says, ‘A great deal was achieved by the blunt weapons of indifference and sheer stupidity.’ The fast-paced narrative tells the story of Christian conversion of the pagan world sweeping across Egypt, Rome, northern Turkey, Bithynia, Syria, and in the end to Athens- the city where Western philosophy really began and where, in AD 529, it ended.

Paganism is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for populations who practiced polytheism. The alternate terms were hellene, gentile, and heathen. It was a derogatory term for the polytheistic groups implying their inferiority in believing false gods.

Roman Emperors and the Transition to Christianity

If we were to believe Hollywood, then Nero was the cruellest devil exclusively targeting the Christians. However, Nero was cruel to all irrespective of their religion, says the author. He indeed blamed the Christians for starting the fire in Rome in AD 64. Tacitus described a ‘pernicious superstition’, a new cult which had recently arrived in Rome. The followers of this superstition were the troublesome adherents of a man called ‘Christus’. Tacitus said that governor Pontius Pilate executed Christus when Tiberius held power. This is, in fact, the sole mention of the momentous event in a non-Christian source of that period.

By the time of the Great Fire of Rome, a few Christians were already living in Rome. Nero executed and killed a sizable number of Christians in a brutal manner which shocked the Romans too. This was the first imperial persecution of the Christians. But the author argues that the Romans did not seek to wipe Christianity out. If they had, they would have certainly succeeded.

Pliny, as the Roman governor of Bithynia-Pontus (now in modern Turkey), wrote a letter to Emperor Trajan around 112 AD and asked for counsel on dealing with Christians. In the letter, Pliny asks guidance on how to conduct legal trials of suspected Christians appearing before him for anonymous accusations, which he had never done before. Pliny saved copies of his letters and Trajan’s replies too; and these are the earliest surviving Roman documents referring to early Christians.

Trajan’s response to Pliny makes it clear that being a Christian was enough for punishment; but clearer too in not tracking down Christians and by also ignoring anonymous denunciations. The correspondence between Pliny and Emperor Trajan shows that the Roman Empire, as a government entity, did not think of “seeking out” Christians for prosecution or persecution. Hence, the famous first recorded encounter between Christians and Romans does not document a clash of religious ideals: it is about law and order. It was Pliny the Younger’s duty as a governor, and as a Roman, to monitor and minimize discontent.

Pliny describes Christianity as nothing more than a cult carried to extreme lengths. For a long time, Romans struggled to understand why Christians could not simply add the worship of this new Christian god to the old ones. Many Romans did not like the Christians and their attitudes towards the existing customs and gods.

But for the first 250 years after the birth of Christ, the imperial policy towards them was first to ignore them and then to declare of not hounding them as the letter from Emperor Trajan to Pliny clearly states. The author says that this was a grace and liberty that the Christians would decline to show to other religions when they finally gained control.

The Key Event of Constantine’s Conversion

In October AD 312, emperor Constantine converted to Christianity following a vision of a cross of light from above the Sun with the words next to it: ‘Conquer by this.’ And thus, started a mass movement of swift conversions by the rulers themselves using their armies. Christian history looks at him with respect, but the non-Christians looked at him less fondly. There were rumours that Constantine converted to absolve himself of the guilt of murdering his wife. The author however says that the dates do not match. Constantine had embraced Christianity long before he killed his wife.

Constantine gained control over the whole empire in AD 324 and decrees then followed disbarring non-Christians from moving into plum positions, banning idolatry, ordering mass buildings, and expanding Churches to remove the ‘polytheistic madness.’ In AD 356, it became illegal-on pain of death-to worship images even as pagans became ‘madmen’. Christian writers welcomed the destruction and egged their rulers for greater acts of violence. After a brief respite, rulings picked up again in the 380s and the 390s with increasing rapidity and ferocity against all non-Christian ritual.

The Church, till so recently persecuted, suddenly flowed in money. Tax relief to Churches, handsome gifts and salaries, astonishing constructions followed in the aftermath of Constantine’s conversion. Unfortunately, the money came from the pagan temples. From the 330s onwards, there was removal of some of the most sacred and most valuable objects in acts of gross violations to the sacred belief systems and faith. The history of Greco-Roman culture stretched back at least a thousand years into pre-history. And it all came crumbling down in a remarkably short span.

Julian was the last non-Christian Roman Emperor from 361 to 363. He was also a philosopher and author in Greek. His rejection of Christianity, and his promotion of Neoplatonic Hellenism in its place, made the church promptly call him as Julian the Apostate. When the emperor Julian pointedly avoided executing Christians in his brief reign, one writer far from being grateful recorded that Julian had begrudged the honour of martyrdom to combatants. A little over a century after Constantine, in AD 423, the Christian government announced that any pagans who still survived needed suppression, and said ominously, ‘We now believe that there are none.’

Finally, a decree in AD 529 by Justinian (now known as law 1.11.10.2) where ‘the impious and wicked pagans were no longer allowed to continue their insane error’ became the deathblow to all paganism. The punishment for worshipping statues, offering sacrifice or even a baptized returning to older ways would be execution. Christianity became the official religion of the empire. There was a forcible closure of every ‘single road to error.’ This was the law which had incredible consequences. Athens, which was the last bastion of classical literature, fell. Scholars declared that the entirety of the barbarian invasions had been less damaging to Athenian philosophy than Christianity was. This law was also the beginning of the Dark Ages of the European continent according to some historians.

Christian Literature: Distortions, Martyrs, and Circumcellions

Christian literature would then go on to portray Roman Emperors and their officials as demonically possessed servants of Satan who hungered insatiably for Christian blood. Martyrs became popular in the Christian literature. The martyrdom tales though inspiring and entertaining however show contempt for historicity. The martyrs and martyrdoms exerted a powerful hold over European art for centuries. Now the thought is that only a few martyrdom tales from the early Church are reliable.

Imperial persecutions on Christians were fewer than thirteen in three whole centuries of Roman rule. They have however loomed large in Christian accounts dominating the narrative; but is at best misleading and at worst a gross misrepresentation, says the author. ‘Why were the Christians persecuted so little and so late?’ is a better question, she says. But these tales were very influential. GB Shaw observed a millennium later, ‘martyrdom is the only way a man can become famous without ability.’ More than that, in a socially unequal era it was the way in which women and even slaves may shine.

Christians deprived of execution and martyrdom were quite depressed, and some turned to suicide. Martyrdom was an instant ticket to eternal glory in heaven and eternal fame on Earth. The group most famous for practising this were known as ‘Circumcellions.’ They were bands of Christian extremists in North Africa in the early to mid-4th century, who regarded martyrdom as the true Christian virtue (as the early Church Father Tertullian said, ‘a martyr’s death day was actually his birthday’). They disagreed on the primacy of chastity, sobriety, humility, and charity. Instead, they focused on bringing about their own martyrdom.

On occasion, members of this group assaulted Roman legionaries or armed travellers with simple wooden clubs to provoke them into attacking and martyring them. Others interrupted courts of law and verbally provoked the judge so that he would order their immediate execution (a normal punishment at the time for contempt of court). However, there was more wanton violence on their part, including mutilations of priests and others the circumcellions considered unholy. Many of the targets of their attacks were in such a state as it would have made it impossible for them to retaliate and thus provide the martyrdom the circumcellions were seeking.

The sect survived until the fifth century in Northern Africa. Augustine wrote these people ‘lived as bandits, died as circumcellions, and honoured as martyrs.’ The Catholic Church appalled by their activities termed them heretical. They were initially concerned with remedying social grievances like condemning property and slavery, and advocating among other things, free love, and debt cancellation. However, they spiralled out of control later.

Demons and Discriminations in early Christianity

Demons became extremely popular in the literature during this conquest of Christianity. Modern historians pass over demonologies with an embarrassing silence; but demons obsessed some of the greatest minds of Early Christianity. The author says: ‘One consequence of the concept of demons was that wicked thoughts were the fault of the demon and not the man: an exculpatory quirk that meant even the most sinful thoughts could be admitted.’ Blame it on the devil.

A faithful Christian wrote an anxious letter to Augustine (13 November 354 – 28 August 430 AD). ‘May a Christian use baths which are used by pagans on feast day either while the pagans are there, or after they have left? May a Christian sit in a sedan chair if a pagan has sat in that same chair during the feast day celebrations of an ‘idol’? if a thirsty Christian comes across a well in a deserted temple, may they drink from it? If a Christian is starving and on the point of death, and they see food in an idol’s temple, may they eat it?’ The answer was better to reject it with Christian fortitude. If it is a choice between contamination with pagan objects and death, the Christian must unhesitatingly choose death.

The fathers of early Church turned their full rhetorical force on religious lapses. The other religions became sick, insane, evil, damned, inferior. It was cruelty to allow someone to follow a non-Christian path. To oppose another man’s religion was not wicked or intolerant, the clerics told their congregations. They were the most virtuous things a man might do.

The Destruction of Temples and Statues

The Bible itself demanded it. There is enough biblical justification for the persecution of non-believers. The Bible, as a generation of Christian authors declared, is clear on matters of idolatry. The Christians of the Roman Empire listened and as the fourth century wore on, they began to obey, as the author says.

Deuteronomy says: ‘A person indulging in this should be stoned to death.’ And if the whole city fell into such sin? The answer is: ‘Destruction is decreed.’ As the uncompromising words of Deuteronomy instructed: ‘And ye shall overthrow their altars, and break their pillars, and burn their groves with fire; and ye shall hew down the graven images of their gods and destroy the names of them out of that place.’ The followers obeyed this fully in a cruel period of destruction. There was destruction of the sacrificial gods in the idea that a religious system in which sacrifice was central would struggle to survive if there were nothing to sacrifice too.

Alexandria in Egypt was an impressive city filled with huge structures. Even Julius Caesar (100 BCE – 44 BCE) resolved to improve Rome after visiting this city. The city boasted of some of the finest architectural and academic achievements in the form of the Great Lighthouse, the Museum, the Great Library, and The Temple of Serapis. The last was the most beautiful of them all which became rubble in the year AD 392 under the orders of Theophilus, the newly appointed bishop of Alexandria.

There was destruction and removal of a vast number of works of the devil in the form of books, arts, sculpture, and sacred groves. The Parthenon Marbles of Greece, the basalt bust of Germanicus, a statue of Bacchus in Tuscany, Goddess Hera, the statute of Apollo from Salamis, the great statue of Athena at Palmyra are a few examples of the destruction of beautiful art and sculpture of that era by the hands of Christian zealots. The colossal statue of Athena in Athens, the sacred centrepiece was torn down in the fifth century AD. In many cities, people spontaneously destroyed the adjacent temples and statues and erected Churches without any command of the Emperor.

A recent book (Making and Breaking the Gods: Christian Responses to Pagan Sculpture in Late Antiquity by Troels Myrup Kristensen) on this destruction of statues focussing just on Egypt and the Near East runs to three hundred pages, dense with pictures of mutilation, says the author. Archaeologist Eberhard Sauer, a specialist in the archaeology of religious hatred, has well studied the cuts, mutilations, and destructions of the statutes. Some evidence remains but most is gone. Many statues vanished by getting pulverized, shattered, scattered, burned, or melted into absence. Some went down into rivers, sewers, and wells.

In Syria, the monks-fearless, rootless, fanatical-became infamous for their intensity and violence of their attacks on temples, statues, and monuments, and sometimes even the priests who opposed them.

Book Burning and Destruction of Libraries

The burning of books was part of the advent and imposition of Christianity, said one author. It was a terrifying act which converted many Alexandrians. Philosophers and poets fled the city in terror. One Greek professor wrote: ‘The dead used to leave the city alive behind them, but we, the living, now carry the city to her grave.’

The Temple of Serapis in Alexandria held a magnificent Library. Excavations in the 1940s uncovered nineteen uniform rooms where the books were most likely shelved. Thousands of volumes covering all topics from religion to mathematics existed. Serapis became a demon and not a wonder of art or a loved local God. The famous artworks, the lifelike statues, and the gold-plated wall standing for centuries (built by Ptolemy III reigning from 246–222 BCE) became rubble and later a church came up housing the relics of St John the Baptist. Christian chronicles called this a victory and non-Christian accounts call it an obvious tragedy. Of course, later Christian writers had their own story of the destruction, one of the most shameful incidents of attacking knowledge in ancient history.

‘Stay clear of all pagan books!’ declared one Apostolic Constitution. The Christian habit of book-burning went to enjoy a long history. Syrian Bishop Rabbula in the fifth century ordered, ‘Search out the books of the heretics in every place and whenever you can, either bring them to us, or burn them in fire.’ The assault on books was by censorship, intellectual hostility, and pure fear. The existence of a sacred text demanded this.

Things changed intellectually into what was in the Bible and what was everything else; what was right and what was wrong, in short. Argumentation and competition as a method of philosophy became a madness, the mother of evils and disease according to John Chrysostom. The Church viciously attacked atheism, science, and philosophy. An accusation of ‘magic’ was frequently the prelude to the spate of burnings. As with destructions of the temples, there was no shame in this. This was God’s good work and Christian hagiography hymned its virtue.

There were people like Ammianus and Libanius who burned their own works out of fear. Christianity had little interest in preserving philosophers who contradicted them and poets who described perverted acts or made satires on gods. There was overwriting of new texts on the works of many authors in alignment with Christian teachings. There was erasure of Pliny, Plautus, Cicero, Seneca, Virgil, Ovid, Lucan, Livy, and many more to make way for new texts. Over the next few centuries, the copying and preservation of classical literature completely made way for the Bible and copies of Augustine.

One preacher said,’ The writings of the Greeks have all perished and are obliterated. Where is Plato? Nowhere! Where Paul? In the mouths of all?’ There was a near destruction of all Latin and Greek literature by a combination of ignorance, fear, and idiocy. The estimates go that less than ten per cent of all classical literature has survived into the modern era. For Latin, it is worse; only one hundredth of its literature remains.

Filtering of the ‘Good’ from the ‘Bad’ of Pagan Literature and Ideas

Christianity did make some efforts to preserve literature and maintain libraries and it is an alluring image. It is, in fact, a far less glorious tale of tortured and beaten philosophers; of intellectuals setting their own libraries to fire out of fear. Literature lost its liberty and certain topics simply vanished from philosophical debate. The Church became a fierce filter on all written material over centuries. It became a ‘semi-permeable membrane’ allowing the writings of Christianity to pass through but not that of its enemies. Eusebius-the father of Christian history-declared that the job of the historian was not to record everything but instead only those things that would do a Christian good to read. Uncomfortable truths were not to be dwelt upon, he said.

Ovid, Homer, Martial, Catullus were all censored for improper works. The writings of John Chrysostom presented a list of terrible snares for the mind: fornification, lust, laughter, banter, dice, horse-racing, and the theatre. Philosophers who wished their works and careers to survive in this increasingly hostile world had to curb their teachings.

However, it was painfully obvious to the educated Christians that the intellectual achievements of the ‘insane pagans’ were vastly superior to their own. But it was impossible to embrace the satanic Greek and Roman literature; and Christianity was in a tricky situation. Gradually, from self-interest and partly from actual interest, Christianity started to absorb the literature of the ‘heathens’ into itself. Educated Romans and Greeks looked at the Bible with utter disdain and writers such as Augustine knew that. The old Bible was in a language which clearly showed God to be speaking in a common accent full of grammatical errors. It was embarrassing to say the least for the Christian writers. The high-class intellectuals were not impressed enough for conversion. Classical scholars had been reading Homer allegorically for centuries; and when better-read Christians started doing the same with the Bible, the critics called it a cowardly act.

Christian intellectuals struggled to fuse together the classical and the Christian. Bishop Ambrose dressed Cicero’s stoic principles into Christian cloths; while Augustine adopted Roman oratory for Christian ends. The philosophical terms of the Greeks started to make their way into Christian philosophy. The author says that it was strange that long dead thinkers who happened to have any resemblances to Christianity in their writings became unwitting ancestors in the tradition. Plato and Socrates became the Christians before Christ.

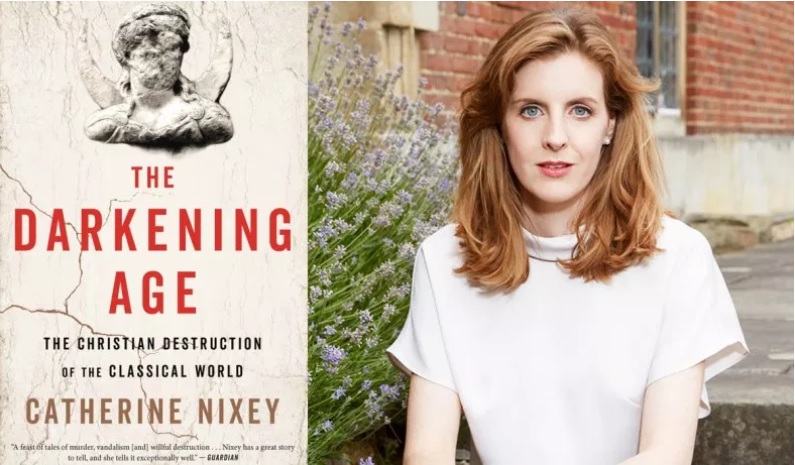

Featured Image: National Review