It was by sheer chance that Narendra Singh Sarila came across certain documents which revealed that the partition of India was linked to the great game being played between Britain and the USSR at the time. Without this accidental discovery, the riveting story of India’s partition may have remained buried in the heap of archives somewhere in a London library.

Encouraged by this chance discovery, Sarila expanded his research into the archives of the British Library London, Hartley Library South Hampton, Broadland Archives, United States Foreign Relations documents and Nehru Memorial Museum. The result of this extensive research is a path breaking book- Shadow of The Great Game, The Untold Story of India’s Partition.

Sarila has the right credentials to write this tale. Son of the Maharaja of Sarila, he was the Aide de Camp of Mountbatten in 1948 and served in the Indian Foreign Service from 1948-1985.

Here is the tragic story of India’s partition. It throws a completely new light on the established narrative of the partition and independence of India. The history we have been taught would have us believe that irreconcilable Hindu-Muslim differences forced the reluctant British rulers to partition India and Gandhi’s non-violent resistance got the British to pack their bags. Let us see what the truth really was.

The Great Game

After the Czars had expanded their empire to within 100 miles from Kashmir, the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) had become a very strategic region for the British Empire. Especially after the 1857 mutiny, the British feared that disgruntled Indian rulers would begin intriguing with the Russians. From a Russian perspective Asia was to them what undiscovered Americas was to Europe: savages needing to be civilized and controlled.

After the second World War the Russians became a formidable power in Eurasia. The British feared that if India fell under the Russian influence, it would mean the eclipse of the British Empire. Thus, started a clash between the British and Russians that Rudyard Kipling termed ‘the Great Game.’

In April 1946, the British Chiefs of Staff Field Marshal Viscount Allenbrooke, Air Marshal Arthur William Tedder and Admiral Rhoderick McGrigor reported to the British cabinet:

‘Recent developments made it appear that Russia is our most probable enemy and to meet its threat, areas on which our war effort will be based and without which it would not be possible for us to fight at all, would include India.’

The man who first grasped the strategic importance of India for the survival of the British empire, was Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, viceroy from 1943-46. He recognised that the British power was fading, and it was a matter of time before Britain would have to withdraw. In his estimate the Congress party which would rule India would not cooperate with British interests. This breach, he figured, would have to be plugged by making the Muslim League succeed in separating the Northwest from the rest of India.

Wavell noted in his diary that Churchill too had visualised the division of India. In fact, Churchill’s idea was a division into three parts, Pakistan, Hindustan and Princesstan. Wavell, however, had envisaged then a division of India as it actually happened later. This plan was known secretly within the British leadership as the Wavell plan of Pakistan.

By early 1947, the British military and leadership were in overwhelming agreement to retain strategic control over Northwest India. Thereafter they played an intricate game to finesse a blundering Congress Party, use Jinnah to achieve their strategic goal and to fool the Americans who had other ideas.

How the Congress was Finessed

The British strategic objective was to retain control over the Northwest by partitioning India.

The Muslim objective was a little complex. In the provinces where Muslims were in majority (about 70-75% of Muslim population), there was no feeling that Islam was in danger. The Islam in danger narrative had appeal in Muslim minority provinces only. Majority of Muslims were confident of avoiding Hindu domination. They saw Hindus as both divided and passive, who could be easily bullied. Even fundamentalists like Abdul Al Mawdudi of Jammat-i-Islami did not want partition as they did not approve of Jinnah’s non-Islamic ways. However, there was a small elite led by the likes of Agha Khan, Liaqat Ali Khan and Syed Ahmad Khan who wanted a separate Islamic state. Jinnah himself, was initially against a break up, but scorned by Gandhi and Nehru he later wanted Pakistan in any shape or size.

The objective of the Congress Party, effectively the sole political force representing Hindu interest, should have been to defend the territorial integrity of India at any cost.

The Americans were of the view that an undivided independent India was crucial to gain their much needed cooperation in the war effort. Second an independent united India would give a positive signal to the rest of Asia. ‘Asia for Asiatics’ was a significant part of the American vision for a post war world order.

Jinnah Floats the Two Nation Theory

Gandhi squandered a hard won election victory in 1937, by resigning from the provincial governments as part of his badly timed Quit India movement. This move had exactly the opposite effect than what was intended. The British were determined to not let anything come in the way of the war effort. Instead of feeling pressured they simply reduced their dependence on the Congress and thus its bargaining power. Further the vacuum created, gave a god sent opportunity to Jinnah. A delighted Jinnah termed the Congress move a ‘Himalayan blunder.’ The distinguished civil servant V P Menon noted that ‘by resigning the Congress Party showed a lamentable political wisdom.’

On 24th March 1941 Jinnah proclaimed that Muslims were a separate nation. This suited the British plan. By strengthening Jinnah, the British were making Gandhi increasingly irrelevant. His loud proclamations of non-violence were not sitting well with the British in the midst of a tough war. In 1940 Gandhi told Viceroy Linlithgow:

‘Let them (the Germans) take possession of your beautiful island, if Hitler chooses to occupy your homes vacate them, if he does not give you free passage out, allow yourself, every man, woman and child to be slaughtered.’

Jinnah’s scheme for Pakistan included NWFP, Baluchistan, all of Punjab, Delhi, Sind, all of Bengal, Assam, Hyderabad and all other Muslim princely states and a corridor connecting East and West Pakistan

The Congress party, being neither farsighted nor adamant on a united India, did not counter Jinnah’s preposterous scheme. Nehru reasoned that taking the idea seriously would encourage separatist forces. It wasn’t until 1944 that Gandhi said that Hindus and Muslims were not separate. He argued that Muslims were descendants from converts and there was no precedence in history of a change of religion changing nationality. The result was that the two-nation idea was not nipped in the bud and Jinnah was politically strengthened.

The irony of Jinnah was that for the first sixty years of his life he fought for a united India. Jinnah’s difficulties began after Gandhi returned from South Africa in 1915. In the 1920 Nagpur Congress session Jinnah and Gandhi clashed. Jinnah was openly booed in the presence of his young wife Ruttie, with Gandhi refusing to intervene. In 1928 Jinnah persuaded the Muslim league to give up separate electorate in return for 33% Muslim seats in the central legislature, separation of Sind from Bombay Presidency and recognition of NWFP and Baluchistan as separate entities. This, he reasoned, would enable the Muslims to dominate five provinces and help reduce communal differences. The Congress rejected this proposal. Angling for his son Jawaharlal to be elected Congress President, Motilalal Nehru did not want to risk upsetting Congress leaders by supporting Jinnah. In the midst of this major crisis in his career, Ruttie decided to leave him. Badly scarred, Jinnah left for England in 1933 to concentrate on his legal practice.

It was Liaqat Ali Khan who persuaded Jinnah to return and contest the 1937 elections. Jinnah was unsure of countering Gandhi’s ability to mobilise the masses. Khan assured him that he will arrange the means to win them over. He did not, however, reveal that whipping up fanaticism was the weapon he had in mind. Jinnah returned and set upon the task of rebuilding the Muslim League. He was now consumed by a burning desire to vanquish the Congress and get even with the arrogant Nehru. For the first time he began to see Mohammad Iqbal’s idea of a separate Muslim state as a way to achieve personal glory.

In the end Jinnah emerged a tragic Shakespearian character. Exploited by hard liners like Liaqat Ali Khan, used by the British and consumed by his own ambition, he died a bitter man. Colonel Ilahi Bakhsh, his doctor heard Jinnah say, ‘I have made Pakistan, but I am convinced that I have committed the greatest blunder of my life.’

The Cripps Mission

In 1941 the Allied forces were suffering reverses. The attack on Pearl Harbour had drawn America into the war. Roosevelt was putting pressure on Churchill to grant self-governance to an undivided India. He felt that this was best course to gain India’s cooperation in the war effort. Viceroy Linlithgow, however, was of the firm opinion that no concession should be granted to the Indians at this crucial juncture in the war. He was certain that any agitation caused by Gandhi could be brought down.

To deflect the American pressure, Churchill decided to send Sir Stafford Cripps to India. The mission was a smoke screen designed for deliberate failure. The covert plan was to placate Roosevelt and put the Congress in a dilemma. The Cripps Plan was:

- Immediately after the war India would be independent either within or outside the Commonwealth.

- In the interim a politically representative Executive Council would be formed under the Viceroy.

- The princely states would have the right to stay out of the proposed Indian Union if they so choose.

- The proposal had to be accepted or rejected as a whole.

For the first time the idea of princely states not being part of the union was mooted. The real motive behind the mission can be gauged from what Foreign Secretary Amery said to Linlithgow:

‘As for the Congress their adverse reaction may be all the greater when they discover that the nest contains Pakistan Cookoo’s egg.’

On 25 March 1942 Cripps noted:

‘I think Jinnah was rather surprised in the distance that it went to meet the Pakistan case.’

As expected the Congress Party rejected the proposal on 11 April 1942. But surprisingly the resolution rejecting the proposal had this sentence:

‘The Congress working committee cannot think in terms of compelling the people of any territorial unit to remain in the Indian Union against their declared and established will.’

This was inexplicable since the Congress had consistently considered India indivisible. It raised doubts about its commitment to India’s unity.

The British achieved their objectives of placating the Americans, giving Jinnah hope and putting the Congress into a dilemma. The Congress on its part, erred badly in diluting its position on the integrity of India and by not joining the Executive council. It is arguable that by joining they could have exerted power and signaled their cooperation in the war effort. This would have been useful to garner support of the British public and the Americans. The risk of the princely states seceding was low and the majority of Muslims did not want partition.

After the Cripps’s Mission

After the Cripps mission Gandhi became belligerent. This can be discerned by the draft of the Allahabad Congress resolution, leaked to British intelligence by the Communist party. The Communists had switched loyalty from the Nationalists to the British after Russia was attacked by the Germans. This is a sad commentary on the Communist Party too, but that is another story.

The draft asked for the British to clear out and to use force if necessary. Nehru opposed the draft saying that the British would not allow this and would render India into an active war zone. The draft was first accepted and then rejected the same day after Nehru’s threat.

In the draft we have Nehru saying:

‘It is Gandhiji’s feeling that Japan and Germany will win. This feeling unconsciously governs his thinking.’

British intelligence quoted this statement to Roosevelt to denounce Gandhi as ‘a fifth columnist.’

In 1945 Wavell held another conference to discuss the formation of a politically representative Executive Council. Jinnah was tutored by a member of the Viceroy’s council to sabotage the meeting in return for the promise of Pakistan. Hence as early as June 1945 Jinnah was taken into confidence on the creation of Pakistan. This event made Jinnah into a strong leader of the Muslims.

Clement Atlee Becomes Prime Minister

In 1945 Churchill lost the election and Clement Atlee took over as Prime Minister. Unlike Churchill, Atlee liked to operate from behind the scene. His objective was to partition India but make it appear that the Congress wanted it. His second objective was to persuade Jinnah to accept a truncated Pakistan. As we have seen there existed a Wavell plan of Pakistan which was pretty much how Pakistan was finally created.

He instructed Cripps to reach out to Nehru and ask for his suggestion. On 27 January 1946, Nehru wrote a 3500-word letter.

The gist of the letter was:

- The British should grant independence to India and allow it to frame its own constitution.

- The British should not divide India. Only after a plebiscite can territories that wished to secede could do so.

- Pakistan was a non-starter because the vote for Muslim League did not mean a vote for separation.

- Although there was a feeling that the British would not leave without force, he was in favour of a negotiated settlement.

Again, Nehru failed to stand firm on India’s territorial integrity be mentioning plebiscite. Not surprisingly, Atlee decoded this as the Congress being ‘flexible’ on separation. The assurance of eschewing force and negotiating a settlement was an added relief. Atlee now instructed Cripps to work towards Wavell’s Pakistan. The Cabinet Mission was the next major event.

The Cabinet Mission 1946

In March 1946 the Cabinet Mission arrived in India to devise a mechanism for smooth transfer of power. It comprised Sir Pethick-Lawrence, Secretary of State for India, Sir Stafford Cripps, President, Board of Trade and A V Alexander, First Lord of the Admiralty.

The key features of the Cabinet Mission plan were:

- Acceptance of the Muslim fear of Hindu domination.

- Grouping of provinces into A, B, C. Sizable Muslim populated areas into B and C (North West & East of India), to be controlled by the Muslim League. However, a separate state of Pakistan was ruled out.

- After ten years Groups B & C could secede if they so wished.

- The Union of India will have three subjects under its control-Foreign Affairs, Defence and Communication. The provincial governments will control other subjects.

- No clause could be modified without majority of representatives of the two political formations and majority of representatives of the constituent assemblies agreeing.

Atlee’s plan was to somehow induct Nehru and Patel into the government to prevent the Congress from revolting. Second to browbeat Jinnah into accepting a truncated Pakistan.

Jinnah was suspicious about a plan that rejected the idea of an independent Pakistan straight away. The Labour politician and journalist Woodrow Wyatt was tasked with convincing Jinnah that this plan was the first step on the road to Pakistan. He writes:

‘When I finished his (Jinnah’s) face lit up. He hit the table with his hand. That’s it, I said, you’ve got it.’

Jinnah accepted the plan.

As had been the pattern, the Congress’s response was inconsistent and confused. Gandhi did realise that the proposal was a trap. No provision for an independent Pakistan was to bait the Congress, while the acceptance of a principle of Pakistan was to bait the Muslim League. So, while the Congress was willing to accept the idea of an Interim Government, the possibility of B and C breaking away was objectionable.

The Nationalists urged the Congress to renew the Quit India movement, this time violently. The 1946 INA revolt had unnerved the British. They came to believe that the loyalty of the Indian army could no longer be relied upon. Field Marshal Claude Auchinleck had noted ‘wholesale defection and disintegration of the Indian army was possible.’ A full-blown revolt would have perhaps stopped Jinnah’s belligerent Direct action as well.

The Congress leadership felt that a revolt was too risky. They figured that by accepting being in the Interim Government they might somehow be able to ward off partition. They banked on the NWFP, under Congress friendly rule, choosing to stay within India, thus making Pakistan non-contiguous enclaves within Indian borders and therefore temporary.

On 6 July 1946, Nehru announced that the Congress was committed to nothing more than simply entering the Interim government. This prompted Jinnah to reject the Cabinet Mission plan in toto. Jinnah announced Direct action which led to the horrific Calcutta killings. The Congress had failed to see that their restraint would embolden the Muslim League to adopt violent ways.

On 2 September 1946 Atlee succeeded in getting Nehru to join the Interim government. Jinnah saw this as an ominous move. But the British were pleased as the plan was moving in the right direction. N P A Smith, Director of Intelligence Bureau looked ahead:

‘As I have said for some months, Pakistan is likely to come from Congresstan.’ (the acceptance of office by the Congress)

Now Wavell began to work on Gandhi and Nehru to accept the Cabinet Mission’s grouping formula. He argued that without this acceptance the Muslim League would not join the government and more violence will result. Both Gandhi and Nehru rejected the proposal. The Nationalists felt that the only way to keep India united was to be in the government and exclude Jinnah from it. This would help to break away the Muslim leaders opposed to Jinnah.

Wavell however was relentless. He met Nehru on 11,16, 26 and 27 September 1946 to persuade him to take Jinnah on board but Nehru stood firm. Inexplicably on October 2, 1946, Nehru caved in. He told Sudhir Ghosh, a Gandhi confidant ‘Well this man (Wavell) had been pestering me to start talks with Jinnah. A few days ago, I told him in sheer exasperation that if he was so keen to talk to Jinnah he could do so.’

What transpired next was the biggest blow to the united India project. Wavell invited the Muslim League to join the Viceroy’s executive council without either insisting that they join the Constituent assembly or even call off direct action campaign. This was a great victory for Jinnah. He could now sabotage Nehru from within. The move did not stop violence either as the Noakhali riots followed soon after.

The last piece of the action required the secession of NWFP.

How NWFP was Plucked Out

The Congress figured that with NWFP in their hands, the division of Pakistan would at best be enclaves within the borders of India, which could not last for long. This could have worked if they were firm against any division. However, the Congress resolution to bifurcate Punjab and Bengal into Muslim and Hindu parts went against the united India principle. By accepting the division of Punjab and Bengal, the Congress was in principle accepting Jinnah’s two nation theory.

The extent of this blunder can be judged by what the US charge d’affairs in India George Merrell wrote to his government on 22 April 1947:

‘The Congress effort to make Pakistan unattractive by demanding the partition of Punjab and Bengal-Congress leaders have in effect abandoned the tenets which they supported for so many years in their campaign for united India. They have also agreed by implication to Jinnah’s allegation that Hindus and Muslims cannot live together.’

Very significantly this weakened the American position on an undivided India.

On taking over as viceroy in March 1947, Lord Mountbatten asked Nehru what he would do in his (Mountbatten’s) place. Nehru again weakened the position of a united India when he said, ‘it would not be right to impose any form of constitutional conditions on any community which was in a majority in a specific area.’ Mountbatten obviously took this to mean that Nehru was agreeable to the provinces, including NWFP, being given a free choice. He floated the idea of a referendum to which Nehru agreed, sure as he was of a Congress victory. He had erred again by failing to factor in the effect of Gandhian pacifism on the Frontier Gandhi, Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan. Fearing bloodletting, Gaffar Khan decided that his party will not vote in the referendum. The referendum voted for Pakistan by 50.49%. If Gaffar Khan’s party had not boycotted the referendum, albeit with bloodletting, NWFP would have been with India.

The assessment of N P A Smith that Pakistan would come from Congresstan came true.

How the Americans Were Played

The Americans were disposed towards a free undivided India for three reasons:

- Roosevelt figured that fulfilling the Indian aspiration for freedom would encourage them to support the war effort wholeheartedly.

- The freedom and unity of India was required to send a positive signal to the rest of Asia on the post war American plan of ‘Asia for Asiatics.’

- Partition would give a fillip to the dreaded Communist forces.

Churchill played on the American’s lack of knowledge of the complexity of India. In fact, he willfully misled Roosevelt by saying that 75% of recruits were Muslim (only 33% were). He used this to justify acceding to the Muslim aspiration of a separate country.

The Americans were increasingly getting anxious of Gandhi’s belligerence and call for civil disobedience in 1942. Nehru who understood foreign relations better than anybody else at the time got Gandhi to write to Roosevelt appealing to his ideal of freedom and democracy. Nehru also got Gandhi to mention that a free India would be open to allied bases.

Roosevelt did write to Churchill, but the British response was on expected lines. Foreign Secretary Amery pointed out the irreconcilable religious differences in India. He emphatically reassured the Americans that any agitation will be quelled swiftly thus not impacting the war effort. Churchill chipped in with a scathing criticism of the Congress saying that their offer of supporting the war effort in lieu of the British quitting was an eyewash and that they would have no hesitation in joining hands with the Japanese. Realising that this would be a tightrope walk, Roosevelt stopped pushing the issue.

Whatever hope there was of an American intervention was dashed when Congress agreed to the Cabinet Mission plan and division of Punjab and Bengal.

Looking at the Events in Hindsight

Britain’s Pakistan strategy was a spectacular success. Pakistan joined the Baghdad Pact and later the CENTO led by the USA. This formed a defence barrier against Soviet ambition in the Middle East. In 1958, Pakistan provided air bases to the CIA in Peshawar from where they flew U2 spy planes. In 1970 Pakistan helped the US establish a relationship with China to pressurise the Soviets from the East. In 1980 Pakistan played a major role in helping the USA defeat the Soviet Union to end the cold war.

Jinnah got his Pakistan but died a bitter man. The West used Pakistan and when no longer needed, fed it to the wolves. The question needs to be asked if its people benefited from the partition. In 1945 Field Marshal Alanbrooke was prescient when he told the British cabinet:

‘With no industrial development Pakistan would not be able to defend itself. Pakistan will end up identifying with Muslim lands and end up in wars not in its interest.’

The entire saga of colonial rule shows up the British empire as downright unconscionable. The damage they have inflicted on India is so mind boggling that even today we shy away from honestly analysing it. They wreaked cultural destruction, divided the people, impoverished a prosperous country to build their own wealth, inflicted famines that killed so many millions that history must judge Churchill a bigger villain than Hitler. They have their hands soaked in the blood of over half a million people by engineering an avoidable partition. The history of the British Raj from an Indian gaze needs to be written. Even a clinical assessment will be severely damning.

However, the saddest part of this story, is the sheer ineptitude of the Indian leadership. The narrative we have been fed about them is false. The Indian leaders were arrogant, inconsistent, disinterested in foreign affairs, did not understand defence and erred politically time and again. In a predatory world they were easily exploited. Gandhi and Nehru need to be judged unapologetically for what they achieved or did not achieve. They failed to maintain the integrity of the Indian land when partition was imminently avoidable since neither the Muslims nor the Hindus wanted it.

Here is a list of mistakes:

- Rejecting a capable and then secular Jinnah from the Congress party in 1920s made an enemy out of him. If he had been retained in the Congress fold, the story of India would have been quite different. Gandhi should have intervened between Nehru and Jinnah keeping long term national interest above personal likes and dislikes. Nehru should have negotiated harder with Jinnah to keep India united.

- Giving up the gains of a massive electoral victory in 1937 over an ill-timed Quit India movement, made the British distrustful and opened the door for Jinnah. The Quit India movement was timed in the midst of a tough war. The British were in no mood to give any concessions. As it happened the movement was quelled ruthlessly, thousands were killed and over sixty thousand imprisoned. Even aerial machine gun firing was resorted to. After Subhash Bose had dealt a big blow with the INA trials, the time was right for a second Quit India movement, but Gandhi demurred.

- Complete inconsistency in their resolve to keep India united. Not strongly opposing Jinnah’s preposterous two nation theory in 1941; indicating time and again that people could choose to stay in united India or not; agreeing to the trap of the Cabinet Mission plan; losing NWFP, not exploiting Roosevelt’s support for a united India; and not meeting fire with fire on Jinnah’s violent ways.

- Gandhi’s bigger goal appears to have been the ideal of non-violence and not the unity of India. He has to take the rap for this. Nobody can deny Gandhi the credit of galvanizing a broken people into a spiritually inspired force. He caught the imagination of the world and whipped up global sympathy for his cause, but his failure to use this mammoth advantage to achieve his goals has to be questioned. He failed to frame and pursue non-negotiable goals. Despite proclamations of the ideal like non-violence, the masses still ended up losing their lives for nothing.

- Finally, to Nehru, an intelligent man who too could not frame clear goals and work unwaveringly for them, like Jinnah did. If he was clear he would have cooperated with the British and Americans to contain the Soviets, in return for a united India. But his distrust for American capitalism came in the way. He was more interested in following a lofty foreign policy of fighting colonialism and apartheid, than dousing existential fires at home. This greatly embarrassed Britain. He was excited by the prospect of mediating peace between the East and the West. By appealing to the deep felt urges of mankind for freedom, equality and peace, he believed that he could leave his imprimatur on the world stage. He should have learnt that behind lofty declarations countries followed predatory self-interest. These ideas would not persuade the British to abandon the Pakistan scheme.

All in all, this is a tragic tale of a great civilisation squeezed out of its essence. It is not surprising that even the journey to reclaim what is its due, is so uphill. A tale of a people who have a fantastic blue print within their own culture but are unable to access it because of a million broken narratives.

A doha from Kabir is very apt to describe this conundrum:

Pani beech meen piyasi

mohe sun sun aave haansi

A thirsty fish looks for water everywhere, all the time surrounded by it. Isn’t it laughable?

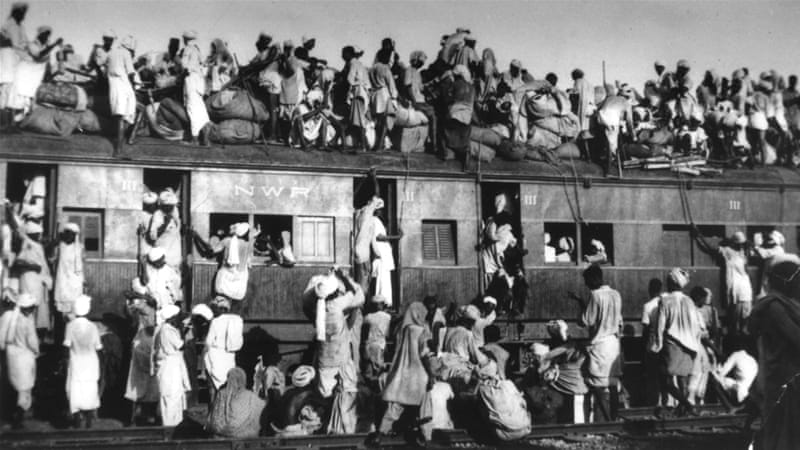

Featured Image: Prabhat Khabar

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness,suitability,or validity of any information in this article.

Atul Sinha founded and runs a leading Strategic Brand Design Company. His interest in Indic culture and history led him to pursue a PhD program at SVYASA, Bangalore. He writes on Vedanta and Indic Culture.