This essay has been written with specific reference to The Clasp of Civilisations (2015) by Richard Hartz, published by Nalanda International, and Nationalism, Religion, and Beyond (2005), a compilation of Sri Aurobindo’s writings on Politics, Society and Culture, edited by Peter Heehs.

I was rather disappointed after reading The Clasp of Civilisations by Richard Hartz because I expected from him a better understanding of Hinduism than most Western scholars.[i] The book starts off well with a sense of universality in spiritual matters which justifies the title, but gets caught halfway through with the usual antipathy towards Hinduism that is so common among secular scholars of India. The chapter on Vivekananda’s famous address in the Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in September 1893 is indeed well-written and the circumstances of the historic event depicted in a most interesting manner with an undercurrent of humour. But the chapter on Hinduism titled “Untold Potentialities: Jawaharlal Nehru, Sri Aurobindo and the Idea of India”, in which Nehru is elevated into a spiritual figure and Sri Aurobindo converted into a secular icon, shows the fundamental flaws of Richard’s scholarship. One immediately gets the impression of encountering one more Hinduphobic armchair scholar, who meticulously builds his arguments on the works of other Hinduphobic scholars who also have never empathised with Indian culture. Ironically, Richard Hartz has studied the Vedas and is an expert in Sanskrit, but this only shows that mere scholarship does not open the gates of spiritual comprehension. After all, Peter Heehs, his colleague, did the same, wasting forty years of research on Sri Aurobindo and producing such a hostile biography that the disciples of Sri Aurobindo had to go to the Court to take him to task. But let us come back to Richard Hartz who could have easily come to his own conclusions instead of following the path of Peter Heehs with regard to Hinduism, or what is in fact the path of leftist secular scholars of India and abroad which Peter Heehs himself follows faithfully for the sake of his academic career. After all, for him academic success is more important than stating the fundamental truth of Hinduism!

The most uncorroborated conclusion, which is literally taken as an assumption or a fait accompli by Richard Hartz in this book, is the reprehensible and obnoxious character of the “Hindu Rashtra”. This criticism applies not only to him but to all the leftist and secular scholars as well and I, who personally never had any RSS connections, actually had to go to these websites to check what was so horrifying about it and found practically nothing, apart from the expression of legitimate fears over Christian conversions and the rise of Muslim fundamentalism in India. Read the free books available on these sites on the so-called unmentionable communal leaders such as Dr. Hedgewar, Golwalkar and Savarkar, and you will actually find them quite edifying and liberal in their disposition towards other communities who hardly reciprocate the goodwill shown towards them. Take for instance the case of our present Prime Minister himself – what has he done to the exclusive benefit of Hinduism as such? Hardly anything! In fact many Indians who expected a national resurgence of their culture have been deeply disappointed by his inaction on this front. Yet not a single opportunity is lost to call him a communal politician with the hidden agenda of forcing Hinduism on other religious communities of India. Take Hinduism itself for that matter – is there any real threat of Hindus imposing it on other religious groups? I think there is hardly any, because Hinduism has so many diverse sects and forms that it would be difficult to decide in the first place which of them express its core values, and one would be finally left with the option of each following his own faith and letting others free to follow their own. This is in fact what has happened in India because of the inherent inclusivity of Hinduism. I would dare say that even the large-scale conversion of Hindus into other religions in India is partly due to the innate catholicity of the Hindus themselves, and not because of the discrimination the lower castes have had to face from the upper castes, as repeated ad nauseam by leftist scholars! So the only conclusion I can draw is that Hinduphobia, or the deeply embedded fear of the Hindu Rashtra in secular scholars, is due to political reasons and not cultural apprehension.[ii] Just read the newspapers daily and you see how frequently opportunistic secular politicians support religious fundamentalism, or how the latter actually hides behind secularism and uses its very neutrality to strengthen itself. Mark how obstinately leftist scholars (who have dominated India from the early seventies) reinforce this notion time and again for totally other considerations than producing objective scholarship! Richard Hartz unfortunately follows this well-beaten path of the secular left with unthinking devotion and faith, and is thus totally out of sync with the spiritual ethos of Indian life.

The second objection that I make is also general and particular, while it appeals to simple commonsense. When leftist academics come up with adverse comments on Hindu culture under the garb of objective scholarship, don’t they realise that they are distancing themselves from at least 80 % of the population of India which is deeply religious? But I suppose this is why the Left parties have politically failed in India. So when Peter Heehs and Richard Hartz make the grand announcement that Sri Aurobindo distanced himself from Hinduism, and the Hindu culture that was incorporated in his Ashram was a concession to his Hindu disciples, they are also alienating themselves from 95 % of the devotees and disciples of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother! Alienating themselves from others for the sake of spiritual truth would still have been appreciated, but to cleverly quote half sentences and stray quotations without giving the full context, and almost bending backwards to prove one’s point can hardly be justified. This is exactly what Peter Heehs and Richard Hartz have done, and a group of Sri Aurobindo scholars are now doing to justify their hatred of Hinduism. Peter Heehs goes to the ridiculous extent of stating that Sri Aurobindo made concessions to his Hindu disciples by stressing on the importance of the Divine Mother, or mentioning the role of Sri Krishna in his own Yoga.[iii] Even accepting the devotion and adoration with which his disciples approached him is perceived by Peter Heehs as mere adulation which could have been avoided by Sri Aurobindo. I wonder what would remain of Sri Aurobindo’s Yoga, or for that matter of any Yoga, if the essential means and facilitators of spiritual union with the Divine are taken away from the seekers.

To make matters worse, Richard has to bring in a dichotomy in Sri Aurobindo’s life in order to reconcile his thesis of Sri Aurobindo rejecting Hinduism in his later days. The revolutionary Sri Aurobindo, who wrote the Bande Mataram and the Karmayogin in which articles on the spiritual greatness of Hinduism abound, has to be thus distanced from the Sri Aurobindo who later wrote about the Supramental Manifestation in The Life Divine. By quoting one autobiographical remark [iv] of Sri Aurobindo on having gone far beyond in his spiritual consciousness and knowledge in his Pondicherry days from the time when he was in revolutionary politics, Richard conveys the impression that Sri Aurobindo was then a spiritual novice[v], and his early views on Hinduism are therefore obsolete. But did Sri Aurobindo later contradict what he wrote earlier? And if he did where did he say so? The said remark is also general in nature and has no specific reference to Hinduism at all! Moreover, Sri Aurobindo had a number of major spiritual experiences in the early period, so he could hardly be considered a spiritual novice then. And what about his nuanced and comprehensive view in the Karmayogin days on the various forms of Hinduism, which distinguish between the “lower and higher Hinduism”, and within higher Hinduism “the sectarian and unsectarian”? These are some of the questions that have been left deliberately unanswered by Richard Hartz who quotes only those passages that support his thesis.

Another argument developed by Peter Heehs in support of this scission in Sri Aurobindo’s life is that his early views on Hinduism were expressed in the context of the repressive colonial regime and the Indian independence movement in which he played a major historical role. The famous Uttarpara speech, for which leftist historians have accused Sri Aurobindo to be the founder of Hindu nationalism and therefore of present day Hindu communalism, has been taken by Peter Heehs as an expression of patriotism and not of spiritual nationalism which it obviously is, when seen in the larger context of Sri Aurobindo’s concept of the nation soul.[vi] Sri Aurobindo and the revolutionary leaders of his period were awakening the soul of India, and spirituality was the very foundation of their patriotism.[vii] They were not merely fooling the subjugated people of India by emotionally appealing to an “idea of India” (so fashionable now) which was not there until the British came and cobbled it together. According to Sri Aurobindo, the Indian nation soul was formed many centuries back and was behind the cultural and psychological unity of its people. It was only the political body that could never be created due to its inherent fissiparous tendencies created by the spiritual principle which was supposed to unite India, but failed to do so because of the great difficulty of such an experiment in human unity.[viii] The British therefore only provided the political body to what was already one in spirit and temperament, though they left it ruptured into several sub-nations.

The position taken by Peter Heehs and Richard Hartz is that Sri Aurobindo has been hijacked by right wing Hindu nationalists and has been therefore wrongly criticised by left wing secular historians such as Romila Thapar and Bipan Chandra. This intellectual exercise of saving Sri Aurobindo from being appropriated by the right wing while defending him from critical left wing scholars has been the subject of an article by Peter Heehs titled, “The uses of Sri Aurobindo: mascot, whipping-boy, or what?” A similar exercise has been undertaken by Richard Hartz in his book under the sub-heading “Hindu Nationalism and the Idea of India” (pp. 140-47) in perfect copy cat style of Peter Heehs’s arguments. Because Left wing historians have based their accusation of Sri Aurobindo being communal on the speeches and articles of his revolutionary days, it was technically necessary for Peter Heehs & Richard Hartz to prove that Sri Aurobindo had moved far beyond his early views on Hindu nationalism and distanced himself from them in his latter days. This has been primarily done on the basis of three letters written by Sri Aurobindo to Dara, a Muslim disciple residing in the Ashram in the thirties, and a few other quotations from his major works. Ironically, even his early articles in the Karmayogin (such as the one objecting to the formation of the Hindu Sabha in 1909[ix]) have been used to prove their point, which precisely makes a sharp distinction between the early pro-Hindu nationalist phase of Sri Aurobindo’s life and the universal Sri Aurobindo of the Pondicherry period when he supposedly rejected Hinduism. This goes to show what a futile exercise it is to separate Sri Aurobindo’s life into two distinct periods with very little connection between them. Sri Aurobindo certainly progressed far beyond what he had attained in his early days of Yoga, and worked out later the supramental path which can be considered new to Hinduism, but he never rejected the essential spiritual truths of Hinduism on which he based his Yoga and philosophy.

It is true that Sri Aurobindo accepted the spiritual truth behind all religions and not only of the Hindu religion, but that should not deprive the role of higher Hinduism in the spiritual future of mankind, especially when he said that it was “the richest expression” of the spiritual essence of all religions. He wrote in The Foundations of Indian Culture that India is “the meeting-place of the religions and among these Hinduism alone is by itself a vast and complex thing, not so much a religion as a great diversified and yet subtly unified mass of spiritual thought, realisation and aspiration.”[x] Yet Peter Heehs & Richard Hartz pick out Hinduism as a black sheep that does not fit with the rest of the herd instead of giving its due credit and place. It is here that you find a deep rooted racial bias against Hinduism and a rather immature understanding of it. It is like saying, “Look, the other religions to which we belong have totally failed to deliver man, so Hinduism too should fail. We have been disappointed by our respective religions, so you too should be disappointed by your religion! Then only we can all go beyond religion and rise to spiritual heights.” But what if Hindus are not so dissatisfied with their religion because of its inherent universality and freedom to choose one’s own path? And what if many Hindus have turned to Sri Aurobindo without leaving their traditional paths and integrated his Yoga into their lives without feeling any sense of opposition? And what if traditional Yogas have also evolved and modernised themselves to suit the changing times? (I myself know a few people who are earnest followers of Sri Aurobindo and at the same time ardent devotees of Lord Venkateshwara of Tirupati.) Moreover, at the basic level of consciousness where most of us operate, the difference between traditional Yogas and Sri Aurobindo’s Yoga of transformation is mostly irrelevant in actual practice, though there is scope for considerable scholarly dispute at the intellectual level.

There is often a tendency among the exponents of Sri Aurobindo’s Yoga to grandly call for universal spirituality and glibly condemn Hinduism in the same breath without taking into account the ground realities of our present life. For a condemnation of Hinduism without having anything to replace it practically except for The Life Divine or The Synthesis of Yoga of Sri Aurobindo, which you can barely comprehend or spiritually practise, ends up only in creating a spiritual vacuum. A similar kind of facile denunciation of all religions (with Hinduism listed in all caps) has also been in vogue among some of the followers of Sri Aurobindo without realising that this attitude will soon deprive them of the very Gurus they hold in such great esteem. For Sri Aurobindo and the Mother are now themselves considered among the religious figures of Hinduism, despite their own aversion to religion. After all, it is mostly the disciples who create religion for their own convenience than the Gurus who are responsible for it. An anti-Guru tirade is also considered avant garde spirituality even as you fall easy prey to the tech talk and mumbo jumbo of new-age Gurus who look more for commercial success than the honest propagation of spiritual well-being. I would certainly propose the intervention of plenty of common sense in these matters than rely upon the conclusions of half baked scholars of the above kind.

Again, in order to disprove some of Sri Aurobindo’s frankly negative remarks on Muslim fanatics (which is taken as stark and shocking evidence of Hindu communalism by leftist scholars), Richard Hartz puts up an elaborate argument to destroy the credibility of the Evening Talks with Sri Aurobindo recorded by A.B. Purani and Nirodbaran. This is tantamount to destroying the mountain for the mole that is hiding underneath, or to carpet bomb a city to kill one terrorist. For instead of doubting the few anomalies that are there in the Evening Talks due to the obvious difficulty of recording them accurately, and checking these out against other authentic sources, Richard Hartz rejects them in toto[xi] to buttress the theory that Sri Aurobindo was not pro-Hindu and therefore never anti-Muslim. But Sri Aurobindo was indeed never anti-Muslim, though he made some caustic remarks on Muslim fanaticism. For that matter, he was also highly critical of Gandhi and his policies. The conversations with his disciples were meant to be private and therefore he was all the more free to air his views, which he would not have done in a written statement meant for the public. One should know that Sri Aurobindo eschewed politics in Pondicherry so that his presence would not embarrass the French Govt which had given him refuge. Thus the fact that his verbal remarks on Muslim fanaticism and Gandhi do not match any public statements of that time, can be simply attributed to political discretion than an unreliable notation of the Talks. Incidentally, Richard Hartz himself uses the very same Evening Talks recorded by A.B. Purani to prove that “Bande Mataram”, the national song, is not a religious but a national song (see footnote 51 on page 149).

Finally, there can be no real progress in this debate over Sri Aurobindo’s views on Hinduism, unless you fix the exact definition of it in his own words. Otherwise, clever Hinduphobic scholars such as Peter Heehs will keep jumping up and down, and from right to left of the various shades and degrees of Hinduism for the sake of winning an argument than coming to a sober conclusion on Sri Aurobindo’s views on Hinduism. Or, even if they compile Sri Aurobindo’s views on Hinduism and Indian nationalism, they would snip the quotations where they precisely should not be, and constantly make corrective remarks to mislead the readers from the plain sense of Sri Aurobindo’s words. Peter Heehs has compiled his Nationalism, Religion, and Beyond (2005) exactly in this way. In this compilation, in order to disconnect spirituality from nationalism in the famous Uttarpara speech delivered by Sri Aurobindo after coming out of Alipore jail, Peter Heehs neatly snips out[xii] the most inspiring experience of Sri Krishna in jail, which Sri Aurobindo later mentions as the realisation “of the cosmic consciousness and of the Divine as all beings”.[xiii] The motive of Peter Heehs, in what is called an active omission, is to keep spirituality out of politics and to actually defend Sri Aurobindo (though in the wrong way) from the standard communal accusation of leftist historians. Spirituality and religion are taboo for the Left, for, according to them, they necessarily foment communalism. By bringing religion into politics or hearkening back to Hindu spiritual traditions in public life, as Sri Aurobindo and his political associates did in the early phase of the Indian freedom struggle, united the Hindus but permanently distanced the Muslims and other minorities from them. Therefore Sri Aurobindo and his associates have been accused of laying the foundation of communalism in modern India. This is the standard and stale argument of the Left, which will perhaps never realise that Hindus can never be deprived of their spiritual ethos.

One of the best descriptions of the multiple layers of Hinduism is the following passage written by Sri Aurobindo around 1910-12. I quote it at length because I have based myself on this description to counter the notion that Sri Aurobindo rejected higher Hinduism in his later days. (Those who find it too long can skip it and go straight to my summarisation below.)

There are two Hinduisms; one which takes its stand on the kitchen and seeks its Paradise by cleaning the body; another which seeks God, not through the cooking pot and the social convention, but in the soul. The latter is also Hinduism and it is a good deal older and more enduring than the other; it is the Hinduism of Bhishma and Srikrishna, of Shankara and Chaitanya, the Hinduism which exceeds Hindusthan, was from of old and will be for ever, because it grows eternally through the aeons. Its watchword is not kriya, but karma; not shastra, but jnanam; not achar, but bhakti. Yet it accepts kriya, shastra and achar, not as ends to be followed for their own sake, but as means to perfect karma, jnanam and bhakti. Kriya in the dictionary means every practice which helps the gaining of higher knowledge such as the mastering of the breath, the repetition of the mantra, the habitual use of the Name, the daily meditation on the idea. By shastra it means the knowledge which regulates karma, which fixes the kartavyam and the akartavyam, that which should be done and that which should not, and it recognises two sources of that knowledge,—the eternal wisdom, as distinct from the temporary injunctions, in our ancient books and the book that is written by God in the human heart, the eternal and apaurusheya Veda. By achar it understands all moral discipline by which the heart is purified and made a fit vessel for divine love. There are certain kriyas, certain rules of shastra, certain details of achar, which are for all time and of perpetual application; there are others which are temporary, changing with the variation of desh, kal and patra, time, place and the needs of humanity. Among the temporary laws the cooking pot and the lustration had their place, but they are not for all, nor for ever. It was in a time of calamity, of contraction under external pressure that Hinduism fled from the inner temple and hid itself in the kitchen. The higher and truer Hinduism is also of two kinds, sectarian and unsectarian, disruptive and synthetic, that which binds itself up in the aspect and that which seeks the All. The first is born of rajasic or tamasic attachment to an idea, an experience, an opinion or set of opinions, a temperament, an attitude, a particular guru, a chosen Avatar. This attachment is intolerant, arrogant, proud of a little knowledge, scornful of knowledge that is not its own. It is always talking of the kusanskars, superstitions, of others and is blind to its own; or it says, “My guru is the only guru and all others are either charlatans or inferior,” or, “My temperament is the right temperament and those who do not follow my path are fools or pedants or insincere”; or “My Avatar is the real God Himself and all the others are only lesser revelations”; or “My ishta devata is God, the others are only His partial manifestations.” When the soul rises higher, it follows by preference its own ideas, experiences, opinions, temperament, guru, ishta, but it does not turn an ignorant and exclusive eye upon others. “There are many paths,” it cries, “and all lead equally to God. All men, even the sinner and the atheist, are my brothers in sadhana and the Beloved is drawing them each in His own way to the One without a second.” But when the full knowledge dawns, I embrace all experiences in myself, I know all ideas to be true, all opinions useful, all experiences and attitudes means and stages in the acquisition of universal experience and completeness, all gurus imperfect channels or incarnations of the one and only Teacher, all ishtas and Avatars to be God Himself.[xiv]

Sri Aurobindo distinguishes between lower and higher Hinduism, the first “which takes its stand on the kitchen and seeks its Paradise by cleaning the body,” and the latter “which seeks God, not through the cooking pot and the social convention, but in the soul”. He makes a further distinction within higher Hinduism, the “sectarian and unsectarian”. The first, that is, higher but sectarian Hinduism, limits itself to “an idea, an experience, an opinion or set of opinions, a temperament, an attitude, a particular guru, a chosen Avatar” and is intolerant of “knowledge that is not its own”. The second, that is, higher unsectarian Hinduism, embraces all experiences in itself, “knows all ideas to be true, all opinions useful, all experiences and attitudes a means and stages in the acquisition of universal experience and completeness, all gurus imperfect channels or incarnations of the one and only Teacher, all ishtas and Avatars to be God Himself.” How could Sri Aurobindo have rejected higher unsectarian Hinduism for which he has so much praise and admiration? And what would be so reprehensible and inacceptable about it even to non-Hindus?

But Peter Heehs plays with these different layers of Hinduism like on a keyboard in order to prove that Sri Aurobindo rejected Hinduism. When Sri Aurobindo decries Hinduism in the sense of lower Hinduism (meaning outdated conventions and rituals), or in the sense of higher but sectarian Hinduism (meaning the different sects of Hinduism which limit themselves to particular aspects of the Divine), he jumps up and says, “Look, Sri Aurobindo has rejected Hinduism!” And when Sri Aurobindo speaks of the Sanatana Dharma in the sense of unsectarian Hinduism or universal spirituality, he takes it in the sense of sectarian higher Hinduism and says, “If Sanatana Dharma is truly a universal religion, how can it be part of Hinduism?”[xv] Richard Hartz follows Peter Heehs’s cue and adopts the same method of semantic deception and presenting decontextualised passages from Sri Aurobindo’s works to prove this point.

What however can be admitted is that Sri Aurobindo did later go beyond any of the well-known realisations and yogic methods of Hinduism. His Integral Yoga with the ultimate goal of the supramental transformation of man can surely be considered a quantum leap in the spiritual history of the world, and not merely of India. But he still linked his Integral Yoga with the spiritual essence of Hindu traditions without always mentioning the old terms and often creating his own vocabulary to express his yogic concepts. The supramental Yoga disappears into unreachable and inconceivable heights, but the preliminary stages described in his letters to his disciples, such as the discovery of the soul (atma or chaitya purusha in traditional Yogas), or the realisation of the Self (Atman is perhaps the most frequently used term in Indian Yoga), or the concept of the Divine Power (Shakti), or the necessity of sexual transformation (brahmacharya), are all familiar notions to people in India. The fact that Sri Aurobindo does not use the words “Hindu” or “Hinduism” in The Life Divine has been triumphantly produced by Richard Hartz as additional proof of Sri Aurobindo having rejected Hinduism. But there is no dearth of references in the Life Divine to the Veda, Vedanta and the Upanishads. The very fact that every chapter in it is headed by quotations from ancient Hindu scriptures, and the very respect shown to the “Aryan forefathers”, “Vedic Rishis”, and “ancient sages” show that Sri Aurobindo took the general conceptual framework of Hindu philosophy to express his own innovative spiritual world view.

But how do we reconcile this position with Sri Aurobindo’s highly critical remarks on Hinduism which have been exploited to the hilt by biased Hinduphobic scholars? It is worthwhile focusing our attention on three of the most negative statements made by Sri Aurobindo in his letters to a Muslim disciple in 1932 and explaining their full context. I begin by quoting first the decontextualised sentence which has created so much misunderstanding with regard to Sri Aurobindo’s views on Hinduism:

If this Asram were here only to serve Hinduism I would not be in it and the Mother who was never a Hindu would not be in it.[xvi]

This most scathing remark on Hinduism was made in a reply to Dara, a Muslim disciple of Sri Aurobindo, who grudgingly complained to him that the Ashram had become a Hindu Ashram. He wrote that the attitude of the Hindus of the Ashram was highly discriminatory and patronising towards the Muslims, and there was pressure on him to cease to be a Mohamedan while there was no such compulsion on them to renounce Hinduism, despite the Mother’s official notice in the Ashram saying, “When a man comes here, he ceases to be a Hindu or a Mahomedan.” I quote now the full question of Dara along with the complete reply of Sri Aurobindo so that the reader cannot complain of a decontextualised presentation of documents:

I thought the attitude towards Mahomedans lay in the minds of the people here because of a subconscious influence and I took this to be an ignorance that can be overlooked for the time being. But if Sri Aurobindo also writes like this, I wish to know if the Mahomedan world is a separate block to be dealt with as one deals with strangers, foreigners, almost enemies.

Somehow I have no faith in the creation here being absolutely pure on this point – unless the Mother and Sri Aurobindo intervene. There is a terrible hatred, disgust, ignorance and suspicion against Mahomedans and a sense of infinite superiority and patronism when dealing with them. From the ordinary Mahomedan point of view, I would say that this is a most dangerous place in the world, the depth of which cannot even be fathomed.

I wish also to ask this: The Mother has often issued notices saying, “When a man comes here, he ceases to be a Hindu or a Mahomedan etc.” Though there is sufficient pressure on the Mahomedans to cease to be Mahomedan, does anybody cease to be a Hindu? Is the idea even believed by any Hindu sadhak? So certain is everybody in its not being true that there is hardly any hope of such a thought ever entering the mind. Under these circumstances, God alone knows if it is right or sensible for me to live on and see the ruin without doing anything to bring in the Mohamedan influence here. When I surrendered, I had not ceased to be a Mahomedan as I did afterwards.

If there is anybody in this Asram who is a Hindu sectarian hating Mahomedans and not opening to the Light in which all can overcome their limitations and in which all can be fulfilled (each religion or way of approaching the Divine contributing its own element of the truth, but all fused together and surpassed), then that Hindu sectarian is not a completely surrendered disciple of Sri Aurobindo. By his narrowness and hatred of others he is bringing an element of falsehood into the work that is being done here.

When I spoke of the outside world, I meant all outside, including the Hindus and Christians and everyone else, all who have not yet accepted the greater Light that is coming. If this Asram were here only to serve Hinduism I would not be in it and the Mother who was never a Hindu would not be in it.

What is being done here is the preparation of a Truth which includes all other Truth but is limited to no single religion or creed, and this preparation has to be done apart and in silence until things are ready. It is in that sense that I speak of the rest of the world and all its component parts as being the outside world — not that there was nothing to be done or no connection to be made; but these things are to be done in their own proper time.

Do you tell me that all the people here show the spirit you speak of against the Mahomedans or are you generalising from particular cases? If it is as you say, I am quite ready to intervene to put a stop to it. For such a spirit would be entirely opposed to the Truth I am here to manifest.[xvii]

17 November 1932

Sri Aurobindo refers in the very first sentence of his reply to sectarian Hindus hating Mahomedans, so it was sectarian Hinduism that had no place in his Ashram. And if it did exist in his Ashram against his own wishes, as the Muslim disciple was insinuating him of, he says the Mother and he would not be in the Ashram. He does not refer to unsectarian higher Hinduism at all! It was also wise not to mention Hinduism even in the higher sense, for it would have been immediately misinterpreted by non-Hindus, as the Muslim disciple had precisely done. The third paragraph explains the universal spiritual basis of Yoga in the Ashram, “What is being done here is the preparation of a Truth which includes all other Truth but is limited to no single religion or creed.” How is this different from the wider unsectarian Hinduism or the sanātana dharma as he described it in the Karmayogin, which I quote below? Note the text in bold letters.

The world moves through an indispensable interregnum of free thought and materialism to a new synthesis of religious thought and experience, a new religious world-life free from intolerance, yet full of faith and fervour, accepting all forms of religion because it has an unshakable faith in the One. The religion which embraces Science and faith, Theism, Christianity, Mahomedanism and Buddhism and yet is none of these, is that to which the World-Spirit moves. In our own, which is the most sceptical and the most believing of all, the most sceptical because it has questioned and experimented the most, the most believing because it has the deepest experience and the most varied and positive spiritual knowledge, – that wider Hinduism which is not a dogma or combination of dogmas but a law of life, which is not a social framework but the spirit of a past and future social evolution, which rejects nothing but insists on testing and experiencing everything and when tested and experienced, turning it to the soul’s uses, in this Hinduism we find the basis of the future world religion. This sanātana dharma has many scriptures, Veda, Vedanta, Gita, Upanishad, Darshana, Purana, Tantra, nor could it reject the Bible or the Koran; but its real, most authoritative scripture is in the heart in which the Eternal has His dwelling. It is in our inner spiritual experiences that we shall find the proof and source of the world’s Scriptures, the law of knowledge, love and conduct, the basis and inspiration of Karmayoga.[xviii]

I quote another passage written in 1919-1921 of the Arya period.

The religious culture which now goes by the name of Hinduism not only fulfilled this purpose, but, unlike certain credal religions, it knew its purpose. It gave itself no name, because it set itself no sectarian limits; it claimed no universal adhesion, asserted no sole infallible dogma, set up no single narrow path or gate of salvation; it was less a creed or cult than a continuously enlarging tradition of the Godward endeavour of the human spirit. An immense many-sided many staged provision for a spiritual self-building and self-finding, it had some right to speak of itself by the only name it knew, the eternal religion, sanātana dharma.[xix]

As we can see, there is a remarkable similarity of his concept of higher unsectarian Hinduism (or the sanātana dharma) with the universal basis of spirituality that he founded his Integral Yoga upon. The only difference is in the connotation of the word religion, which is used in the positive sense of spirituality in the above two passages from the early period, as opposed to the negative sense it acquired later when Sri Aurobindo clearly distinguished it from spirituality. I go to the next damaging quote on Hinduism:

On the other hand I have not the slightest objection to Hinduism being broken to pieces and disappearing from the face of the earth, if that is the Divine Will.[xx]

I now quote again the full reply of Sri Aurobindo with the disciple’s question:

If the sadhaks here remain Hindus, which in the end turns out to be their very aim and zest, what an utter fool I would be to allow myself to be changed and trust myself to be worked upon thus.

Again, when Sri Aurobindo writes about what he is going to manifest here, I wonder why such a great thing is partial. Why should that creation be formed in such a way as to exclude Mahomedans from it and put on them an all-round pressure which is experienced by nobody else? To give up one’s past and forget it or to try not to think about it is one thing; to go through the humiliation of taking up the way of others is most difficult, almost shameful, and I have lost faith in it.

It is news to me that I have excluded Mahomedans from the Yoga. I have not done it any more than I have excluded Europeans or Christians. As for giving up one’s past, if that means giving up the outer forms of the old religions, it is done as much by the Hindus here as by the Mahomedans. Every Hindu here—even those who were once orthodox Brahmins and have grown old in it,—give up all observance of caste, take food from Pariahs and are served by them, associate and eat with Mahomedans, Christians, Europeans, cease to practise temple worship or Sandhya (daily prayer and mantras), accept a non-Hindu from Europe as their spiritual director. These are things people who have Hinduism as their aim and object would not do—they do it because they are obliged here to look to a higher ideal in which these things have no value. What is kept of Hinduism is Vedanta and Yoga, in which Hinduism is one with Sufism of Islam and with the Christian mystics. But even here it is not Vedanta and Yoga in their traditional limits (their past), but widened and rid of many ideas that are peculiar to the Hindus. If I have used Sanskrit terms and figures, it is because I know them and do not know Persian and Arabic. I have not the slightest objection to anyone here drawing inspiration from Islamic sources if they agree with the Truth as Sufism agrees with it. On the other hand I have not the slightest objection to Hinduism being broken to pieces and disappearing from the face of the earth, if that is the Divine Will. I have no attachment to past forms; what is Truth will always remain; the Truth alone matters.[xxi]

17 November 1932

The Muslim disciple is in the same resentful mood as in the previous letter. In fact both letters were written on the same date, 17 November 1932. His objection again is that Mahomedans were being left out of the new creation that was being established by Sri Aurobindo and the Mother. Sri Aurobindo comes down on him like a hammer and ends with the most devastating remark on Hinduism he ever made in his lifetime. This particular reply, when not properly contextualised, will make the Hindu disciples of Sri Aurobindo wince with pain and humiliation and be apologetic of Hinduism, for it would then be a matter of choice between their spiritual Master on one side and their culture and tradition on the other. Hindus, who are not disciples or admirers of Sri Aurobindo, will naturally misconstrue his words and accuse him of being too westernised to understand the true spirit of Hinduism. But it is quite clear that Sri Aurobindo is referring to “the outer forms of the old religions” that have to be given up in his Ashram, which applies to his Hindu as well as non-Hindu disciples. He goes on to enumerate the conventions that his Hindu disciples do not follow in his Ashram – they “give up all observance of caste, take food from Pariahs and are served by them, associate and eat with Mahomedans, Christians, Europeans, cease to practise temple worship or Sandhya (daily prayer and mantras), accept a non-Hindu from Europe as their spiritual director,” namely, the Mother. His objections are therefore to the past rituals and conventions of Hinduism which do not have much value in his Integral Yoga. It is in this context that Sri Aurobindo makes this drastic statement on Hinduism.

If Sri Aurobindo had indeed meant that everything of Hinduism – lower, higher, sectarian and unsectarian – had to be discarded in his Ashram, he would not have qualified his harsh statement with the following sentence in the same letter, “What is kept of Hinduism is Vedanta and Yoga, in which Hinduism is one with Sufism of Islam and with the Christian mystics.” This sentence has been cleverly misinterpreted by Richard Hartz and Peter Heehs as tantamount to Sri Aurobindo’s rejection of Hinduism. They argue that if only the essential truth of all religions can claim to have place in the supramental Truth, then there cannot be any religious identity left in the spiritual future of mankind as envisaged by Sri Aurobindo. So not only Christianity, Islam and Buddhism will eventually disappear from the face of the earth, but Hinduism also should and will follow suit. But the same argument can be applied to include than exclude all religions, or include each religion insofar as it expresses the essential truth behind all religions, and this actually works out with greater advantage to Hinduism, for, according to Sri Aurobindo, Hindu spirituality is “the richest expression” of this essential truth. I quote below the full text of the last quote:

I can say what to my view is the truth behind Hinduism, a truth contained in the very nature (not superficially seen of course) of human existence, something which is not the monopoly of Hinduism but of which Hindu spirituality was the richest expression. [xxii]

Sri Aurobindo wrote this letter in 1936, four years after his negative statement on Hinduism in 1932. This should set to rest any apprehension or misunderstanding of Sri Aurobindo having turned against or rejected the truth behind Hinduism in his latter days. What he discouraged and rejected, and that too without any vehemence, were the past forms and conventions of Hinduism which had no longer any value in the Integral Yoga practised in his Ashram.

I continue my presentation of documents with one more letter written to the Muslim disciple by Sri Aurobindo on the same date (17 November 1932) as the two letters that have been fully quoted above and explained in detail.

I don’t say that all the people here have this spirit against Mahomedanism, but I cannot think of anyone who cannot get it. Some older sadhaks can detach themselves from it and concentrate on something else, but about others I don’t know. From the Mahomedan point of view, there is sufficient reason to smart on the point. The great praise I got for putting on a dhoti here evidently shows the spirit or barrier or whatever it be.

What has dhoti to do with Hinduism or Mahomedanism? There are thousands of Hindus who never wear it – they wear pyjamas of some kind. Rieu, Arjava, Suchi [three Western disciples] wear dhoti because it is convenient and good for the climate – they do not care one jot for Hinduism.[xxiii]

17 November, 1932

One cannot but smile at the Muslim disciple’s insistence of being looked down upon by the Hindus in the Ashram. His objection is now to the dhoti (a Hindu dress) that he is being encouraged to wear by them. Sri Aurobindo dismisses him by mentioning that the facts are contrary to what he thinks. He says thousands of Hindus wear pyjamas (generally worn by Muslims) and three Westerners in the Ashram, who “do not care one jot for Hinduism” wear dhotis (a Hindu dress) because of the sultry climate of Pondicherry. Moreover, what has dress got to do with religion? Dress has indeed become nowadays a major topic of public discussion on religion, but it only shows the externalities that people generally equate religion with. It was all the more necessary for Sri Aurobindo to therefore dissociate his Ashram from external rituals and conventions that generally define religion in order to emphasise the spiritual content of his Yoga. I come to the last letter under consideration:

I want to ask Sri Aurobindo whether the Ashram is created in such a way that among the communities of this country or the people of other nations, it is only the Hindus who will ultimately profit by it? Do the distinctions of religion and nationality count for much? Does the supramental victory mean the victory of the Hindu religion and culture over others? Will the supramental consciousness come into the body of a man whether or not he subordinates himself to Hinduism?

The Asram has nothing to do with Hindu religion or culture or any religion or nationality. The Truth of the Divine which is the spiritual reality behind all religions and the descent of the supramental which is not known to any religion are the sole things which will be the foundation of the work of the future.[xxiv]

It is again the same jealous Muslim disciple who questions Sri Aurobindo regarding the close connection of Hinduism (as opposed to his own religion) to the Integral Yoga. Sri Aurobindo rebuffs him this time with such a sweeping statement on the Hindu religion that it would have silenced him for good. But Hindu religion has to be taken again (as in the first two letters) in the sense of sectarian Hindu religion and certainly not as unsectarian higher Hinduism. Also Hindu religion or culture is particularly mentioned not because it is less suitable for the supramental Yoga than the other religions, but for the simple reason that the disciple had asked him about it. It is this context that clarifies and mitigates the apparently harsh and drastic statement on the Ashram having nothing to do with Hinduism.

Sri Aurobindo goes on to explain the non-religious and universal spiritual basis of his Yoga and points us to the ultimate descent of the supramental power hitherto unknown to any religion. Again the word religion need not apply here to his concept of higher unsectarian Hinduism or the sanātana dharma, which “unlike certain credal religions” gave itself no name and “set itself no sectarian limits”. But even if we consider the supramental transformation to exceed the limits of unsectarian higher Hinduism, the Integral Yoga that was propounded by Sri Aurobindo in his latter days and practised by his disciples under the guidance of the Mother in the Ashram contained many of the deeper and higher elements of Hinduism.

It is primarily those customs in the Ashram which express bhakti, adoration of and surrender to one’s Guru (so common in India) that have put off some Westerners such as Peter Heehs who concludes that Sri Aurobindo conceded to Hindu practices and customs for the sake of his Hindu disciples,[xxv] despite distancing himself from them in his writings. Ironically, he blames the Mother for it,[xxvi] though she was a French lady coming from a highly cultured European background! Sri Aurobindo nevertheless considered her his spiritual equal and handed over the spiritual and material charge of the Ashram when he retired in November 1926. In the late twenties and thirties when he was corresponding with his disciples from his room, the Mother personally supervised the various departments of the Ashram (such as the Building Construction, the Dining Room, and the Dispensary to name only a few) and conducted the daily meditation and Pranam for the disciples. In this period of joint administration, with the Mother in front and Sri Aurobindo supporting her from behind, all the activities of the Ashram were centred round the Mother with the full approval of Sri Aurobindo. So there cannot be any question of the Mother having introduced Hindu customs such as the Pranam and Prasad distribution against the wishes of Sri Aurobindo! As a matter of fact, the Mother was the best exponent and guide of Sri Aurobindo’s Yoga to say the least, and it is difficult to understand or even practise it without taking her into account.

What however can be said is that Sri Aurobindo and the Mother did start from a clean slate, as it were, of spiritual practices without being encumbered by past forms of Hinduism or any religion whatsoever. They were at the same time not overly fussy of avoiding any of the existing forms, if they proved to be useful means of inner communion with their disciples. Apart from the three (or later four) major Darshans they gave to their disciples and devotees every year, the Mother conducted daily meditations followed by her Pranam to the disciples in the early period of the Ashram. There was a soup distribution by the Mother in the evening (prior to October 1931) in order to impart her spiritual force to the disciples. Flowers acquired symbolic significances and became a very important means of spiritual communication. In the forties and fifties the Mother distributed special blessings on the four Puja days of the Hindu calendar. With the coming of the children to the Ashram and the founding of the Ashram School, Christmas with its spiritual significance was introduced in the Ashram. During this period sports and physical education became a very important part of Ashram life, and for some time meditation and Pranam receded into the background, and some disciples such as Dilip Kumar Roy expressed their alarm and consternation at this secular transformation of the Ashram. Meditation was again reintroduced, and concentration at the Playground in front of the spiritual map of India became a daily feature in the fifties. A groundnut distribution by the Mother also took place in the Playground, ostensibly for the extra nourishment of the School children, but which was obviously a part of her larger action of infusing her spiritual force in all the activities of the Ashram.

What do you make of these various programmes of the Mother? Were they Hindu ceremonies? Yes, the Puja Darshans could be named as such, though they ceased after some time. Celebrating Christmas should then be considered a Christian custom, though the Mother said that Christmas was celebrated as a festival of light long before the birth of Jesus Christ. What about the soup ceremony? Amal Kiran compares it with the sacred rituals of ancient Greece and Egypt. Pranam and collective meditation under the auspices of a spiritual guide or Guru would figure, I suppose, in most religious communities, be they Buddhist or Jain or Hindu or Sufi. But what about the groundnut distribution? Did Mother start here a brand new ceremony or mode of spiritual communion? Our difficulty to label the Mother’s collective activities only shows the rigidity of our mind, by which we would like to make easy classifications for our own convenience than to understand the plasticity and spontaneity with which the Mother acted in the Ashram. Even religion, which Sri Aurobindo and the Mother themselves condemned outright, has to be taken with due qualifications especially with regard to them and the Integral Yoga they have developed for the spiritual future of man. Otherwise we tend to reject spirituality itself in the very process of doing away with religion, and disconnecting ourselves from the very source and fountain of our inspiration in our over enthusiasm to get rid of old forms.

Coming to the plain truth of the matter, Hinduism, that is, unsectarian higher Hinduism, which Sri Aurobindo called the sanātana dharma, can certainly claim to have laid the spiritual foundation for the entire human race, just as Greek civilisation laid the rational foundation of the present Western civilisation. But non-Hindus need not feel jealous about Hinduism because spirituality is not its monopoly, just as the rules of logical thought are not the exclusive property of the Greeks. If science has mainly developed in Europe and America, it does not prevent Indians from becoming world class scientists without having to lose their own culture. So also if India has been the land of spirituality from ancient times, it should not preclude Westerners from practising the spiritual discipline and becoming realised Yogis without having to follow the external rituals of Hinduism. The world moves on, and everybody learns from each other, and nobody makes a big fuss about where you learn from as long as you get the best available resources. It is with this generous and practical attitude that we should go ahead instead of raising unnecessary objections with regard to the superiority or inferiority of other cultures. Indians would certainly be foolish not to modernise themselves with Western education despite the barriers of language and culture they will have to face one day. But it would be equally foolish for Westerners to reject the higher values of Hinduism out of jealousy and chauvinism or even from sheer unfamiliarity, especially when the inner journey has begun. Learning from other cultures in the right spirit, or at least recognising their place in the larger scheme of things should not deprive us of our identity nor our dignity, if that is what we are mostly concerned about in these kinds of cultural disputes!

Notes and References

[i] Though I have made a generalisation I should say there are exceptions such as David Frawley, Konrad Elst, Michel Danino and a few others who have sufficiently steeped themselves in Hinduism in order to recognise its spiritual values. But it is only recently that their voices are being heard with some interest – that too has happened more because of the facility of Internet blogging than by an appreciation of their views by the secular media.

[ii] I know the secular lobby would at once raise objections to this sentence and cry itself hoarse, “What happened in Gujarat? What happened to Mohammad Akhlaq? What about the imposition of Vande Mataram?” But these accusations have been so often repeated in the last few years, and in such a biased manner that they have become more part of electoral politics than occasions for serious cultural introspection. What I am pointing out is the current social situation in which the normally timid Indian with a Hindu background is generally on the back foot, unless he is pushed to the wall and forced to defend himself. In any case, I would give more attention to the larger social picture that emerges than the few communal flare-ups that have been over-emphasised for political gain.

[iii] Peter Heehs, “Sri Aurobindo and Hinduism” (2006) at http://anti-matters.org/articles/123/public/123-180-1-PB.pdf. Read my review on this article at http://www.thelivesofsriaurobindo.com/2010/08/sri-aurobindo-on-hinduism-by-peter.html.

[iv] Letters on Himself and the Ashram, CWSA 35, pp. 76-77. Quoted by Richard Hartz on p. 153 of The Clasp of Civilizations.

[v] This is implied in the argument though Richard does not explicitly say so, or rather he makes Sri Aurobindo say it for him in a decontextualised manner. For if the spiritual value of Sri Aurobindo’s early views on Hinduism is recognised, it becomes difficult to reject it in the long run. One has to accept the full implications of whatever position one takes, instead of denying the conclusions that automatically flow from the premises one states. I remember Peter Heehs telling his critics in a television debate, “You are making me say what I have never said,” but he actually insinuates (instead of saying it outright) and indirectly suggests highly objectionable conclusions from his very presentation of Sri Aurobindo’s life. Hemming and hawing, for example, on whether Sri Aurobindo’s spiritual hallucinations could be a mad man’s delusions would naturally make the reader suspect Sri Aurobindo’s sanity.

[vi] Read the chapter on “The Discovery of the Nation-Soul” in The Human Cycle, CWSA, Vol. 25, pp 35-43

[vii] Peter Heehs obfuscates the issue by describing the religious (or spiritual) nationalism of Sri Aurobindo as “nationalism raised to a religious pitch of intensity” or the “civic religion of nationalism” (see Nationalism, Religion, and Beyond, pp. 201; 30), but what he means is patriotism or nationalism qualified by but not founded on spirituality. If there was one thing that Sri Aurobindo stood for and attempted to establish, it was the spiritual foundation of all the activities of life; so his politics can hardly be considered an exception to this larger aim of his life. Sri Aurobindo wrote in the Bande Mataram on 18 March 1907 that “in the Swadeshi movement for the first time patriotism became a national religion” and “the name of the motherland was invested with divine sacredness”.

[viii] Read the chapter “Indian Polity – 4” in Renaissance of India, CWSA Vol. 20, pp. 425 ff

[ix] Karmayogin, CWSA, Vol. 8, pp. 302-06. Sri Aurobindo objected to the formation of the Hindu Sabha because its motive was to primarily counter the Muslim League, and not because he was against Hinduism. He writes on the same day (6 November, 1909) that his ideal of Indian Nationalism was “largely Hindu in its spirit and traditions” but wide enough “to include the Moslem and his culture and traditions and absorb them into itself.” This article, which is so often quoted to prove that Sri Aurobindo rejected Hinduism, actually shows the wide and inclusive Hinduism that he stood for in the Indian national movement.

[x] The Renaissance of India, CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 25

[xi] Though Richard does not explicitly say so, he implies it in his defence of Sri Aurobindo against the accusation of being anti-Muslim. If Richard accepts the authenticity of the Talks on a case to case basis, his whole defence would collapse.

[xii] Nationalism, Religion, and Beyond (2005) by Peter Heehs, pp. 214-19

[xiii] Autobiographical Notes, CWSA, Vol. 36, p. 94

[xiv] Early Cultural Writings, CWSA Vol. 1, pp 551-52

[xv] Nationalism, Religion, and Beyond (2005) by Peter Heehs, p. 14. Also “Sri Aurobindo and Hinduism” (2006) by the same author.

[xvi] Letters on Himself and the Ashram, CWSA 35, pp 699

[xvii] Ibid, pp 699-700. Also Bulletin, August 2000, pp. 70-72. I have quoted the unabridged Bulletin version of the question to give the full context.

[xviii] Karmayogin, CWSA, Vol. 8, p. 26

[xix] The Renaissance of India, CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 179

[xx] Letters on Himself and the Ashram, CWSA Vol. 35, p. 701

[xxi] Ibid, pp. 700-01; also Bulletin, August 2000, p. 74.

[xxii] Letters on Himself and the Ashram, CWSA Vol. 35, p. 702

[xxiii] Bulletin, August 2000, p. 72. Not in CWSA.

[xxiv] Bulletin, February 2001, p. 72. Also Letters on Himself and the Ashram, CWSA Vol. 35, p. 701.

[xxv] Nationalism, Religion, and Beyond (2005) by Peter Heehs, p. 352. Also “Sri Aurobindo and Hinduism” (2006) by the same author

[xxvi] Peter Heehs, The Lives of Sri Aurobindo, p. 343: “But if Aurobindo was indifferent or opposed to ceremony, Mirra thrived in it. She was happy to see the sadhaks spending hours stringing garlands and preparing special dishes, and later, during the darshan, bowing down at Aurobindo’s feet.”

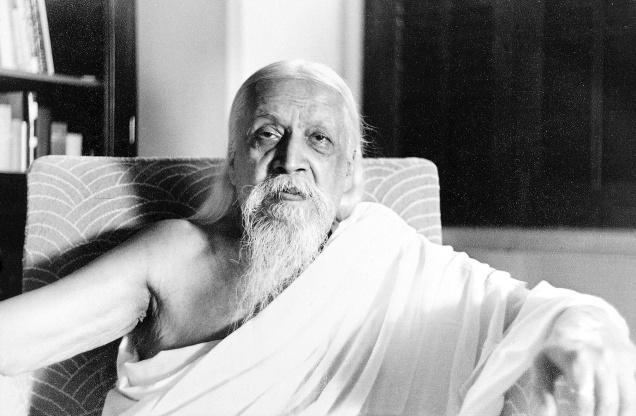

Featured Image: Auroville