“Just imagine the most difficult and delicate situation in which we were placed at the time of attaining independence, with some 600 Indian States of all shapes and sizes and in different degrees of advancement and development, each free to join either India or Pakistan or to remain independent. Think of the problem which Kashmir had presented and which remains unresolved even after 12 years of independence. Think what would have happened if the problems of Baroda and Jodhpur, Indore and Hyderabad had remained unresolved. And then you will understand the significance of the integration of all the states with India…”

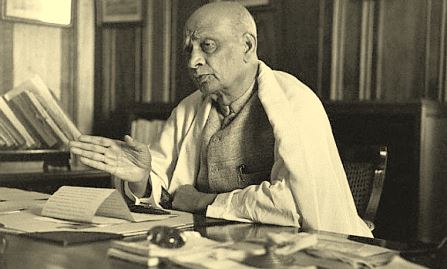

India’s first President Dr. Rajendra Prasad, writing on 13 May 1959 on the contribution of Sardar Patel to the country explained the steep challenge the testing circumstances then posed to the political unity of India in these words. He continued:

That there is today an India to think and talk about is very largely due to Sardar Patel’s statesmanship and firm administration which not only abolished all the States with the consent of the Rulers but also evoked patriotic sentiments in them to such an extent that they were grateful to him for all that he had done..

And then he painfully adds that the country has not adequately remembered the Sardar’s contribution:

No attempt has been made in Delhi to erect a memorial. Even the portrait in the Parliament House is the gift of a ruling Prince (Gwalior). Let us not, therefore, run away with the thought that his services are any the less valuable because we choose not to recognise them.

It must be admitted that Sardar’s life and contribution has not received the appreciation that it deserves. Narrow political interests, particularly by the Congress party—the party that has ruled the country for the longest period since 1947—have held back efforts to give the Sardar his due.

One prime reason for this is that after the Sardar’s death, Jawaharlal Nehru was unopposed both in the Government and in the Congress party. The Congress Party, which till then was a pantheon of great leaders, became Nehru’s personal fiefdom. Over the years, with the perpetuation of the Nehru dynasty as the leaders of the Party, the Congress became nothing more than a personal vehicle for the dynasty to gain political power in successive polls. And once the Party took this shape, all those leaders who had fundamental differences with Nehru were either sidelined or their memories obliterated from public memory or both.

As with most things, this charade couldn’t go on for long. With increased education, access to more information and more importantly, a gain in the strength of non-Nehruvian forces politically, the Congress party’s political erosion began.

Sardar Patel’s was a great life, lived only for the sake of exalted ideals. He was the embodiment of strength of character, a leader who dedicated and sacrificed his all for a great cause, a hard worker par excellence, a politician with a rare gift of practical insight into issues and a statesman who was an exceptional blend of decisive administrative acumen with a rare ability of arousing patriotic sentiments and unstinted loyalty from his followers.

He was a great organizer. He was not called the Mahatma’s ‘muscle man’, without a reason. It was Sardar’s great organizational ability that was the backbone of all of Mahatma’s satyagrahas. Be it the Bardoli Satyagraha of 1928 or the Dandi March of 1930, it was the Sardar who literally ‘baptized’ thousands of people with patriotic zeal and brought them into the stream of the freedom movement.

He was perhaps the only few leaders who truly deserved the epithet of “son of the soil.” No one championed the interests of the farmers in the manner he did. With a keen understanding of the problems of the peasants, he sowed the seeds for large cooperative movements that later changed the face of agriculture and dairy farming in the country.

The Sardar was also an exceptional scholar. His contribution to the making of our Constitution has not received the appreciation it actually deserves. Many important provisions that were contentious could be passed in the constituent assembly only with the stamp of Sardar’s approval. And to those provisions that the Sardar thought were dangerous to the country in the long run, he unfailingly raised his objections.

And it was only because Sardar Patel was as exceptional as he was that Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee chose to call him “the most valiant champion of India’s freedom and the strongest unifying force in our national life.” Mukherjee found in the Sardar “a rare combination of idealism and realism, of strength and generosity which made him a leader and a statesman who had no equal.”

The fact that Dr. Mukherjee— who was a fierce opponent of the Congress— showered such glowing tributes on the Sardar is a testimony of the Sardar’s ability of commanding admiration and respect not only from the members of his own party, but also from its fiercest critics. Most of us are unaware that it was Sardar’s insistence that led to the induction of Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee and Dr. BR Ambedkar—both ferocious opponents of the Congress— as ministers into the first cabinet under Jawaharlal Nehru’s Prime Ministership.

V. Shankar, who was Sardar’s secretary from 1946 to 1950 recounts his exceptional quality of bringing together people of different ideological affiliations to work for a larger national goal:

Though a strong party man, Sardar could, in the wider interests of the country not only bend but also secure the co-operation of other elements in the national life. One outstanding example of it was the manner in which he advised Pandit Nehru to form his Government after Independence which not only had a truly national character but in support of which he had no compunction in securing the services of life-long opponents of the Congress such as Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Shri Shyama Prasad Mookerji. One of the greatest proof of his broadmindedness was the manner in which he could rise above party politics and implement policies which might mean a dilution of party commitment in the larger interests of the country. I cannot think of any contemporary politician of those days or those who have risen to prominence ever since who could make such a deep impression even on those who were opposed to him. (My Reminiscences of Sardar Patel; V. Shankar, vol.2, Delhi: Macmillan&Co., 1975, p.132.)

This accommodative temperament was one of the many differences between Sardar Patel and Nehru’s characters respectively. It did not matter to Sardar if the people he worked with did not belong to his party; it did not matter if they differed on a few issues with him; he stood shoulder-to shoulder with all those who placed the interests of the country above all else. But at the same time, he was wary of the people who chose narrow ideological and communal interests over the country.

He was particularly distrustful of the Communists. He warned time and again of the nefarious anti-national designs of the Communists, both inside and outside the Parliament:

There is a party which had made Hyderabad notorious in the world. They are Communists…they are nothing but murderers and dacoits.

He had issued them a stern warning:

We do not interfere as long as they are working for the uplift of labour or the peasant. But if they incite labour to violence, we have to deal with them firmly. Their object has been to create dislocation and disruption. We cannot allow the breakdown of Government or organised machinery by force or coercion….

Also, it is interesting to note that the Sardar was cagey of the Communist infiltration that was already taking place in the various limbs of the Government, thanks to Nehru’s fondness for them:

And we have to beware of Communist cells inside Government itself, the increasing evidence of which is causing us serious concern. We are proposing to set up a high-level committee of Secretariat officers which will constantly keep the problem under review, obtain decisions of Government on matters of policy and ensure that those decisions are promptly and effectively enforced. You might find a similar body useful in the provincial sphere. (Ibid)

When faced with impractical demands by Muslim fundamentalists, the Sardar’s stance was uncompromising. In the Constituent Assembly, when a few Muslim members demanded separate electorates ostensibly to protect the interests of the minorities, he thundered:

The agitation was that “we are a separate nation, we cannot have either separate electorates or weightage or any other concessions or consideration sufficient for our protection. Therefore, give us a separate State”. We said, “All right, take your separate State”. But in the rest of India, in the 80 per cent of India, do you agree that there shall be one nation? Or do you still want the two nations talk to be brought here also? I am against separate electorates. Can you show me one free country where there are separate electorates? If so, I shall be prepared to accept it. But in this unfortunate country if this separate electorate is going to be persisted in, even after the division of the country, woe betide the country; it is not worth living in. If the process that was adopted, which resulted in the separation of the country, is to be repeated, then I say: Those who want that kind of thing have a place in Pakistan, not here. Here, we are building a nation and we are laying the foundations of One Nation, and those who choose to divide again and sow the seeds of disruption will have no place, no quarter, here, and I must say that plainly enough. (Constituent Assembly Report on Debate, August 27 , 1947, vide: , vol.5.)

Making a speech like this is unthinkable in today’s political circumstances. The person making such a forthright speech would be instantly derided and condemned as communal. Such is the perversion the Leftists and their ilk have brought to our national political discourse. But that is a matter outside the scope of this piece.

Returning to the Sardar, he was equally uncompromising when it came to matters of national sovereignty and integrity. Perhaps nobody else could be as well aware of the value of sovereignty and integrity as the person who stitched together the political fabric of modern India.

When Kashmir was invaded by Pakistan-supported Mujaheedin troops, the Sardar roared:

I should like to make one thing clear, that we shall not surrender an inch of Kashmir territory to anybody. (Life & Work of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Pg 54)

If not for the Sardar’s timely action of immediately dispatching troops to Kashmir to throw the invaders out, Kashmir would have been permanently lost to India. Notwithstanding this great contribution to Kashmir, Nehru divested Kashmir from Sardar’s portfolio of Home and States. This had greatly disturbed Sardar.

H.V. Kamath, the veteran member of the Constituent Assembly, records:

Sardar Patel once told me, with a ring of sadness in his voice, that “if Jawaharlal & Gopalaswami Ayyangar had not made Kashmir their close preserve, separating it from my portfolio of Home & States,” he would have tackled the issue as purposefully as he had already done the Hyderabad problem. It is also a matter of regret that Nehru paid no heed to his warning on China… (H.V.Kamath, “His Variegated Role in the Constituent Assembly” in Maniben Patel & G.M. Nandurkar ed., This was Sardar – the Commemorative Volume, Ahmedabad: Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Smarak Bhavan, 1974, p.335)

Nehru’s personal liking and preferences governed his official decisions and naturally, they had a disastrous impact on the country’s interests. Two examples of this can be given in the context of Kashmir. First, both Gandhi and Sardar were against referring the Kashmir issue to the UN. But Nehru preferred to go with Mountbatten’s advice. Sardar Patel had recorded his displeasure over the decision:

I myself felt that we should never have gone to the UNO and if we had taken timely action when we went to the UNO, we could have settled the whole case much more quickly and satisfactorily from our point of view, whereas at the UNO not only has the dispute been prolonged, but the merits of our case have been completely lost in the interaction of power politics… (Durga Das, Sardar Patel’s Correspondence, 1945-50 , vol.6, Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House, 1973)

Again, Nehru’s personal fondness for Sheik Abdullah made him press for the incorporation of Article 370 – a temporary provision granting special rights to Jammu and Kashmir, which has in effect become permanently temporary— in the Constitution. The Sardar who preferred complete integration and was against any sort of special treatment had to finally relent against his own better judgment owing to pressure from Nehru. Historian Durga Das records it thus:

Nehru favoured incorporation of a section establishing a special relationship with the State of Jammu & Kashmir, thus inferentially recognising the State’s right to frame its own constitution within the Indian Union. Patel wanted the State to be fully integrated with Union. The Cabinet was divided on the issue and the trend of opinion in the Constituent Assembly favoured the Sardar’s stand. But when the matter came before the Assembly, Patel put the unity and solidarity of the Government before everything else and backed the Nehru formula. (Durga Das, , (1969), New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 4 imp., 2009, p.272.)

Even to this day, this dreadful Article has become an impediment to the complete integration of the state of Jammu and Kashmir with the Union of India. It was not only with respect to Jammu and Kashmir that Nehru ignored Sardar’s warning, he threw to the winds Sardar’s caution about Communist China’s imperialist ambitions.

The Sardar’s great insight was not limited to issues of territorial integrity only. He was an efficient administrator par excellence. He knew that his work of integrating the country would not be complete without bringing into being a strong and sturdy frame that would endure and hold the country together at all times. And thus was conceived the Indian Administrative Service.

Sardar Patel was only a home member in Viceroy Wavell’s interim government when a communication from the Secretary of State conveyed the decision of the Secretary to stop further recruitment of ICS personnel indicating the possible termination of the all-India services earlier than the date of the constitutional changes. The sudden termination of the central services had the potential for causing serious trouble and Patel foresaw it. He acted swiftly and acted at two levels. First, he won over the loyalty of the Indian members of the ICS and next, he ordered the formation of a new service—the Indian Administrative Service—as a successor to the ICS.

It was not easy to obtain the consent of the provincial leaders for an all-India service like the IAS, because the provincial leaders apprehended the curtailment of their powers. But as always, Patel knew how to have his way. Convincing the Constituent Assembly on the necessity for having a unified civil service, he said:

The Union [of India] will go, you will not have a united India, if you do not have a good all-India Service which has independence to speak out its mind… an efficient, disciplined, contented Service is a sine qua non of sound administration under a democratic regime. (India’s Bismark- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel; B. Krishna, Pg 72)

When the transfer of power was still four months away, Sardar Patel addressed the first batch of the IAS probationers on 21 April 1947, an address that’s worth reading in detail:

The days of the ICS of the old style are going to be over… The IAS marks the inauguration of an all-India Service officered entirely by Indians and subject completely to Indian control…The days when the Service could be masters are over… Perhaps, you are aware of a saying regarding the Indian Civil Service—that, it is neither Indian nor civil, nor imbued with any spirit of service… Your predecessors had to serve as agents of an alien rule, and even against their better judgment, had sometimes to execute the biddings of their foreign employers…A Civil Servant cannot afford to, and must not, take part in politics. Nor must he involve himself in communal wrangles. To depart from the path of rectitude in either of these respects is to debase public service and to lower its dignity. (Ibid)

And what did Patel offer in return for the services that the ICS and the new IAS officers would render? He promised them

nothing more than the joy which he himself and his colleagues had experienced through such single-minded devotion to what they regarded as the supreme duty, and which he was certain they too would experience. (Ibid)

Sardar Patel knew that the all-India Services would serve as the permanent government, enduring all the political instability if it ever arose. He had said that ‘ministers come and ministers go, but the permanent machinery [the civil service] must be good and firm, and have the respect of the people’.

Unlike many of today’s politicians, the Sardar treated the Civil Servants with great respect and gave them complete independence to do their job. This respect that Sardar bestowed on them was dutifully reciprocated by the Civil Service. K M Munshi tells us how the Civil Servants and even the Rulers of the Princely States mourned Sardar’s death:

Sardar’s treatment of, and dealings with, the Civil Service were throughout informed by a desire to carry them along with him in the service of the nation. The trust he inspired was fully repaid. If there is one sector of the country’s public life which steadfastly remained grateful to him, and still remembers him with love and respect, it is the I.C.S. Their regard for him was exemplified by the unique fact – it had not happened in any other case in the 100 odd years of the history of the I.C.S. – that when Sardar passed away, every member of the I.C.S and the I.A.S in Delhi gathered in a solemn assembly and passed a genuinely felt resolution of condolence. On no other occasion and in the case of no other person have Civil Service paid such an affectionate tribute.

Likewise, oddly enough, nowhere else in history have dethroned Rulers mourned the demise of their silent, peaceful conqueror. (Pilgrimage to Freedom, KM Munshi)

Looking at our experience of six decades as a representative democracy, it can be said that if we have successfully endured the turmoil of our politics, unstable governments both at the centre and at the states, and yet have managed to not only remain a unified country but also achieve considerable economic progress, a large share of the credit must go to the all-India civil services.

It was the Sardar’s vision that not only welded the country into one by integrating the numerous princely states, but by creating the all-India Services, he made sure that the welded structure remained intact for the future.

In a span of just three years after the country attained independence, Patel had achieved all of this. He had made arrangements for the well-being of the great number of refugees who came from Pakistan, wrested back Kashmir from the Pakistani invaders, literally and metaphorically stitched together the political map of the country, performed a scholarly task in helping draft a sublime Constitution for the country, laid the foundation for the reconstruction of the Somnath Temple which he thought was a ‘point of honour for Hindu sentiment’, brought into being the all-India administrative services and finally and most importantly, gave the country—in its very infancy—a solid foundation by his decisive and courageous leadership which was markedly different from Nehru’s pusillanimity.

This courageous leadership of the Sardar was acknowledged and appreciated by even the most adversarial of British leaders. Winston Churchill, sometimes referred to as the angry British bulldog, while bemoaning the disappearance of the title of the Emperor of India from the Royal titles had arrogantly said in 1948 that ‘power will go into the hands of rascals, rogues and free-booters… These are men of straw of whom no trace will be found after a few years’. Churchill had also predicted complete balkanization of India. But the Sardar proved Churchill’s predictions wrong. Also, he could not stomach the insult to India and its leaders. From his sick-bed at Dehra Dun, Patel gave Churchill a blistering reply, calling him ‘an unashamed imperialist at a time when imperialism was on its last legs.’ He went on to call him ‘the proverbial last ditcher for whom obstinacy and stupid consistency count more than reason, imagination or wisdom.’

Patel also gave a stern warning to Britain:

…I should like to tell His Majesty’s government that if they wish India to maintain friendly relations with Great Britain, they must see that India is in no way subjected to malicious and venomous attacks of this kind, and that British statesmen and others learn to speak of this country in terms of friendship and goodwill.

Interestingly, Churchill took Patel’s counter-attack in good stead and through Anthony Eden, his earlier foreign secretary, sent Patel a message saying that he had ‘thoroughly enjoyed the retort’ and that he had

nothing but admiration for the way the new Dominion had settled down to the tasks and responsibilities, particularly those involving relations with the Indian States.’ He also had specifically said that Sardar should “not confine himself within the limits of India, but the world was entitled to see and hear more of him. (India’s Bismark- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel; B. Krishna, Pg 72)

But what did the Sardar recieve from his own country’s Prime Minister in return for this colossal range of services that he had selflessly rendered for his country?

When he lay in his death bed suffering from health conditions that had only worsened to a great extent because of his distraught relationship with Nehru, Nehru divested the Sardar from his ministerial responsibilities. Sardar’s secretary V. Shankar has recorded this painful episode:

Sardar had received a letter from Pandit Nehru expressing concern about his health and hoping that the change [in Mumbai] would do him good. In the letter he also conveyed to Sardar that he would not have to deal with his departmental affairs but that the States Ministry would be looked after by Gopalaswamy Ayyangar and Home Ministry by himself. Knowing full well that the arrangements would hurt Sardar in the current state of his health with a weakening heart and progressive failure of the kidneys, I decided in consultation with Maniben, not take the risk of showing him the letter. I am convinced that thereby I prevented Sardar from harbouring the last feelings of anguish and distress at Pandit Nehru’s attitude with the possibility of an aggravation of his condition. (V. Shankar. Vol.1, Delhi: Macmillan & Co., 1975, p.158.)

In a few days after this letter, Sardar Patel breathed his last. And Nehru asked his government officials not to attend Sardar’s funeral.

With Sardar Patel went all morality and strength of character that was needed to guide the country at a time when these qualities were needed the most. History stands as proof that Jawaharlal Nehru failed India in almost every sphere. Indeed, this was spelled out best by V.P. Menon, who remarked that “if the Sardar had been alive he would have steered us clear of many of the pitfalls we have fallen into since his death.”

But today, on the 63rd death anniversary of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel both history and India remembers him with gratitude for all the sacrifices he has made, and still cherishes his memory fondly as the Only Sardar, as the best Prime Minister India never had.

An alumnus of IndiaFacts, Tejasvi Surya is an Advocate practicing at the High Court of Karnataka, at Bangalore. He is also the co-founder of Centre for Entrepreneurial Excellence, an organization running projects in the spheres of education, employment and entrepreneurship. Tejasvi is currently the State Secretary for Bharatiya Janata Yuva Morcha, Karnataka.