During the Second World War, when the plague of Nazism was consuming Europe crushing all forms of dissent or opposition against it, the Vatican committed itself to a policy of conciliation and church diplomacy in the inter-war period. This helped the Vatican to sustain an environment in which the church could function as freely as possible.

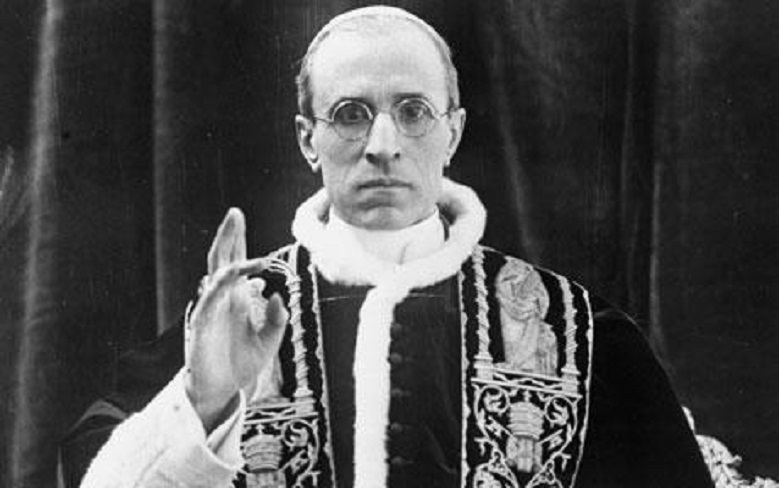

Historians generally agree, after going through evidence, that Pope Pius XII (1876-1958) who headed the Vatican during those tumultuous times remained silent even as the Nazis went about committing grave and atrocities with impunity. The Vatican defended this act of indifference was defended on the grounds of neutrality.

Many of the Vatican’s defenders claim that Eugenio Pacelli, (birth name of Pope Pius XII) demonstrated a deep commitment to the spiritual mission of the Holy See and thus saw his role as avoiding association with power blocs. As a result, when fascism extended its influence in Europe during those dreaded times, the Vatican remained detached, occasionally challenging fascist ideology when it touched on important matters of Catholic doctrine or the legal position of the church, but unwilling to interfere with matters it considered to be purely earthly—like mass killings of innocents.

This is because at some stage, the Vatican found many facets of fascist regimes affable, such as their symbolic patronage of the church, their challenge to Marxism, and their repeated backing of a conservative social vision.One interesting part about Pope Pius XII is that he resided in Germany from 1917, when he was appointed the Papal Nuncio (diplomatic representative of the Vatican) in Bavaria, until 1929. So he was perfectly well-aware what Nazism stood for. So how did he react when Hitler took power in 1933?

On 20 July that year, the future Pope, and Hitler’s representative Franz Von Papen signed a concordat that granted freedom to the functioning of the Roman Catholic Church. In return, the Church agreed to separate religion from politics. This concordat is generally viewed by historians as a diplomatic victory for Hitler since it gave the Third Reich a significant form of legitimacy.

Between that period and the time when he was elected Pope in 1939, Pacelli did show his political shrewdness by portraying himself as a critic of the Reich which can be seen in this speech he gave to pilgrims at Lourdes on 28 April 1935 regarding the Nazis:

It does not make any difference whether they flock to the banners of the social revolution, whether they are guided by a false conception of the world and of life, or whether they are possessed by the superstition of a race and blood cult..

Now after he was made the chief of state of the Vatican, Pope Pius XII was also the Bishop of Rome which meant in theory that his views could influence millions of Catholics who resided in Europe. Thus, as noted in the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust Summi Pontificatus, the first encyclical (which is like a letter) of his pontificate, issued on 20 October 1939, the doctrines of totalitarianism, racism, and materialism were attacked but that was more like a tactical move.

However, the Vicar of Christ did not find the Kristallnacht (the night of broken glass) which occurred in November 1938, racist enough to condemn. This in face of the fact that Jewish residents were brutalised by the Nazis openly. On the bright side, he did obtain visas to enter Brazil, for those European Jews who had been baptized and converted to Catholicism.

Sadly, two-thirds of these visas were later revoked, probably because the Jews started practicing Judaism once in Brazil. At that time, the Pope did nothing to save practicing Jews. That is accordance to the Vatican’s stand: Jews are fine as long as they do not follow Judaism.

If one goes through the voluminous Encyclopedia of the Holocaust andPerpetrators Victims Bystanders, several disturbing examples of the Vatican’s indifference towards the tragic plight of the Jews will become clear:

i. In early 1940, the Chief Rabbi of Palestine, Isaac Herzog, asked the papal Secretary of State to intervene in keeping the Jews in Spain from being deported to Germany. The papacy stayed quiet.

ii. In 1942, the Slovakian charge d’affaires, a position under the regulation of the Pope, reported that Slovakian Jews were being systematically deported and sent to death camps. Still, no sound of opposition from the Pope.

iii. In October 1941, the Assistant Chief of the U.S. delegation to the Vatican, Harold Tittman, asked the Pope to condemn the atrocities. Tittman was told that the Holy See felt that condemning the atrocities can harm the Catholics in German-held lands (assuming he included the Nazi leaders Goebbels and Himmler who were Catholics as well).

iv. On September 1942, when Myron Taylor, U.S. representative to the Vatican, warned the Pope that his silence was jeopardizing his moral standing, the reply was that it’s difficult to authenticate rumours about crimes committed against the Jews.

The one incident where the Pope was seen to act was during the German occupation of Hungary in March 1944, after papal nuncio in Budapest, Angelo Rotta, pleaded with the Holy See while advising the Hungarian government to be moderate in its treatment of the Jews. Rotta’s pleas succeeded as Pius XII tirelessly protested against the deportation of Jews.

However, Martin Gilbert in his book The Holocaust opines that similar protests from the King of Sweden, the International Red Cross, Britain and the United States, which, combined with the Pope’s demands, contributed to the decision by the Hungarian regent, Admiral Miklos Horthy, to cease deportations in July 1944. Martin in the same book does credit the Pope for instructing Catholic institutions to take in Jews. The Vatican itself sheltered about five hundred Jews and above four thousand Jews were protected in Roman monasteries and convents.

But the reason for the Pope’s new-found love for Jews was after 1942, when U.S. officials told him that the allies were preparing for total victory, and it became likely that they would get it. Historians point to the fact that in late 1942, Pius XII began to advise the German and Hungarian bishopsthat it would be to their ultimate political advantage to go on record as speaking out against the massacre of the Jews.(From page 136 ofHolocaust published by the Israel Pocket Library.)

This is proven also by the fact that just a year earlier, in 1941, when the Vichy French government legislated ‘Jewish laws’ which closely followed the anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws, the same Pope responded by stating that such laws were not in conflict with Catholic teaching so long as they don’t undercut Church authority or involve occasional breaches of “justice and charity”.

One line of defence by the Vatican’s apologists without giving any evidence is that well-known efforts by many Catholic institutions to help the Jews were actually orchestrated by the Pope. Now there were indeed occasions when brave Catholic clergymen as well as laymen helped the Jewish victims to escape Nazi authorities at great personal risk. But to credit the Vatican for these great souls without proper proof is equal to condemning all Germans as Nazis.

The best the Pope himself did was encourage humanitarian aid by subordinates within the Church—indirectly—and issued vague appeals against the oppression of unnamed racial and religious groups whatever that meant.

In the present, some historians have come to appreciate the tactical silence of the Vatican. One such historian, Günther Lewy, stated that condemnation by the Pope against the Nazis would almost certainly have botched to move the German public and would likely have made matters worse for the half-Jews as well as for practicing Catholics in Germany. And most scholars claim that much of the Vatican’s actions are in line with most of the then-Europe which saw Nazism as a bulwark against the spread of Marxist ideology.

If that is the case, then why do we bother calling the Vatican ‘Holy?’ I can understand Pope’s astute diplomacy, but I cannot call a man ‘Holy’ who sat silent like the fabled story of Nero when Rome burned.