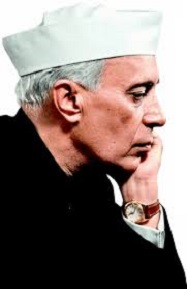

This is a review of the book, Nehru: A Troubled Legacy by R N P Singh, New Delhi: Wisdom Tree, 2015

The English historian, politician, and writer Lord John Dalberg-Acton wrote in an 1887 letter to Bishop Creighton, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men.”[1]

After reading R N P Singh’s painstakingly researched work on Nehru, perhaps one would be bold enough to say that Lord Acton’s words ring particularly true in the case of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, or as some have called him, India’s last Viceroy.

For seventeen years after Indian independence, Jawaharlal Nehru enjoyed indomitable supremacy over the government of India and over the Congress party. In spite of this (or perhaps because) he miserably failed both the country and his political party.

For seventeen years after Indian independence, Jawaharlal Nehru enjoyed indomitable supremacy over the government of India and over the Congress party. In spite of this (or perhaps because) he miserably failed both the country and his political party.

Greed for power, eagerness to promote his kin, a total mismatch between his speech and action, his vague understanding of socialism, his complete ignorance of the conditions of India’s poor, and his naiveté with regard to national security ensured that India continued limping long after it had removed the British shackles off its back.

All through his political life, Nehru was fortunate to have the backing of Gandhi. And Gandhi died before he could fully see the dark side of Nehru in power. Singh says in unambiguous words: “Whenever Nehru was in trouble, Gandhi came to his rescue.”[2]

For instance, speaking to the press in July 1929, Gandhi said, “Those who know the relations that subsist between Jawaharlal and me, know that his being in the chair is as good as my being in it.”[3]

Not only did Gandhi speak in favour of Nehru, he actively interceded on his behalf to bring him to power. During the 1946 election, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was in line for the post of Congress president since Nehru had already presided at Lucknow in 1936 and Faizpur in 1937. Twelve out of fifteen Provincial Congress Committees favoured Patel while only three favoured Nehru.

But Gandhi forcibly intervened. Patel was requested to step down. Nehru was elected.[4] If Gandhi had not thrust himself upon the Congress, Patel would have been the first Prime Minister of India. One of Nehru’s early biographers, Frank Moraes laments at the absence of Patel in the wake of a Caesarized Nehru: “Had Vallabhbhai Patel, who by swift incorporation of the princely states laid the foundation of independent India’s unity, been alive he might have served as a restraining and guiding hand. But in India today there is no one to restrain or guide Nehru. He is a Caesar. And from Caesar one can appeal only to Caesar.”[5]

Right from the start, Nehru began interfering with Ministries not directly under his charge.[6] Judith Brown says in her political biography of Nehru that Lord Mountbatten “told Nehru that even Winston Churchill, in the hay day [sic.] of his power, would not have dared to ride as roughshod over his Ministers as Nehru seemed to be doing.”[7]

Nehru did everything he could to destroy all opposition from outside and within the government. He even changed the constitution of the Congress so that his daughter Indira Gandhi could rise in the ranks without opposition from heavyweights like Morarji Desai and Jagjivan Ram.[8]

Earlier, Gandhi too perhaps sensed that things were not all too well with the Congress. After the All India Congress Committee meeting in December 1947, Gandhi told his followers: “…the best thing for the Congress would be to dissolve it before the rot sets in…”[9]

But this didn’t happen. And Singh goes as far as to say: “…Nehru’s supremacy over the Congress between 1951 [after Patel’s death] and 1964 [Nehru’s death] was even greater than Gandhi’s between 1920 and 1947, because Gandhi did not have the power of government behind him.”[10]

Not only did Nehru actively destroy opposition, he was also brazen about his repugnance towards his political rivals. K. M. Munshi writes that when Sardar Patel died in December 1950, Nehru issued a direction to the ministers and secretaries not to attend the funeral in Bombay.[11] When Rajendra Prasad died in 1963 in a Patna ashram, Nehru not only refused to change the schedule of his Rajasthan fundraising tour but also advised Dr. S. Radhakrishnan against going.[12]

Foreign policy under Nehru was an unmitigated disaster. For example, on the issue of Kashmir, Nehru approached the United Nations without consulting anyone in his Cabinet.[13] Again, it was he who personally decided that it was a good idea to go ahead with the plebiscite in Kashmir even though his Cabinet was totally opposed to the idea.[14] It was Nehru who readily recognized Tibet as an integral part of China.[15] In wake of this, Rajendra Prasad wrote in a letter to Sri Prakasha, “In the matter of Tibet, we acted unchivalrously… I feel that the blood of Tibet is on us.”[16]

Nehru was comfortable signing the Indus Water Treaty with Pakistan by sacrificing India’s interest but he did nothing to resolve the Narmada or the Kaveri disputes within India.[17] An instance of what might actually be called treason was Nehru’s decision to hand over Berubari to [East] Pakistan without even consulting the West Bengal government (which was then led by veteran Congress leader Bidhan Chandra Roy).[18]

Similarly, in 1962, despite growing evidence against the Chinese preparation for attack, Nehru was not prepared to change his opinion about the Chinese peril till the actual day of attack.[19] Many members of the opposition even accused Nehru of issuing orders not to fire on Chinese troops. A committee was appointed, consisting of Lt. Gen. Henderson Brooks and Brig. P. S. Bhagat, to look into the humiliating defeat of India in 1962. Nehru refused to release it for publication and it has not been published to this day.[20]

Nehru’s political life abounds in double standards. Our traditional wisdom advises us to find consistency in manasā, vācā, karmaṇā (thought, word, deed). While it would be pure conjecture to get into Nehru’s thoughts, his words and his deeds have often been poles apart. It would not be wholly unfair to call him the patron saint of double standards.

Nehru himself remained absolutely free from the taint of corruption or greed for money but he didn’t take any effective steps to stem the growing tide of corruption in the ranks of the Congress.[21] A striking example is that of Nehru publicly defending his secretary M O Mathai, who was accused of corruption in February 1959. An informal enquiry revealed that he had been paid by both Indian businessmen and the CIA for information.[22]

While Nehru hated dictators like Stalin and Hitler, he ended up becoming one himself.[23] He hated casteism and spoke vociferously against the caste system[24] but for the sake of winning elections, he was willing to use the caste card. He hated capitalism but if the capitalists were willing to fund his election campaign, he was more than happy to have a quid pro quo arrangement. He wanted to bring land reforms but didn’t push it because his party members were making money otherwise.[25] He paid lip service to socialism even as he agreed to the amendment to the Companies Act so that big industrialists could make open donations to the Congress party. [26]

In his early days as the Prime Minister, he proclaimed that the All India Radio should be built on the lines of the BBC, free from political interference, but soon it ended up becoming Nehru’s mouthpiece and continued to dutifully serve the Congress party till 1977 [end of the Emergency].[27]

Nehru hated communalism but in the 1964 by-election in Amroha, he allowed the Congress to mobilize Muslim Maulanas from Deoband and Ajmer to incite the religious sentiments of the Muslims. This saw a phenomenal rise of 22% of votes from the 1962 election for the Congress candidate.[28]

Even earlier, there were instances of the Congress asking minority communities to vote en-masse for them by influencing the religious leaders in those communities. For example, a Bishop of Kottayam issued an appeal to all Christians of Kerala to vote for the Congress in the 1957 elections.[29] In 1962, Nehru asked his friend Dr. Syed Mahmud to call out to Muslims all over the country to vote for Congress.[30]

Nehru carefully managed the Hindu-Muslim divide in India after independence. As far as he was concerned, secularism was only for the Hindus to practice. For example, while he was eager to pass the Hindu Code Bills, a series of laws that would change the Hindu personal law, he was not willing to even explore the possibility of a Common Civil Code for all communities.[31]

In the seventeen years he was in power, he got the Fundamental Rights amended seventeen times but did not touch the provisions of Directive Principles, which would have reduced the great divide between members of different castes and religions.[32]

Singh’s research and attention to detail are laudable and so is the lucidity of his language. A wonderful feature of his work is the inclusion of rare letters written by and to Nehru especially in the early years of freedom. If the research did not impress, the raw emotions in these letters succeed in painting a pen picture of the troubled son of India, who has evoked such contrary responses from Indians in the last hundred years.

While much has been written about the greatness and vision of Jawaharlal Nehru, this biography looks into the darker recesses of the man and shows him for what he was. Not only does Singh succeed in exposing Nehru but also indirectly ends up explaining to the modern reader many of the glaring loopholes seen in Indian public life today. (Yes, many of them can be directly linked back to Nehru’s blunders.)

At any rate, when studying the complex and riveting personality of Nehru, one can only be confused and muddled as Subash Chandra Bose was, when he wrote to Nehru thus: “You are in the habit of proclaiming that you stand by yourself and represent nobody else. At the same time, you call yourself a socialist—sometimes a full-blooded socialist. How a socialist can be an individualist as you regard yourself beats me. The one is anti-thesis of the other.”[33]

At any rate, when studying the complex and riveting personality of Nehru, one can only be confused and muddled as Subash Chandra Bose was, when he wrote to Nehru thus: “You are in the habit of proclaiming that you stand by yourself and represent nobody else. At the same time, you call yourself a socialist—sometimes a full-blooded socialist. How a socialist can be an individualist as you regard yourself beats me. The one is anti-thesis of the other.”[33]

References-

[1] Historical Essays and Studies, Eds. Figgis, J. N. and Laurence, R. V. London: Macmillan, 1907

[2] Singh, R. N. P. Nehru: A Troubled Legacy. New Delhi: Wisdom Tree, 2015. [hereafter Nehru] p. 7

[3] Tendulkar, D. G. Mahatma. Vol. 2. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, 1979. pp. 488-89

[4] Brecher, Michael. Nehru: A Political Biography. Oxford University Press, 1959. p. 314

[5] Moraes, Frank. Jawaharlal Nehru. The Macmillan Company, 1958. p. 482

Patel being India’s first premiere would have made a world of difference but even today there are unenlightened people who without having studied historical details make frivolous remarks about Patel: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/litfest/litfest-delhi/news/Had-Patel-been-PM-India-would-be-Pak-Ilaiah/articleshow/49976097.cms

[6] Nehru, p. 12

[7] Brown, Judith M. Nehru: A Political Life. Oxford, 2003. p. 180

[8] Ghose, Sankar. Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography. New Delhi: Allied Publishers, 1993. p. 316

[9] Nayyar, Pyarelal. Mahatma Gandhi: His Last Phase. Vol. 2. Navjivan Publishing House, 1958. p. 675

[10] Nehru, p. 23

[11] Ibid., p. 45

[12] Ibid., p. 63

[13] Ibid., p. 28

[14] Ibid., p. 88

[15] Ibid., pp. 53-54

[16] Munshi, K. M. Pilgrimage to Freedom. Vol. 1. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1967. p. 289

[17] Nehru, p. 91

[18] Ibid., p. 91

[19] Ibid., p. 129

[20] Ibid., p. 133

[21] Ibid., p. 69

[22] Ibid., p. 103

[23] Ibid., p. 68

[24] Parliamentary Debates, 16 May 1951

[25] Nehru, p. 77

[26] Ibid., p. 107

[27] Ibid., p. 173

[28] Ibid., pp. 81-82

[29] The Hindustan Times, New Delhi, 20 February 1957

[30] Nehru, p. 82

[31] Ibid., p. 51

[32] Ibid., p. 87

[33] Rao, Amiya and Rao, B. G. Six Thousand Days: Jawaharlal Nehru, Prime Minister. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers, 1974. p. 17