A Heritage Temple

Prashant S. Bhardwaj is the head priest of the Veera Narayana Temple, Belavadi. The Veera Narayana Temple is dedicated to Veera Narayana, a form of Lord Vishnu, in the village of Belavadi, Chikamagalur district, Karnataka. The temple was built in the 12th century CE by the Hindu dynasty of the Hoysalas, based at Halebidu which was then called Dwarasamudra. They also built the famous temples at Belur and Halebidu.

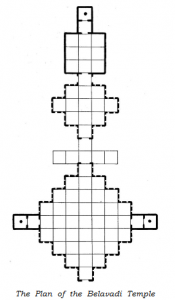

It is not in the scope of this article to discuss the architectural or sculptural beauty of the temple. It would be enough to say that while other more famous Hoysala temples are popular for their sculpture; this temple is famous for its wonderful architecture. It is a trikuta temple, but with a peculiar and novel plan, which separates the two lateral shrines from the original shrine with two mandapams and a lateral open gallery and thus its facade is the most beautiful of all Hoysala temples. It has the largest joint mandapam of any Hoysala temple with 59 bays. There are 108 pillars in the temple and no two are alike. It is this great temple, which has its head priest as Prashant S. Bhardwaj.

An Ancient Community

He belongs to the very rare Vaikhanasa community of temple priests. The Vaikhanasa community are traditional priests in Vaishnava temples who follow the Vaikhanasa Agama. Agamas are the Shastras, which govern the worship rituals in temples. The Vaikhanasa Agama is also called as Bhagavat-Shastra by the Vaikhanasas. The Vaikhansa Agama is said to be the oldest of all Agamas, and the Vaikhanasa community is also said to be the oldest living community of temple priests. Most of them are found in Tamil Nadu and the adjoining areas of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. The famous Venkateshwara temple at Tirupati is run according to Vaikhanasa Agama, by the Vaikhanasa community.

The serenity and calm of the picture-perfect village Belavadi is attractive to a visitor, but for a local youth to devote his entire life to the tradition is not easy, even when the tradition is as glorious as that of the Hindu temple and when the monument and heritage to defend and propagate is as spectacular as the Veera Narayana temple at Belavadi.

A Hard Choice between Tradition and Modernity

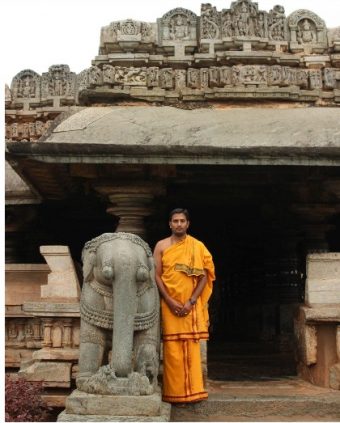

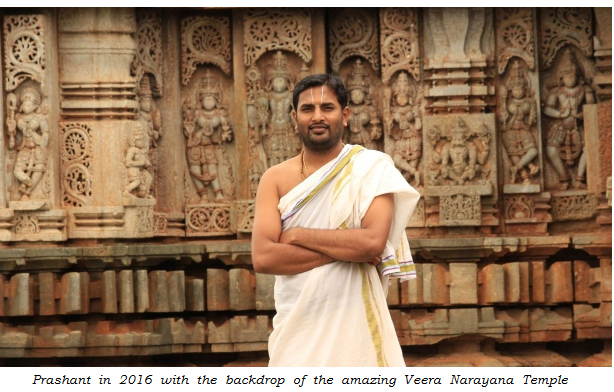

When I interviewed him in a rainy August of 2016, he was exactly my age, 33. The energy, optimism and the hope that comes with youth was on his face. He was wearing the traditional attire of a Vaikhanasa priest: white dhoti and angavastram. He had the Vaishnava tilak on his forehead and he had just arrived after offering worship to the deity. He was entirely reconciled with his role as the head priest of a provincial temple. As far as I could think, any young man in his position would be at best conflicted, forever on the crossroads of the security of tradition and the possibilities of the wider world.

I couldn’t help but ask: what prompted him to become the priest of a temple in a small village, following all the strictures that came with the job, especially when the wider world was open to him?

It must be hard for a youth his age, who is also educated in the modern idiom to abstain from all the ‘pleasures’ of the modern life and to immerse himself in the preservation of tradition for the sake of his family, his clan, his community and his dharma.

It appears, for Prashant, it was not so. Of course, the temptations to take wings and fly away to embrace the wider world were many. Of course, there were attractions of the ‘other’ life; the life which is normal for most of us. But the choice was never hard for Prashant. When it came to choose between upholding the great Vaikhanasa tradition of the Veera Narayana Temple, Belavadi on the one hand and to become a commoner and become ‘normal’ in the modern world on the other, Prashant easily chose his heritage over the rest of the world.

He had never been out of touch with his tradition and heritage and always considered it his first priority. He had completed school education in Belavadi and then took regular education in Bangalore, from where he got his Bachelor of Arts degree. It was after that he chose to take the path of becoming a priest.

Sometimes people rationalize the choices that they have made; often in retrospect. But Prashant’s claim that he always wanted to devote his life to the preservation of his tradition, was not an afterthought. The choice to become the head priest of Veera Narayana temple, Belavadi was deliberate. It was a conscientious decision, which involved a lot of forethought. He knew what he was getting into when he enrolled into the course of Agama Shastra at the Sanskrit Department, University of Mysore.

The course has been made mandatory by the Sringeri Sharada Peetham for anyone who wants to become a priest. And it is Sringeri Sharada Peetham, which takes care of the worship and other rituals in the temple at Belavadi. To become a priest is no longer a hereditary privilege only. One has to earn it.

The fact that Prashant consciously chose to undergo hard training for seven years shows his commitment to uphold his heritage. The seven years course is divided into three parts: 3 years Pravara, 2 years Praveena, 2 years Vidvata. Prashant underwent the entire course and upon graduating, came back to become a priest in 2010.

But there was one last dilemma. Prashant always knew he wanted to become a priest. But the choices are everywhere. Even when he had taken the training to become a priest, the choice for him was: to become the hereditary priest at Belavadi, or to take up the priesthood in a temple abroad. He was getting offers from many temples in US, UK and Australia from 2009, even before he had completed his Agama education in Mysore. One Lakshmi temple, London, had offered him a salary of one lakh and fifty thousand rupees per month.

The offer was very lucrative. He was to get a very comfortable salary, compatible with any free market job these days and he got to ‘live the life’ abroad. The other option was the hereditary priesthood at Belavadi. Sure, there was heritage. Of course the temple was ancient and the heritage was worth preserving. But the hardships were many.

Choosing Belavadi would mean choosing the provincial way of life for the rest of his life and also for his family. The salary, which the Sringeri Sharada Peetham paid was very meagre: only two thousand rupees per month. Apart from this salary and the meagre donations that the temple received he had nothing to go by as the head priest at Belavadi is forbidden to take up any other job.

Choosing Belavadi meant taking up a life of extreme discipline and restraint. Hindu Shastras forbid the Brahmins and the priests especially to cross the ocean. Once Prashant chose to stay at Belavadi, the wider world across the ocean would be closed to him forever. On the other hand, if he crossed the ocean once, the gates of Belavadi will close for him forever. And only someone from the Vaikhanasa family can become a priest at Belavadi. On the other hand, anyone could become the priest at Lakshmi temple, London. It was a hard choice.

Choosing Belavadi meant his family would have a hard time finding a bride for him. The Vaikhanasa community is a very small one and finding girls for marriage is a daunting task. For someone living in a village like Belavadi, it is even harder. As Prashant’s family is the only Vaikhanasa family in the village, they would have to seek elsewhere. But Prashant says that almost no girl wants to come down and settle in a village. He told the story of a nearby village in which there were forty unmarried young men of age. His own village has around fifteen Brahmin youth who are of age and still unmarried. There was a great possibility that if he chose Belavadi, he would never get married.

Prashant chose to go abroad and take up the job in London. Anyone would have. He started preparing for the journey across the ocean. He even had his passport ready. But somewhere in his heart, he felt that he was making the wrong choice. Even after he had decided to go abroad, the charm of Belavadi would not leave him. He had never been so conflicted. Just before he was about to leave, he went to a Jyotisha to whom he often used to go when in conflict. The Jyotisha advised him to stay. Prashant was elated! The Jyotisha had spoken what was already in the heart of Prashant. Somewhere deep in his heart, he knew he was never going to leave Belavadi.

The Call of the Road

Seven years later, in 2016, he was confidently doing his duties at the Veera Narayana temple, when I interviewed him. Elaborate Shodasha Upachara worship is offered at all the three temples twice a day by him. There are various monthly, yearly and other festivals: Abhishekams, Kumbahbhishekam, Brahmotsavam, etc. Rath Yatra is taken on many of these festivals. The humble complexity of a dharmic life cantered at the temple has him completely engrossed.

Even then Prashant has the travel bug. While I was asking all the questions, he would interject in between and enquire about my travels and congratulate me again and again on my luck that I get to travel so much. I couldn’t help but ask: how does he manage his desire for travel and seeing the world, while being the priest at Belavadi?

It is hard, agrees Prashant, as the call of the road is almost irresistible for him sometimes. The duties of being the head priest do not let him leave the temple for most of the time. But once every year, for fifteen days, at a stretch, Prashant lets loose his inner traveller. He goes travelling the length and breadth of India, seeing the great temples and heritage places. For this interval, his cousin from Bangalore performs the duties at the temple.

In his modern clothes, he doesn’t betray his priestly background while travelling. He always keeps his vow and abstains from every kind of food prohibited to a priest. This is how he balances his duties and his passion. By letting out his travelling demon once every year for 15 days, he keeps it within check so that he can devote the rest of his year to his priestly duties.

Almost nine years ago, Prashant chose to reject the world and chose Belavadi. But much to his amusement, the world came to him. For the Veera Narayana temple is an architectural gem. In the words of Gerard Foekema, the temple has “the most majestic temple front in all Hoysala architecture”. [1]

The larger hall (mandapam) is so majestic that it is seldom matched. Though there are other trikuta Hoysala and Chalukya temples in Karnataka and elsewhere, but no other trikuta temple has the peculiar architecture of Belavadi, where the oldest shrine is separated from the other two lateral shrines by not one or two, but three mandapams.

Compared to the temples at Belur and Halebidu, the one at Belavadi is not that famous, but the age of social media is gradually giving the Veera Narayana temple the place that is due to it. People from all over the world; especially the temple enthusiasts and scholars who are devoted to the preservation of the Hindu heritage keep coming to this temple and keep exploring it; bringing the world to Prashant.

The temple is a great magnet for scholars, authors, journalists, saints, Hindu activists and temple enthusiasts. He rattles off a few names with a proud smile on his face: Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, temple scholars like Gerard Foekema and Adam Hardy and Hindu activists like Shefali Vaidya. For fifteen days every year, Prashant leaves Belavadi to see the world. For the rest of the year, the world itself comes to Belavadi, at the very doorstep of Prashant, the head priest of Belavadi.

And Prashant did get lucky in marriage. Just like he chose to defend heritage instead of chasing a lucrative financial career, Shweta, a girl from Bangalore, instead of choosing a ‘happening’ city life, chose to marry him and come to Belavadi to spend the rest of her life with him.

Conclusion

Prashant’s story is fascinating, inspiring and uplifting. But it is not one-of-a-kind. He is not the first to make the choices that he did. Many before him have made similar choices, many like his father, like his community. For ages, Brahmin families have been living by the dharmic code and devoting their lives for the preservation of heritage and culture. For centuries, individuals like him have been making the right choice and have been sacrificing their desires in order to carry on the knowledge tradition.

For when the Islamic invaders arrived in India and laid waste to our universities, libraries and other educational institutions, it was these ‘orthodox’, ‘discriminating’, ‘elite bookworms’ who preserved Hindu knowledge orally and transmitted it from generation to generation at great personal risk.

They have been much maligned for their ‘rigidity’, ‘caste orthodoxy’ and ‘hereditary privilege’, but it was precisely because they maintained these hereditary structures that they could preserve Indian knowledge traditions for posterity.

In a world where rights are more important than duties; individuals are more important than desh or dharma; activism is more important than knowledge; and where this activism is reduced to nothing more than the fight for the most basic of human desires, the code by which the Brahmins used to live is ridiculed and left to fade away.

Though Brahmins are migrating to different pastures and not doing so bad, as individuals, the Brahmana way of life is headed for extinction. Everything that a Brahmin held dear to his way of life has been so thoroughly abused and maligned by Marxist, left-liberal and secular intellectuals that no one dares own them up in public any longer.

What is at stake here is not a particular community, but the dharmic code of life. Brahmins will survive one way or the other. What is in danger of going extinct is the knowledge tradition of India; the Brahmana way of life. Prashant S. Bhardwaj, the head priest of Veera Narayana Temple, Belavadi chose to ignore the abuses and the ridicule of the world, and went on to preserve his tradition and heritage. But if the conditions remain the same, if India continues to remain apathetic to its glorious knowledge tradition, not many will choose to do the same in future.

Notes and References

- Foekema, Gerard. Hoysala Architecture: Medieval Temples of Southern Karnataka Built During Hoysala Rule (2 Vol). New Delhi: Aryan Books, 2014. p. 108.

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness,suitability,or validity of any information in this article.

Pankaj Saxena is a scholar of History, Hindu Architecture and Literature. He has visited more than 400 sites of ancient Hindu temples and photographed the evidence. He has been writing articles, research papers and reviews in various print and online newspapers and magazines. He currently works as the Asst. Professor, Centre for Indic Studies, Indus University, Ahmedabad. He has authored three books so far. He maintains a blog at http://literaryfalcon.wordpress.com/