The Union Public Service Commission has constituted a committee “to overhaul the entire examination scheme and suit the selection process to the skills required for each set of services”.

More than six decades after Independence, after the confusion of many earlier “expert” committees, we’re coming around in a roundabout way to officially acknowledging the systemic failure of the Union Public Service Commission to select public servants, as distinct from government servants. [1]

There can be no doubt of the popular perception that the single greatest obstacle to the Prime Minister’s vision for a new India is the administration, headed by the IAS, and that officers are unwilling and unhappy to serve at the Centre because–O tempora!–the man is actually requiring them to work for the people over whom they rule!

Four earlier essays presented the UPSC’s Civil Services Examination as a political system designed to perpetuate a macaulayan and colonial-style administration. [2]

Can this be changed?

This fifth essay, building on the earlier four (and citations there are not repeated here), presents some suggestions for the consideration of the Baswan Committee.

It takes as its motivation the Prime Minister’s call to young Indians that kuchh banne ke sapne mat dekho kuchh karne ke dekho apne aap kuchh na kuchh ban jaoge.

Unfortunately, the contested validity of psychometrics apart, this mantra cannot be tested through public competitive exams of enormous numbers of candidates.

All that can be done through public competitive examinations is to try and long-list candidates with a certain broad minimum aptitude and ability, and then prune them into a shorter list from which a final selection is made.

And so this essay states at the outset that kucch karne ke sapne are not testable through a mass, competitive, written examination.

Dreams of action, of karna, need a muse who inspires them. This is the quality of a leader. All the UPSC can do is select as honestly as it can those it hopes will be responsive to the call of the muse. Yatha raja…..

We start with those with a strong sense of Indian-ness, their feet firmly rooted in India. They must think Indian, though their ideas and thoughts are expected to soar high. But their foundation must be firmly Indian. And so a competitive exam must test their familiarity with and understanding of people, things, and matters Indian and of concern to India – local, national, global.

B S Baswan

The mandate of the Baswan Committee appears tacitly to recognize issues amplified in the earlier essays, though it continues to use conventional jargon geared towards greater efficiency as government servants rather than greater effectiveness as public servants –

- the patent absurdity of a common selection system for 24 different services with 24 different job descriptions and, therefore, 24 different job requirements;

- the macaulayan pre-requisite of English; and

- the biases and prejudices of the examiners.

It follows that –

- there should be different selections for different services;

- English is not essential for effective public service (and the Prime Minister himself is undeniable proof of this); and

- opportunities for subjective biases in evaluation should be minimized.

So, we start by designing a selection system that encourages those young people to apply who it is hoped are seriously interested in public service careers rather than in government jobs, and are prepared to make the strenuous effort to be selected.

All the 24 services are public-service opportunities but their scope and expression vary, and young people must be clear about which ones they believe suit their capability and match their competence. Skills can be acquired, what is needed is motivation and commitment as Indians.

All applicants must show they know, first, about our country and its place in the world and, secondly, about the world. This is and should continue to be the focus of the General Studies (GS) papers, barring the so-called “ethics” paper discussed in earlier essays and about the merit of which there has been some concern even within the UPSC. This paper should be dropped, and the scope of the other papers expanded.

It is pertinent to note here that the objective of reform should not be to tame or eliminate coaching centres, as was for the 2013 changes, but to attempt to select a certain kind of young Indian. The UPSC’s measure to prevent “gaming the system” is a signal failure, with freshly-recruited IAS and other officers, whose “ethics” have been approved by the UPSC, openly tying up with coaching centres to advise aspiring successors on how to game the system.[3]

The level of the GS papers should be NCERT for the concepts, and intelligent and extensive reading of newspapers and journals for real-life examples and applications of these concepts.

The CSE notification uses the phrase “the curiosity of well-educated youth” and this as “the curiosity of well-read Indians” is exactly the guideline for this part of the selection process.

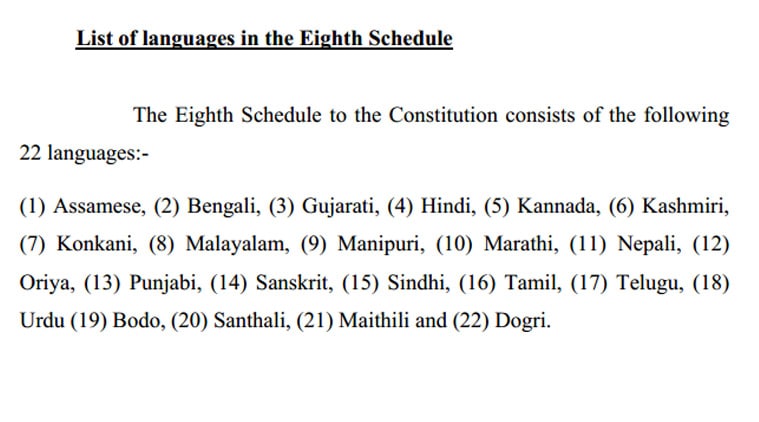

At present, the preliminary examination is in English and Hindi only, and the main examination can be attempted in English or in any of the Eighth Schedule languages (though its questions are only in English and Hindi).

8th schedule of the Indian Constitution

There is no logical reason why the preliminary examination cannot be in English as well as in the Eighth Schedule languages. [4]

Therefore, we have a preliminary – renamed qualifying – examination of two papers, and a new preliminary examination of the GS papers.

Both these examinations should be overwhelmingly data-based and objective, so that language biases in evaluation are reduced if not eliminated.

Then there should be a main services-based examination of two optional papers (Optionals) that test narration, description, analysis, communication and comprehension.

The entire examination should be in English and the Eighth Schedule languages, barring Paper 2 of the qualifying examination which is only about the Eighth Schedule languages. If the Official Language Resolution 1968 comes in the way, it is time it be amended.

Applicants can be graduates in any UGC-recognised subject. This will take care of the Baswan Committee mandate of “fair mix of candidates from different disciplines”. Or do they want quotas of UGC subjects too, so that we must have a certain number of graduates in music, and in forensic science, and in electrical engineering, and in dentistry, and so on? And then such quotas apportioned to each service so that each too has a “fair mix of candidates from different disciplines”?

No change is really necessary in the current Paper 1 of the preliminary examination except that, being of the objective type, there is no reason why it cannot be taken in any Eighth Schedule language.

Translators should be drawn from the Central Translation Bureau or from the Central Institute of Indian Languages. [5]

All candidates must qualify in any Eighth Schedule language. This becomes Paper 2 of the qualifying examination. As argued in an earlier essay, a qualification in English is certainly not a pre-requisite for public service by Indians in our own country, and (grammatically correct) English can always be taught during the training, just as other languages are already being taught.

Paper 1 of the qualifying examination should test for functional literacy about “India”. [6]

The GS papers (now the “preliminary examination”) should take this much farther and wider. An essay paper, presently in English or Hindi, is quite unnecessary, since writing skills will be tested in the services-specific Optionals.[7]

It should be clear that the qualifying and GS papers can be designed to favour the selection of well-read young Indians across the board for many public services, and this should be the minimum expectation for government employment, if not for public service.

The specialization starts with the Optionals which, through the rigour and range of their questions, test the earnestness and dedication of the candidate through specified subjects for a preferred mode of public service. The subject knowledge to be expected should not be of the academic kind, but of how that academic knowledge has been, is or can be applied to real-life needs and situations. In other words, the Optionals are not selecting young people for their potential as academicians, but for their potential as practitioners.

In other words again, how hard can and does a young person study the appropriate subjects, and how well can they do in them, to show their seriousness and motivation for a particular form of public service?

And to show that their endeavour has been assessed fairly, there is no technological reason why photocopies or scans of their corrected answer sheets cannot be given to those who ask for them, after the result is announced, as is done to lesser or greater extent in some public examinations (State Boards, CBSE, RBI).

The final stage is the interview (officially called “personality test”, which is what it should be but actually isn’t) that should be necessary only for those categories of services that involve regular public dealing (that includes the ability to listen and to act) and that require team leadership qualities.

With a qualifying, a preliminary, and separate service-oriented main examinations, there certainly will be a substantial reduction in the number of interviewees for each set of services, though the overall number for all sets may still total lakhs.

This is especially so for the set of development services (discussed later) and the set of police services. So assuming, say, 200 vacancies for the development services, the number to be interviewed will come down to 400, instead of the 3000 or so for the common examination for 24 services.

To reduce the interviewer bias for which the UPSC is notorious, this makes it feasible that each candidate be interviewed twice, by two different boards, one in the morning and one in the afternoon of the same day, and the marks should be the average of the two interviews.

I have earlier described the CSE interviews as a cruel joke and given numerous examples of the biases of the very different chairpersons. There is no perception at all, certainly not amongst candidates, of a level playing-field. Yes, an interview is necessary – but is it necessary for all services?[8] Do the accounts services, which are office-based services and involve very little if any public interaction, really need interviews?

Interviewing should be relaxed, extended over an hour, focused on drawing out the qualities and potential of the young person for the preferred set of services. It should be for understanding the personality of the interviewee, not for dismissing them as is often the experience now. [9]

Weightage should be given (as in B-school admissions) to those who have actually engaged in community or field or other kind of public service, the interviewers satisfying themselves that the experience claimed is authentic.

It is essential that interviewees in languages other than English not be made to appear before chairs with a bias for English. Panelists and UPSC members who do not know Hindi should either not take on Hindi-medium interviews at all (rather than, as happens now, downgrade the candidate for not knowing English), or ensure a Hindi-English professional translator is already present, which never happens.[10]

What therefore is being proposed is a common entrance examination for as wide a range as possible of public services to which recruitment is made annually. Those who qualify (12 to 13 times the total number of vacancies) appear in a common general studies examination. These two examinations are elimination processes.

Those who qualify these are the pool eligible for the specialized examination, and they are separated into smaller pools according to the set of services for which they have expressed their preference. From each smaller pool, the top six to seven times the number of service-set vacancies appear in the relevant optional subjects’ examinations spaced appropriately through the year.

For services or sets of services for which interviews are superfluous, their vacancies are then filled totaling the marks of the GS and the Optionals. For services for which interviews are necessary, a number about twice the number of vacancies are called for the interviews.[11]

This should take care of the Baswan Committee mandate of “an examination pattern that is holistic and does not exhibit any bias for or against candidates from any particular stream, subject area, language, or region.”

Left is the vexed, interconnected issue of quotas, age limits, and number of chances.

It is important to note that “the terms of reference of the committee include suggesting suitable eligibility criteria for candidates, including minimum and maximum age limits and number of attempts, besides reviewing eligibility of candidates already selected to different services but who wish to reappear for selection to some other service.”

Now, CSE quotas are a matter of politics and cannot be divorced from their larger politics in government policy. Suffice it to draw attention to a Supreme Court observation that “the very concept of reservation implies mediocrity”.[12]

It follows from this that any official assistance of any kind (books, stipends, free-ships, coaching, whatever) to those still perceived to be socially or physically or financially disadvantaged should be given to enable them to stand equally at the starting line (the qualifying examination). At the starting line all must start equally and, thereafter, the process and future should be impartial and purely merit-based.

The examination application form should omit the asking of “community” or any other euphemism for a quota category. If this information is needed for census purposes, it can always be asked for later.

PM meeting successful candidates of UPSC examination who were trained at SPIPA, Ahmedabad.

The mandate of the Baswan Committee empowers it to reject the colonial legacy of divide et impera. The UPSC is one of the instruments that has been used by our rulers to perpetuate this legacy. Dare the Committee propose that, 67 years into Independence, we think of ourselves now as Indians rather than as constituents of a divide-and-rule vote-bank politics?

All candidates should appear and progress as Indians. As for the age limit, this presently ranges from 21 to 42, if not higher.[13]

In other words, in the same batch of the same service there can be candidates selected ranging over 21 years in age difference. It is a reasonable expectation that, other things being equal, their energy and productivity levels will vary considerably. The older ones may have family responsibilities too to consider during their first and field postings, and it is an undeniable fact that they will retire very much sooner than their younger colleagues, from positions relatively less senior. In other words, the younger ones can look to a career in public service; the older ones have secured a government job and may very well be beginning to plan for their retirement. It is inevitable that political pressure will build up for the accelerated promotion of the latter category of candidate.

Therefore, the age range should be a youthfully energetic 21 to 26 years.

Given the present age limit, the CSE is surely unique in permitting up to 21 attempts for the same job. This isn’t about public service at all but is about entitlements for government jobs, with the UPSC as a sort of employment agency.

If the UPSC is serious about merit-based public service, then a candidate should be allowed –

- only two attempts in all for any set of services,

- to appear for only two sets of services in a given year, and

- having been selected to any set, must not be allowed to appear again for that or any other set, unless the candidate does not join or, having joined, resigns. In other words, a candidate should not retain a lien in any service while trying for another service, thus blocking a vacancy and depriving another eligible candidate of the opportunity for service.

Of course, within a set, candidates can rank their preference of services, or exclude any.

In sum, two attempts over 5 years to any one set of services and an attempt each year to two sets of services (10 attempts over 5 years) is a generous provision.

Finally, here, the Committee’s mandate of “utilizing information and communication technologies’ should consider means to prevent cheating – there was, for example, rampant cheating in the CSE 2015 prelims in some centres in Jammu. And in many centres for the same examination, the question paper was distributed from an already-open envelope, instead of from a sealed envelope opened in front of all the candidates, as was done in other centres.

So far we have dealt with the objective and an examination towards meeting it, at least to some extent.

By definition, all government services are public services or, at any rate, offer opportunity for public service. But rather than club 24 disparate services together and a candidate aims for one if not another – in other words, the aim is just to become a sarkari naukar – it will be appropriate to club these services into sets which offer – broadly – the same scope and expression of public service.

The criterion for clubbing of services should be approximation of function and not of perceived status.

The all-India services, that is, the IAS, the IPS, the IFoS, and possibly the proposed Indian Skill Development Service, are services to encourage national integration and young people interested in them must expect and be expected to serve anywhere in the country. They should not expect or be expected to serve in that part of the country to which they “belong” (their home state) but must go elsewhere.

No State preference should be asked for or entertained at all.

If they want to serve primarily or only in their home States, their State service is the appropriate opportunity for them. This will automatically reduce the number of candidates to those serious about public service anywhere in the country – a national perspective, and national integration – rather than their home area – a parochial perspective, and provincialism.

State allocations should be done by a transparent draw (the home State specifically excluded) and, for these truly to be all-India services, those selected must serve in whichever Indian State the draw decides for them.

What has been described as “legitimate concerns regarding the comparability of marks across the smorgasbord of optional subjects” can be dealt with either by reducing the number of Optionals or eliminating them entirely, which is what the UPSC prefers.[14] Presumably this is because removing the smorgasbord table is the easiest way out for the UPSC, but it is really is dumbing down the examination. It can also be dealt with by restricting the range and type of Optionals, and reducing the lakhs of applicants for the 24 services together to more manageable numbers for separate sets of services.

The CSE list presently offers 25 academic subjects plus 23 literatures – and the impossibility of comparable marking across 48 subjects is obfuscated by claiming an elaborate evaluation procedure involving a hierarchy of examiners and checkers and sample checking, cross-checking and re-checking of answer sheets that nevertheless results in the kind of politics and gross unfairness noted in an earlier essay.

Instead, the optional subjects should be restricted to a choice of two from amongst a restricted number (five?) that are directly relevant to each set of services.[15]

Effort should be made to minimize overlapping of optional subjects across the different sets. Subjects offered should be updated periodically to include new disciplines of practical relevance to our country’s security, development and progress, replacing those which are no longer a priority.

Because there will be fewer candidates, and fewer subjects and, therefore, that many fewer answer sheets to correct, and there will be the facility for candidates to check their corrected answers, it follows that examiners can be expected to be more conscientious in their evaluations.

In effect, what is being proposed is a common preliminary examination (now “qualifying examination”), a common general studies examination (now “preliminary examination”), and specialized services-oriented higher examinations (now “main examination”). This pattern is already somewhat in place with the CSE + Indian Forest Service.

Young people are thus not being denied opportunities; they are only being required to be specific about matching their aptitude and ability to particular choices. A square peg must recognize its squareness and be matched by the UPSC to a square hole, not try to squeeze itself or be squeezed by the UPSC into any of 24 very different holes.

The clubbing suggested below is of the 24 CSE and some related services. There is no reason why sets cannot be expanded to include other non-Defence services to which the UPSC recruits annually, provided they are broadly comparable functionally.

(a) There are the accounts services which can be a set – the Indian Audit and Accounts Service, Group ‘A’; the Indian P & T Accounts & Finance Service, Group ‘A’; the Indian Defence Accounts Service, Group ‘A’; the Indian Civil Accounts Service, Group ‘A’; and the Indian Railway Accounts Service, Group ‘A’. No interview needed.

(b) Different in focus (“economics services”?) are the Indian Trade Service, Group ‘A’ (Gr. III) and perhaps the Indian Corporate Law Service, Group “A” which could be clubbed with the Indian Economic Service and the Indian Statistical Service? Possibly no interview needed.

(c) The Indian Revenue Service (I.T.), Group ‘A’ and the Indian Revenue Service (Customs and Central Excise), Group ‘A’ have public dealings (of a regulatory kind) and so need interviews. They become a separate set. Else they may be fitted in with the accounts services or the economics services.

(d) What professional reason is there for not having common Optionals for the Indian Police Service; all the Central Armed Police Forces (CRPF, BSF, ITBP, SSB, CISF, NSG, RPF); the “Post of Assistant Security Commissioner in Railway Protection Force, Group ‘A’”; the Delhi, Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep, Daman & Diu and Dadra & Nagar Haveli Police Service, Group `B’; and the Pondicherry Police Service, Group ‘B’? Interview needed.

(e) The Indian Ordnance Factories Service, Group ‘A’ (Assistant Works Manager, Administration); the Indian Railway Traffic Service, Group ‘A’; and perhaps the Indian Defence Estates Service, Group ‘A’ could make a set, that could possibly be connected to the Indian Engineering Services. Interview needed.

(f) A set can be formed of the Indian Railway Personnel Service, Group ‘A’; the Armed Forces Headquarters Civil Service, Group ‘B’ (Section Officer’s Grade); the Delhi, Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep, Daman & Diu and Dadra & Nagar Haveli Civil Service, Group ‘B’; and the Pondicherry Civil Service, Group ‘B’. Interview needed.

(g) Of the current CSE list, that leaves the IFS, the IAS, the Indian Postal Service, Group ‘A’, and the Indian Information Service (Junior Grade), Group ‘A’. There may also be the new Indian Skill Development Service. All need interviews. These do not readily get clubbed with any of the other services and may need main examinations of their own but, if we look to function and not (colonial) status, the IAS, IPoS and IIS (and ISDS) are all services that functionally require regular interaction with the public in a developmental sense (as, in a way, the IFS and IFoS do too) and so can be clubbed together, just as all the police services also require interaction with the public but their function is regulatory and so those are clubbed together. If the IFS is included amongst the “development services”, there was a time when, the IAS and IFS being clubbed together, candidates who opted for both were, for the same interview, marked separately for the two. So, now a candidate opting for the IFS as well as the other development services could be given marks separately in assessment of their potential for the IFS.

Yet none of this will work unless the UPSC itself works differently, unless its paper setters, examiners, interviewers, and members (especially the members!) comprehend that:-

– they are part of the Union Public Service Commission (Sangh Lok Seva Aayog)

– they are to recruit young people to serve the public, and not recruit young people who expect the public to serve them

– the selection process does not need to be attuned to India’s development vision; the process is to select persons attuned to India’s development vision

– it would not be counterproductive to not recalibrate the examination in line with the current techno-managerial imperatives of the Indian state, but it would be counterproductive not to recalibrate the examination in line with the current human-aspirational imperatives of the Indian people

– to borrow a phrase used by a very senior babu, it is not about “creating human capital for development”, but about creating development capital for humans.[16]

Look at the biodata of the members of the UPSC.

UPSC Chairman Deepak Gupta

How much is about the really interesting things they have achieved for the lok, done as lok seva, about karna? And how much about the chairs they have sat in, about status, about banna?

How much in their biodata – and professional record – reflects what the UPSC itself prescribes – in the “ethics” syllabus! – as “aptitude and foundational values for Civil Service, integrity, impartiality and non-partisanship, objectivity, dedication to public service, empathy, tolerance and compassion towards the weaker-sections”?

If the mantra for aspiring public servants is to be kuchh banne ke sapne mat dekho kuchh karne ke dekho apne aap kuchh na kuchh ban jaoge, then the mandate for the UPSC is to select for karna, not for banna.

But the UPSC must then first reform itself before it can re-form others. Its own mind-set must change. And getting that mind-set to change, alas, does not appear to be within the mandate of the Baswan Committee.

Notes

- http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Expert-panel-mulls-separate-UPSC-exam-for-each-services/articleshow/49144856.cms

- Yatha raja, tatha prashasan – http://www.vijayvaani.com/ArticleDisplay.aspx?aid=1186 ; The Indian administration is still `yatha raja’- http://www.vijayvaani.com/ArticleDisplay.aspx?aid=2744 ; The UPSC is yatha our raja – dishonest! – http://www.vijayvaani.com/ArticleDisplay.aspx?aid=2878 ; Yatha naya raja, tatha naya prashasan? – http://www.vijayvaani.com/ArticleDisplay.aspx?aid=3231.

- See http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/a-test-for-a-new-time/ and opening section of http://www.firstpost.com/india/upsc-row-are-the-exams-even-equipped-to-choose-the-perfect-bureaucrat-1655313.html. Not a single coaching centre is known to have closed down for lack of business after the 2013 changes, and in 2015 they are flourishing more than ever. Indeed, there even has arisen coaching in CSE-appropriate answers for the “ethics” paper! Any intelligent and motivated candidate will strategise for success, will try to “game the system”. The UPSC has been working as an employment agency for government jobs. All candidates know this. Even the government recognizes this, so it fosters coaching centres, such as the one in the Jamia Millia Islamia, to feed the UPSC.

- The UPSC can be inspired by the PMO – http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31816&articlexml=ALL-IN-A-DAY-01102015004018.

- It is bad enough that the papers set in English are in what may be called unstandardised Indian English, but the translation errors are inexcusable. Thus “painted stork” is literally “chitrit balaak” though both Salim Ali and GOI give “janghil”. Likewise, “common myna” is “sadhaaran maina” instead of “desi maina” given by Salim Ali and the IISc, and “black-necked stork” becomes “kali gardan wala saaras” instead of “loharjang” or “loha sarang” by Salim Ali and “kutung” by GOI. Then “steel plant” becomes “lohe ka paudha”, “land reforms” becomes “arthvayvastha sudhar”, “ multi-brand retail” is “bahumakra khudra vyapaar”, and “panacea” is “sarvopachar”, and worse – http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31816&articlexml=A-Bitter-Language-Divide-03082014016009. If the Hindi questions are wrongly worded, the options to tick become incorrect, there is negative marking, and so Hindi-medium candidates are at a double disadvantage.

- “A person is functionally literate who can engage in all those activities in which literacy is required for effective functioning of his group and community and also for enabling him to continue to use reading, writing and calculation for his own and the community’s development” – https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=1536 . For “community”, read “country”.

- Dropping the essay and the ethics papers also eliminates two major areas of examiner bias, that candidates clearly recognize. High-rank successful candidates readily (and lucratively?) tie up with coaching centres to publicise gaming strategies. Here is some advice from the most-recent first-ranker who clearly understands the politics in UPSC evaluation – “It is better not to pick up such questions [feminism] in essay / ethics, if you’ve option to answer another question. Because you don’t know the gender of the evaluator”, and she gives explicit and detailed advice on how to “game the system” – http://mrunal.org/2015/08/upsc-ias-topper-ira-singhal-mains-answer-writing-ethics-essay-notes.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+CivilServiceExam+%28Civil+Services+Exam%29#43.

- http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/abolishing-interviews-govt-to-start-identifying-posts/.

- http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31816&articlexml=Dont-ask-me-that-question-29082014252005!

- Instances of interviewer bias can easily be accessed from candidate blogs in the public domain. Numerous instances have been given in the earlier essays. Hem Chandra Gupta is rude and abrupt, rants at IITians, and addresses candidates as if they are students in his classroom – “You’re way off the mark…. I’m not impressed….We’re very disappointed in you…It’s an absurd answer….You don’t even know this?” What is tragic is the pronounced anti-Hindi bias. Even Hindi-speaking Gupta and Vinay Mittal tell Hindi-medium candidates to use English. The worst now is P Kilemsungla whose hostility to Hindi is open and blatant. She told one candidate that she couldn’t interview him because she didn’t know Hindi, and ignored him in his interactions with the other panelists. With another, a “namaste” on entering met a curt rebuff – “Speak in English”. It is verboten for an Indian in India seeking public service in India to say “namaste”? The irony is that when Kilemsungla absented herself to go to the toilet, the panelists switched to Hindi. And this was when he was asked about his work with lepers, which he explained fluently and she missed entirely. As soon as she returned, it was back to “speak in English”. Because he needed time to formulate technical-question responses in English, they assumed he didn’t know the answers and condescendingly said they’d ask him easier questions, without understanding he’d need to think out the technical words in English for those too!

- All these ratios are the current practice.

- See note 4 at http://www.vijayvaani.com/ArticleDisplay.aspx?aid=3231.

- See note 9 at http://www.vijayvaani.com/ArticleDisplay.aspx?aid=2744.

- http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/a-test-for-a-new-time/.

- “areas such as governance, polity, international relations, security, technology, economic development, ecology and biodiversity, which are also not easily amenable to cramming” – http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/a-test-for-a-new-time/. For example, for the Optionals for the set of police services, candidates select two from amongst Criminal Law & Criminal Justice, Internal Security, Digital & Cyber Security, Human Rights – Law & Practice, and Police Administration & Reform as the five Optionals.

- http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/a-test-for-a-new-time/ ; http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/students-attend-convocation-in-traditional-attire-at-uoh/article7714542.ece